A Case Study of Igbo Bongo Musicians, South-Eastern Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

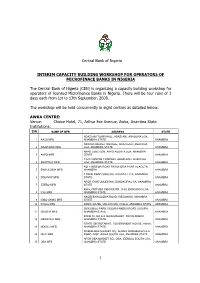

Interim Capacity Building for Operators of Microfinance Banks

Central Bank of Nigeria INTERIM CAPACITY BUILDING WORKSHOP FOR OPERATORS OF MICROFINACE BANKS IN NIGERIA The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) is organizing a capacity building workshop for operators of licensed Microfinance Banks in Nigeria. There will be four runs of 3 days each from 1st to 13th September, 2008. The workshop will be held concurrently in eight centres as detailed below: AWKA CENTRE: Venue: Choice Hotel, 71, Arthur Eze Avenue, Awka, Anambra State. Institutions: S/N NAME OF MFB ADDRESS STATE ADAZI ANI TOWN HALL, ADAZI ANI, ANAOCHA LGA, 1 AACB MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NKWOR MARKET SQUARE, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 2 ADAZI-ENU MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA AKPO JUNCTION, AKPO AGUATA LGA, ANAMBRA 3 AKPO MFB STATE ANAMBRA CIVIC CENTRE COMPLEX, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 4 BESTWAY MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NO 1 MISSION ROAD EKWULOBIA P.M.B.24 AGUTA, 5 EKWULOBIA MFB ANAMBRA ANAMBRA 1 BANK ROAD UMUCHU, AGUATA L.G.A, ANAMBRA 6 EQUINOX MFB STATE ANAMBRA AFOR IGWE UMUDIOKA, DUNUKOFIA LGA, ANAMBRA 7 EZEBO MFB STATE ANAMBRA KM 6, ONITHSA OKIGWE RD., ICHI, EKWUSIGO LGA, 8 ICHI MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NNOBI/EKWULOBIA ROAD, IGBOUKWU, ANAMBRA 9 IGBO-UKWU MFB STATE ANAMBRA 10 IHIALA MFB BANK HOUSE, ORLU ROAD, IHIALA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA EKWUSIGO PARK, ISUOFIA-NNEWI ROAD, ISUOFIA, 11 ISUOFIA MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA ZONE 16, NO.6-9, MAIN MARKET, NKWO-NNEWI, 12 MBAWULU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA STATE SECRETARIAT, GOVERNMENT HOUSE, AWKA, 13 NDIOLU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NGENE-OKA MARKET SQ., ALONG AMAWBIA/AGULU 14 NICE MFB ROAD, NISE, AWKA SOUTH -

The African Belief System and the Patient's Choice of Treatment From

Case Report iMedPub Journals ACTA PSYCHOPATHOLOGICA 2017 www.imedpub.com ISSN 2469-6676 Vol. 3 No. 4: 49 DOI: 10.4172/2469-6676.100121 The African Belief System and the Patient’s Mavis Asare1* and 2 Choice of Treatment from Existing Health Samuel A Danquah Models: The Case of Ghana 1 Methodist University College Ghana, Progressive Life Center, Ghana 2 Psychology Department, Legon/ Methodist University College Ghana, Ghana Abstract This paper presents a narrative review including a case study of the African Belief System. A strong belief in supernatural powers is deeply rooted in the African *Corresponding author: culture. In Ghana, there is a spiritual involvement in the treatment of illness Mavis Asare and healthcare. The new health model in the African culture therefore can be considered to be the Biopsychosocial(s) model-with the s representing spiritual [email protected] practice-compared to the biopsychosocial model in Western culture. The case study on dissociative amnesia illustrates that Africans consider spiritual causes of Methodist University College Ghana/ illness when a diagnosis of an illness is very challenging. The causes of mental Progressive Life Center, P.O. Box AN 5628, health conditions in particular seem challenging to Africans, and therefore are Accra-North, Ghana. easily attributed to spiritual powers. The spiritual belief in African clients should not be rejected but should be used by caregivers to guide and facilitate clients’ Tel: +233 263344272 recovery from illness. The spiritual belief provides hope. Therefore when combined with Western treatment, this belief can quicken illness recovery. Keywords: Spiritual belief; Spiritual; African; Traditional culture; Biopsychosocial; Citation: Asare M, Danquah SA (2017) The Treatment methods; Mental health African Belief System and the Patient’s Choice of Treatment from Existing Health Models: The Case of Ghana. -

Culture, Power and Resistance Refl Ections on the Ideas of Amilcar Cabral – Firoze Manji Introduction

STATE OF POWER 2017 Culture, power and resistance refl ections on the ideas of Amilcar Cabral – Firoze Manji Introduction Amilcar Cabral and Frantz Fanon1 are among the most important thinkers from Africa on the politics of liberation and emancipation. While the relevance of Fanon’s thinking has re-emerged, with popular movements such as Abahlali baseMjondolo in South Africa proclaiming his ideas as the inspiration for their mobilizations, as well as works by Sekyi-Otu, Alice Cherki, Nigel Gibson, Lewis Gordon and others, Cabral’s ideas have not received as much attention. Cabral was the founder and leader of the Guinea-Bissau and Cabo Verde liberation movement, Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde (PAIGC). He was a revolutionary, humanist, poet, military strategist, and prolific writer on revolutionary theory, culture and liberation. The struggles he led against Portuguese colonialism contributed to the collapse not only of Portugal’s African empire, but also to the downfall of the fascist dictatorship in Portugal and to the Portuguese revolution of 1974/5, events that he was not to witness: he was assassinated by some of his comrades, with the support of the Portuguese secret police, PIDE, on 20 January 1973. By the time of his death, two thirds of Guinea was in the liberated zones, where popular democratic structures were established that would form the basis for the future society: women played political and military leadership roles, the Portuguese currency was banned and replaced by barter, agricultural production was devoted to the needs of the population, and many of the elements of a society based For Cabral, and also for Fanon, on humanity, equality and justice began to emerge organically through popular debate and discussion. -

Okanga Royal Drum: the Dance for the Prestige and Initiates Projecting Igbo Traditional Religion Through Ovala Festival in Aguleri Cosmolgy

Global Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Vol.8, No. 3, pp.19-49, March 2020 Published by ECRTD-UK Print ISSN: 2052-6350(Print), Online ISSN: 2052-6369(Online) OKANGA ROYAL DRUM: THE DANCE FOR THE PRESTIGE AND INITIATES PROJECTING IGBO TRADITIONAL RELIGION THROUGH OVALA FESTIVAL IN AGULERI COSMOLGY Madukasi Francis Chuks, PhD ChukwuemekaOdumegwuOjukwu University, Department of Religion & Society. Igbariam Campus, Anambra State, Nigeria. PMB 6059 General Post Office Awka. Anambra State, Nigeria. Phone Number: +2348035157541. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT: No literature I have found has discussed the Okanga royal drum and its elements of an ensemble. Elaborate designs and complex compositional ritual functions of the traditional drum are much encountered in the ritual dance culture of the Aguleri people of Igbo origin of South-eastern Nigeria. This paper explores a unique type of drum with mystifying ritual dance in Omambala river basin of the Igbo—its compositional features and specialized indigenous style of dancing. Oral tradition has it that the Okanga drum and its style of dance in which it figures originated in Aguleri – “a farming/fishing Igbo community on Omambala River basin of South- Eastern Nigeria” (Nzewi, 2000:25). It was Eze Akwuba Idigo [Ogalagidi 1] who established the Okanga royal band and popularized the Ovala festival in Igbo land equally. Today, due to that syndrome and philosophy of what I can describe as ‘Igbo Enwe Eze’—Igbo does not have a King, many Igbo traditional rulers attend Aguleri Ovala festival to learn how to organize one in their various communities. The ritual festival of Ovala where the Okanga royal drum features most prominently is a commemoration of ancestor festival which symbolizes kingship and acts as a spiritual conduit that binds or compensates the communities that constitutes Eri kingdom through the mediation for the loss of their contact with their ancestral home and with the built/support in religious rituals and cultural security of their extended brotherhood. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Igbo Man's Belief in Prayer for the Betterment of Life Ikechukwu

Igbo man’s Belief in Prayer for the Betterment of Life Ikechukwu Okodo African & Asian Studies Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka Abstract The Igbo man believes in Chukwu strongly. The Igbo man expects all he needs for the betterment of his life from Chukwu. He worships Chukwu traditionally. His religion, the African Traditional Religion, was existing before the white man came to the Igbo land of Nigeria with his Christianity. The Igbo man believes that he achieves a lot by praying to Chukwu. It is by prayer that he asks for the good things of life. He believes that prayer has enough efficacy to elicit mercy from Chukwu. This paper shows that the Igbo man, to a large extent, believes that his prayer contributes in making life better for him. It also makes it clear that he says different kinds of prayer that are spontaneous or planned, private or public. Introduction Since the Igbo man believes in Chukwu (God), he cannot help worshipping him because he has to relate with the great Being that made him. He has to sanctify himself in order to find favour in Chukwu. He has to obey the laws of his land. He keeps off from blood. He must not spill blood otherwise he cannot stand before Chukwu to ask for favour and succeed. In spite of that it can cause him some ill health as the Igbo people say that those whose hands are bloody are under curses which affect their destines. The Igboman purifies himself by avoiding sins that will bring about abominations on the land. -

Karaoke Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #9 Dream Lennon, John 1985 Bowling For Soup (Day Oh) The Banana Belefonte, Harry 1994 Aldean, Jason Boat Song 1999 Prince (I Would Do) Anything Meat Loaf 19th Nervous Rolling Stones, The For Love Breakdown (Kissed You) Gloriana 2 Become 1 Jewel Goodnight 2 Become 1 Spice Girls (Meet) The Flintstones B52's, The 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The (Reach Up For The) Duran Duran 2 Faced Louise Sunrise 2 For The Show Trooper (Sitting On The) Dock Redding, Otis 2 Hearts Minogue, Kylie Of The Bay 2 In The Morning New Kids On The (There's Gotta Be) Orrico, Stacie Block More To Life 2 Step Dj Unk (Your Love Has Lifted Shelton, Ricky Van Me) Higher And 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc Higher 2001 Space Odyssey Presley, Elvis 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 24 Jem (M-F Mix) 24 7 Edmonds, Kevon 1 Thing Amerie 24 Hours At A Time Tucker, Marshall, 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) Plain White T's Band 1,000 Faces Montana, Randy 24's Richgirl & Bun B 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys 25 Miles Starr, Edwin 100 Years Five For Fighting 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The 10th Ave Freeze Out Springsteen, Bruce 26 Miles Four Preps, The 123 Estefan, Gloria 3 Spears, Britney 1-2-3 Berry, Len 3 Dressed Up As A 9 Trooper 1-2-3 Estefan, Gloria 3 Libras Perfect Circle, A 1234 Feist 300 Am Matchbox 20 1251 Strokes, The 37 Stitches Drowning Pool 13 Is Uninvited Morissette, Alanis 4 Minutes Avant 15 Minutes Atkins, Rodney 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin 15 Minutes Of Shame Cook, Kristy Lee Timberlake 16 @ War Karina 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake & 16th Avenue Dalton, Lacy J. -

Halifu Osumare, the Hiplife in Ghana: West Africa Indigenization of Hip-Hop, New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, 219 Pp., $85.00 (Hardcover)

International Journal of Communication 7 (2013), Book Review 1501–1504 1932–8036/2013BKR0009 Halifu Osumare, The Hiplife in Ghana: West Africa Indigenization of Hip-Hop, New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, 219 pp., $85.00 (hardcover). Reviewed by Angela Anima-Korang Southern Illinois University Carbondale Ghana’s music industry can be described as a thriving one, much like its film industry. The West African sovereign state is well on its way to becoming a force to reckon with on the international music market. With such contemporary rap artists as Sarkodie, Fuse ODG (Azonto), Reggie Rockstone, R2Bs, and Edem in its fold, Ghana’s music is transcending borders and penetrating international markets. Historically, Ghana’s varying ethnic groups, as well as its interaction with countries on the continent, greatly influences the genres of music that the country has created over the years. Traditionally, Ghana’s music is geographically categorized by the types of musical instruments used: Music originating from the North uses stringed instruments and high-pitched voices; and music emanating from the Coast features drums and relatively low-pitched voice intermissions. Up until the 1990s, “highlife” was the most popular form of music in Ghana, borrowing from jazz, swing, rock, soukous, and mostly music to which the colonizers had listened. Highlife switched from the traditional form with drums to a music genre characterized by the electric guitar. “Burger-highlife” then erupted as a form of highlife generated by artists who had settled out of Ghana (primarily in Germany), but who still felt connected to the motherland through music, such as Ben Brako, George Darko, and Pat Thomas. -

African Drumming in Drum Circles by Robert J

African Drumming in Drum Circles By Robert J. Damm Although there is a clear distinction between African drum ensembles that learn a repertoire of traditional dance rhythms of West Africa and a drum circle that plays primarily freestyle, in-the-moment music, there are times when it might be valuable to share African drumming concepts in a drum circle. In his 2011 Percussive Notes article “Interactive Drumming: Using the power of rhythm to unite and inspire,” Kalani defined drum circles, drum ensembles, and drum classes. Drum circles are “improvisational experiences, aimed at having fun in an inclusive setting. They don’t require of the participants any specific musical knowledge or skills, and the music is co-created in the moment. The main idea is that anyone is free to join and express himself or herself in any way that positively contributes to the music.” By contrast, drum classes are “a means to learn musical skills. The goal is to develop one’s drumming skills in order to enhance one’s enjoyment and appreciation of music. Students often start with classes and then move on to join ensembles, thereby further developing their skills.” Drum ensembles are “often organized around specific musical genres, such as contemporary or folkloric music of a specific culture” (Kalani, p. 72). Robert Damm: It may be beneficial for a drum circle facilitator to introduce elements of African music for the sake of enhancing the musical skills, cultural knowledge, and social experience of the participants. PERCUSSIVE NOTES 8 JULY 2017 PERCUSSIVE NOTES 9 JULY 2017 cknowledging these distinctions, it may be beneficial for a drum circle facilitator to introduce elements of African music (culturally specific rhythms, processes, and concepts) for the sake of enhancing the musi- cal skills, cultural knowledge, and social experience Aof the participants in a drum circle. -

Proceedings Geological Society of London

Downloaded from http://jgslegacy.lyellcollection.org/ at University of California-San Diego on February 18, 2016 PROCEEDINGS OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON. SESSION 1884-851 November 5, 1884. Prof. T. G. Bo~sEY, D.Sc., LL.D., F.R.S., President, in the Chair. William Lower Carter, Esq., B.A., Emmanuel College, Cambridge, was elected a Fellow of the Society. The SECRETARYaunouneed.bhat a water-colour picture of the Hot Springs of Gardiner's River, Yellowstone Park, Wyoming Territory, U.S.A., which was painted on the spot by Thomas Moran, Esq., had been presented to the Society by the artist and A. G. Re"::~aw, Esq., F.G.S. The List of Donations to the Library was read. The following communications were read :-- 1. "On a new Deposit of Pliocene Age at St. Erth, 15 miles east of the Land's End, Cornwall." By S. V. Wood, Esq., F.G.S. 2. "The Cretaceous Beds at Black Ven, near Lyme Regis, with some supplementary remarks on the Blackdown Beds." By the Rev. W. Downes, B.A., F.G.S. 3. "On some Recent Discoveries in the Submerged Forest of Torbay." By D. Pidgeon, Esq., F.G.S. The following specimens were exhibited :- Specimens exhibited by Searles V. Wood, Esq., the Rev. W. Downes, B.A., and D. Pidgeon, Esq., in illustration of their papers. a Downloaded from http://jgslegacy.lyellcollection.org/ at University of California-San Diego on February 18, 2016 PROCEEDINGS OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY. A worked Flint from the Gravel-beds (? Pleistocene) in the Valley of the Tomb of the Kings, near Luxor (Thebes), Egypt, ex- hibited by John E. -

Community's Influence on Igbo Musical Artiste and His

International Journal of Literature and Arts 2019; 7(1): 1-8 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ijla doi: 10.11648/j.ijla.20190701.11 ISSN: 2331-0553 (Print); ISSN: 2331-057X (Online) Community’s Influence on Igbo Musical Artiste and His Art Alvan-Ikoku Okwudiri Nwamara Department of Music, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria Email address: To cite this article: Alvan-Ikoku Okwudiri Nwamara. Community’s Influence on Igbo Musical Artiste and His Art. International Journal of Literature and Arts . Vol. 7, No. 1, 2019, pp. 1-8. doi: 10.11648/j.ijla.20190701.11 Received : September 19, 2018; Accepted : October 17, 2018; Published : March 11, 2019 Abstract: The Igbo traditional concept of “Ohaka: The Community is Supreme,” is mostly expressed in Igbo names like; Nwoha/Nwora (Community-Owned Child), Oranekwulu/Ohanekwulu (Community Intercedes/intervenes), Obiora/Obioha (Community-Owned Son), Adaora/Adaoha (Community-Owned Daughter) etc. This indicates value attached to Ora/Oha (Community) in Igbo culture. Musical studies have shown that the Igbo musical artiste does not exist in isolation; rather, he performs in/for his community and is guided by the norms and values of his culture. Most Igbo musicological scholars affirm that some of his works require the community as co-performers while some require collaboration with some gifted members of his community. His musical instruments are approved and often times constructed by members of his community as well as his costumes and other paraphernalia. But in recent times, modernity has not been so friendly to this “Ohaka” concept; hence the promotion of individuality/individualism concepts in various guises within the context of Igbo musical arts performance. -

Explore Music 7 World Drumming.Pdf (PDF 2.11

Explore Music 7: World Drumming Explore Music 7: World Drumming (Revised 2020) Page 1 Explore Music 7: World Drumming (Revised 2020) Page 2 Contents Explore Music 7: World Drumming Overview ........................................................................................................................................5 Unit 1: The Roots of Drumming (4-5 hours)..................................................................................7 Unit 2: Drum Circles (8-10 hours) .................................................................................................14 Unit 3: Ensemble Playing (11-14 hours) ........................................................................................32 Supporting Materials.......................................................................................................................50 References.................................................. ....................................................................................69 The instructional hours indicated for each unit provide guidelines for planning, rather than strict requirements. The sequence of skill and concept development is to be the focus of concern. Teachers are encouraged to adapt these suggested timelines to meet the needs of their students. To be effective in teaching this module, it is important to use the material contained in Explore Music: Curriculum Framework and Explore Music: Appendices. Therefore, it is recommended that these two components be frequently referenced to support the suggestions for