Uba-Foundation-Fine-Boys.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yoruba Art Music: Fronting the Progenitors ______

African Musicology Online Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 19-44, 2018 YORUBA ART MUSIC: FRONTING THE PROGENITORS __________________________ Ade Oluwa Okunade1; Onyee Nwankpa2 Department of Music, University of Port Harcourt, Port Harcourt, Nigeria *Corresponding Author Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT The bedrock of music genres in Africa today remains the traditional music. The western formal music education embraced by African schools during and after the scramble for Africa by the northern hemisphere has given ‘colorations’ to music genres both in the classroom and the larger society. Its legacies are found more in popular music. The most interesting thing is that essence of music remains undaunted in the faces of all new formalities in the educational system. Music still lives on stage and not on paper. This paper emerges as a derivative of the Yoruba Art Music (YAM) festival premiered in 2015 at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria. With bibliographical evidences and substantial interaction with a non-Yoruba speaking music scholar this paper sufficed that the YAM festival is worth doing and is capable of solving other attendant issues in music scholarship. Key Words: Yoruba art music, Traditional, Legacies, Music education, Popular music. INTRODUCTION The missionary who came to Nigeria in the 19th century came through the Yoruba land, in the Southwestern Nigeria. This gave early rise to western formal education in the area, of which music education was paramount. The Yoruba Art Music (YAM) festival emerged in 2015 with the concept of having discourse of what constitutes art music followed by stage production of Yoruba musical works. The authors involved non-Yoruba speaking scholars having in mind the conventional traits in African music, and only wanted to bring out the traits that point out identities from one region to another, to take part especially in the discourse. -

THE AESTHETICS of IGBO MASK THEATRE by VICTOR

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 1996 The composite scene: the aesthetics of Igbo mask theatre Ukaegbu, Victor Ikechukwu http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/2811 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. THE COMPOSITE SCENE: THE AESTHETICS OF IGBO MASK THEATRE by VICTOR IKECHUKWU UKAEGBU A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfilment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Exeter School of Arts and Design Faculty of Arts and Education University of Plymouth May 1996. 90 0190329 2 11111 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT. This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author's prior written consent. Date .. 3.... M.~~J. ... ~4:l~.:. VICTOR I. UKAEGBU. ii I 1 Unlversity ~of Plymouth .LibratY I I 'I JtemNo q jq . .. I I . · 00 . '()3''2,;lfi2. j I . •• - I '" Shelfmiul(: ' I' ~"'ro~iTHESIS ~2A)2;~ l)f(lr ' ' :1 ' I . I Thesis Abstract THE COMPOSITE SCENE: THE AESTHETICS OF IGBO MASK THEATRE by VICTOR IKECHUKWU UKAEGBU An observation of mask performances in Igboland in South-Eastern Nigeria reveals distinctions among displays from various communities. -

Press Contacts: Michael Krause | Foundry Communications | (212) 586-7967 | [email protected]

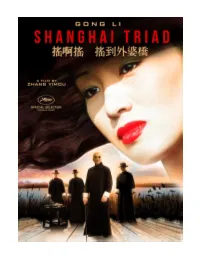

presents a film by ZHANG YIMOU starring GONG LI LI BAOTIAN LI XUEJIAN SUN CHUN WANG XIAOXIAO ————————————————————— “Visually sumptuous…unforgettable.” –New York Post “Crime drama has rarely been this gorgeously alluring – or this brutal.” –Entertainment Weekly ————————————————————— 1995 | France, China | Mandarin with English subtitles | 108 minutes 1.85:1 Widescreen | 2.0 Stereo Rated R for some language and images of violence DIGITALLY RESTORED Press Contacts: Michael Krause | Foundry Communications | (212) 586-7967 | [email protected] Film Movement Booking Contacts: Jimmy Weaver | Theatrical | (216) 704-0748 | [email protected] Maxwell Wolkin | Festivals & Non-Theatrical | (212) 941-7744 x211 | [email protected] SYNOPSIS Hired to be a servant to pampered nightclub singer and mob moll Xiao Jinbao (Gong Li), naive teenager Shuisheng (Wang Xiaoxiao) is thrust into the glamorous and deadly demimonde of 1930s Shanghai. Over the course of seven days, Shuisheng observes mounting tensions as triad boss Tang (Li Baotian) begins to suspect traitors amongst his ranks and rivals for Xiao Jinbao’s affections. STORY Shanghai, 1930. Mr. Tang (Li Boatian), the godfather of the Tang family-run Green dynasty, is the city’s overlord. Having allied himself with Chiang Kai-shek and participated in the 1927 massacre of the Communists, he controls the opium and prostitution trade. He has also acquired the services of Xiao Jinbao (Gong Li), the most beautiful singer in Shanghai. The story of Shanghai Triad is told from the point of view of a fourteen-year-old boy, Shuisheng (Wang Xiaoxiao), whose uncle has brought him into the Tang Brotherhood. His job is to attend to Xiao Jinbao. -

I Cento Passi (The Hundred Steps, 2000) Is Giordana's Biopic About Giuseppe 'Peppino' Impastato, a Leftist Anti-Mafia Activist Murdered in Sicily in 1978

33 Marco Tullio Giordana' s The Hundred Steps: The Biopic as Political Cinema GEORGE DE STEFANO During the 1980s, the political engagement that fuelled much of Italy's postwar realist cinema nearly vanished, a casualty of both the domin ance of television and the decline of the political Left. The generation of great postwar auteurs - Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica, Federico Fellini, and Pier Paolo Pasolini - had disappeared. Their departure, notes Millicent Marcus, was followed by 'the waning of the ideological and generic impulses that fueled the revolutionary achievement of their successors: Rosi, Petri, Bertolucci, Bellocchio, Ferreri, the Tavianis, Wertmuller, Cavani, and Scola.' 1 The decline of political cinema was inextricable from the declining fortunes of the Left following the vio lent extremism of the 1970s, the so-called leaden years and, a decade later, the fall of Communism. The waning of engage cinema continued throughout the 1990s, with a few exceptions. But as the twentieth cen tury drew to a close, the director Marco Tullio Giordana made a film that represented a return to the tradition of political commitment. I cento passi (The Hundred Steps, 2000) is Giordana's biopic about Giuseppe 'Peppino' Impastato, a leftist anti-Mafia activist murdered in Sicily in 1978. The film was critically acclaimed, winning the best script award at the Venice Film Festival and acting awards for two of its stars. It was a box office success in Italy, with its popularity extending beyond the movie theatres. Giordana's film, screened in schools and civic as sociations throughout Sicily, became a consciousness-raising tool for anti-Mafia forces, as well as a memorial to a fallen leader of the anti Mafia struggle. -

Thatcher Alle Corde Sgrida Martelli Eliache Svanisce La Minaccia Militare

Giornale + Salvagente L. 1500 Giornale Anno 67°, n. 105 Spedizione m abb. post. gr. 1/70 del Partito arretrati L. 3300 comunista T'Unita italiano 5 maggio 1990 La dottrina Bush: «Una Nato I laburisti col 43% (+11%) sorpassano i conservatori (31%) che perdono 12 punti Bobbio e Occhietto perplessi più politica* Avanzata tory solo in alcuni distretti londinesi. Annunciato un minirimpasto di governo sul verdetto contro Loto continua «C li Stati Uniti devono restare una potenza europea nel sen- sc più ampio, dal punto di vista politico, militare ed econo mici:». Bush (nella foto) teme che gli Usa vengano tagliati fuori dal processo di unificazione europea, per questo rilan- Andreotti cii II vertice "costituente»della Nato, in programma perfine pijgno. L'Alleanza atlantica - dice il presidente - deve •prendere in considerazione la sua futura missione politica» Thatcher alle corde sgrida Martelli eliache svanisce la minaccia militare. A PAGINA 5 In autostrada Ci si avvia alla fine delle lun ghe ed estenuami code nei con il Telepass caselli delle autostrade? Da sul caso Sofri peir evitare lunedi sull'Autosole, a Mila La destra battuta nel suo «tempio» no, a Roma e a Napoli, in via li! lunghe code sperimentale, va in funzione il Telepass, un sistema tele Per i conservatori è stato un autentico tracollo. Martelli sconfessalo da Andreotti. Sul caso Sofri scen malico che consente all'au- C'è anche Nelle amministrative di giovedì i tories sono calati de in campo il presidente del Consiglio per criticare il tcmobilista di entrare ed uscire senza fermare il veicolo. Il del 12% rispetto al risultato ottenuto nelle ultime suo vice e polemizzare con «quel mondo culturale percorso ed il pedaggio viene registrato attraverso un appa elezioni politiche tre anni fa. -

Journal of Film Preservation Director and Curator, Národní Filmov´Y Archiv (Montréal) (Praha)

Journal of Film Preservation Contributors to this issue... Ont collaboré à ce numéro... Journal Han participado en este número... 73 04/2007 ANTTI ALANEN of Film Head of the FIAF Programming and Access to KAE ISHIHARA Collections Commission, Programmer at the Finnish Film Archive Film archivist, Head of Film Preservation Society (Helsinki) (Tokyo) Preservation RENÉ BEAUCLAIR JEANICK LE NAOUR Directeur de la Médiathèque Guy L. Côté, Responsable de la Cinémathèque Afrique (Paris) Cinémathèque québécoise (Montréal) ÉRIC LE ROY EILEEN BOWSER Chef du Service accès, valorisation et Film historian, Honorary Member of FIAF (New enrichissement des collections, Archives York) françaises du film-CNC (Bois d’Arcy) PAOLO CHERCHI USAI PATRICK LOUGHNEY Director, National Film and Sound Archive Senior Curator, George Eastman House - Motion (Canberra) Picture Department (Rochester) Revista de la Federación Internacional de Archivos Fílmicos JOSÉ MANUEL COSTA NWANNEKA OKONKWO Film archivist, Cinemateca portuguesa / Museo Head of the do cinema (Lisbon) National Film Video and Sound Archive (Jos) ROBERT DAUDELIN VLADIMIR OPELA Rédacteur en chef du Journal of Film Preservation Director and Curator, Národní Filmov´y Archiv (Montréal) (Praha) MARCO DE BLOIS PAULO EMILIO SALLES GOMES the by Published International Federation of Film Archives Conservateur cinéma d’animation, Film scholar and archivist (1929 -1977) (São Cinémathèque québécoise (Montréal) Paulo) CHRISTIAN DIMITRIU ROGER SMITHER Éditeur et membre du comité de rédaction du Keeper, Film and Video -

Absent Presence: Women in American Gangster Narrative

Absent Presence: Women in American Gangster Narrative Carmela Coccimiglio Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a doctoral degree in English Literature Department of English Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Carmela Coccimiglio, Ottawa, Canada, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract iii Acknowledgements v Introduction 1 Chapter One 27 “Senza Mamma”: Mothers, Stereotypes, and Self-Empowerment Chapter Two 57 “Three Corners Road”: Molls and Triangular Relationship Structures Chapter Three 90 “[M]arriage and our thing don’t jive”: Wives and the Precarious Balance of the Marital Union Chapter Four 126 “[Y]ou have to fucking deal with me”: Female Gangsters and Textual Outcomes Chapter Five 159 “I’m a bitch with a gun”: African-American Female Gangsters and the Intersection of Race, Sexual Orientation, and Gender Conclusion 186 Works Cited 193 iii ABSTRACT Absent Presence: Women in American Gangster Narrative investigates women characters in American gangster narratives through the principal roles accorded to them. It argues that women in these texts function as an “absent presence,” by which I mean that they are a convention of the patriarchal gangster landscape and often with little import while at the same time they cultivate resistant strategies from within this backgrounded positioning. Whereas previous scholarly work on gangster texts has identified how women are characterized as stereotypes, this dissertation argues that women characters frequently employ the marginal positions to which they are relegated for empowering effect. This dissertation begins by surveying existing gangster scholarship. There is a preoccupation with male characters in this work, as is the case in most gangster texts themselves. -

Copyright by Amanda Rose Bush 2019

Copyright by Amanda Rose Bush 2019 The Dissertation Committee for Amanda Rose Bush Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Dissertation: Self-presentation, Representation, and a Reconsideration of Cosa nostra through the Expanding Narratives of Tommaso Buscetta Committee: Paola Bonifazio, Supervisor Daniela Bini Circe Sturm Alessandra Montalbano Self-presentation, Representation, and a Reconsideration of Cosa nostra through the Expanding Narratives of Tommaso by Amanda Rose Bush Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2019 Dedication I dedicate this disseration to Phoebe, my big sister and biggest supporter. Your fierce intelligence and fearless pursuit of knowledge, adventure, and happiness have inspired me more than you will ever know, as individual and as scholar. Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been possible without the sage support of Professor Paola Bonifazio, who was always open to discussing my ideas and provided both encouragement and logistical prowess for my research between Corleone, Rome, Florence, and Bologna, Italy. Likewise, she provided a safe space for meetings at UT and has always framed her questions and critiques in a manner which supported my own analytical development. I also want to acknowledge and thank Professor Daniela Bini whose extensive knowledge of Sicilian literature and film provided many exciting discussions in her office. Her guidance helped me greatly in both the genesis of this project and in understanding its vaster implications in our hypermediated society. Additionally, I would like to thank Professor Circe Sturm and Professor Alessandra Montalbano for their very important insights and unique academic backgrounds that helped me to consider points of connection of this project to other larger theories and concepts. -

L'italiano Al Cinema, L'italiano Del Cinema

spacca LA LINGUA ITALIANA NEL MONDO Nuova serie e-book L’ebook è molto di + Seguici su facebook, twitter, ebook extra spacca © 2017 Accademia della Crusca, Firenze – goWare, Firenze ISBN 978-88-6797-874-8 LA LINGUA ITALIANA NEL MONDO. Nuova serie e-book Nessuna parte del libro può essere riprodotta in qualsiasi forma o con qualsiasi mezzo senza l’autorizzazione dei proprietari dei diritti e dell’editore. Accademia della Crusca Via di Castello 46 – 50141 Firenze +39 055 454277/8 – Fax +39 055 454279 Sito: www.accademiadellacrusca.it Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/AccademiaCrusca Twitter: https://twitter.com/AccademiaCrusca YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/user/AccademiaCrusca Contatti: http://www.accademiadellacrusca.it/it/contatta-la-crusca goWare è una startup fiorentina specializzata in nuova editoria Fateci avere i vostri commenti a: [email protected] Blogger e giornalisti possono richiedere una copia saggio a Maria Ranieri: [email protected] Redazione a cura di Dalila Bachis Copertina: Lorenzo Puliti Premessa La storia della lingua italiana del Novecento è legata a quella del cinema a doppio no- do: inscenando dapprima l’italiano letterario nelle didascalie del muto e nei dialoghi d’ascendenza teatrale del primo sonoro, per poi dar voce sempre più spesso a tutte le varietà d’Italia, lo schermo, più che da diaframma, ha fatto da mezzo di continuo in- terscambio tra usi reali e riprodotti. Lo testimonia, tuttora, la ricca messe di “filmismi” nell’italiano di tutti i giorni, da quarto potere all’attimo fuggente, dall’Armata Branca- leone alla grande abbuffata, alcuni dei quali migrati addirittura in molte altre lingue del mondo, come i fellinismi dolcevita e paparazzo. -

Biafran Separatists

Country Policy and Information Note Nigeria: Biafran separatists Version 1.0 April 2020 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies: x A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm x The general humanitarian situation is so severe as to breach Article 15(b) of European Council Directive 2004/83/EC (the Qualification Directive) / Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules x The security situation presents a real risk to a civilian’s life or person such that it would breach Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules x A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) x A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory x A claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and x If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. -

Valid Journal.Cdr

179 180 The Development Of Indigenous African Dance: A Paradigmatic ... THE DEVELOPMENT OF INDIGENOUS AFRICAN of Africans from cradle to grave (Iyeh 20). A dancer is a DANCE: A PARADIGMATIC APPRAISAL OF NKPOKITI communicator. He communicates with the audience through OF UMUNZE. his body. The amount of appreciation accrued to a dancer depends on his level of communication during performance. Ofobuike Nwafor The human body speaks a number of languages varying from what we do with the body to how we employ the space and Abstract native elements around us. The body provides good source of A typical African society is characterized by indigenous unscripted message outside speech (Anne 94). performances that embody the cultural attributes of the people. These Dance is also believed to be the outward rhythmic performances are often structured in the form of dance and are used to expression of emotion. These emotion are expressed to the mark significant events in the community. Dance being a performing delight and understanding of the people. Nwaozuzu believes art has the tendency and potency to evolve and take a new form inline that dance is more than a mere aesthetic diversion but a with the socio-cultural changes of the society, and this evolution has therapeutic ritual and the expression of life's emotion (23). come to be known as dance development. Dance development is the Traditional dances are highly spiritual extension of human different stages of evolution a dance has undergone to get to its experiences and express realities (Udoka 228). Unlike that of present stage. It is those changes that occurred in a dance, and are conservative Europeans, Africans dances especially that of often caused by some factors. -

Hoods and Yakuza the Shared Myth of the American and Japanese Gangster Film

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Hoods and Yakuza The Shared Myth of the American and Japanese Gangster Film. Pate, Simon The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author For additional information about this publication click this link. http://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/xmlui/handle/123456789/13034 Information about this research object was correct at the time of download; we occasionally make corrections to records, please therefore check the published record when citing. For more information contact [email protected] Hoods and Yakuza: the Shared Myth of the American and Japanese Gangster Film 1 Hoods and Yakuza The Shared Myth of the American and Japanese Gangster Film by Simon Pate Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Languages, Linguistics and Film Queen Mary University of London March 2016 Hoods and Yakuza: the Shared Myth of the American and Japanese Gangster Film 2 Statement of Originality I, Simon Pate, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material.