Égwú Ŕmŕlŕ: Women in Traditional Performing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

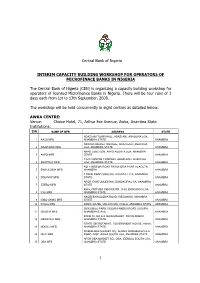

Interim Capacity Building for Operators of Microfinance Banks

Central Bank of Nigeria INTERIM CAPACITY BUILDING WORKSHOP FOR OPERATORS OF MICROFINACE BANKS IN NIGERIA The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) is organizing a capacity building workshop for operators of licensed Microfinance Banks in Nigeria. There will be four runs of 3 days each from 1st to 13th September, 2008. The workshop will be held concurrently in eight centres as detailed below: AWKA CENTRE: Venue: Choice Hotel, 71, Arthur Eze Avenue, Awka, Anambra State. Institutions: S/N NAME OF MFB ADDRESS STATE ADAZI ANI TOWN HALL, ADAZI ANI, ANAOCHA LGA, 1 AACB MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NKWOR MARKET SQUARE, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 2 ADAZI-ENU MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA AKPO JUNCTION, AKPO AGUATA LGA, ANAMBRA 3 AKPO MFB STATE ANAMBRA CIVIC CENTRE COMPLEX, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 4 BESTWAY MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NO 1 MISSION ROAD EKWULOBIA P.M.B.24 AGUTA, 5 EKWULOBIA MFB ANAMBRA ANAMBRA 1 BANK ROAD UMUCHU, AGUATA L.G.A, ANAMBRA 6 EQUINOX MFB STATE ANAMBRA AFOR IGWE UMUDIOKA, DUNUKOFIA LGA, ANAMBRA 7 EZEBO MFB STATE ANAMBRA KM 6, ONITHSA OKIGWE RD., ICHI, EKWUSIGO LGA, 8 ICHI MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NNOBI/EKWULOBIA ROAD, IGBOUKWU, ANAMBRA 9 IGBO-UKWU MFB STATE ANAMBRA 10 IHIALA MFB BANK HOUSE, ORLU ROAD, IHIALA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA EKWUSIGO PARK, ISUOFIA-NNEWI ROAD, ISUOFIA, 11 ISUOFIA MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA ZONE 16, NO.6-9, MAIN MARKET, NKWO-NNEWI, 12 MBAWULU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA STATE SECRETARIAT, GOVERNMENT HOUSE, AWKA, 13 NDIOLU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NGENE-OKA MARKET SQ., ALONG AMAWBIA/AGULU 14 NICE MFB ROAD, NISE, AWKA SOUTH -

Bible Translation and Language Elaboration: the Igbo Experience

Bible Translation and Language Elaboration: The Igbo Experience A thesis submitted to the Bayreuth International Graduate School of African Studies (BIGSAS), Universität Bayreuth, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Dr. Phil.) in English Linguistics By Uchenna Oyali Supervisor: PD Dr. Eric A. Anchimbe Mentor: Prof. Dr. Susanne Mühleisen Mentor: Prof. Dr. Eva Spies September 2018 i Dedication To Mma Ụsọ m Okwufie nwa eze… who made the journey easier and gave me the best gift ever and Dikeọgụ Egbe a na-agba anyanwụ who fought against every odd to stay with me and always gives me those smiles that make life more beautiful i Acknowledgements Otu onye adịghị azụ nwa. So say my Igbo people. One person does not raise a child. The same goes for this study. I owe its success to many beautiful hearts I met before and during the period of my studies. I was able to embark on and complete this project because of them. Whatever shortcomings in the study, though, remain mine. I appreciate my uncle and lecturer, Chief Pius Enebeli Opene, who put in my head the idea of joining the academia. Though he did not live to see me complete this program, I want him to know that his son completed the program successfully, and that his encouraging words still guide and motivate me as I strive for greater heights. Words fail me to adequately express my gratitude to my supervisor, PD Dr. Eric A. Anchimbe. His encouragements and confidence in me made me believe in myself again, for I was at the verge of giving up. -

Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger a Dissertation Submitted

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Rhythms of Value: Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Eric James Schmidt 2018 © Copyright by Eric James Schmidt 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Rhythms of Value: Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger by Eric James Schmidt Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Timothy D. Taylor, Chair This dissertation examines how Tuareg people in Niger use music to reckon with their increasing but incomplete entanglement in global neoliberal capitalism. I argue that a variety of social actors—Tuareg musicians, fans, festival organizers, and government officials, as well as music producers from Europe and North America—have come to regard Tuareg music as a resource by which to realize economic, political, and other social ambitions. Such treatment of culture-as-resource is intimately linked to the global expansion of neoliberal capitalism, which has led individual and collective subjects around the world to take on a more entrepreneurial nature by exploiting representations of their identities for a variety of ends. While Tuareg collective identity has strongly been tied to an economy of pastoralism and caravan trade, the contemporary moment demands a reimagining of what it means to be, and to survive as, Tuareg. Since the 1970s, cycles of drought, entrenched poverty, and periodic conflicts have pushed more and more Tuaregs to pursue wage labor in cities across northwestern Africa or to work as trans- ii Saharan smugglers; meanwhile, tourism expanded from the 1980s into one of the region’s biggest industries by drawing on pastoralist skills while capitalizing on strategic essentialisms of Tuareg culture and identity. -

Igbo Folktales and the Idea of Chukwu As Supreme God of Igbo Religion Chukwuma Azuonye, University of Massachusetts Boston

University of Massachusetts Boston From the SelectedWorks of Chukwuma Azuonye April, 1987 Igbo Folktales and the Idea of Chukwu as Supreme God of Igbo Religion Chukwuma Azuonye, University of Massachusetts Boston Available at: http://works.bepress.com/chukwuma_azuonye/76/ ISSN 0794·6961 NSUKKAJOURNAL OF LINGUISTICS AND AFRICAN LANGUAGES NUMBER 1, APRIL 1987 Published by the Department of Linguistics and Nigerian Languages, University of Nigeria, Nsukka NOTES ON THE CONTRIBUTORS All but one of the contributors to this maiden issue of The Nsukka Journal of Linguistics and African Languages are members of the Department of Linguistics and Nigerian Languages, Univerrsity of Nigeria, Nsukka Mr. B. N. Anasjudu is a Tutor in Applied Linguistics (specialized in Teaching English as a Second Language). Dr. Chukwuma Azyonye is a Senior Lecturer in Oral Literature and Stylistics and Acting Head of Department. Mrs. Clara Ikeke9nwy is a Lecturer in Phonetics and Phonology. Mr. Mataebere IwundV is a Senior Lecturer in Sociolinguistics and Psycholinguistics. Mrs. G. I. Nwaozuzu is a Graduate Assistant in Syntax and Semantics. She also teaches Igbo Literature. Dr. P. Akl,ljYQQbi Nwachukwu is a Senior Lecturer in Syntax and Semantics. Professor Benson Oluikpe is a Professor of Applied and Comparative Linguistics and Dean of the Faculty of Arts. Mr. Chibiko Okebalama is a Tutor in Literature and Stylistics. Dr. Sam VZ9chukwu is a Senior Lecturer in Oral Literature and Stylistics in the Department of African Languages and Literatures, University of Lagos. ISSN 0794-6961 Nsukka Journal of L,i.nguistics and African Languages Number 1, April 1987 IGBD FOLKTALES AND THE EVOLUTION OF THE IDEA OF CHUKWU AS THE SUPREME GOD OF IGBO RELIGION Chukwuma Azyonye This analysis of Igbo folktales reveals eight distinct phases in the evolution of the idea of Chukwu as the supreme God of Igbo religion. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

The Influence of the Supernatural in Elechi Amadi’S the Concubine and the Great Ponds

THE INFLUENCE OF THE SUPERNATURAL IN ELECHI AMADI’S THE CONCUBINE AND THE GREAT PONDS BY EKPENDU, CHIKODI IFEOMA PG/MA/09/51229 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND LITERARY STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA. SUPERVISOR: DR. EZUGU M.A A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF ARTS (M.A) IN ENGLISH & LITERARY STUDIES TO THE SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA. JANUARY, 2015 i TITLE PAGE THE INFLUENCE OF THE SUPERNATURAL IN ELECHI AMADI’S THE CONCUBINE AND THE GREAT PONDS BY EKPENDU, CHIKODI IFEOMA PG /MA/09/51229 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH & LITERARY STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA. JANUARY, 2015 ii CERTIFICATION This research work has been read and approved BY ________________________ ________________________ DR. M.A. EZUGU SIGNATURE & DATE SUPERVISOR ________________________ ________________________ PROF. D.U.OPATA SIGNATURE & DATE HEAD OF DEPARTMENT ________________________ ________________________ EXTERNAL EXAMINER SIGNATURE & DATE iii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my dear son Davids Smile for being with me all through the period of this study. To my beloved husband, Mr Smile Iwejua for his love, support and understanding. To my parents, Elder & Mrs S.C Ekpendu, for always being there for me. And finally to God, for his mercies. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My greatest thanks go to the Almighty God for his steadfast love and for bringing me thus far in my academics. To him be all the glory. My Supervisor, Dr Mike A. Ezugu who patiently taught, read and supervised this research work, your well of blessings will never run dry. My ever smiling husband, Mr Smile Iwejua, your smile and support took me a long way. -

South – East Zone

South – East Zone Abia State Contact Number/Enquires ‐08036725051 S/N City / Town Street Address 1 Aba Abia State Polytechnic, Aba 2 Aba Aba Main Park (Asa Road) 3 Aba Ogbor Hill (Opobo Junction) 4 Aba Iheoji Market (Ohanku, Aba) 5 Aba Osisioma By Express 6 Aba Eziama Aba North (Pz) 7 Aba 222 Clifford Road (Agm Church) 8 Aba Aba Town Hall, L.G Hqr, Aba South 9 Aba A.G.C. 39 Osusu Rd, Aba North 10 Aba A.G.C. 22 Ikonne Street, Aba North 11 Aba A.G.C. 252 Faulks Road, Aba North 12 Aba A.G.C. 84 Ohanku Road, Aba South 13 Aba A.G.C. Ukaegbu Ogbor Hill, Aba North 14 Aba A.G.C. Ozuitem, Aba South 15 Aba A.G.C. 55 Ogbonna Rd, Aba North 16 Aba Sda, 1 School Rd, Aba South 17 Aba Our Lady Of Rose Cath. Ngwa Rd, Aba South 18 Aba Abia State University Teaching Hospital – Hospital Road, Aba 19 Aba Ama Ogbonna/Osusu, Aba 20 Aba Ahia Ohuru, Aba 21 Aba Abayi Ariaria, Aba 22 Aba Seven ‐ Up Ogbor Hill, Aba 23 Aba Asa Nnetu – Spair Parts Market, Aba 24 Aba Zonal Board/Afor Une, Aba 25 Aba Obohia ‐ Our Lady Of Fatima, Aba 26 Aba Mr Bigs – Factory Road, Aba 27 Aba Ph Rd ‐ Udenwanyi, Aba 28 Aba Tony‐ Mas Becoz Fast Food‐ Umuode By Express, Aba 29 Aba Okpu Umuobo – By Aba Owerri Road, Aba 30 Aba Obikabia Junction – Ogbor Hill, Aba 31 Aba Ihemelandu – Evina, Aba 32 Aba East Street By Azikiwe – New Era Hospital, Aba 33 Aba Owerri – Aba Primary School, Aba 34 Aba Nigeria Breweries – Industrial Road, Aba 35 Aba Orie Ohabiam Market, Aba 36 Aba Jubilee By Asa Road, Aba 37 Aba St. -

Baby Factories": Exploitation of Women in Southern Nigeria Jacinta Chiamaka Nwaka University of Benin, Benin City, Nigeria, [email protected]

Dignity: A Journal on Sexual Exploitation and Violence Volume 4 | Issue 2 Article 2 March 2019 "Baby Factories": Exploitation of Women in Southern Nigeria Jacinta Chiamaka Nwaka University of Benin, Benin City, Nigeria, [email protected] Akachi Odoemene Federal University Otuoke, Nigeria, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/dignity Part of the African Studies Commons, Behavioral Economics Commons, Civic and Community Engagement Commons, Community-Based Research Commons, Criminology Commons, Domestic and Intimate Partner Violence Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Regional Economics Commons, Regional Sociology Commons, Rural Sociology Commons, Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons, Social History Commons, Social Psychology and Interaction Commons, and the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Nwaka, Jacinta Chiamaka and Odoemene, Akachi (2019) ""Baby Factories": Exploitation of Women in Southern Nigeria," Dignity: A Journal on Sexual Exploitation and Violence: Vol. 4: Iss. 2, Article 2. DOI: 10.23860/dignity.2019.04.02.02 Available at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/dignity/vol4/iss2/2https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/dignity/vol4/iss2/2 This Research and Scholarly Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dignity: A Journal on Sexual Exploitation and Violence by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Baby Factories": Exploitation of Women in Southern Nigeria Abstract Despite the writings of feminist thinkers and efforts of other advocates of feminism to change the dominant narratives on women, exploitation of women is a fact that has remained endemic in various parts of the world, and particularly in Africa. -

Mid-Term Evaluation of the Conflict Abatement Through Local Mitigation (Calm) Project Implemented by Ifesh Under Cooperative Agreement No

MID-TERM EVALUATION OF THE CONFLICT ABATEMENT THROUGH LOCAL MITIGATION (CALM) PROJECT IMPLEMENTED BY IFESH UNDER COOPERATIVE AGREEMENT NO. 620-A-00-05-000099-00 JUNE 2009 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by ARD, Inc. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The CALM Mid-term Evaluation team extends deep thanks to the some 200 project beneficiaries and partners of CALM in Delta, Kaduna, Kano, Plateau, and Rivers states who generously shared their time and thoughts during our interviews and discussions. We are also grateful to the IFESH/CALM staff for generously providing detailed information on their field activities and contacts, and for arranging a number of key interviews. IFESH headquarters in Phoenix kindly supplemented our documentation on the history and evolution of the project. We are grateful to a number of senior staff from government and donor organizations who expanded our understanding of present and future conflict mitigation and management initiatives in Nigeria. Special thanks goes to USAID Mission Director Sharon Cromer in Abuja for her warm welcome and interest in the evaluation; to the Peace, Democracy and Governance Team for their hands-on support; to staff and team leaders who shared their insights; and to MEMS for review of the project monitoring and evaluation plan. Finally, we gratefully acknowledge the constant and conscientious support of our field research associates: Ali Garba, Institute of Governance and Social Research (IGSR), Jos; Rosemary Osikoya, Jos; Dr. Christy George, Kate Bee Foundation, Port Harcourt; and Kingsley Akeni, AFSTRAG Consults Limited, Warri. This report has been prepared for the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), under Contract No. -

Community's Influence on Igbo Musical Artiste and His

International Journal of Literature and Arts 2019; 7(1): 1-8 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ijla doi: 10.11648/j.ijla.20190701.11 ISSN: 2331-0553 (Print); ISSN: 2331-057X (Online) Community’s Influence on Igbo Musical Artiste and His Art Alvan-Ikoku Okwudiri Nwamara Department of Music, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria Email address: To cite this article: Alvan-Ikoku Okwudiri Nwamara. Community’s Influence on Igbo Musical Artiste and His Art. International Journal of Literature and Arts . Vol. 7, No. 1, 2019, pp. 1-8. doi: 10.11648/j.ijla.20190701.11 Received : September 19, 2018; Accepted : October 17, 2018; Published : March 11, 2019 Abstract: The Igbo traditional concept of “Ohaka: The Community is Supreme,” is mostly expressed in Igbo names like; Nwoha/Nwora (Community-Owned Child), Oranekwulu/Ohanekwulu (Community Intercedes/intervenes), Obiora/Obioha (Community-Owned Son), Adaora/Adaoha (Community-Owned Daughter) etc. This indicates value attached to Ora/Oha (Community) in Igbo culture. Musical studies have shown that the Igbo musical artiste does not exist in isolation; rather, he performs in/for his community and is guided by the norms and values of his culture. Most Igbo musicological scholars affirm that some of his works require the community as co-performers while some require collaboration with some gifted members of his community. His musical instruments are approved and often times constructed by members of his community as well as his costumes and other paraphernalia. But in recent times, modernity has not been so friendly to this “Ohaka” concept; hence the promotion of individuality/individualism concepts in various guises within the context of Igbo musical arts performance. -

“YORUBA's DON't DO GENDER”: a CRITICAL REVIEW of OYERONKE OYEWUMI's the Invention of Women

“YORUBA’S DON’T DO GENDER”: A CRITICAL REVIEW OF OYERONKE OYEWUMI’s The Invention of Women: Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses By Bibi Bakare-Yusuf Discourses on Africa, especially those refracted through the prism of developmentalism, promote gender analysis as indispensable to the economic and political development of the African future. Conferences, books, policies, capital, energy and careers have been made in its name. Despite this, there has been very little interrogation of the concept in terms of its relevance and applicability to the African situation. Instead, gender functions as a given: it is taken to be a cross-cultural organising principle. Recently, some African scholars have begun to question the explanatory power of gender in African societies.1 This challenge came out of the desire to produce concepts grounded in African thought and everyday lived realities. These scholars hope that by focusing on an African episteme they will avoid any dependency on European theoretical paradigms and therefore eschew what Babalola Olabiyi Yai (1999) has called “dubious universals” and “intransitive discourses”. Some of the key questions that have been raised include: can gender, or indeed patriarchy, be applied to non- Euro-American cultures? Can we assume that social relations in all societies are organised around biological sex difference? Is the male body in African societies seen as normative and therefore a conduit for the exercise of power? Is the female body inherently subordinate to the male body? What are -

A Study of the Ewe Unification Movement in the United States

HOME AWAY FROM HOME: A STUDY OF THE EWE UNIFICATION MOVEMENT IN THE UNITED STATES BY DJIFA KOTHOR THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in African Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Master’s Committee: Professor Faranak Miraftab, Chair Professor Kathryn Oberdeck Professor Alfred Kagan ABSTRACT This master’s thesis attempts to identity the reasons and causes for strong Ewe identity among those in the contemporary African Diaspora in the United States. An important debate among African nationalists and academics argues that ethnic belonging is a response to colonialism instigated by Western-educated African elites for their own political gain. Based on my observation of Ewe political discourses of discontent with the Ghana and Togolese governments, and through my exploratory interviews with Ewe immigrants in the United States; I argue that the formation of ethnic belonging and consciousness cannot be reduced to its explanation as a colonial project. Ewe politics whether in the diaspora, Ghana or Togo is due to two factors: the Ewe ethnonational consciousness in the period before independence; and the political marginalization of Ewes in the post-independence period of Ghana and Togo. Moreover, within the United States discrimination and racial prejudice against African Americans contribute to Ewe ethnic consciousness beyond their Togo or Ghana formal national belongings towards the formation of the Ewe associations in the United States. To understand the strong sense of Ewe identity among those living in the United States, I focus on the historical questions of ethnicity, regionalism and politics in Ghana and Togo.