Keeping It Real: a Historical Look at Reality TV

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Power Seeking and Backlash Against Female Politicians

Article Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin The Price of Power: Power Seeking and 36(7) 923 –936 © 2010 by the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc Backlash Against Female Politicians Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0146167210371949 http://pspb.sagepub.com Tyler G. Okimoto1 and Victoria L. Brescoll1 Abstract Two experimental studies examined the effect of power-seeking intentions on backlash toward women in political office. It was hypothesized that a female politician’s career progress may be hindered by the belief that she seeks power, as this desire may violate prescribed communal expectations for women and thereby elicit interpersonal penalties. Results suggested that voting preferences for female candidates were negatively influenced by her power-seeking intentions (actual or perceived) but that preferences for male candidates were unaffected by power-seeking intentions. These differential reactions were partly explained by the perceived lack of communality implied by women’s power-seeking intentions, resulting in lower perceived competence and feelings of moral outrage. The presence of moral-emotional reactions suggests that backlash arises from the violation of communal prescriptions rather than normative deviations more generally. These findings illuminate one potential source of gender bias in politics. Keywords gender stereotypes, backlash, power, politics, intention, moral outrage Received June 5, 2009; revision accepted December 2, 2009 Many voters see Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton as coldly politicians and that these penalties may be reflected in voting ambitious, a perception that could ultimately doom her presi- preferences. dential campaign. Peter Nicholas, Los Angeles Times, 2007 Power-Relevant Stereotypes Power seeking may be incongruent with traditional female In 1916, Jeannette Rankin was elected to the Montana seat in gender stereotypes but not male gender stereotypes for a the U.S. -

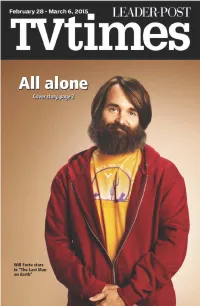

One and Only

Cover Story One and only Fox tackles the loneliest number in ‘The Last Man on Earth’ By Cassie Dresch people after a virus takes out him get into a lot of really silly TV Media all of Earth’s population. His shenanigans. family is gone, his coworkers “It’s all just kind of stupid ello? Hi? Anybody out are gone, the president is gone. stuff that I go around and do,” Hthere? Of course there is, Everyone. Gone. he said in an interview with otherwise life would be very, So what does he do? He “Entertainment Weekly.” very, very lonely. Fox is taking a travels the United States doing “That’s been one of the most stab at the ultimate life of lone- things he never would have fun parts of the job. About once liness in the new half-hour been able to do otherwise — a week I get to do something comedy “The Last Man on sing the national anthem at that seems like it’d be amaz- Earth,” premiering Sunday, Dodger Stadium, smear gooey ingly fun to do: shoot a flame March 1. peanut butter all over a price- thrower at a bunch of wigs, The premise around “Last less piece of art ... then walk have a steamroller steamroll Man” is a simple one, albeit a away with it, break things. The over a case of beer. Just dumb little strange. An average, un- show, according to creator and stuff like that, which pretty assuming man is on the hunt star Will Forte (“Saturday Night much is all it takes to make me for any signs of other living Live,” “Nebraska,” 2013), sees happy.” Registration $25.00 online: www.skseniorsmechanism.ca or phone 306-359-9956 2 Cover Story Flame throwers and steam- ally proud of what has come rollers? Again, it’s a strange out of it so far.” concept, but Fox is really be- Of course, you have to won- Index hind the show. -

Nationalism and the Collapse of Soviet Communism

Nationalism and the Collapse of Soviet Communism MARK R. BEISSINGER Abstract This article examines the role of nationalism in the collapse of communism in the late 1980s and early 1990s, arguing that nationalism (both in its presence and its absence, and in the various conflicts and disorders that it unleashed) played an important role in structuring the way in which communism collapsed. Two institutions of international and cultural control in particular – the Warsaw Pact and ethnofederalism – played key roles in determining which communist regimes failed and which survived. The article argues that the collapse of communism was not a series of isolated, individual national stories of resistance but a set of interrelated streams of activity in which action in one context profoundly affected action in other contexts – part of a larger tide of assertions of national sovereignty that swept through the Soviet empire during this period. That nationalism should be considered among the causes of the collapse of communism is not a view shared by everyone. A number of works on the end of communism in the Soviet Union have argued, for instance, that nationalism played only a minor role in the process – that the main events took place within official institutions in Moscow and had relatively little to do with society, or that nationalism was a marginal motivation or influence on the actions of those involved in key decision-making. Failed institutions and ideologies, an economy in decline, the burden of military competition with the United States and instrumental goals of self-enrichment among the nomenklatura instead loom large in these accounts.1 In many narratives of the end of communism, nationalism is portrayed merely as a consequence of communism’s demise, as a phase after communism disintegrated – not as an autonomous or contributing force within the process of collapse itself. -

American Idol Synthesis

English Language and Composition Reading Time: 15 minutes Suggested Writing Time: 40 minutes Directions: The following prompt is based on the accompanying four sources. This question requires you to integrate a variety of sources into a coherent, well-written essay. Refer to the sources to support your position: avoid mere paraphrase or summary. Your argument should be central; the sources should support this argument. Remember to attribute both direct and indirect citations. Introduction In a culture of television in which the sensations of one season must be “topped” in the next, where do we draw the line between decency and entertainment? In the sixth season of popular TV show, “American Idol”, many Americans felt that the inclusion of mentally disabled contestants was inappropriate and that the remarks made to these contestants were both cruel and distasteful. Did this television show allow mentally disabled contestants in order to exploit them for entertainment? Assignment Read the following sources (including any introductory information) carefully. Then, in an essay that synthesizes the sources for support, take a position that defends, challenges, or qualifies the claim that the treatment of mentally disabled reality TV show contestant, Jonathan Jayne, was exploitative. Refer to the sources as Source A, Source B, etc.: titles are included for your convenience. Source A (Americans with Disabilities Act) Source B (Kelleher) Source C (Goldstein) Source D (Special Olympics) **Question composed and sources compiled by AP English Language and Composition teacher Wendy Turner, Paul Laurence Dunbar High School, Lexington, KY, on February 7, 2007. Source A The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. -

COOKBOOK for a CAUSE Volume 2

COOKBOOK FOR A CAUSE volume 2 TLC’S STARS SHARE FAVORITE RECIPES TO BENEFIT FEEDING AMERICA® FIGHTING HUNGER IN AMERICA ONE COOKBOOK at A TIME. The Pampered Chef® Cookbook for a Cause, Volume 2 benefits Feeding America®, the nation’s largest domestic hunger-relief organization. This year, the popular television network TLC® joined our mission to help fight hunger. TLC® stars from Cake Boss, Say Yes to the Dress, DC Cupcakes, The Little Couple, 19 Kids and Counting, What Not To Wear, and more, generously contributed their favorite recipes, in their own words. For each cookbook sold, we’ll donate $1 to Feeding America® to help provide eight meals to those in need.* We hope you’ll enjoy these recipes from the TLC® stars and the helpful tips and techniques from the experts in The Pampered Chef® Test Kitchens. As you gather around the table with family and friends, you can feel good that you’re helping another family in need to do the same. The Pampered Chef® The Pampered Chef® is the largest direct seller of everything you need to cook and entertain at home. At in-home Cooking Shows, guests see and try products, prepare and sample recipes, and learn quick and easy food preparation techniques and tips on how to entertain with style and ease — transforming the everyday into the extraordinary. TLC® is all about real-life reality, transporting the viewers into the lives of real-life extraordinary people with character. TLC® programs are entertaining, unfiltered and always reveal something worthwhile. TLC® is curious about people and finding the extraordinary in the everyday. -

Frontlash/Backlash: the Crisis of Solidarity and the Threat to Civil Institutions

Ó American Sociological Association 2018 DOI: 10.1177/0094306118815497 http://cs.sagepub.com FEATURED ESSAY Frontlash/Backlash: The Crisis of Solidarity and the Threat to Civil Institutions JEFFREY C. ALEXANDER Yale University [email protected] It is fear and loathing time for the left, sociol- The first thing to recognize is that ogists prominently among them. Loathing Trumpism and the alt-right are nothing for President Trump, champion of the alt- new, not here, not anywhere where right forces that, marginalized for decades, civil spheres have been simultaneously are bringing bigotry, patriarchy, nativism, and enabled and constrained. The depredations nationalism back into a visible place in the of Trumpism are not unique, first-time-in- American civil sphere. Fear that these threaten- American-history things. What they con- ing forces may succeed, that democracy will be stitute, instead, are backlash movements destroyed, and that the egalitarian achieve- (Alexander 2013). ments of the last five decades will be lost. Fem- Sociologists have had a bad habit of think- inism, anti-racism, multiculturalism, sexual cit- ing of social change as linear, a secular trend izenship, ecology, and internationalism—all that is broadly progressive, rooted in the these precarious achievements have come enlightening habits of modernity, education, under vicious, persistent attack. economic expansion, and the shared social Fear and loathing can be productive when interests of humankind (Marshall 1965; they are unleashed inside the culture and Parsons 1967; Habermas [1984, 1987] 1981; social structures of a civil sphere that remains Giddens 1990). From such a perspective, con- vigorous and a vital center (Schlesinger 1949; servative movements appear as deviations, Alexander 2016; Kivisto 2019) that, even if reflecting anomie and isolation (Putnam fragile, continues to hold. -

06 4-15-14 TV Guide.Indd

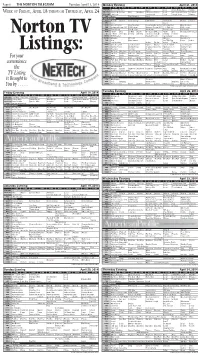

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2014 Monday Evening April 21, 2014 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline WEEK OF FRIDAY, APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY, APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS 2 Broke G Friends Mike Big Bang NCIS: Los Angeles Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson KSNK/NBC The Voice The Blacklist Local Tonight Show Meyers FOX Bones The Following Local Cable Channels A&E Duck D. Duck D. Duck Dynasty Bates Motel Bates Motel Duck D. Duck D. AMC Jaws Jaws 2 ANIM River Monsters River Monsters Rocky Bounty Hunters River Monsters River Monsters CNN Anderson Cooper 360 CNN Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront CNN Tonight DISC Fast N' Loud Fast N' Loud Car Hoards Fast N' Loud Car Hoards DISN I Didn't Dog Liv-Mad. Austin Good Luck Win, Lose Austin Dog Good Luck Good Luck E! E! News The Fabul Chrisley Chrisley Secret Societies Of Chelsea E! News Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Olbermann ESPN2 NFL Live 30 for 30 NFL Live SportsCenter FAM Hop Who Framed The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Step Brothers Archer Archer Archer Tomcats HGTV Love It or List It Love It or List It Hunters Hunters Love It or List It Love It or List It HIST Swamp People Swamp People Down East Dickering America's Book Swamp People LIFE Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Listings: MTV Girl Code Girl Code 16 and Pregnant 16 and Pregnant House of Food 16 and Pregnant NICK Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Friends Friends Friends SCI Metal Metal Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Metal Metal For your SPIKE Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Jail Jail TBS Fam. -

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

Reality Television Participants As Limited-Purpose Public Figures

Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law Volume 6 Issue 1 Issue 1 - Fall 2003 Article 4 2003 Almost Famous: Reality Television Participants as Limited- Purpose Public Figures Darby Green Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw Part of the Privacy Law Commons Recommended Citation Darby Green, Almost Famous: Reality Television Participants as Limited-Purpose Public Figures, 6 Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law 94 (2020) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw/vol6/iss1/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. All is ephemeral - fame and the famous as well. betrothal of complete strangers.' The Surreal Life, Celebrity - Marcus Aurelius (A.D 12 1-180), Meditations IV Mole, and I'm a Celebrity: Get Me Out of Here! feature B-list celebrities in reality television situations. Are You Hot places In the future everyone will be world-famous for fifteen half-naked twenty-somethings in the limelight, where their minutes. egos are validated or vilified by celebrity judges.' Temptation -Andy Warhol (A.D. 1928-1987) Island and Paradise Hotel place half-naked twenty-somethings in a tropical setting, where their amorous affairs are tracked.' TheAnna Nicole Show, the now-defunct The Real Roseanne In the highly lauded 2003 Golden Globe® and Show, and The Osbournes showcase the daily lives of Academy Award® winner for best motion-picture, Chicago foulmouthed celebrities and their families and friends. -

September 11 Backlash Employment Discrimination

September 11 Backlash Employment Discrimination by Bryan P. Cavanaugh1 Complaints of national origin-related employment discrimination have risen since September 11, 2001. The federal government is particularly concerned and has fostered an environment that employers should heed. It has sued employers around the country for September 11 backlash discrimination. Employers should forbid national origin discrimination, guard against it, and eradicate it as soon as they discover it. Otherwise, they could face expensive lawsuits. I. Introduction The events and images of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks affected everyone in the United States. The ghastly images of the attacks on our country by Muslim extremists are indelible in this country's collective memory. As President Bush addressed the nation on the night of September 11, 2001, he vowed, "None of us will ever forget this day."2 While September 11's precise effect upon the U.S. economy is unclear, it cannot be reasonably disputed that the attacks harmed it. Indeed, this country continues to feel the effects of the September 11 attacks. Naturally, the effects have reached the U.S. workplace. The attacks have affected the U.S. workforce as a whole and on a more personal level. Anecdotes abound of post-September 11 animosity and downright hatred of Arab-Americans and Muslims. This tension has increased allegations of unlawful employment discrimination throughout the U.S., including in Missouri. Since almost immediately after September 11, 2001, the federal government has expressed its heightened concern and special commitment to shed light on and to eradicate employment discrimination based on national origin. -

Idol Season 9: Top 4 -- Crystal Back in Action

BIG NEWS: Celebrity Skin | Jersey Shore | Ellen Degeneres | Celebrity Body | Energy Debates | More... LOG IN | SIGN UP JANUARY 7, 2011 FRONT PAGE POLITICS BUSINESS MEDIA ENTERTAINMENT COMEDY SPORTS STYLE WORLD GREEN FOOD TRAVEL TECH LIVING HEALTH DIVORCE ARTS BOOKS RELIGION IMPACT EDUCATION COLLEGE NY LA CHICAGO DENVER BLOGS Michael Giltz BIO Get Email Alerts Freelance writer and raconteur Become a Fan Bloggers' Index MOST POPULAR ON HUFFPOST Posted: May 12, 2010 09:23 AM More Dead Birds, Fish Idol Season 9: Top 4 -- Crystal Back Found Across The World in Action Recommend 65K Camille Grammer's Porn What's Your Reaction: Past Comes Back To Haunt Inspiring Funny Hot Scary Outrageous Amazing Weird Crazy Her Read More: Casey James , Crystal Bowersox , Ellen Degeneres , Kara DioGuardi , Lee Dewyze , Michael Like 689 Lynche , Movies , Pop Music , Randy Jackson , Reality TV , Ryan Seacrest , Simon Cowell , Entertainment News Elizabeth Edwards' Will It was movie night on American Idol and Crystal Revealed SHARE THIS STORY Bowersox appeared in her own production of A Star Is Recommend 533 (Re)Born. After a few weeks of showing "another side" to herself (sides that weren't that gripping), she got Intestinal Parasites May Be 0 back down to business with a bluesy spin on the 0 views 0 6 Causing Your Energy Kenny Loggins tune "I'm Alright" and a great duet Slump with Lee Dewyze on "Falling Slowly" from the indie Like 521 film Once. Any questions as to whether she would Get Entertainment Alerts make it to the winner's circle are over. Vegas, stop the Rudeness Is A Neurotoxin betting; Crystal will win it. -

Rca Records to Release American Idol: Greatest Moments on October 1

THE RCA RECORDS LABEL ___________________________________________ RCA RECORDS TO RELEASE AMERICAN IDOL: GREATEST MOMENTS ON OCTOBER 1 On the heels of crowning Kelly Clarkson as America's newest pop superstar, RCA Records is proud to announce the release of American Idol: Greatest Moments on Oct. 1. The first full-length album of material from Fox's smash summer television hit, "American Idol," will include four songs by Clarkson, two by runner-up Justin Guarini, a song each by the remaining eight finalists, and “California Dreamin’” performed by all ten. All 14 tracks on American Idol: Greatest Moments, produced by Steve Lipson (Backstreet Boys, Annie Lennox), were performed on "American Idol" during the final weeks of the reality-based television barnburner. In addition to Kelly and Justin, the show's remaining eight finalists featured on the album include Nikki McKibbon, Tamyra Gray, EJay Day, RJ Helton, AJ Gil, Ryan Starr, Christina Christian, and Jim Verraros. Producer Steve Lipson, who put the compilation together in an unprecedented two-weeks time, finds a range of pop gems on the album. "I think Kelly's version of ‘Natural Woman' is really strong. Her vocals are brilliant. She sold me on the song completely. I like Christina's 'Ain't No Sunshine.' I think she got the emotion of it across well. Nikki is very good as well -- very underestimated. And Tamyra is brilliant too so there's not much more to say about her." RCA Records will follow American Idol: Greatest Moments with the debut album from “American Idol” champion Kelly Clarkson in the first quarter of 2003.