EC 072 851 Bureau of Education for the Handicapped

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Social History of Quilt Making in America

The Social History of Quilt Making in america In his seminal book, The Shape of Time: “Artistic production, whilst distinct, belongs to the ‘whole range of Remarks on the History of Things (1962), man-made things, including all tools and written’ and ’such things George Kubler expressed the view that the mark the passage of time with greater accuracy than we know, and concept of art should be expanded to include they fill with shapes of a limited variety’… ‘Everything made now is all man-made objects. His approach either a replica or a variant of some thing made a little time ago and eliminates the distinction between artifacts so on back without break to the first morning of human time’. and “major” art – architecture, painting, (.Kubler, 2007: 1) The demarcation between art and craft, an invention sculpture. Drawing on the fields of of the Renaissance mind, therefore, becomes unimportant when anthropology and linguistics, Kubler replaced considering objects of utilitarian nature. This suggests that quilts, and the notion of style as the basis for histories specifically American quilts, rightfully deserve the distinction of art, of art with the concept of historical sequence without qualification. and continuous change across time. Quilts of Gee’s Bend When the exhibition of the quilts of Gee’s Bend * first opened at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 2003, an article in the Wall Street Journal began, in part: “Museum curators have a lot to worry about in these tough times: attendance, security, damaged art. And now…bedbugs. Created by four generations of African-American Some of the biggest blockbuster exhibits of recent years have nothing to quilters from the isolated hamlet of Gee’s Bend, do with Van Gogh and Vermeer – they are all about quilts. -

Fear 18 Killed in Crash of Blimp

Party fjoife (odsy. High to Distrib'utfon fbe 7tf, Mofdy fair tonight and tomorrow. Low tonight in W*. Today High tomorrow, 88, Variable winds today and tomorrow. See 14,050 page 2. 'stet An Independent Newspaper Under Same Ownership Since 1878 BY CARRIER Iisued Dally, Monday through Friday, entered u Second CU» Matter 7c PER COPY PAGE ONE /OLUME 82, NO. 233 at th» Post OUIca at Red Bank. N. J.. under the Act of Marcn 3. IS78. RED BANK, N. J., THURSDAY, JULY 7, 1960 fAUE. Wt 3Jc pER WEEK Fear 18 Killed in Crash of Blimp Paper Firm Three Survive Plunge Into Sea May Locate Off Barnegat At Holmdel Atlantic Highlands Officer HOLMDEL - Township offici- als confirmed last night that Concert Standees Missing; Area Man Saved plans are in the offing for a To Be Cared For multi-million-dollar paper pro- LAKEHURST (AP)—A huge Navy blimp crumpled ducts plant to be constructed off RED BANK — Music lovers Rt. 35 near Laurel Ave. were out in force for this bor- in air on a search mission yesterday and crashed "like Valuation of the plant, includ- ough's first free concert of the a sagging banana" into the ocean off the New Jersey ing construction, machinery and summer last night in Marine coast. equipment, has been estimated Park. One airman was killed and 17 feared lost in the at 10 to 15 million dollars. As a result, seating accomo- Mayor James H. Ackerson told datlons for next Wednesday's sunken wreckage. The Register that the plant would concert will be tripled, ac- Three crewmen survived. -

Absent Presence: Women in American Gangster Narrative

Absent Presence: Women in American Gangster Narrative Carmela Coccimiglio Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a doctoral degree in English Literature Department of English Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Carmela Coccimiglio, Ottawa, Canada, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract iii Acknowledgements v Introduction 1 Chapter One 27 “Senza Mamma”: Mothers, Stereotypes, and Self-Empowerment Chapter Two 57 “Three Corners Road”: Molls and Triangular Relationship Structures Chapter Three 90 “[M]arriage and our thing don’t jive”: Wives and the Precarious Balance of the Marital Union Chapter Four 126 “[Y]ou have to fucking deal with me”: Female Gangsters and Textual Outcomes Chapter Five 159 “I’m a bitch with a gun”: African-American Female Gangsters and the Intersection of Race, Sexual Orientation, and Gender Conclusion 186 Works Cited 193 iii ABSTRACT Absent Presence: Women in American Gangster Narrative investigates women characters in American gangster narratives through the principal roles accorded to them. It argues that women in these texts function as an “absent presence,” by which I mean that they are a convention of the patriarchal gangster landscape and often with little import while at the same time they cultivate resistant strategies from within this backgrounded positioning. Whereas previous scholarly work on gangster texts has identified how women are characterized as stereotypes, this dissertation argues that women characters frequently employ the marginal positions to which they are relegated for empowering effect. This dissertation begins by surveying existing gangster scholarship. There is a preoccupation with male characters in this work, as is the case in most gangster texts themselves. -

Mushrooms, Russia, and History: Volume II

MUSHROOMS RUSSIA AND HISTORY BY VALENTINA PAVLOVNA WASSON AND R.GORDON WASSON % VOLUME II PANTHEON BOOKS • NEW YORK COPYRIGHT © 1957 BY R. GORDON WASSON MANUFACTURED IN ITALY FOR THE AUTHORS AND PANTHEON BOOKS INC. 333, SIXTH AVENUE, NEW YORK 14, N. Y. www.NewAlexandria.org/ archive CONTENTS VOLUME II V. THE RIDDLE OF THE TOAD AND OTHER SECRETS MUSHROOMIC (CONTINUED) 14. Teo-Nandcatl: the Sacred Mushrooms of the Nahua 215 15. Teo-Nandcatl: the Mushroom Agape 287 16. The Divine Mushroom: Archeological Clues in the Valley of Mexico 322 17. 'Gama no Koshikake' and 'Hegba Mboddo' 330 18. The Anatomy of Mycophobia 335 19. Mushrooms in Art 351 20. Unscientific Nomenclature 364 Vale 374 BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTES AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 381 APPENDIX I: Mushrooms in Tolstoy's 'Anna Karenina' 391 APPENDIX II: Aksakov's 'Remarks and Observations of a Mushroom Hunter' 394 APPENDIX III: Leuba's 'Hymn to the Morel' 400 APPENDIX IV: Hallucinogenic Mushrooms: Early Mexican Sources 404 INDEX OF FUNGAL METAPHORS AND SEMANTIC ASSOCIATIONS 411 INDEX OF MUSHROOM NAMES 414 INDEX OF PERSONS AND PLACES 421 LIST OF PLATES VOLUME II JEAN-HENRI FABRE. Coprinus tardus Karst. Title-page xxxvra.JEAN-HENRI FABRE. Boletus duriusculus Kalchbr. 218 xxxix. JEAN-HENRI FABRE. Panseolus campanulatus Fr. ex L. 242 XL. Ceremonial mushrooms. Water-color by Michelle Bory. 254 XLI. Accessories to the mushroom rite. Water-color by VPW. 254 xiii. Aurelio Carreras, curandero, and his son Mauro. Huautla de Jimenez, July 5, 1955. Photo by Allan Richardson. 262 xnn. Mushroom stone. Attributed to early classic period, Highland Maya, c. 300 A.D. -

Kirby Interview Steve Rude & Mike Mignola Stan Lee's Words Fantastic Four #49 Pencils Darkseid, Red Skull, Doctor Doom, At

THE $5.95 In The US ISSUE #22, DEC. 1998 A 68- PAGE COLLECTOR ISSUE ON KIRBY’S VILLAINS! AN UNPUBLISHED Kirby Interview INTERVIEWS WITH Steve Rude & Mike Mignola COMPARING KIRBY’S MARGIN NOTES TO Stan Lee’s Words STUNNING UNINKED Fantastic Four #49 Pencils SPECIAL FEATURES: Darkseid, Red Skull, Doctor Doom, Atlas Monsters, . s Yellow Claw, n e v e t S e & Others v a D & y b r THE GENESIS OF i K k c a J King Kobra © k r o w t r A . c Unpublished Art n I , t INCLUDING PENCIL n e PAGES BEFORE m n i a THEY WERE INKED, t r e t AND MUCH MORE!! n E l e v r a M NOMINATED FOR TWO 1998 M T EISNER r e AWARDS f r INCLUDING “BEST u S COMICS-RELATED r PUBLICATION” e v l i S 1998 HARVEY AWARDS NOMINEE , m “BEST BIOGRAPHICAL, HISTORICAL o OR JOURNALISTIC PRESENTATION” o D . r D THE ONLY ’ZINE AUTHORIZED BY THE Issue #22 Contents: THE KIRBY ESTATE Morals and Means ..............................4 (the hows and whys of Jack’s villains) Fascism In The Fourth World .............5 (Hitler meets Darkseid) So Glad To Be Sooo Baaadd! ..............9 (the top ten S&K Golden Age villains) ISSUE #22, DEC. 1998 COLLECTOR At The Mercy Of The Yellow Claw! ....14 (the brief but brilliant 1950s series) Jack Kirby Interview .........................17 (a previously unpublished chat) What Truth Lay Beneath The Mask? ..22 (an analysis of Victor Von Doom) Madame Medusa ..............................24 (the larcenous lady of the living locks!) Mike Mignola Interview ...................25 (Hellboy’s father speaks) Saguur ..............................................30 (the -

Re-Envisioning History: Memory, Myth and Fiction in Literary Representations of the Trujillato

RE-ENVISIONING HISTORY: MEMORY, MYTH AND FICTION IN LITERARY REPRESENTATIONS OF THE TRUJILLATO By CHRISTINA E. STOKES A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2009 1 © 2009 Christina E. Stokes 2 In Memoriam Alvaro Félix Bolaños Luis Cosby 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deepest thanks to all the people who have made this study possible. I deeply thank Dr. Efraín Barradas who has been my mentor and advisor during my years as a doctoral student. His guidance and insight have been invaluable. I also want to the thank the rest of my committee, Dr. Félix Bolaños, Dr. Tace Hedrick, Dr. Reynaldo Jiménez, and Dr. Martín Sorbille, for their help in contextualizing my work and careful reading of this study. I thank Dr. Andréa Avellaneda, Dr. Geraldine Cleary Nichols and Dr. David Pharies for being wonderful teachers and mentors. Many thanks go to the staff of the Department of Spanish and Portuguese, especially Ann Elton, Terry Lopez, and Sue Ollman. I also thank the staff of the Latin American Collection of Smathers Library, Paul Losch and Richard Phillips for their invaluable help in obtaining texts. I would also like to express my gratitude to my mother, Consuelo Cosby and my sister, Angela O’Connell for their encouragement and enthusiasm. Finally, I thank my husband, John and stepdaughter, Shelby for their love and support. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...............................................................................................................4 -

"In and Out" : Segmentary Gang Politics in Los Angeles

”In and out” Segmentary gang politics in Los Angeles Tero Tapani Frestadius University of Helsinki Faculty of Social Sciences Social and Cultural Anthropology Master's thesis November 2009 Page | 1 Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................3 1.1 Research questions and theoretical framework ............................................................................................5 1.2 “No more problems”- note on fieldwork .................................................................................................. 11 1.3 The backdrop ............................................................................................................................................... 14 1.4 L.A. gang basics .......................................................................................................................................... 22 2. The neighborhood ................................................................................................................................26 2.1 “Amputations from the trunk”.................................................................................................................... 26 2.2 A walk in the Hazard Projects .................................................................................................................... 27 2.3 The pathologized neighborhoods of social sciences ................................................................................ -

Was Casimir Pulaski Intersex? and the Back Seem Like Separate Ecosystems

CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE | APRIL CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE Translating Rahm Ben Joravsky 6 Masa Madre takes on Passover Aimee Levitt 9 Black veterans’ new battleground Mariah Karson 11 A new rein Chicago goes all in on Lightfoot THIS WEEK CHICAGOREADER | APRIL | VOLUME NUMBER IN THIS ISSUE TR - TheWorstMotherintheWorldis @ aboutinclusionandmommyissues andYenshowstwoneglectedteens strugglingtogrowup P TB IEC FILM SKKH FOOD&DRINK 19 FestivalPreviewWhatdoesit D EKS 09 FoodFeatureArmedwith meantobeAsianAmerican? C L SK D P JR familyrecipesMasaMadretakes 20 ReviewWithAshIsPurest 30 ShowsofnoteExHexMdou CEAL onPassover WhiteJiaZhangkeremainsthe MoctarPerfumeandmoreshows M EP M masterofdisplacement thisweek A EJL CITYLIFE SWDI 03 StreetViewArapper’sstyle 21 MoviesofnoteGospelof 36 EarlyWarningsJoanna BJ MS startswithhisshoes EurekashowsaBibleBelttownon NewsomIndianGladysKnight S WMD LG 04 TransportationWhatshould thebrinkofchangeShazam!has andmorejustannouncedconcerts G D D C S M EBW Chicagodoaboutcyclistswho retroappealforcomicbookbuff s 36 GossipWolfJohnCorbett M L C don’tplaybytherules? andStyxisathoughtprovoking celebrateshisbookwithfree S C -J moraldramaaboutlifeanddeath barbecuedrummerSpencer FL C PF T A ECS TweedydropsanEPasafrontman CNB D C andmore D C LC NLC CC MDLC S F IG AG OPINION KTH JH JH ARTS&CULTURE 36 SavageLoveDanSavageoff ers IH DJ MK S 14 LitGneshnabemne?Citizen adviceondatingandrespecting K MM B M JRN MO L O Y PotawatomiNationproducesits transwomen P LP KS KR fi rstdictionary -

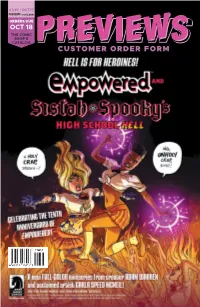

Customer Order Form

#349 | OCT17 PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE OCT 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Oct17 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 9/7/2017 9:56:45 AM Oct17 C2 Abstract.indd 1 9/7/2017 9:13:07 AM INCOGNEGRO: A GRAPHIC RUMBLE VOL. 2 #1 MYSTERY HC IMAGE COMICS DARK HORSE COMICS DAMAGE #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT EMPOWERED & SISTAH SPOOKY’S WITCHBLADE #1 HIGH SCHOOL IMAGE COMICS HELL #1 DARK HORSE COMICS ASSASSINISTAS #1 IDW ENTERTAINMENT THE IMMORTAL MARVEL MEN #1 2-IN-ONE #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT MARVEL COMICS Oct17 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 9/7/2017 4:05:08 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Terry Moore 25th-Anniversary Sketchbook: 8,800 Days of Blondes & Brunette l ABSTRACT STUDIOS Hero Cats Volume 1 HC l ACTION LAB ENTERTAINMENT Babyteeth Volume 1 TP l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Casper and Wendy #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Klaus and the Crisis in Xmasville #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Rocko’s Modern Life #1 Main l BOOM! STUDIOS Belladonna: Fire and Fury #1 l BOUNDLESS COMICS Barbarella #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Grumpy Cat/Garfield HC l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Superb Volume 1: Life after the Fallout TP l LION FORGE 1 Kim Reaper Volume 1: Grim Beginnings TP l ONI PRESS INC. Under #1 l TITAN COMICS Robotech #5 l TITAN COMICS Justice League: The Art of the Film HC l TITAN COMICS Quantum & Woody #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC Shiver: Junji Ito HC l VIZ MEDIA LLC Splatoon Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA LLC So I’m A Spider… So What? Volume 1 GN l YEN PRESS BOOKS 2 In The Night Studio: Illustration After Dark by Dan Brereton -

Open Thesis-Deposit Draft.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Communications THE BRAND AND THE BOLD: CARTOON NETWORK’S BATMAN: THE BRAVE AND THE BOLD AS COMICS-LICENSED CHILDREN’S TELEVISION A Thesis in Media Studies by Zachary Roman © 2011 Zachary Roman Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts May 2011 The thesis of Zachary Roman was reviewed and approved* by the following: Matthew P. McAllister Professor of Communications Thesis Advisor Barbara Bird Associate Professor of Communications Jeanne Lynn Hall Associate Professor of Communications Marie Hardin Associate Dean for Graduate Studies and Research *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT This thesis critiques the animated children's television program, Batman: The Brave and the Bold, debuting in 2008 on Cartoon Network, as a synergistic corporate commodity. In the program, Batman teams up with a guest hero who helps him vanquish the villain. The commodity and commercial functions of this premise is to introduce and promote secondary licensed brands -- the “guest heroes” and “guest villains” -- for synergistic profit based on the current popularity with the program’s anchor brand, Batman. Given Time Warner's ownership of multiple media outlets including Warner Bros. Animation, DC Comics and Cartoon Network, the program serves as a bridge text to usher young consumers of Time Warner content into becoming long-term consumers of more adult iterations of many of these same characters and licenses. The thesis contextualizes the program in the larger scholarly literature of the nature of media licensing, the history of commercialism on children's television, comic books and children's media licensing. -

The Brand and the Bold: Synergy and Sidekicks in Licensed-Based Children’S Television

Spring 2012 Global Media Journal Volume 12, Issue 20 Article 2 The Brand and the Bold: Synergy and Sidekicks in Licensed-based Children’s Television Zachary Roman College of Communications The Pennsylvania State University Matthew P. McAllister, Ph.D. Department of Film-Video & Media Studies College of Communications The Pennsylvania State University Keywords Children’s Television, Synergy, Licensing, Media Brands, Media Promotion, Superheroes, Batman. Abstract This paper examines the animated program Batman: The Brave and the Bold (BB&B), debuting in 2008 on the US cable television Cartoon Network, and related licensing as products of mediated corporate synergy. The program integrates various Time Warner subsidiaries and licensing partners to create a coordinated universe of characters with particular ideological implications for branded character relationships, commodity play, and gender norms. Explored are two elements of BB&B: the number and type of guest heroes and villains on the program and in subsidiary licenses, and the role of Batman in the narrative world of BB&B. By emphasizing the necessary pairing of large numbers of mostly younger male guest heroes with the older Batman, the brand encourages a “completist” approach toward consumption and a masculine style of play. Implications for the future of children’s entertainment in a world of corporate media are discussed. Introduction In 1955 the U.S. comic book publisher DC Comics premiered The Brave and The Bold, initially an adventure book featuring knights and Vikings (Daniels, 1999). Eventually the title showcased DC’s many superhero characters such as Hawkman, Wonder Woman and the Justice League of America. The comic shifted its focus to Batman beginning in 1966, with each issue pairing him with another DC superhero, often a "second-tier" character such as The Creeper or Deadman, as they battled different supervillains. -

Previewsworld.Com

PREVIEWSworld.com PAGE 1 of 4 JAN NEW RELEASES 2018 17 Every week, PREVIEWSworld announces which comics, graphic novels, toys and other pop-culture merchandise arriving at your local comic shop. The products will be on sale in comic shops on the indicated date. This list is tentative and subject to change. Please check with your retailer for availability. ITEM CODE TITLE PRICE ITEM CODE TITLE PRICE PREMIER PUBLISHERS DC COMICS/DC COLLECTIBLES c JUL170500 BATMAN BLACK & WHITE STATUE BY JOHN ROMITA JR $80.00 DARK HORSE COMICS IDW PUBLISHING c SEP170065 DEPT H HC VOL 03 DECOMPRESSED $19.99 c NOV170014 JENNY FINN #3 (OF 4) $3.99 c NOV170530 ASSASSINISTAS #2 CVR A HERNANDEZ (MR) $3.99 c SEP170087 LEGEND OF KORRA TP VOL 02 TURF WARS PT 2 $10.99 c NOV170531 ASSASSINISTAS #2 CVR B MCGEE (MR) $3.99 c SEP170093 MASS EFFECT DISCOVERY TP $17.99 c AUG170508 DIABLO HOUSE #3 CVR A SANTIPEREZ $3.99 c SEP170040 SHADOWS ON THE GRAVE HC $19.99 c AUG170509 DIABLO HOUSE #3 CVR B DICKINSON $3.99 c AUG170533 DIRK GENTLY EVERYTHING IS CONNECTED GAME $29.99 DC COMICS c OCT170530 FOUR WOMEN TP $17.99 c AUG170497 GENE COLAN TOMB OF DRACULA ARTIST ED HC $125.00 c OCT170362 ANARKY THE COMPLETE COLLECTION TP $19.99 c SEP170598 JUNGLE JOUST GAME $29.99 c NOV170223 AQUAMAN #32 $3.99 c SEP170482 LIGHTS OF THE AMALOU TP $39.99 c NOV170224 AQUAMAN #32 VAR ED $3.99 c DEC150527 MAXX MAXXIMIZED LTD ED HC VOL 02 PI c NOV170233 BATMAN #39 $2.99 c NOV170502 OPTIMUS PRIME #15 CVR A ZAMA $3.99 c NOV170234 BATMAN #39 VAR ED $2.99 c NOV170503 OPTIMUS PRIME #15 CVR B COLLER $3.99