Win-Win Or Lose

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Art List by Year

ART LIST BY YEAR Page Period Year Title Medium Artist Location 36 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Standard of Ur Inlaid Box British Museum 36 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Stele of the Vultures (Victory Stele of Eannatum) Limestone Louvre 38 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Bull Headed Harp Harp British Museum 39 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Banquet Scene cylinder seal Lapis Lazoli British Museum 40 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2254 Victory Stele of Narum-Sin Sandstone Louvre 42 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2100 Gudea Seated Diorite Louvre 43 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2100 Gudea Standing Calcite Louvre 44 Mesopotamia Babylonian 1780 Stele of Hammurabi Basalt Louvre 45 Mesopotamia Assyrian 1350 Statue of Queen Napir-Asu Bronze Louvre 46 Mesopotamia Assyrian 750 Lamassu (man headed winged bull 13') Limestone Louvre 48 Mesopotamia Assyrian 640 Ashurbanipal hunting lions Relief Gypsum British Museum 65 Egypt Old Kingdom 2500 Seated Scribe Limestone Louvre 75 Egypt New Kingdom 1400 Nebamun hunting fowl Fresco British Museum 75 Egypt New Kingdom 1400 Nebamun funery banquet Fresco British Museum 80 Egypt New Kingdom 1300 Last Judgement of Hunefer Papyrus Scroll British Museum 81 Egypt First Millenium 680 Taharqo as a sphinx (2') Granite British Museum 110 Ancient Greece Orientalizing 625 Corinthian Black Figure Amphora Vase British Museum 111 Ancient Greece Orientalizing 625 Lady of Auxerre (Kore from Crete) Limestone Louvre 121 Ancient Greece Archaic 540 Achilles & Ajax Vase Execias Vatican 122 Ancient Greece Archaic 510 Herakles wrestling Antaios Vase Louvre 133 Ancient Greece High -

After the Battle Is Over: the Stele of the Vultures and the Beginning Of

To raise the ofthe natureof narrative is to invite After the Battle Is Over: The Stele question reflectionon the verynature of culture. Hayden White, "The Value of Narrativity . ," 1981 of the Vultures and the Beginning of Historical Narrative in the Art Definitions of narrative, generallyfalling within the purviewof literarycriticism, are nonethelessimportant to of the Ancient Near East arthistorians. From the simpleststarting point, "for writing to be narrative,no moreand no less thana tellerand a tale are required.'1 Narrativeis, in otherwords, a solutionto " 2 the problemof "how to translateknowing into telling. In general,narrative may be said to make use ofthird-person cases and of past tenses, such that the teller of the story standssomehow outside and separatefrom the action.3But IRENE J. WINTER what is importantis thatnarrative cannot be equated with thestory alone; it is content(story) structured by the telling, University of Pennsylvania forthe organization of the story is whatturns it into narrative.4 Such a definitionwould seem to providefertile ground forart-historical inquiry; for what, after all, is a paintingor relief,if not contentordered by the telling(composition)? Yet, not all figuraiworks "tell" a story.Sometimes they "refer"to a story;and sometimesthey embody an abstract concept withoutthe necessaryaction and settingof a tale at all. For an investigationof visual representation, it seems importantto distinguishbetween instancesin which the narrativeis vested in a verbal text- the images servingas but illustrationsof the text,not necessarily"narrative" in themselves,but ratherreferences to the narrative- and instancesin whichthe narrativeis located in the represen- tations,the storyreadable throughthe images. In the specificcase of the ancientNear East, instances in whichnarrative is carriedthrough the imageryitself are rare,reflecting a situationfundamentally different from that foundsubsequently in the West, and oftenfrom that found in the furtherEast as well. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

DESENVOLVIMENTO DO ESQUEMA DECORATIVO DAS SALAS DO TRONO DO PERÍODO NEO-ASSÍRIO (934-609 A.C.): IMAGEM TEXTO E ESPAÇO COMO VE

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO MUSEU DE ARQUEOLOGIA E ETNOLOGIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ARQUEOLOGIA DESENVOLVIMENTO DO ESQUEMA DECORATIVO DAS SALAS DO TRONO DO PERÍODO NEO-ASSÍRIO (934-609 a.C.): IMAGEM TEXTO E ESPAÇO COMO VEÍCULOS DA RETÓRICA REAL VOLUME I PHILIPPE RACY TAKLA Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Arqueologia do Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia da Universidade de São Paulo para obtenção do título de Mestre em Arqueologia. Orientadora: Profª. Drª. ELAINE FARIAS VELOSO HIRATA Linha de Pesquisa: REPRESENTAÇÕES SIMBÓLICAS EM ARQUEOLOGIA São Paulo 2008 RESUMO Este trabalho busca a elaboração de um quadro interpretativo que possibilite analisar o desenvolvimento do esquema decorativo presente nas salas do trono dos palácios construídos pelos reis assírios durante o período que veio a ser conhecido como neo- assírio (934 – 609 a.C.). Entendemos como esquema decorativo a presença de imagens e textos inseridos em um contexto arquitetural. Temos por objetivo demonstrar que a evolução do esquema decorativo, dada sua importância como veículo da retórica real, reflete a transformação da política e da ideologia imperial, bem como das fronteiras do império, ao longo do período neo-assírio. Palavras-chave: Assíria, Palácio, Iconografia, Arqueologia, Ideologia. 2 ABSTRACT The aim of this work is the elaboration of a interpretative framework that allow us to analyze the development of the decorative scheme of the throne rooms located at the palaces built by the Assyrians kings during the period that become known as Neo- Assyrian (934 – 609 BC). We consider decorative scheme as being the presence of texts and images in an architectural setting. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49596-7 — the Amorites and the Bronze Age Near East Aaron A

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49596-7 — The Amorites and the Bronze Age Near East Aaron A. Burke Index More Information INDEX ꜤꜢmw (Egyptian term), 145–47 See also Asiatics “communities of practice,” 18–20, 38–40, 42, (Egypt) 347–48 decline of, 350–51 A’ali, 226 during Early Bronze Age, 31 ‘Aa-zeh-Re’ Nehesy, 316–17 Ebla, 38–40, 56, 178 Abarsal, 45 emergence of, 23, 346–47 Abda-El (Amorite), 153–54 extensification of, 18–20 Abi-eshuh, 297, 334–35 hollow cities, 178–79 Abisare (Larsa), 160 Jazira, 38, 177 Abishemu I (Byblos), 175 “land rush,” 177–78 Abraham, 6 Mari, 38–40, 56, 177–79, 227–28 abu as symbolic kinship, 268–70 Nawar, 38, 40, 42 Abu en-Ni’aj, Tell, 65 Northern Levant, 177 Abu Hamad, 54 Qatna, 179 Abu Salabikh, 100 revival of, 176–80, 357 Abusch, Tzvi, 186 Shubat Enlil, 177–78, 180 Abydos, 220 social identity of Amorites and, 10 Achaemenid Empire, 12 Urkesh, 38, 42 Achsaph, 176 wool trade and, 23 ‘Adabal (deity), 40 Yamḫ ad, 179 Adad/Hadad (deity), 58–59, 134, 209–10, 228–29, zone of uncertainty and, 24, 174 264, 309–11, 338, 364 Ahbabu, 131 Adams, Robert, 128 Ahbutum (tribe), 97 Adamsah, 109 Ahktoy III, 147 Adba-El (Mari), 153–54 Ahmar, Tell, 51–53, 56, 136, 228 Addahushu (Elam), 320 Ahmose, 341–42 Ader, 50 ‘Ai, 33 Admonitions of Ipuwer, 172 ‘Ain Zurekiyeh, 237–38 aDNA. See DNA Ajjul, Tell el-, 142, 237–38, 326, 329, 341–42 Adnigkudu (deity), 254–55 Akkadian Empire. -

The Lagash-Umma Border Conflict 9

CHAPTER I Introduction: Early Civilization and Political Organization in Babylonia' The earliest large urban agglomoration in Mesopotamia was the city known as Uruk in later texts. There, around 3000 B.C., certain distinctive features of historic Mesopotamian civilization emerged: the cylinder seal, a system of writing that soon became cuneiform, a repertoire of religious symbolism, and various artistic and architectural motifs and conven- tions.' Another feature of Mesopotamian civilization in the early historic periods, the con- stellation of more or less independent city-states resistant to the establishment of a strong central political force, was probably characteristic of this proto-historic period as well. Uruk, by virtue of its size, must have played a dominant role in southern Babylonia, and the city of Kish probably played a similar role in the north. From the period that archaeologists call Early Dynastic I1 (ED 11), beginning about 2700 B.c.,~the appearance of walls around Babylonian cities suggests that inter-city warfare had become institutionalized. The earliest royal inscriptions, which date to this period, belong to kings of Kish, a northern Babylonian city, but were found in the Diyala region, at Nippur, at Adab and at Girsu. Those at Adab and Girsu are from the later part of ED I1 and are in the name of Mesalim, king of Kish, accompanied by the names of the respective local ruler^.^ The king of Kish thus exercised hegemony far beyond the walls of his own city, and the memory of this particular king survived in native historical traditions for centuries: the Lagash-Umma border was represented in the inscriptions from Lagash as having been determined by the god Enlil, but actually drawn by Mesalim, king of Kish (IV.1). -

Chapter 2 the Rise of Civilization: the Art of the Ancient Near East

Chapter 2 The Rise of Civilization: The Art of the Ancient Near East Multiple Choice Select the response that best answers the question or completes the statement. 1. The change in the nature of daily life, from hunter and gatherer to farmer and herder, first occurred in ______________. a. Mesopotamia c. Africa b. Europe d. Asia 2. Mesopotamia is known as the __________ ___________. a. River Crescent c. Fertile Crescent b. Delta Crescent d. Pearl Crescent 3. The ___________ ruled the northern Mesopotamian empire during the ninth through seventh centuries BCE. a. Sumerians c. Akkadians b. Assyrians d. Sasanians 4. What site did Leonard Woolley excavate in the 1920s in southern Mesopotamia? a. Royal Cemetery at Giza c. Royal Palace at Nineveh b. Ziggurat of Ur d. Royal Cemetery at Ur 5. The ___________ are credited with developing the first known writing system. a. Assyrians c. Sumerians b. Babylonians d. Elamites 6. The most famous Sumerian work of literature is the _____________________. a. Illiad c. Odyssey b. Tale of Gilgamesh d. Tale of Urnanshe 7. In Sumerian cities the ________ formed the nucleus of the city. a. temple c. palace b. market d. treasury 8. The temples of Sumer were placed on high platforms or ___________. a. pyramids c. daises b. ziggurats d. towers 9. What is the theme of the Stele of the Vultures? a. warfare c. trade b. prayer d. royal contract 7 10. The earliest known name of an author is _____________. a. Nanna c. Sargon b. Enheduanna d. Gudea 11. Hammurabi is most famous for his ____________. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 11/01/2019 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 11/01/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry The Old Lamplighter Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Someday You'll Want Me To Want You (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Blackout Heartaches That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Other Side Cheek to Cheek I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET 10 Years My Romance Aren't You Glad You're You Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together No Love No Nothin' Because The Night Kumbaya Personality 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris Sunday, Monday Or Always Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are This Heart Of Mine I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mister Meadowlark The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine 1950s Standards Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Get Me To The Church On Time Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) Fly Me To The Moon 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Cupid Body And Soul Crawdad Song Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze Christmas In Killarney 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven That's Amore Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Organ Grinder's Swing Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Lullaby Of Birdland Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Rags To Riches 1800s Standards I Thought About You Something's Gotta Give Home Sweet Home -

An AZ Companion to Ancient Egyptian Architecture Free

FREE THE MONUMENTS OF EGYPT: AN A-Z COMPANION TO ANCIENT EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE PDF Dieter Arnold | 288 pages | 30 Nov 2009 | I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd | 9781848850422 | English | London, United Kingdom Art of ancient Egypt - Wikipedia Egyptian inventions and discoveries are objects, processes or techniques which owe their existence either partially or entirely to an Egyptian person. Often, things which are discovered for the first time, are also called "inventions", and in many cases, there is no clear line between the two. Below is a list of such inventions. Furniture became common first in Ancient Egypt during the Naqada culture. During that period a wide variety of furniture pieces were invented and used. Atalla and Dawon Kahng at Bell Labs in[] enabled the practical use of metal—oxide—semiconductor MOS transistors as memory cell storage elements, a function previously served by magnetic cores. MOSFET scaling and miniaturization see List of semiconductor scale examples have been the primary factors behind the rapid exponential growth of electronic semiconductor technology since the s, [] as the rapid miniaturization of MOSFETs has been largely responsible for the increasing The Monuments of Egypt: An A-Z Companion to Ancient Egyptian Architecture densityincreasing performance and decreasing power consumption of integrated circuit chips and electronic devices since the s. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Redirected from List of egyptian inventions and discoveries. This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. June Archived from the original on Archived from the original PDF on January A history of ancient Egypt. Shaw, Ian, —. Oxford, UK: — Mark 4 November Ancient History Encyclopedia. -

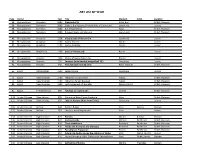

O 0 0 El 23 0

R&B SONGSTM R&B ALéuMSTM Fantasia's 2 WK5 LAST THIS PEAK WAS ON LAST THIS ARTIST Title YKS. ON TITLE Artist CERT. POS. WEEK WE/K (HART AGO WEEK WEEK PRODUCER (SONGWRITER) IMPRINT/PROMOTION LABEL CVART IMPRINT/DISTRIBUTING LABEL No.1 SUIT & TIE Justin Timberlake Featuring Jay Z A 1 16 FANTASIA Side Effects Of You t EONES Om- n I +V 19/RU TIM NAIWIEBF0A4 E ALUUWIIURD LIST W EA NEW Or 'Effects' 2 5 JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE The 20/20 Experience 6 17 BODY PARTY Ciara 1 2 RCA m0 ROL WKLMACKII.PNA51Y)C.NARMLII WIEIPSCASHJIAMERONEL NR(M4SKPALARMITERS ~DM R3 »RN EPIC "American Idol" season -three Unapologetic 16 5 NEXT TO ME Emeli Sande 3 12 2 3 RIHANNA Champion Fantasia (below) SRP/DER LAM/IDIMG © 0 CRAIE.HOAK IA.E.SANDE,11,(HEGWINH.CRAZI A.PAULI CAPITOL continues to win on Top R&B/ POUR IT UP Rihanna 2 23 a MIGUEL Kaleidoscope Dream 16 Hip -Hop Albums as her fourth ICE/RCA MIKE WILL LOAD) ITT E:DIM.I.WILLIAMSII-LGARNER.T.INOMAS,I.THOMAS.R.FENTYI SRP/DEF IAM/IDIMG BYSTORM/BLACK release. Side Effects of vou, FINE CHINA Chris Brown 4 4 EMELI SANDE Our Version Of Events 16 with CAPITOL opens atop the chart ' M BROWN,A.STREETER,L.YOUNGBLOOD.G.DEGEDOINGSEZL.E.BELLINGI RI RCA 91,000 copies, according ADORN Miguel 2 30 NEW EMELI SANDE iTunes Session (EP) 1 O 1 to Nielsen SoundScan. All M IPIMENTEL) BISTORM/BLACK ICE/RCA (A three of her previous albums 1 On Fire 16 7 7 DIAMONDS Rihanna © 30 4 CO ALICIA KEYS Girl 8 RC ATE.BENNY BLANCO (S.EURLER.B.LEVIN.M.S.ERIKSEM,T.E.HERMANSEN) SRP/)EP IAM/I111MG ' debuted in the top five with her last set, Back to Me (2010). -

Povestiri Din Orient (Tâlcuite În Versuri Pentru Cei Mici) Volumul I: Mul-An, Muzica Stelelor Cerului Şi Monologul Scepticului

DOBRE I. VALENTIN-CLAUDIU – POVESTIRI DIN ORIENT (TÂLCUITE ÎN VERSURI PENTRU CEI MICI) VOLUMUL I: MUL-AN, MUZICA STELELOR CERULUI ŞI MONOLOGUL SCEPTICULUI Valentin-Claudiu I. DOBRE POVESTIRI DIN ORIENT (TÂLCUITE ÎN VERSURI PENTRU CEI MICI) VOLUMUL I: MUL-AN, MUZICA STELELOR CERULUI ŞI MONOLOGUL SCEPTICULUI 0 - 962 1 3 - 0 COLECŢIA ZIDUL DE HÂRTIE - 973 Ediţie electronică pdf CD-ROM 2020 - BUCUREŞTI 2020 ISBN ISBN 978 ISBN 978-973-0-31962-0 1 Page DOBRE I. VALENTIN-CLAUDIU – POVESTIRI DIN ORIENT (TÂLCUITE ÎN VERSURI PENTRU CEI MICI) VOLUMUL I: MUL-AN, MUZICA STELELOR CERULUI ŞI MONOLOGUL SCEPTICULUI Valentin-Claudiu I. DOBRE POVESTIRI DIN ORIENT (TÂLCUITE ÎN VERSURI PENTRU CEI MICI). VOLUMUL I: MUL-AN, MUZICA STELELOR CERULUI ŞI MONOLOGUL SCEPTICULUI Ediţie electronică pdf CD-ROM 2020 0 Dedicată Celor Dragi, Soţiei mele iubite - 962 1 3 - COLECŢIA ZIDUL DE HÂRTIE 0 - 973 - Ediţie electronică pdf CD-ROM 2020 Bucureşti 2020 ISBN 978 ISBN 978-973-0-31962-0 2 Page DOBRE I. VALENTIN-CLAUDIU – POVESTIRI DIN ORIENT (TÂLCUITE ÎN VERSURI PENTRU CEI MICI) VOLUMUL I: MUL-AN, MUZICA STELELOR CERULUI ŞI MONOLOGUL SCEPTICULUI Drepturile asupra acestei ediţii aparţin autorului. Orice reproducere fără indicarea sursei strict prohibită. Lucrările grafice redate nu au restricții de reproducere. SURSELE TEXTELOR ORIGINALE: - ETCSL Project, Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Oxford; Adresă site: http: //etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/edition2/etcslbynumb.php - Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (CDLB- Bulletin şi CDLJ- Journal); Adresă site: http: //cdli.ucla.edu - ETCSRI Corpus; Adresă site: http: //oracc.museum.upenn.edu/etcsri/corpus - Colecţia Montserrat Museum, Barcelona, Spain, studii Molina Manuel; Adresă site: http: //bdtns.filol.csic.es - Cuneiform Monographs Vol.