History of Quilting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Naturalistic Study of the History of Mormon Quilts and Their Influence on Today's Quilters

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1996 A Naturalistic Study of the History of Mormon Quilts and Their Influence on odat y's Quilters Helen-Louise Hancey Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Art and Design Commons, Art Practice Commons, History Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Hancey, Helen-Louise, "A Naturalistic Study of the History of Mormon Quilts and Their Influence on odat y's Quilters" (1996). Theses and Dissertations. 4748. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4748 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A naturalistic STUDY OF THE HISTORY OF MORMON QUILTS AND THEIR INFLUENCE ON TODAYS QUILTERS A thesis presented to the department of family sciences brigham young university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree master of science helen louise hancey 1996 by helen louise hancey december 1996 this thesis by helen louise hancey is accepted in its present form by the department of family sciences of brigham young university as satisfying the thesis requirement for the degree of master of science LL uj marinymaxinynaxinfinylewislew17JLJrowley commteecommateeComm teee e chairmanChairman cc william A wilson committee member T -

Summer Ta Y Bolster Pillow Skill Level: Intermediate

Summer Tay Bolster Pillow Skill Level: Intermediate Designed and Sewn By Susie Layman www.threadsonmysocks.blogspot.com Summer Taffy Bolster Pillows are easy to sew on your machine and one can easily be made in a day. They look great when grouped with pillows of other shapes and sizes and are perfect for a girl’s room or perched on your favorite chairs. Instructions are provided for both ruffled and pleated ends. Finished size - 16” x 4”. Fabrics Needed Fabric A 1 fat quarter Fabric B 1 fat eighth Fabric C* ¼ yard straight cut Fabric D* ¼ yard straight cut *Fabric C can be used for both the inside and outside of the rue or pleat at the end of the pillow. If so, eliminate fabric D and replace with ⁄ yard of fabric C. Materials Needed Pellon® 987F Fusible Fleece ½ yard Pellon® Perfect Loft® Cluster Fiber Fill 1 bag Thread Tools Needed Sewing machine and related supplies Rotary cutter and related supplies www.pellonprojects.com Graphic Artist Alexandra Henry PERMISSION IS GIVEN TO REPRODUCE FOR PERSONAL USE ONLY ©2014 - PCP Group, LLC www.pellonprojects.com Assembly Seam allowance is ½” unless otherwise noted. Step 1. Cutting Instructions. Fabric A Cut one 17” x 16” rectangle for outer pillow body Fabric B Cut two 5” circles using the template found on page 3 Fabric C Cut two 3” x width of fabric strips for outer rue/pleat* Fabric D Cut two 3” x width of fabric strips for inside rue/pleat* Fusible Fleece Cut one 16” x 15” rectangle Cut two 5” circles using the template found on page 3 *If fabric C is used for inside and outer rue, eliminate the cut for fabric D and cut two 5” x width of fabric from fabric C. -

Textile Society of America Newsletter 21:3 — Fall 2009 Textile Society of America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Newsletters Textile Society of America Fall 2009 Textile Society of America Newsletter 21:3 — Fall 2009 Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews Part of the Art and Design Commons Textile Society of America, "Textile Society of America Newsletter 21:3 — Fall 2009" (2009). Textile Society of America Newsletters. 56. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews/56 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Newsletters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. T VOLUME 21 NUMBER 3 FALL, 2009 S A Conservation of Three Hawaiian Feather Cloaks by Elizabeth Nunan and Aimée Ducey CONTENTS ACRED GARMENTS ONCE to fully support the cloaks and and the feathers determined the worn by the male mem- provide a culturally appropriate scope of the treatment. 1 Conservation of Three Hawaiian bers of the Hawaiian ali’i, display. The museum plans to The Chapman cloak is Feather Cloaks S or chiefs, feather cloaks and stabilize the entire collection in thought to be the oldest in the 2 Symposium 2010: Activities and capes serve today as iconic order to alternate the exhibition collection, dating to the mid-18th Exhibitions symbols of Hawaiian culture. of the cloaks, therefore shorten- century, and it is also the most 3 From the President During the summer of 2007 ing the display period of any deteriorated. -

Backyard Homesteading Fair 2019

Backyard Homesteading Fair 2019 May 10-11, 2019 Friday at a Glance Time Raspberry Stage Strawberry Stage Blackberry Stage Exhibitor Area 10 Landscaping with Native Budgeting Goat-Hoof Trimming and Plants Vaccination 11 Raising Chickens/ Using Essential Oils Flower Arranging Making Wheat Bread Producing Eggs 12 Pioneer Quilting, History Solar/Off Grid Plant Walk Goat-Hoof Trimming and of Quilting Vaccination 1 Landscaping with Cold Process Soapmak- Spinning - Wool and Fi- Drought Tolerant Plants ing ber Demonstration 2 Raising Rabbits Butchering Making Rolls 3 Aquaponics Simplify Gardening with Quilting Essential Oils for Inflam- T-Tape Drip Irrigation mation and Pain 4 Mosquito Proofing your How to Eat What’s Eat- Sourdough Starters and Homestead ing Your Garden Bread 5 Caring for Fruit Trees Cultured Foods Essential Oils - Immune Support Saturday at a Glance Time Raspberry Stage Strawberry Stage Blackberry Stage Exhibitor Area 10 Getting started with Processing Rabbit Planting and Pruning Using a 3 point Tiller and Goats Trees Box Blade on a Compact Tractor 11 Learn about Canning by Making Tools out of Making Wheat Bread Making Jam! Trash 12 Converting to Solar Midwife Using a 3 point Tiller and Box Blade on a Compact Tractor 1 Backyard Beekeeping Crocheting Gopher Trapping Herb Walk 2 Cultured Foods Soapmaking Making Rolls 3 Growing Cut Flowers Cooking with Garlic Essential Oils for Inflam- mation and Pain 4 Herbal Medicine in Your Make Simple Farm Style Sourdough Starters and Own Backyard Cheese Bread 5 Footznology Sewing Essential Oils - Immune Support Friday Raspberry Stage 10 am – Using Native Plants in residential landscapes – Steve Paulsen, Native Roots LLC Come and learn about what native plants to use and where to use them. -

Copyright Law and Quilted Art, 9 J. Marshall Rev. Intell. Prop. L

THE JOHN MARSHALL REVIEW OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW PATCHWORK PROTECTION: COPYRIGHT LAW AND QUILTED ART MAUREEN B. COLLINS ABSTRACT Historically, quilts have been denied the same copyright protection available to any other expression in a fixed medium. When quilts have been considered protectable, the protectable elements in a pattern have been limited, or the application of the substantial similarity test has varied widely. One possible explanation for this unequal treatment is that quilting is viewed as 'women's work.' Another is that quilts are primarily functional. However, quilts have evolved over time and may now be expensive collectible pieces of art; art that deserves copyright protection. This article traces the history of quilt making, addresses the varying standards of protection afforded to quilts and concludes that consistent and comprehensive protection is needed for this art form. Copyright © 2010 The John Marshall Law School Cite as Maureen B. Collins, Patchwork Protection: Copyright Law and QuiltedArt, 9 J. MARSHALL REV. INTELL. PROP. L. 855 (2010). PATCHWORK PROTECTION: COPYRIGHT LAW AND QUILTED ART MAUREEN B. COLLINS * INTRODUCTION When is a quilt a blanket and when is it art? This question takes on greater importance as the universe of quilted art expands and changes. Once relegated to attics and church craft bazaars, the quilt has come out of the closet. Today, quilts are found in museums 2 and corporate headquarters. 3 They are considered to be among the most collectible "new" forms of art. 4 Quilting is a multi-million dollar industry. 5 Handmade quilts fetch asking prices in the tens of thousands of dollars. -

Quilts As Visual Texts Marcia Inzer Bost Kennesaw State University

Kennesaw State University DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University Dissertations, Theses and Capstone Projects Fall 12-2010 Quilts as Visual Texts Marcia Inzer Bost Kennesaw State University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/etd Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Bost, Marcia Inzer, "Quilts as Visual Texts" (2010). Dissertations, Theses and Capstone Projects. Paper 418. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses and Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Quilts as Visual Texts By Marcia Inzer Bost A capstone project submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Professional Writing in the Department of English In the College of Humanities and Social Sciences of Kennesaw State University Kennesaw, Georgia 2010 Dedication The capstone project is dedicated to those who gave me the quilts and the knowledge of quilts that I have used for this project: My mother, Julia Layman Inzer, whose quilts I am finishing; Her mother, Alma Lewis Layman, who quilted my early quilts and whose eccentric color choices inspired me to study quilt design; Her mother, Molly Belle Lewis, who left a masterpiece quilt to whose standards I aspire; My father’s sister, Barbara Inzer Smith, who always has the quilting advice I need; Her mother and my grandmother, Grace Carruth Inzer, whose corduroy quilt provides warmth on a cold day; and Her mother, Bertha Carroll Carruth, whose example of a strong, independent woman still inspires me and whose quilts still grace family beds. -

Alef-Bet Patchwork Quilt

Women’s League for Conservative Judaism CH #24 ALEF BET INSTANT PATCHWORK QUILT Patchwork and quilting are two separate arts that were combined by the early settlers of this country to make beautiful quilts. Patchwork is very simple, requiring only accuracy in making the units. The sewing of patchwork consists only of a straight seam. Quilting is the process of sewing the layers of quilt together by hand. Patchwork and quilting, while pleasant to do, take time and patience – but are indeed worth it. Instant patchwork quilting is fun to do, for in no time at all, beautiful and lasting easy care quilts, comforters and throws can be made for loved ones. The quilts can be made quickly because you use material with a patchwork design for the top layer of your quilt (there is no need to sew squares together). This patchwork material may be bought at your yard goods department or you may use a “patchwork design” sheet found in the line department. Bed sheets are excellent to use for both top and lining of your quilt. If you buy the no-iron sheets, they are practically care-free and come in widths to fit all beds. MATERIALS: 1. Patchwork material – fast dye, cotton fabric. 2. Lining – fast dye, cotton fabric of same good quality as top. 3. Scraps of plain colored material for alphabet. 4. Long needle with large eye. 5. Small ball of matching or contrasting yarn. 6. Batting – enough for 1 or 2 layers (I used two for added puffiness) 7. Dining room table or large work table. -

Heart Patchwork Quilt | Pottery Barn Kids 5/15/19, 10�05 AM

Heart Patchwork Quilt | Pottery Barn Kids 5/15/19, 1005 AM Start earning 10% back in Rewards with the Pottery Barn Credit Card. Learn more > POTTERY BARN PB/APT PB MODERN|BABY BABY KIDS TEEN DORM Williams Sonoma WS Home west elm Rejuvenation Mark and Graham | Ship To: SIGN IN REGISTRY KEY REWARDS FAVORITES TRACK YOUR ORDER What are you looking for? New Baby Kids Furniture Bedding Rugs Windows Bath Decor Backpacks & Lunch Baby Gear Beach Gifts Sale PB Modern Baby Up to 50% off Spring Furniture Sale Up to 60% off 25% off 20-40% off Flash Sale: 40% off Backpacks, Lunch & More Beach Towels, Totes & More All Kids' Bedding Ready to Ship Comfort Swivel Rocker Home > Bedding > Quilts & Comforters > Heart Patchwork Quilt Heart Patchwork Quilt Recently $32.50 – $189 Viewed Sale $12.99 – $74.99 CHOOSE ITEMS BELOW Earn $25 in rewards* for every $250 spent with your Pottery Barn Credit Card. Learn More OVERVIEW Spread the love over their sleep space with our Heart Patchwork Quilt. Pieced together with pastel-colored hearts, this quilt provides lasting comfort and charming style to their bed. DETAILS THAT MATTER Made of 100% cotton. Woven cotton gives the fabric a soft finish while providing durability and ultimate breathability. Quilt is expertly stitched by hand. Quilt is filled with 50% cotton and 50% polyester batting. Quilt and shams reverse to solid pink color. VIEW LARGER Roll Over Image to Zoom Shams have center tie closures. KEY PRODUCT POINTS Rigorously tested to meet or exceed all required and voluntary safety standards. Pottery Barn Kids exclusive. -

Quilt Documentation Projects 1980-1989: Exploring the Roots of a National Phenomenon

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Public Access Theses and Dissertations from Education and Human Sciences, College of the College of Education and Human Sciences (CEHS) 7-2010 Quilt Documentation Projects 1980-1989: Exploring the Roots of a National Phenomenon Christine Humphrey University of Nebraska at Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cehsdiss Part of the Education Commons Humphrey, Christine, "Quilt Documentation Projects 1980-1989: Exploring the Roots of a National Phenomenon" (2010). Public Access Theses and Dissertations from the College of Education and Human Sciences. 84. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cehsdiss/84 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Education and Human Sciences, College of (CEHS) at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Public Access Theses and Dissertations from the College of Education and Human Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. QUILT DOCUMENTATION PROJECTS 1980-1989: EXPLORING THE ROOTS OF A NATIONAL PHENOMENON by Christine Humphrey A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: Textiles, Clothing, & Design Under the Supervision of Professor Patricia Crews Lincoln, Nebraska July, 2010 QUILT DOCUMENTATION PROJECTS 1980-1989: EXPLORING THE ROOTS OF A NATIONAL PHENOMENON Christine Elizabeth Humphrey, M.A. University of Nebraska, 2010 Adviser: Patricia Crews The documenting of thousands of quilts by small groups throughout the United States was one of the most notable parts of the 1980s surge of interest in quilt history. -

Free Project Sheet

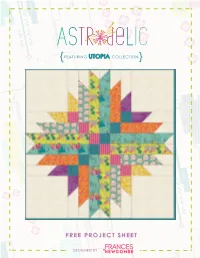

{ FEATURING UTOPIA COLLECTION} FREE PROJECT SHEET DESIGNED BY : QUILT DESIGNED BY FRANCES NEWCOMBE KIT QUANTITY UT-24502 1/8 yd. UT-24509 1/4 yd. UT-24507 1/4 yd. UT-24204 1/8 yd. FINISHED SIZE: 42" X 42" UT-14501 1/8 yd. To download the instructions UT-14505 1/4 yd. UT-14503 1/4 yd. for this pattern visit UT-24506 3/8 yd. NE-104 1 yd. artgalleryfabrics.com Backing 1 1/2 yd. by UT-14500 UT-14501 UT-14502 UT-14503 UT-14504 Dreamlandia Atomic Influx Perse Specks of Rambutan Megalopolitan Dim Orni Bioluminescence Illuminated FANTASY CITY FERVOR UT-14505 UT-14506 UT-14507 UT-14508 UT-14509 Chatter Pods Citrica Lucid Hills Amber Paradise Dwellers Vivid Urban Sprawl Magenta Aglow Sapling Mango UT-24500 UT-24501 UT-24502 UT-24503 UT-24504 Dreamlandia Atomic Influx Alloy Specks of Carambola Megalopolitan Glim Orni Incandescence Irradiated REVERIE CITY WINTER UT-24505 UT-24506 UT-24507 UT-24508 UT-24509 Chatter Pods Menta Lucid Hills Jade Paradise Dwellers Urban Sprawl Grass Aglow Sapling Sloe Neon © 2014 Courtesy of Art Gallery Quilts LLC. All Rights Reserved. 3804 N 29th Ave. Hollywood, FL 33020 PH: 888.420.5399 FX: 425.799.6103 FABRICS DESIGNED BY FRANCES NEWCOMBE FOR ART GALLERY FABRICS QUILT DESIGNED BY Karen Turchan CUTTING DIRECTIONS FINISHED SIZE: 42" X 42" ¼" seam allowances are included. WOF means width To download the instructions of fabric. for this pattern visit One (1) 3 1/2" x WOF strip from fabric A Sub cut strip into four (4) 3 1/2" X 6 1/2" strips artgalleryfabrics.com Two (2) 3 1/2" x WOF strips from fabric B Sub cut strip into four (4) 3 1/2" x 12 1/2" strips Two (2) 3 1/2" x WOF strips from fabric C Sub cut strip into four (4) 3 1/2" x 18 1/2" strips FABRIC REQUIREMENTS One (1) 3 1/2" x WOF strip from fabric D Sub cut strip into six (6) 3 1/2" squares Fabric A UT-24502 1/8 yd. -

The Cutter Quilt Fad, 1980 to Present

The Cutter Quilt Fad, 1980 to Present: A Case Study in Value-Making in American Quilts A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at George Mason University by Rebecca H. McCormick Bachelor of Arts St. Edward’s University, 2010 Director: Jennifer Van Horn, Professor Department of History of Decorative Arts Fall Semester 2013 George Mason University Fairfax, VA This work is licensed under a creative commons attribution-noderivs 3.0 unported license. ii DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this thesis to my parents who made me who I am and to my husband who never asked, “So what are you going to do with that degree?” iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the tireless work and never-ending questions of my advisor, Jennifer Van Horn. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Figures ................................................................................................................... vii Abstract ............................................................................................................................ viii Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One: “Why Not Wear Them?” .............................................................................. 4 Dead Quilts and Cutter Quilts ......................................................................................... 5 The History of Dead Quilts ............................................................................................ -

The Beginnings of Quilting and Patchwork in Antiquity - Two Articles on the History of the Craft Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE BEGINNINGS OF QUILTING AND PATCHWORK IN ANTIQUITY - TWO ARTICLES ON THE HISTORY OF THE CRAFT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Various | 34 pages | 15 Mar 2011 | Read Books | 9781446542347 | English | Alcester, United Kingdom The Beginnings of Quilting and Patchwork in Antiquity - Two Articles on the History of the Craft PDF Book Quilt making was taught to the young daughters in early days. Getting Started. Padded wear could be put on under armour to make it more comfortable, or even as a top layer for those who couldn't afford metal armour. For a time, the trend in wholecloth quilting was a preference for all-cotton white quilts. Obviously, quilting as a craft came to America with the early Puritans. Can I get hurt using a quilting machine? Playing on the word crazy they gave plans for "crazy" tea parties using mismatched invitations and other "crazy" themes. Wrap Up. This meant women no longer had to spend time spinning and weaving to provide fabric for their family's needs. In the lateth-century quilt revival, teachers like Elly Sienkiewicz repopularized the Baltimore Album style. Quilting in Modern Times Quilting has experienced a revival over the last 60 years. The wool wholecloth quilt was made in by Martha Crafts Howard. One of the most popular exhibits was the Japanese pavilion with its fascinating crazed ceramics and asymmetrical art. The story of a family was also commemorated in hand-pieced fabric. Essentially, a knee lifter is an attachable part that lets you control the position of a presser foot with your knee. Often these quilts provide the only decoration in a simply furnished home and they also were commonly used for company or to show wealth.