The Cutter Quilt Fad, 1980 to Present

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright Law and Quilted Art, 9 J. Marshall Rev. Intell. Prop. L

THE JOHN MARSHALL REVIEW OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW PATCHWORK PROTECTION: COPYRIGHT LAW AND QUILTED ART MAUREEN B. COLLINS ABSTRACT Historically, quilts have been denied the same copyright protection available to any other expression in a fixed medium. When quilts have been considered protectable, the protectable elements in a pattern have been limited, or the application of the substantial similarity test has varied widely. One possible explanation for this unequal treatment is that quilting is viewed as 'women's work.' Another is that quilts are primarily functional. However, quilts have evolved over time and may now be expensive collectible pieces of art; art that deserves copyright protection. This article traces the history of quilt making, addresses the varying standards of protection afforded to quilts and concludes that consistent and comprehensive protection is needed for this art form. Copyright © 2010 The John Marshall Law School Cite as Maureen B. Collins, Patchwork Protection: Copyright Law and QuiltedArt, 9 J. MARSHALL REV. INTELL. PROP. L. 855 (2010). PATCHWORK PROTECTION: COPYRIGHT LAW AND QUILTED ART MAUREEN B. COLLINS * INTRODUCTION When is a quilt a blanket and when is it art? This question takes on greater importance as the universe of quilted art expands and changes. Once relegated to attics and church craft bazaars, the quilt has come out of the closet. Today, quilts are found in museums 2 and corporate headquarters. 3 They are considered to be among the most collectible "new" forms of art. 4 Quilting is a multi-million dollar industry. 5 Handmade quilts fetch asking prices in the tens of thousands of dollars. -

Alef-Bet Patchwork Quilt

Women’s League for Conservative Judaism CH #24 ALEF BET INSTANT PATCHWORK QUILT Patchwork and quilting are two separate arts that were combined by the early settlers of this country to make beautiful quilts. Patchwork is very simple, requiring only accuracy in making the units. The sewing of patchwork consists only of a straight seam. Quilting is the process of sewing the layers of quilt together by hand. Patchwork and quilting, while pleasant to do, take time and patience – but are indeed worth it. Instant patchwork quilting is fun to do, for in no time at all, beautiful and lasting easy care quilts, comforters and throws can be made for loved ones. The quilts can be made quickly because you use material with a patchwork design for the top layer of your quilt (there is no need to sew squares together). This patchwork material may be bought at your yard goods department or you may use a “patchwork design” sheet found in the line department. Bed sheets are excellent to use for both top and lining of your quilt. If you buy the no-iron sheets, they are practically care-free and come in widths to fit all beds. MATERIALS: 1. Patchwork material – fast dye, cotton fabric. 2. Lining – fast dye, cotton fabric of same good quality as top. 3. Scraps of plain colored material for alphabet. 4. Long needle with large eye. 5. Small ball of matching or contrasting yarn. 6. Batting – enough for 1 or 2 layers (I used two for added puffiness) 7. Dining room table or large work table. -

Heart Patchwork Quilt | Pottery Barn Kids 5/15/19, 10�05 AM

Heart Patchwork Quilt | Pottery Barn Kids 5/15/19, 1005 AM Start earning 10% back in Rewards with the Pottery Barn Credit Card. Learn more > POTTERY BARN PB/APT PB MODERN|BABY BABY KIDS TEEN DORM Williams Sonoma WS Home west elm Rejuvenation Mark and Graham | Ship To: SIGN IN REGISTRY KEY REWARDS FAVORITES TRACK YOUR ORDER What are you looking for? New Baby Kids Furniture Bedding Rugs Windows Bath Decor Backpacks & Lunch Baby Gear Beach Gifts Sale PB Modern Baby Up to 50% off Spring Furniture Sale Up to 60% off 25% off 20-40% off Flash Sale: 40% off Backpacks, Lunch & More Beach Towels, Totes & More All Kids' Bedding Ready to Ship Comfort Swivel Rocker Home > Bedding > Quilts & Comforters > Heart Patchwork Quilt Heart Patchwork Quilt Recently $32.50 – $189 Viewed Sale $12.99 – $74.99 CHOOSE ITEMS BELOW Earn $25 in rewards* for every $250 spent with your Pottery Barn Credit Card. Learn More OVERVIEW Spread the love over their sleep space with our Heart Patchwork Quilt. Pieced together with pastel-colored hearts, this quilt provides lasting comfort and charming style to their bed. DETAILS THAT MATTER Made of 100% cotton. Woven cotton gives the fabric a soft finish while providing durability and ultimate breathability. Quilt is expertly stitched by hand. Quilt is filled with 50% cotton and 50% polyester batting. Quilt and shams reverse to solid pink color. VIEW LARGER Roll Over Image to Zoom Shams have center tie closures. KEY PRODUCT POINTS Rigorously tested to meet or exceed all required and voluntary safety standards. Pottery Barn Kids exclusive. -

History of Quilting

History of Quilting When the first settlers came to this country they brought with them their quilting skills. New fabric was hard to come by, so fabric for clothing and for quilts had to be used and reused saving as much as possible from worn clothing. Thus the patchwork quilt was born. Scraps of fabric were cut into geometric patterns that fit together into larger blocks of design. Many of these patterns have been passed through generations, created by the ingenuity of our ancestors and traded within communities. Names for particular patterns sometimes changed as they moved from one part of the country to another, reflecting the environment within which it was named. (i.e. a pattern called the pine tree pattern in Connecticut might be named bear’s path in Ohio). Quilt making is an art form that both individuals, as well as groups of people participated in. From the lore surrounding quilt making we learn that parents passed the skills for quilt making on to their children at a very young age. The children would start with small patches of fabric, and learn to sew the very fine stitches needed for beautiful and elaborate quilts. Historically, quilting has generally been practiced by, and associated with women. This could be because the sewing skills needed to make a quilt have always been an integral part of women’s lives. Learning how to sew was such an important skill for girls to have that it was taught and practiced in the home and at school. Women of all classes participated in this form of expression. -

Add a Bit of British Chic to Your Bedroom with Some Quilted Union Jack Pillows

Add a bit of British chic to your bedroom with some quilted Union Jack pillows Union Jack Pillows (makes two day-sized pillows) You will need: 2 x day pillows lots of silk ribbon, in white Sewing Machine 1 metre of dark blue and black Scissors quilted fabric dark blue, white and black Pins thread 1 metre of pink silky fabric Tailor’s chalk 1 metre of dark blue interfacing (optional) silky fabric Paper (for your templates) inSTruCTionS 1 Start by measuring the pillows. The ones i used measured 60cm x 38cm. Create a rectangle template on the paper pattern using these measurements. 2 draw around the template on to your fabric and cut out two rectangles of your covering fabric (the dark blue quilted) and two rectangles of the backing fabric (the silky dark blue). Then fold your template in half and cut two more half rectangles (measuring 30cm x 38cm) of the backing fabric. 3 now it’s time to make a paper template for the cross, measuring 60cm wide x 38cm tall to match your pillows and 7cm thick. inSTruCTionS 4 Trace around the cross on to the silky pink fabric and cut out two silk crosses. Put these to the side for the moment. if you’re using quite a thin silky fabric, you can iron some interfacing on to the back of your crosses to strengthen the colour. 5 lay the cover fabric down on a flat surface and place the paper cross template on top. now, lay down two strips of white ribbon from the corner in to the centre of the cross and cut to size. -

Land of Nod Patchwork Quilt

Land of nod patchwork quilt Finding the perfect kids quilt or comforter is easy when you browse our wide selection. Shop for bedding themes like sports, floral, space, safari & more.Baby Quilts · Builder's Quilt · Black & White Geometric Quilt · Solar Systems Go Quilt. Our baby quilts are crafted with quality and care, so they'll still be around when your little one has outgrown their crib. A very charming % cotton quilt and pillowcases from Land of Nod. Features grey The Land Of Nod PATCHWORK Pink Green Duvet Cover Twin. $ Land of Nod "Patchwork Quilt" Twin Duvet in Home & Garden, Kids & Teens at Home, Bedding, Duvet Covers | eBay. @Overstock - Your daughters room will look great with one of these stylish bedding quilt sets. Each quilt features a unique soft green, light blue, and pink. Kids' Bedding: Girls' Doll Dress Theme Patchwork Quilt - Twin Quilt by The Land of Nod Just got for lyla love it girly but not over the top. Queen Comforter Land of Nod Equestrian Patchwork Quilt Horse & Rider Boots 88 x 90 A Magnificent % cotton Equestrian Comforter In the Center is an. 24". 4 Pegs. M2M Land of Nod Handpicked Patchwork. Personalized Coat Rack. Hand Sewn Baby Quilt, Land of Nod Nursery Rhyme Crib Quilt, Wynken. Kids' Bedding: Girls' Indian Print Themed Patchwork Quilt - Twin Indian Patchwork Quilt from The Land of Nod. Kids' Bedding: Girls' Indian Print Themed. This Spring's deal is going fast! 30% Off land of nod - peacock baby quilt, baby quilts. Now $ Was $ Suzy Quilts is rooted in a deep love for the heritage and tradition of quilting and a Patchwork, QuiltCon Magazine and Modern Quilts Unlimited and has worked in large corporations such as Toyota and Land of Nod as well as Birch Fabrics. -

NEW for Spring!

QUILTING | SEWING | FABRIC | NOTIONS All NEW ExclusivesExclusives forfor Spring!Spring! Bow Ties In Motion Kit, page 8 MARCH 2021 AnniesCraftStore.com QSA1 CrochetCraft & Craft Store Catalog inside 2–47, 84 Quilt Patterns & Fabric 48–58 Sewing Patterns 59–74 Quilt & Sew Supplies 75–82 Crochet Exclusively Annie’s NEW! Vintage Garden Quilt Pattern skill level key This is perfect for springtime! Use 1930s reproduction prints to create this vintage-looking quilt! Finished size: 54" x 67". Beginner: For first-time Skill Level: Intermediate stitchers. Y886586 Print $8.99 Easy: Projects using basic A886586 Download $7.99 stitches. Intermediate: Projects with a NEW! variety of stitches and mid-level Quilting Fast & Fun QUILTING Fast & Fun shaping. Quilts for Kids Experienced: Projects using ™ Quilts for Kids Every child loves advanced techniques and a quilt of their stitches. 10Creative own—it’s like Designs For Kids getting wrapped Of All in a big hug. Fast FAST & FUN QUILTS FOR KIDS Ages & Fun Quilts for Kids has quilts our guarantee designed for kids of all ages from If you are not completely satisfied baby to teen. with your purchase, you may Skill Level: return it, no questions asked, for Confident a full and prompt refund. Beginner Annie’s 141479 141479 $9.99 Connect with us on 2 quilt patterns & fabric Facebook.com NEW! Magnolia Quilt Pattern The magnolia flower represents endurance, eternity and long life. Such a sweet reminder is the KIT inspiration for this quilt design, from the appliqué wreath to the “petal” blocks. Skill Level: Intermediate 422689 $10.99 NEW! Jardin Bleu Quilt Kit Stitch up this quilt that uses a sashing made of 21/2" squares! This kit comes with all of the fabrics (from Nancy Mink’s Collection Violette) to make the quilt top and binding. -

06-0003 ETF TOC J.Indd

06-0003 ETF_39_45_j 6/16/06 12:50 PM Page 39 ONGRESS C IBRARY OF © L Two women put the final touches on a quilt featuring a fan design that was popular in the 1930s. The quilt is stretched on a frame to make it easier for the women to work on it. Quilting An American Craft BY P HYLLIS M C I NTOSH quilt can warm a bed, decorate a wall, comfort a child in her crib or a AA soldier at war. A quilt also can tell a story, commemorate an event, honor the dead, unite a community, and reflect a culture. Quite a resume for a piece of needlework! And evidence, too, that quilts have captured the hearts and imaginations of Americans unlike any other form of folk art. Quilting has enjoyed a long tradition in the United States and today is more popular than ever. According to a 2003 survey by Quilters Newsletter Magazine, there are more than 21 million American quilters (representing 15 percent of U.S. households), and they spend $2.27 billion a year on their craft. The most dedicated among them are like- ly to have an entire room in their house devoted to quilting and to own more than $8,000 worth of quilting supplies. Their creations range from everyday items such as bed coverings, clothing, and table mats to treasured heirlooms and museum quality works of art. The word quilt itself has come to describe far more than stitched pieces of fabric. Civil rights activist Jesse Jackson used the word to describe American society when he said: “America is not like a blanket––one piece of unbroken cloth, the same color, the same texture, the same size. -

"The Patchwork Quilt"

Planning and Building Livable, Safe & Sustainable Communities The Patchwork Quilt Approach Edward A. Thomas, Esq. Alessandra Jerolleman, PhD, MPA, CFM Terri L. Turner, AICP, CFM Darrin Punchard, AICP, CFM Sarah K. Bowen, CFM Special Edition for the Natural Hazard Mitigation Association International Mitigation Practitioners Symposium, 2013 2 _________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents I. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 5 II. The Process ..................................................................................................................................... 8 III. Creating the Patchwork Quilt ......................................................................................................... 9 A) The Quilter: Community Leadership with Vision .................................................................... 9 B) The Pattern: Getting Technical Assistance ................................................................................ 9 C) A Necessary Step to Developing the Pattern: Writing the Hazard Mitigation Plan ................ 10 D) National Disaster Recovery Framework…….……………………………………….… ........... …………12 E) National Mitigation Framework......................................................................................................................12 IV. Finding Technical Assistance ........................................................................................................ -

THE PATCHWORK QUILT in Quilt Books, So That Students May See the Enormous Variety of Patterns Author: Valerie Flournoy and Colors Used in Making Quilts

Obtain some photographs of quilts, such as those found on calendars and THE PATCHWORK QUILT in quilt books, so that students may see the enormous variety of patterns Author: Valerie Flournoy and colors used in making quilts. Invite families to bring a quilt to school. Ask Illustrator: Jerry Pinkney students to notice the differences among applique, embroidered, and patch- Publisher: Dial Books for Young Readers work quilts. Discuss the patterns, shapes, and evidence of symmetry they see in both patches and stitching. Have them look for quilt blocks, or squares, THEME: and notice how they are formed and how they fit together. Some of the family Coming in all sizes, shapes and colors, families are as varied as patchwork quilts may have stories to go with them—allow time for sharing these stories. quilts with their own special brand of love. Invite a quilter into the classroom to do a demonstration. Have this person PROGRAM SUMMARY: show the stages in the process, e.g., deciding on a pattern, selecting colors Using scraps cut from the family’s old clothing, a young girl learns the secret and fabric, cutting pieces, fitting them together and stitching, assembling quilt ingredient in her Grandma’s special quilt of memories. This episode leads blocks into a larger piece, the use of the cotton batting, and the actual quilting. LeVar to the Boston Children’s Museum, where he discovers kids learning to Make a paper quilt featuring students and their grandparents. Cut construc- make their own brightly colored patchwork quilts. Then he explores how three tion paper squares (5 x 5 inches). -

Please Click Here for PDF Version of the Catalogue

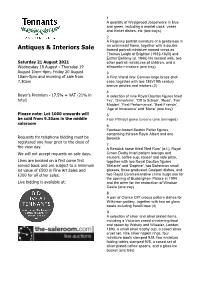

1 A quantity of Wedgwood Jasperware in blue and green, including a mantel clock, vases and trinket dishes, etc (two trays) 2 A Regency portrait miniature of a gentleman in an oval metal frame, together with a double Antiques & Interiors Sale framed portrait miniature named verso as Thomas Leight of Brighton (1932-1820) and Esther Bellamy (d. 1846) his second wife, two Saturday 21 August 2021 other portrait miniatures of children, and a Wednesday 18 August - Thursday 19 silhouette miniature (one tray) August 10am-4pm, Friday 20 August 3 10am-5pm and morning of sale from A First World War German large brass shell 7.30am case, together with two 18th/19th century bronze pestles and mortars (3) 4 Buyer’s Premium - 17.5% + VAT (21% in A selection of nine Royal Doulton figures titled total) 'Ivy', 'Dinnertime', 'Off to School', 'Rose', 'Fair Maiden', 'First Performance', 'Best Friends', 'Age of Innocence' and 'Marie' (one tray) Please note: Lot 1000 onwards will 5 be sold from 9.30am in the middle Four Pillivuyt game tureens (one damaged) saleroom 6 Fourteen boxed Beatrix Potter figures, comprising thirteen Royal Albert and one Requests for telephone bidding must be Beswick registered one hour prior to the close of 7 the view day. A Beswick horse titled 'Red Rum' (a.f.), Royal We will not accept requests on sale days. Crown Derby Imari pattern teacups and saucers, coffee cup, saucer and side plate, Lines are booked on a first come first together with two Royal Doulton figures served basis and are subject to a minimum 'Melanie' and 'Daphne', two Bohemian small lot value of £500 in Fine Art Sales and glasses, three graduated Coalport dishes, and £200 for all other sales. -

Member's Guide

Our Quilt Heritage Compiled By: Tracy M. Cowles, Family and Consumer Sciences Agent, Butler County Member’s Guide MOTHER’S PATCHWORK QUILT History of Quilting Quilting did not originate in America, I see my mother’s patchwork quilt although it certainly took on a new form Upon my bed upstairs in this country. The earliest known And stitched into each tiny piece quilted item is a garment found on the statue of an Are all her love and care Egyptian pharaoh who lived about 3400 BC. I see my sister’s dresses, Quilted garments were worn for protection under A piece of mother’s skirt, the armor of the crusading knights in the Middle A bit of brother’s rompers, Ages. They were all made of whole pieces of cloth, A square of daddy’s shirt as were the “bed rugs” made in Europe by men in tailor guilds. Although patchwork was developed I see her work worn hands much later, the appliqué technique was widely used By fading evening light, to make the ornamental unquilted hangings for the Piecing tiny diamonds churches of the Middle Ages. Appliqué also Far into the night decorated the robes of the royal elite. A square of yellow, Quilting in America Bits of blue and red, Oh! I am so proud Quilted garments and bedcovers were To spread it on my bed very important to America’s early settlers, although it is not known exactly How I cherish that old quilt when they were introduced. Most quilt scholars A thing of beauty rare, agree, however, that the use and development of For I saw my mother stitching quilting came from English and Dutch immigrants.