By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

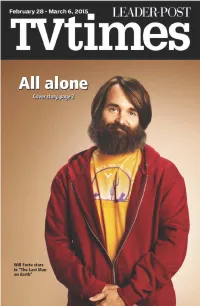

One and Only

Cover Story One and only Fox tackles the loneliest number in ‘The Last Man on Earth’ By Cassie Dresch people after a virus takes out him get into a lot of really silly TV Media all of Earth’s population. His shenanigans. family is gone, his coworkers “It’s all just kind of stupid ello? Hi? Anybody out are gone, the president is gone. stuff that I go around and do,” Hthere? Of course there is, Everyone. Gone. he said in an interview with otherwise life would be very, So what does he do? He “Entertainment Weekly.” very, very lonely. Fox is taking a travels the United States doing “That’s been one of the most stab at the ultimate life of lone- things he never would have fun parts of the job. About once liness in the new half-hour been able to do otherwise — a week I get to do something comedy “The Last Man on sing the national anthem at that seems like it’d be amaz- Earth,” premiering Sunday, Dodger Stadium, smear gooey ingly fun to do: shoot a flame March 1. peanut butter all over a price- thrower at a bunch of wigs, The premise around “Last less piece of art ... then walk have a steamroller steamroll Man” is a simple one, albeit a away with it, break things. The over a case of beer. Just dumb little strange. An average, un- show, according to creator and stuff like that, which pretty assuming man is on the hunt star Will Forte (“Saturday Night much is all it takes to make me for any signs of other living Live,” “Nebraska,” 2013), sees happy.” Registration $25.00 online: www.skseniorsmechanism.ca or phone 306-359-9956 2 Cover Story Flame throwers and steam- ally proud of what has come rollers? Again, it’s a strange out of it so far.” concept, but Fox is really be- Of course, you have to won- Index hind the show. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

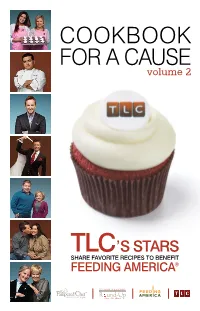

COOKBOOK for a CAUSE Volume 2

COOKBOOK FOR A CAUSE volume 2 TLC’S STARS SHARE FAVORITE RECIPES TO BENEFIT FEEDING AMERICA® FIGHTING HUNGER IN AMERICA ONE COOKBOOK at A TIME. The Pampered Chef® Cookbook for a Cause, Volume 2 benefits Feeding America®, the nation’s largest domestic hunger-relief organization. This year, the popular television network TLC® joined our mission to help fight hunger. TLC® stars from Cake Boss, Say Yes to the Dress, DC Cupcakes, The Little Couple, 19 Kids and Counting, What Not To Wear, and more, generously contributed their favorite recipes, in their own words. For each cookbook sold, we’ll donate $1 to Feeding America® to help provide eight meals to those in need.* We hope you’ll enjoy these recipes from the TLC® stars and the helpful tips and techniques from the experts in The Pampered Chef® Test Kitchens. As you gather around the table with family and friends, you can feel good that you’re helping another family in need to do the same. The Pampered Chef® The Pampered Chef® is the largest direct seller of everything you need to cook and entertain at home. At in-home Cooking Shows, guests see and try products, prepare and sample recipes, and learn quick and easy food preparation techniques and tips on how to entertain with style and ease — transforming the everyday into the extraordinary. TLC® is all about real-life reality, transporting the viewers into the lives of real-life extraordinary people with character. TLC® programs are entertaining, unfiltered and always reveal something worthwhile. TLC® is curious about people and finding the extraordinary in the everyday. -

Hearing Nostalgia in the Twilight Zone

JPTV 6 (1) pp. 59–80 Intellect Limited 2018 Journal of Popular Television Volume 6 Number 1 © 2018 Intellect Ltd Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/jptv.6.1.59_1 Reba A. Wissner Montclair State University No time like the past: Hearing nostalgia in The Twilight Zone Abstract Keywords One of Rod Serling’s favourite topics of exploration in The Twilight Zone (1959–64) Twilight Zone is nostalgia, which pervaded many of the episodes of the series. Although Serling Rod Serling himself often looked back upon the past wishing to regain it, he did, however, under- nostalgia stand that we often see things looking back that were not there and that the past is CBS often idealized. Like Serling, many ageing characters in The Twilight Zone often sentimentality look back or travel to the past to reclaim what they had lost. While this is a perva- stock music sive theme in the plots, in these episodes the music which accompanies the scores depict the reality of the past, showing that it is not as wonderful as the charac- ter imagined. Often, music from these various situations is reused within the same context, allowing for a stock music collection of music of nostalgia from the series. This article discusses the music of nostalgia in The Twilight Zone and the ways in which the music depicts the reality of the harshness of the past. By feeding into their own longing for the reclamation of the past, the writers and composers of these episodes remind us that what we remember is not always what was there. -

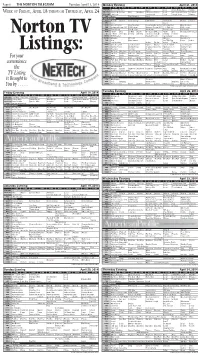

06 4-15-14 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2014 Monday Evening April 21, 2014 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline WEEK OF FRIDAY, APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY, APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS 2 Broke G Friends Mike Big Bang NCIS: Los Angeles Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson KSNK/NBC The Voice The Blacklist Local Tonight Show Meyers FOX Bones The Following Local Cable Channels A&E Duck D. Duck D. Duck Dynasty Bates Motel Bates Motel Duck D. Duck D. AMC Jaws Jaws 2 ANIM River Monsters River Monsters Rocky Bounty Hunters River Monsters River Monsters CNN Anderson Cooper 360 CNN Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront CNN Tonight DISC Fast N' Loud Fast N' Loud Car Hoards Fast N' Loud Car Hoards DISN I Didn't Dog Liv-Mad. Austin Good Luck Win, Lose Austin Dog Good Luck Good Luck E! E! News The Fabul Chrisley Chrisley Secret Societies Of Chelsea E! News Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Olbermann ESPN2 NFL Live 30 for 30 NFL Live SportsCenter FAM Hop Who Framed The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Step Brothers Archer Archer Archer Tomcats HGTV Love It or List It Love It or List It Hunters Hunters Love It or List It Love It or List It HIST Swamp People Swamp People Down East Dickering America's Book Swamp People LIFE Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Listings: MTV Girl Code Girl Code 16 and Pregnant 16 and Pregnant House of Food 16 and Pregnant NICK Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Friends Friends Friends SCI Metal Metal Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Metal Metal For your SPIKE Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Jail Jail TBS Fam. -

Beaver News, 50(18)

astic from and arry abed March 30 1976 Voume No 18 were ams ite Council announces Leres John Linnell underi the tweIvehour Big goes will thIy courses nder By Elaine Maiperson By Lotsa Morals The Graduate Council has an- the full time to explore all Dr John Linnell Dean of the new schedule for 300 and ramifications of an idea College recently announced his %el to into effect at courses go Mr Stewart registrar com intentions to aid Dr Edward Gates College in the fall of 1976 President of the in his at- mented Im excited about the way College ath course will be offered once to Beavers the new plan opens up the schedule tempt improve security for of twelve single period We will certainly have fewer con system Beaver security is from to This flicts next year Fhe graduate average just average merely will the to plan help college students like to consolidate then average Dean Linnell commented efficient of more use But we have to take look at what class time by making fewer trips to assroom space and of faculty time we arc and where were and the campus The new schedule will going Under the new instructors make system attract more graduate students As decision based upon how it II be able to teach at least four will affect the see it the only problem will be the entire College corn- aduate courses over and above weathcr One snow closing will munity Lr normal load of three un block out month of classes Dean Linnell has de ided that yrgrduat courses Now well be radically hargrg Bcavcr Litsa Marlos senior English to teach seven courses each security -

1 2019 Gally Academic Track Friday, February 15

2019 Gally Academic Track Friday, February 15, 2019 3:00-3:15 KEYNOTE “The Fandom Hierarchy: Women of Color’s Fight For Visibility In Fandom Spaces” Tai Gooden Women of Color (WoC) have been fervent Doctor Who fans for several decades. However, the fandom often reflects societal hierarchies upheld by White privilege that result in ignoring and diminishing WoC’s opinions, contributions, and legitimate concerns about issues in terms of representation. Additionally, WoC and non-binary (NB) people of color’s voices are not centered as often in journalism, podcasting, and media formats nor convention panels as much as their White counterparts. This noticeable disparity has led to many WoC, even those who are deemed “important” in fandom spaces, to encounter racism, sexism, and, depending on the individual, homophobia and transphobia in a place that is supposed to have open availability to everyone. I can attest to this experience as someone who has a somewhat heightened level of visibility in fandom as a pop culture/entertainment writer who extensively covers Doctor Who. This presentation will examine women of color in the Doctor Who fandom in terms of their interactions with non-POC fans and difficulties obtaining opportunities in media, online, and at conventions. The show’s representation of fandom and the necessity for equity versus equality will also be discussed to craft a better understanding of how to tackle this pervasive issue. Other actionable solutions to encourage intersectionality in the fandom will be discussed including privileged people listening to WoC and non- binary people’s concerns/suggestions, respectfully interacting with them online and in person, recognizing and utilizing their privilege to encourage more inclusivity, standing in solidarity with them on critical issues, and lending their support to WoC creatives. -

Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M

April 17 - 23, 2009 SPANISH FORK CABLE GUIDE 9 Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M. 4:30 5 P.M. 5:30 6 P.M. 6:30 7 P.M. 7:30 8 P.M. 8:30 9 P.M. 9:30 10 P.M. 10:30 11 P.M. 11:30 BASIC CABLE Oprah Winfrey Å 4 News (N) Å CBS Evening News (N) Å Entertainment Ghost Whisperer “Save Our Flashpoint “First in Line” ’ NUMB3RS “Jack of All Trades” News (N) Å (10:35) Late Show With David Late Late Show KUTV 2 News-Couric Tonight Souls” ’ Å 4 Å 4 ’ Å 4 Letterman (N) ’ 4 KJZZ 3The People’s Court (N) 4 The Insider 4 Frasier ’ 4 Friends ’ 4 Friends 5 Fortune Jeopardy! 3 Dr. Phil ’ Å 4 News (N) Å Scrubs ’ 5 Scrubs ’ 5 Entertain The Insider 4 The Ellen DeGeneres Show (N) News (N) World News- News (N) Two and a Half Wife Swap “Burroughs/Padovan- Supernanny “DeMello Family” 20/20 ’ Å 4 News (N) (10:35) Night- Access Holly- (11:36) Extra KTVX 4’ Å 3 Gibson Men 5 Hickman” (N) ’ 4 (N) ’ Å line (N) 3 wood (N) 4 (N) Å 4 News (N) Å News (N) Å News (N) Å NBC Nightly News (N) Å News (N) Å Howie Do It Howie Do It Dateline NBC A police of cer looks into the disappearance of a News (N) Å (10:35) The Tonight Show With Late Night- KSL 5 News (N) 3 (N) ’ Å (N) ’ Å Michigan woman. (N) ’ Å Jay Leno ’ Å 5 Jimmy Fallon TBS 6Raymond Friends ’ 5 Seinfeld ’ 4 Seinfeld ’ 4 Family Guy 5 Family Guy 5 ‘Happy Gilmore’ (PG-13, ’96) ›› Adam Sandler. -

B4 the MESSENGER, Friday, March 9, 2012 6:30 7:30 8:30 9:30

B4 B4 THE MESSENGER, Friday, March 9, 2012 03/9 6AM 6:30 7AM 7:30 8AM 8:30 9AM 9:30 10AM 10:30 11AM 11:30 WBKO ^ 5:30 AM Kentucky (N) Good Morning America Andrew Garfield; Richard Blais. (N) Å Live! With Kelly (N) Å The View (N) Å WBKO at Midday (N) % Today Kathy Bates; Elizabeth Olsen. (N) Å The 700 Club (N) Å WHAG News at 12:00PM (N) _ _ Paid Program Storm Stories Å Eyewitness News Daybreak (N) Local 7 News Lifestyles Family Feud Å Family Feud Å Animal Adv Å Swift Justice Å Judge Mathis Å 3 ( 5:00 The Daily Buzz Å Better (N) Å Cash Cab Å Cash Cab Å The Cosby Show Å The Cosby Show Å Law & Order: Criminal Intent Å C ) 5:00 QVC This Morning Perricone MD Cosmeceuticals Kitchen Innovations LizClaiborne New York Fashion. Q Check Style Edition . * 14 News Sunrise (N) Å Today Kathy Bates; Elizabeth Olsen. (N) Å Today (N) Å Today (N) Å :15 Midday With Mike (N) Å 9 + 5:00 Eyewitness News Daybreak (N) Å Good Morning America Andrew Garfield; Richard Blais. (N) Å Live! With Kelly (N) Å The View (N) Å FreeCruise Paid Program ) , Arthur (EI) Å Martha Speaks Å Curious George Å Cat in the Hat Å Super Why! Å Dinosaur Train Å Sesame Street (EI) Å Sid the Science Å WordWorld (EI) Å Super Why! Å Barney & Friends Å L ` Morning News Å Morning News Å CBS This Morning Ewan McGregor; Grant Hill. (N) Å The Doctors (N) Å The Price Is Right (N) Å The Young and the Restless (N) Å & 2 BBC World News Å Kentucky Health Å Body Electric Å TV 411 Å GED Connection Å GED Connection Å Paint This-Jerry Å Quilt in a Day Å Knitting Daily Å Beads, Baubles Å Charlie Rose Å WGN / Paid Program Paid Program Bewitched Å Dream of Jeannie Å Matlock “The Ghost” Å Matlock “The Class” Å In the Heat of the Night “Discovery” Å In the Heat of the Night Å INSP 1 Int’nl Fellowship Life Today Å Creflo Dollar Å Feed the Children Victory Today Life Today Å Joseph Prince Å Joyce Meyer Å Humanitarian Int’nl Fellowship The Waltons “The Idol” TBN 5 Spring Praise-A-Thon Spring Praise-A-Thon HGTV 7 Destination De Marriage/Const. -

How Superman Developed Into a Jesus Figure

HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE CRISIS ON INFINITE TEXTS: HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE By ROBERT REVINGTON, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Robert Revington, September 2018 MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2018) Hamilton, Ontario, Religious Studies TITLE: Crisis on Infinite Texts: How Superman Developed into a Jesus Figure AUTHOR: Robert Revington, B.A., M.A (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Travis Kroeker NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 143 ii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies LAY ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. It argues that this connection was not integral to the character as he was originally created, but was imposed by later writers over time and mainly for cinematic adaptations. This thesis also tracks the history of how Christians and churches viewed Superman, as the film studios began to exploit marketing opportunities by comparing Superman and Jesus. This thesis uses the methodological framework of intertextuality to ground its treatment of the sources, but does not follow all of the assumptions of intertextual theorists. iii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. Superman was created in 1938, but the character developed significantly from his earliest incarnations. -

Harris Sierra II, Programmable Cryptographic

TYPE 1 PROGRAMMABLE ENCRYPTION Harris Sierra™ II Programmable Cryptographic ASIC KEY BENEFITS When embedded in radios and other voice and data communications equipment, > Legacy algorithm support the Harris Sierra II Programmable Cryptographic ASIC encrypts classified > Low power consumption information prior to transmission and storage. NSA-certified, it is the foundation > JTRS compliant for the Harris Sierra II family of products—which includes two package options for the ASIC and supporting software. > Compliant with NSA’s Crypto Modernization Program The Sierra II ASIC offers a broad range of functionality, with data rates greater than 300 Mbps, > Compact form factor legacy algorithm support, advanced programmability and low power consumption. Its software programmability provides a low-cost migration path for future upgrades to embedded communications equipment—without the logistics and cost burden normally associated with upgrading hardware. Plus, it’s totally compliant with all Joint Tactical Radio System (JTRS) and Crypto Modernization Program requirements. The Sierra II ASIC’s small size, low power requirements, and high data rates make it an ideal choice for battery-powered applications, including military radios, wireless LANs, remote sensors, guided munitions, UAVs and any other devices that require a low-power, programmable solution for encryption. Specifications for: Harris SIERRA II™ Programmable Cryptographic ASIC GENERAL BATON/MEDLEY SAVILLE/PADSTONE KEESEE/CRAYON/WALBURN Type 1 – Cryptographic GOODSPEED Algorithms* ACCORDION FIREFLY/Enhanced FIREFLY JOSEKI Decrypt High Assurance AES DES, Triple DES Type 3 – Cryptographic AES Algorithms* Digital Signature Standard (DSS) Secure Hash Algorithm (SHA) Type 4 – Cryptographic CITADEL® Algorithms* SARK/PARK (KY-57, KYV-5 and KG-84A/C OTAR) DS-101 and DS-102 Key Fill Key Management SINCGARS Mode 2/3 Fill Benign Key/Benign Fill *Other algorithms can be added later. -

An Archeology of Cryptography: Rewriting Plaintext, Encryption, and Ciphertext

An Archeology of Cryptography: Rewriting Plaintext, Encryption, and Ciphertext By Isaac Quinn DuPont A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Information University of Toronto © Copyright by Isaac Quinn DuPont 2017 ii An Archeology of Cryptography: Rewriting Plaintext, Encryption, and Ciphertext Isaac Quinn DuPont Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Information University of Toronto 2017 Abstract Tis dissertation is an archeological study of cryptography. It questions the validity of thinking about cryptography in familiar, instrumentalist terms, and instead reveals the ways that cryptography can been understood as writing, media, and computation. In this dissertation, I ofer a critique of the prevailing views of cryptography by tracing a number of long overlooked themes in its history, including the development of artifcial languages, machine translation, media, code, notation, silence, and order. Using an archeological method, I detail historical conditions of possibility and the technical a priori of cryptography. Te conditions of possibility are explored in three parts, where I rhetorically rewrite the conventional terms of art, namely, plaintext, encryption, and ciphertext. I argue that plaintext has historically been understood as kind of inscription or form of writing, and has been associated with the development of artifcial languages, and used to analyze and investigate the natural world. I argue that the technical a priori of plaintext, encryption, and ciphertext is constitutive of the syntactic iii and semantic properties detailed in Nelson Goodman’s theory of notation, as described in his Languages of Art. I argue that encryption (and its reverse, decryption) are deterministic modes of transcription, which have historically been thought of as the medium between plaintext and ciphertext.