The Social History of Quilt Making in America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 2018

YMOCT18Cover.FINAL:Layout 1 11/1/18 5:21 PM Page CV1 CAN YOU KEEP BE THE LISTEN A SECRET? CHANGE UP! Protect shared The retail Podcasts get you information with landscape is inside the heads of a nondisclosure changing your customers— agreement. quickly.Are literally. you ready? OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2018 2019: A YARN ODYSSEY FREE COPY DelicatE wslavender eucalyptus grapefruit unscented jasmine h p teatmen o you in ashable YMN1018_Eucalan_AD.indd 1 10/23/18 12:49 PM Plymouth Yarn Pattern #3272 Drape Front Cardi Plymouth Yarn Pattern #3272 Drape Front Cardi 60% Baby Alpaca 25% Extrafine Merino 15% Yak 60% Baby Alpaca 25% Extrafine Merino 15% Yak WWW.PLYMOUTHYARN.COMWWW.PLYMOUTHYARN.COM YMN1018_Plymouth_AD.indd 1 10/23/18 12:48 PM YMOCT18EdLetter.FINAL:Layout 1 10/31/18 2:24 PM Page 2 EDITOR’S LETTER Looking Back, Looking Forward ROSE CALLAHAN Where were you five years ago? It was the fall of 2013. Some of you may not have even owned your business in the yarn industry yet, while others of you had been at it for well over 20 years. Some of you had not yet become parents; others were close to becoming empty nesters. A lot can change in five years, but of course, a lot can stay the same. Five years ago, Yarn Market News made a change. Because of dwindling advertising dollars, we announced that we would be publishing three issues a year instead of five. And this issue marks our first all-digital issue, born out of both a desire to go green and to help the magazine’s struggling bottom line. -

Mead Library Listing As of December 2019 MEAD QUILTERS LIBRARY Page 2 of 14

MEAD QUILTERS LIBRARY Page 1 of 14 Surname Forename Title Publisher ISBN Date Adams Pauline Quiltmaking Made Easy Little Hills Press 1-86315-010-2 1990 Alderman Betty Precious Sunbonnet Quilts American Quilters Society 978-1-57432-951-3 2008 Alexander Karla Stack A New Deck Martindale 1-56477-537-2 Anderson Charlotte Warr Faces & Places C & T Publishing 1-57120-000-2 1995 Anderson F. Crewel Embroidery Octopus Books Ltd. 0-7064-0319-3 1974 Asher & Shirley & Beginner's Guide To Feltmaking Search Press 1-84448-004-6 2006 Bateman Jane Austin Mary Leman American Quilts Primedia Publications 1999 Baird Liliana The Liberty Home Contemporary Books 0-80922-988-9 1997 Balchin Judy Greetings Cards to Make & Treasure Search Press 978-1-84448-394-5 2010 Bannister & Barbara & The United States Patchwork Pattern Book Dover Publications Ltd. 0-486-23243-3 1976 Ford Edna Barnes Christine Colour- the Quilters Guide That Patchwork Place 1-56477-164-4 1997 Bell Louise 201 Quilt Blocks, Motifs, Projects & Ideas Cico Books London 0-19069-488-1 2008 Berg & Alice & Little Quilts All Through The House That Patchwork Place 1-56477-033-8 1993 Von Holt Mary Ellen Berlyn Ineke Landscape in Contemporary Quilts Batsford 0-7134-8974-X 2006 Berlyn Ineke Sketchbooks & Journal Quilts Ineke Berlyn 2009 Besley Angela Rose Windows for Quilters Guild of Master Craftsman 1-86108-163-4 2000 Bishop & Robert & Amish Quilts Laurence King 1-85669-012-1 1976 Safandia Elizabeth Bonesteel Georgia Lap Quilting Oxmoor House Inc. 0-8487-0524-6 1982 Mead Library Listing as of December 2019 MEAD QUILTERS LIBRARY Page 2 of 14 Surname Forename Title Publisher ISBN Date Bonesteel Georgia Bright Ideas for Lap Quilting Oxmoor House Inc. -

Patchwork and Quilting Holidays - 2021 Project Choices & Kit List

Patchwork and Quilting Holidays - 2021 Project Choices & Kit List Project Choices: Samplers, Seminole, Beautiful Bargello & Delectable Mountain For 2021 we are going to continue our exploration of all things sampler and stripy, as well as offering the lovely Delectable Mountain! Sampler Blocks and the new Seminole Sampler Patchwork (where the patchwork patterns are worked in rows rather than blocks) are fun and very versatile and great for learning lots of new patchwork techniques. Choose from a wide range of designs to make useful and beautiful items. Beautiful Bargello projects will still be available, plus Clare‘s new Modern Art Bargello designs - one using wonderful batik landscape fabric for a quick and easy `cheats‘ Bargello and the other a pictoral quilt with a flexible Bargello section within it. New for 2021 are several variations of the traditional design - 'Delectable Mountain'! This is a lovely design with a modern feel if made with just two contrasting plain fabrics - or it is an ideal scrap buster or layer cake project for a very different look. Once the blocks are made (with Clare’s favourite ‘speedy’ method) there are many different ways they can be used, so lots to play with! Christmas 2021 - Join us for a festive Christmas Patchwork Weekend! Make a quick Christmas quilt, wall hanging, table runner, placemats, coasters, or bunting; lovely for your home or to give as gifts. We’ll be focusing on quick techniques and projects in time for Christmas! Guests will as ever be very welcome to bring along their own projects to work on. Our patchwork and quilting holidays offer a great opportunity to finish those UFOs (Unfinished Objects) or WIPs (Works In Progress) - with the luxury of time, space and expert advice on hand if needed – you can finally see those projects completed! If you have a kit you've started and gotten stuck - or been unable to start at all - do bring it along and we'll get things moving. -

Anniescraftstore.Com AWB9

QUILTING | FABRIC | SEWING NOTIONS | CROCHET | KNITTING page 2 page 4 page 2 page 30 page 11 FEBRUARY 2019 AnniesCraftStore.com AWB9 CrochetCraft & Craft Store Catalog inside 2–40 Quilt Patterns & Fabric 41–57 Quilt & Sew Supplies 58–61 Knit 62–83 Crochet Rocky Mountain Table Runner Pattern Use your favorite fabrics to make this runner truly unique! You can use 2½" strips or fat eighths to make this table runner. skill level key Finished size: 15" x 46". Skill Level: Easy Beginner: For first-time 421824 $6.49 stitchers. Easy: Projects using basic stitches. Intermediate: Projects with a variety of stitches and mid-level shaping. Experienced: Projects using advanced techniques and stitches. our guarantee If you are not completely satisfied with your purchase, you may return it, no questions asked, for a full and prompt refund. Exclusively Annie's NEW! Poppy Fields Quilt Pattern This design is composed of basic units that, when combined, rotated and infused with bold and beautiful fabrics, create a sparkling masterpiece. Finished size is 63" x 63". Skill Level: Intermediate Y886416 Print $8.99 A886416 Download $7.99 2 Connect with us on Facebook.com NEW! Owl You Need is Love Quilted Quilt Pattern Owls are all the rage, regardless of the time of year. With These little fellas are meant for Valentine’s Day— Love! or for any other day you choose to display them! Finished size: 40" x 52". Skill Level: Intermediate RAQ1751 $12.49 (Download only) Exclusively Annie’s NEW! Rustic Romance Quilt Pattern These pieced blocks NEW! Have a Heart Quilt Pattern at first glance give Use your favorite color to make this lovely the appearance quilt. -

Free Motion Quilting by Joanna Marsh of Kustom Kwilts and Designs

Tips and Tools of the Trade for Successful Free Motion Quilting By Joanna Marsh of Kustom Kwilts and Designs Are you looking to add some “pizzazz” to your pieced quilting projects? The quilting on a project can add drama and really make a statement in what might otherwise be an ordinary quilt. Let’s take a look at the basic steps to getting started on your journey into free motion quilting! Supplies you’ll want to invest in (or at least research): • Free motion foot-compatible to your machine • Quality machine quilting thread • Scrap batting (no smaller than 10” x 10”) • Scrap fabrics (no smaller than 10” x 10”) • Spray baste or safety pins • Sketchbook and pens/pencils • Quilting needles • Disappearing ink pen (optional) • Seam ripper • Supreme slider by Pat LaPierre (smaller size) • Stencils • Chalk pounce pad • Chalk for pounce pad • Various rulers for quilting (1/4” thick) • Ruler foot (if applicable) Tools of the Trade: Drawbacks and Benefits Tool Benefit Drawback Spray Baste Fast and more convenient than safety pins. Can gum up your needles. It needs to be More repositionable. sprayed outside. Disappearing Ink Pen Great for marking. The pens that disappear with heat can reappear in extreme cold. Pens that are “air” soluble will have markings that won’t last long the more humid the air is, but can reappear after washing. Quilting Gloves Provide you with an extra grip for easier Personal preference - they can be hot. movement of quilt sandwich. Supreme Slider Allows for super easy movement of quilt layers, Can be expensive. Needs to be replaced over especially helpful on domestic machines/sit time and use and has to be kept clean. -

Summer Ta Y Bolster Pillow Skill Level: Intermediate

Summer Tay Bolster Pillow Skill Level: Intermediate Designed and Sewn By Susie Layman www.threadsonmysocks.blogspot.com Summer Taffy Bolster Pillows are easy to sew on your machine and one can easily be made in a day. They look great when grouped with pillows of other shapes and sizes and are perfect for a girl’s room or perched on your favorite chairs. Instructions are provided for both ruffled and pleated ends. Finished size - 16” x 4”. Fabrics Needed Fabric A 1 fat quarter Fabric B 1 fat eighth Fabric C* ¼ yard straight cut Fabric D* ¼ yard straight cut *Fabric C can be used for both the inside and outside of the rue or pleat at the end of the pillow. If so, eliminate fabric D and replace with ⁄ yard of fabric C. Materials Needed Pellon® 987F Fusible Fleece ½ yard Pellon® Perfect Loft® Cluster Fiber Fill 1 bag Thread Tools Needed Sewing machine and related supplies Rotary cutter and related supplies www.pellonprojects.com Graphic Artist Alexandra Henry PERMISSION IS GIVEN TO REPRODUCE FOR PERSONAL USE ONLY ©2014 - PCP Group, LLC www.pellonprojects.com Assembly Seam allowance is ½” unless otherwise noted. Step 1. Cutting Instructions. Fabric A Cut one 17” x 16” rectangle for outer pillow body Fabric B Cut two 5” circles using the template found on page 3 Fabric C Cut two 3” x width of fabric strips for outer rue/pleat* Fabric D Cut two 3” x width of fabric strips for inside rue/pleat* Fusible Fleece Cut one 16” x 15” rectangle Cut two 5” circles using the template found on page 3 *If fabric C is used for inside and outer rue, eliminate the cut for fabric D and cut two 5” x width of fabric from fabric C. -

History of Quilting

History of Quilting When the first settlers came to this country they brought with them their quilting skills. New fabric was hard to come by, so fabric for clothing and for quilts had to be used and reused saving as much as possible from worn clothing. Thus the patchwork quilt was born. Scraps of fabric were cut into geometric patterns that fit together into larger blocks of design. Many of these patterns have been passed through generations, created by the ingenuity of our ancestors and traded within communities. Names for particular patterns sometimes changed as they moved from one part of the country to another, reflecting the environment within which it was named. (i.e. a pattern called the pine tree pattern in Connecticut might be named bear’s path in Ohio). Quilt making is an art form that both individuals, as well as groups of people participated in. From the lore surrounding quilt making we learn that parents passed the skills for quilt making on to their children at a very young age. The children would start with small patches of fabric, and learn to sew the very fine stitches needed for beautiful and elaborate quilts. Historically, quilting has generally been practiced by, and associated with women. This could be because the sewing skills needed to make a quilt have always been an integral part of women’s lives. Learning how to sew was such an important skill for girls to have that it was taught and practiced in the home and at school. Women of all classes participated in this form of expression. -

Free Project Sheet

{ FEATURING UTOPIA COLLECTION} FREE PROJECT SHEET DESIGNED BY : QUILT DESIGNED BY FRANCES NEWCOMBE KIT QUANTITY UT-24502 1/8 yd. UT-24509 1/4 yd. UT-24507 1/4 yd. UT-24204 1/8 yd. FINISHED SIZE: 42" X 42" UT-14501 1/8 yd. To download the instructions UT-14505 1/4 yd. UT-14503 1/4 yd. for this pattern visit UT-24506 3/8 yd. NE-104 1 yd. artgalleryfabrics.com Backing 1 1/2 yd. by UT-14500 UT-14501 UT-14502 UT-14503 UT-14504 Dreamlandia Atomic Influx Perse Specks of Rambutan Megalopolitan Dim Orni Bioluminescence Illuminated FANTASY CITY FERVOR UT-14505 UT-14506 UT-14507 UT-14508 UT-14509 Chatter Pods Citrica Lucid Hills Amber Paradise Dwellers Vivid Urban Sprawl Magenta Aglow Sapling Mango UT-24500 UT-24501 UT-24502 UT-24503 UT-24504 Dreamlandia Atomic Influx Alloy Specks of Carambola Megalopolitan Glim Orni Incandescence Irradiated REVERIE CITY WINTER UT-24505 UT-24506 UT-24507 UT-24508 UT-24509 Chatter Pods Menta Lucid Hills Jade Paradise Dwellers Urban Sprawl Grass Aglow Sapling Sloe Neon © 2014 Courtesy of Art Gallery Quilts LLC. All Rights Reserved. 3804 N 29th Ave. Hollywood, FL 33020 PH: 888.420.5399 FX: 425.799.6103 FABRICS DESIGNED BY FRANCES NEWCOMBE FOR ART GALLERY FABRICS QUILT DESIGNED BY Karen Turchan CUTTING DIRECTIONS FINISHED SIZE: 42" X 42" ¼" seam allowances are included. WOF means width To download the instructions of fabric. for this pattern visit One (1) 3 1/2" x WOF strip from fabric A Sub cut strip into four (4) 3 1/2" X 6 1/2" strips artgalleryfabrics.com Two (2) 3 1/2" x WOF strips from fabric B Sub cut strip into four (4) 3 1/2" x 12 1/2" strips Two (2) 3 1/2" x WOF strips from fabric C Sub cut strip into four (4) 3 1/2" x 18 1/2" strips FABRIC REQUIREMENTS One (1) 3 1/2" x WOF strip from fabric D Sub cut strip into six (6) 3 1/2" squares Fabric A UT-24502 1/8 yd. -

VQF Modern Broderie Perse Supply List

Modern Broderie Perse Maria Shell www.mariashell.com www.talesofastitcher.com [email protected] Supply List • Assortment of 10-12 pieces of fabric that measure about 18” by 8”. Smaller or larger is fine, but I like the 18” by 8” because it is the size of a fat eight and because it works well with the size of the Wonder-Under fusible. Please read the below comments about selecting fabric. • A quality pair of small scissors. I like the five inch size for this kind of work. • 3-4 pastel or light print fat quarters for your background choices. • 3-4 darker prints for the “table cloth” fabric. • 3 yards of Wonder-Under or your favorite heat activated fusible. • Pressing sheet • Sewing Machine with 1/4” foot, walking foot, and quilting (hopping/darning) foot • Generous fat quarter for quilt back (at least 18” by 22”) • Generous fat quarter of batting (at least 18” by 22”) Fabric When making a Modern Broderie Perse floral bouquet, I have found that there are several types of prints that work really well. Here are some suggestions- • Bold Geometrics, for example, circles, stripes, plaids, zigzags in HIGH contrast col- ors. You should be able to read the print from far away. • Fabrics that read as solids • Fabrics that have prints you can easily use as guidelines for cutting • Two color prints preferably without black and white. For example, a pink and black fabric is good, but a pink and blue fabric would be more interesting. • Black and White prints of all sorts. Sharing Fabric If we all bring in 10 scraps of fabric that are approximately 5” by 18” or smaller to share we will have plenty of fabric to share with each other. -

Martha's Quilt

MARTHA’S QUILT Jennifer Brett Roxborogh Martha’s Quilt The history of a Broderie Perse quilt made in Armagh, Ireland in 1795 and the people who have been its guardians. Part One The Family In 1881, a young woman of 27 boarded a ship in Belfast and set sail for New Zealand to marry her fiancé George Hill Willson Mackisack. In her trousseau she had a broderie perse quilt made for her grandmother at her marriage in1795. Both grandmother and granddaughter were named Martha Alicia Brett. The Martha Alicia Brett who migrated to New Zealand was my great grandmother. Martha’s grandmother, Martha (or Matilda) Alicia Black, was born into an Armagh Church of Ireland merchant family in1765 and in December 1795 she married Charles Brett of Belfast. The Black family were well established and although Martha’s father’s first name is not known, her mother’s name was Ann. Martha had two sisters, Maria and Elizabeth and there may have been another sister, Catherine. 1 In 1795, Charles Brett (b. 1752) descended from a family of possibly Anglo-Norman settlers who had been in Ireland from at least the 16 th century, was also Church of Ireland. He was a successful merchant and had recently built a comfortable house named Charleville in Castlereagh on the outskirts of Belfast 2. In November 1795, his mother, Molly, died but three weeks later he was celebrating his marriage to Martha Black. Charles was 43 and Martha 30. 3 An established businessman, Charles had been taking care of his widowed mother since his father died in 1878. -

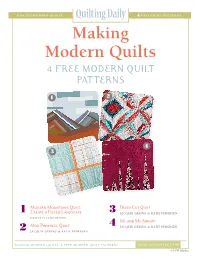

Making Modern Quilts: 4 Free Modern Quilt Patterns Quiltingdaily.Com 1 ©F+W Media Making Modern Quilts Quilting Daily 4 Free Quilt Patterns

MaKING MODERN QUILTS Quilting Daily 4 FREE QUILT PATTERNS Making Modern Quilts 4 FREE MODERN QUILT PATTERNS 1 2 4 3 Modern Mountains Quilt: Fresh Cut Quilt 1 Create a Pieced Landscape 3 JACQUIE GERING & KATIE PEDERSEN KRISTA FLECKENSTEIN Me and My Arrow Mod Pinwheel Quilt 4 JACQUIE GERING & KATIE PEDERSEN 2 JACQUIE GERING & KATIE PEDERSEN MAKING MODERN QUILTS: 4 FREE MODERN QUILT PATTERNS QUILTINGDAILY.COM 1 ©F+W Media MaKING MODERN QUILTS Quilting Daily 4 FREE QUILT PATTERNS hat is modern quilting? There’s no shows you how to cut strip-pieced Wset definition. Typically, though, blocks at wonky angles to give the modern quilts have large fields of solid mountains a bold, contemporary look. colors, take an improvisational approach The Mod Pinwheel Quilt takes the MAKING MODERN to cutting and piecing, and highlight whimsical pinwheel block and gives QUILTS contemporary commercial fabrics. it a modern patchwork twist using 4 FREE One thing’s for certain: foundation piecing. MODERN QUILT modern patchwork In the Fresh Cut Quilt pattern, you'll PATTERNS quilts sure are popular. learn the slice-and-insert technique In Making Modern where three large modern quilt blocks EDITOR Vivika Hansen DeNegre Quilts: 4 Free Modern alternate with solid blocks. ONLINE EDITOR Cate Coulacos Prato Quilt Patterns, The Me and My Arrow modern quilt CREATIVE SERVICES we’ve put together pattern makes a point about points: the DIVISION ART DIRECTOR Larissa Davis three modern quilt pieces and even the quilting have points! designs from the authors of the Quilting PHOTOGRAphERS Larry Stein With these four modern quilt tutorials Modern book, Jacquie Gering and Katie you will learn how to how to capture the Projects and information are for inspira- Pedersen, and one modern landscape flavor of modern quilting in your studio. -

Hexi Pillow Featuring Hindsight by Anna Maria Use Your English Paper Piecing Skills to Create This Beautiful Bolster Pillow in an Assortment of Fun Prints

Hexi Pillow Featuring Hindsight by Anna Maria Use your English Paper Piecing skills to create this beautiful bolster pillow in an assortment of fun prints. Collection: Hindsight by Anna Maria Technique: English Paper Piecing Skill Level: Confident Beginner Finished Size: 6" x 14" (15.24cm x 35.56cm) All possible care has been taken to assure the accuracy of this pattern. We are not responsible for printing errors or the manner in which individual work varies. Please read the instructions carefully before starting this project. If kitting it is recommended a sample is made to confirm accuracy. freespiritfabrics.com 1 of 2 Hexi Pillow Project designed by Liza Prior Lucy Instructions 9. Remove the basting and the papers from all Tech edited by Linda Turner Griepentrog 1 the hexagons. Seam allowances are ⁄2" (1.27cm). 10. Shape the hexagon piece into a tube and Fabric Requirements 1. Sew a line of basting stitches along the whipstitch the adjacent piece edges together. seamline on both 19" (48.26cm) edges of 11. Slip the hexagon tube over the bolster pillow, • Quilter’s Lace from Wheelhouse Medallion the pillow rectangle, leaving the thread ends center and hand-stitch the hexie points to Quilt*, for hexies long enough to pull. the pillow cover. 1 • ⁄4 yard (22.86cm) fabric, for pillow ends 2. With right sides together, fold the pillow 1 • ⁄2 yard (45.72cm) fabric, for pillow fabric rectangle in half aligning the 15" (38.10cm) edges. Sew the seam, leaving a 5" *Quilter’s Lace is leftover fabric once you’ve fussy- (12.70cm) opening in the middle of the seam cut the Wheelhouse Medallion Quilt blocks.