Hearing Nostalgia in the Twilight Zone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

How Superman Developed Into a Jesus Figure

HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE CRISIS ON INFINITE TEXTS: HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE By ROBERT REVINGTON, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Robert Revington, September 2018 MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2018) Hamilton, Ontario, Religious Studies TITLE: Crisis on Infinite Texts: How Superman Developed into a Jesus Figure AUTHOR: Robert Revington, B.A., M.A (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Travis Kroeker NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 143 ii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies LAY ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. It argues that this connection was not integral to the character as he was originally created, but was imposed by later writers over time and mainly for cinematic adaptations. This thesis also tracks the history of how Christians and churches viewed Superman, as the film studios began to exploit marketing opportunities by comparing Superman and Jesus. This thesis uses the methodological framework of intertextuality to ground its treatment of the sources, but does not follow all of the assumptions of intertextual theorists. iii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. Superman was created in 1938, but the character developed significantly from his earliest incarnations. -

Season 5 Article

N.B. IT IS RECOMMENDED THAT THE READER USE 2-PAGE VIEW (BOOK FORMAT WITH SCROLLING ENABLED) IN ACROBAT READER OR BROWSER. “EVEN’ING IT OUT – A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE LAST TWO YEARS OF “THE TWILIGHT ZONE” Television Series (minus ‘THE’)” A Study in Three Parts by Andrew Ramage © 2019, The Twilight Zone Museum. All rights reserved. Preface With some hesitation at CBS, Cayuga Productions continued Twilight Zone for what would be its last season, with a thirty-six episode pipeline – a larger count than had been seen since its first year. Producer Bert Granet, who began producing in the previous season, was soon replaced by William Froug as he moved on to other projects. The fifth season has always been considered the weakest and, as one reviewer stated, “undisputably the worst.” Harsh criticism. The lopsidedness of Seasons 4 and 5 – with a smattering of episodes that egregiously deviated from the TZ mold, made for a series much-changed from the one everyone had come to know. A possible reason for this was an abundance of rather disdainful or at least less-likeable characters. Most were simply too hard to warm up to, or at the very least, identify with. But it wasn’t just TZ that was changing. Television was no longer as new a medium. “It was a period of great ferment,” said George Clayton Johnson. By 1963, the idyllic world of the 1950s was disappearing by the day. More grittily realistic and reality-based TV shows were imminent, as per the viewing audience’s demand and it was only a matter of time before the curtain came down on the kinds of shows everyone grew to love in the 50s. -

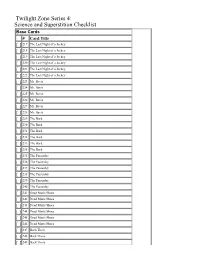

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 217 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 218 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 219 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 220 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 221 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 222 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 223 Mr. Bevis [ ] 224 Mr. Bevis [ ] 225 Mr. Bevis [ ] 226 Mr. Bevis [ ] 227 Mr. Bevis [ ] 228 Mr. Bevis [ ] 229 The Bard [ ] 230 The Bard [ ] 231 The Bard [ ] 232 The Bard [ ] 233 The Bard [ ] 234 The Bard [ ] 235 The Passersby [ ] 236 The Passersby [ ] 237 The Passersby [ ] 238 The Passersby [ ] 239 The Passersby [ ] 240 The Passersby [ ] 241 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 242 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 243 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 244 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 245 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 246 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 247 Back There [ ] 248 Back There [ ] 249 Back There [ ] 250 Back There [ ] 251 Back There [ ] 252 Back There [ ] 253 The Purple Testament [ ] 254 The Purple Testament [ ] 255 The Purple Testament [ ] 256 The Purple Testament [ ] 257 The Purple Testament [ ] 258 The Purple Testament [ ] 259 A Piano in the House [ ] 260 A Piano in the House [ ] 261 A Piano in the House [ ] 262 A Piano in the House [ ] 263 A Piano in the House [ ] 264 A Piano in the House [ ] 265 Night Call [ ] 266 Night Call [ ] 267 Night Call [ ] 268 Night Call [ ] 269 Night Call [ ] 270 Night Call [ ] 271 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 272 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 273 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 274 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 275 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 276 A Hundred -

Potomacpotomac Page 10

Wellbeing PotomacPotomac Page 10 Growing News, Page 2 Real Estate 8 Real Estate ❖ Classifieds, Page 11 Classifieds, ❖ Calendar, Page 6 Calendar, Bravo To Present ‘Annie Jr.’ And ‘Legally Blonde Jr.’ News, Page 3 Become a Court-Appointed Advocate for Children News, Page 3 Keeping Resolutions Wellbeing, Page 10 Photo Contributed Photo January 4-10, 2017 online at potomacalmanac.com www.ConnectionNewspapers.com Potomac Almanac ❖ January 4-10, 2017 ❖ 1 News Lower School Principal Margaret Andreadis with students. Bullis School second graders on a canoe trip encounter a frog. Bullis School To Add Kindergarten and First Grade To begin in the abstract, to develop good numerical sense and to communicate in speaking and September. writing. I teach the kids to select good books By Susan Belford and to read independently. I love experien- The Almanac tial learning and taking them to the C&O Canal to really experience nature, ecology ow far The Bullis School has and to appreciate the outdoors. I believe come since it was launched in that learning should be fun, engaging and H1930 as a one-year prepara- challenging and that the students should tory boarding school for high have the opportunity to be active agents in school graduates. Initially founded to pre- their learning.” pare young men for service academy en- He added, “Teaching this age group is trance exams, it opened in the former Bo- exhilarating because there is an incredible livian Embassy at 1303 New Hampshire range among the kids and the children are Ave. As enrollment increased, Bullis relo- so different from the beginning of the year cated in 1935 to the “country setting” of to the end. -

Production Notes

PUBLICITY CONTACTS LA NATIONAL Karen Paul Anya Christiansen Chris Garcia – 42 West (310) 575-7033 (310) 575-7028 (424) 901-8743 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] NY NATIONAL Sara Groves – 42 West Tom Piechura – 42 West Jordan Lawrence – 42 West (212) 774-3685 (212) 277-7552 (646) 254-6020 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] REGIONAL Gillian Fischer Linda Colangelo (310) 575-7032 (310) 575-7037 [email protected] [email protected] DIGITAL Matt Gilhooley Grey Munford (310) 575-7024 (310) 575-7425 [email protected] [email protected] Release Date: May 31, 2013 (Limited) Run Time: 92 Minutes For all approved publicity materials, visit www.cbsfilmspublicity.com THE KINGS OF SUMMER Preliminary Production Notes Synopsis Premiering to rave reviews at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival, THE KINGS OF SUMMER is a unique coming-of-age comedy about three teenage friends – Joe (Nick Robinson), Patrick (Gabriel Basso) and the eccentric and unpredictable Biaggio (Moises Arias) - who, in the ultimate act of independence, decide to spend their summer building a house in the woods and living off the land. Free from their parents’ rules, their idyllic summer quickly becomes a test of friendship as each boy learns to appreciate the fact that family - whether it is the one you’re born into or the one you create – is something you can't run away from. ABOUT THE PRODUCTION The Kings of Summer began in the imagination of writer Chris Galletta, who penned his script during his off hours while he was working in the music department of “The Late Show with David Letterman.” After some false starts in screenwriting, Galletta shunned his impulse to write a high-concept tentpole feature and craft something more character-driven and personal. -

Poetry Prose

CONTEMPORARY POETRY AND PROSE Poems by Wallace Stevens Dylan Thomas E. E. Cummings Gavin Ewart Kerker Quinn Ruthven Todd Kenneth Allott Roger Roughton Short Story by Isaac Babel A Labrador Ballad - An Appalachian Ballad A Greenland Folk-Legend July 1936. Monthly. Sixpence CONTEMPORARY POETRY AND PROSE July 1936 Monthly Sixpence CONTENTS POEM E. E. Cummings THREE POEMS Kenneth Allott FAREWELL TO FLORIDA Wallace Stevens Two POEMS TOWARDS A POEM Dylan Thomas DOLLFUSS DAY, 1935 Gavin Ewart WORM INTERVIEWED Ruthven Todd MAKING FEET AND HAND,S Benjamin Peret MORALITY PLAY Kerker Quinn SOLUBLE NOUGHTS AND CROSSES; or, CALIFORNIA, HERE I COME Roger Roughton THE BALLAD OF Miss COLMAN (Anon) THE PROUD LAMKIN (Anon) NUKARPIARTEKAK (Anon) IN THE BASEMENT Isaac Babel Poem by E. E. Cummings little joe gould Has lost his teeth and doesn't know where to find them (and found a secondhand set which click)'little gould used to amputate his appetite with bad brittle candy but just (nude eel) now little joe lives on air Harvard Brevis Est for Handkerchief read Papernapkin no laundry bills likes People preferring Negroes Indians Youse n.b. ye twang of -little joe (yankee) gould irketh sundry who are trying to find their minds (but never had any to lose) and a myth is as good as a smile but little joe gould's quote oral history unquote might (publishers note) be entitled a wraith's progress or mainly awash while chiefly submerged or an amoral morality sort-of-aliveing by innumerable kind-of-deaths (Amerique Je T'Aime and it may be fun to be fooled but it's more fun to be more to be fun to be little joe gould) Three Poems by Kenneth Allott Decor The shunting of course goes on all day and night the coupling, the buffers, the points, the hammering the ever-open door of all-night kitchen (Everything here is fresh every day your lordship.) and the great arc lights splutter every night and the trains are very tiresome with their blue flashes the small hours, all night and every night. -

Fade In: Int. Art Gallery – Day

FADE IN: INT. ART GALLERY – DAY Exhibition Guide FADE IN: INT. ART GALLERY – DAY March 03 – May 08, 2016 Works by Danai Anesiadou, Nairy Baghramian, Michael Bell-Smith, Dora Budor, Heman Chong, Mike Cooter, Brice Dellsperger, GALA Committee, Mathis Gasser, Jamian Juliano-Villani, Bertrand Lavier, William Leavitt, Christian Marclay, Rodrigo Matheus, Allan McCollum, Henrique Medina, Carissa Rodriguez, Cindy Sherman, Amie Siegel, Scott Stark, and Albert Whitlock; performances and public programs by Casey Jane Ellison, Mario García Torres, Alex Israel, Thirteen Black Cats, and more. Recasting the gallery as a set for dramatic scenes, FADE IN: INT. ART GALLERY – DAY explores the role that art plays in narrative film and television. FADE IN features the work of 25 artists and considers a history of art as seen in classic movies, soap operas, science fiction, pornography and musicals. These works have been sourced, reproduced and created in response to artworks that have been made to appear on-screen, whether as props, set dressings, plot devices, or character cues. The nature of the exhibition is such that sculptures, paintings and installations transition from prop to image to art object, staging an enquiry into whether these fictional depictions in mass media ultimately have greater influence in defining a collective understanding of art than art itself does. Certain preoccupations with artworks are established early on in cinematic history: the preciousness of art objects anchors their roles as plot drivers, and anxieties intensify regarding the vitality of artworks and their perceived abilities to wield power over viewers or to capture spirits. Such themes were famously explored in the 1945 film adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, from which Cindy Sherman has sourced the original portrait painted for the production. -

The Republican Journal Vol. 87, No. 12

Today’s Journal. of A flock of ents _-- UB1TUARY. large wild geese flew over Belfast W“8 News of Belfast last the Granges. .Obituary... much respected, and The bay Monday afternoon—another sign of PERSONAL” PERSONAL. had many frienda societies. .The News of Bel- It was with a shock and sense of loss that in Pittsfield and eurround- spring. The War News... the friends in .ng owns who extend crePersonal.. Belfast learned of the death in sympathy to those who THE MARCH WIND. Mr. J. W. Roberts writes from Mrs. E. 0. Clement of Wedding Bells, «e left Reading. Mrs. John O. Black is her mother Pittsfield is visiting flections.. March of to mourn their visiting in sln Boston, I8th, Miss Clara Prentiss loss, Mr. was The March wind is a saucy sprite, Mass: “Have returned relatives in Pacific Exposition. .One Bagle, just from Orlando and Union. Montville. '^r-.iiiiina Parsons. She had been ill some Bnd i8 He blows skirts awry Another. .A weeks, but survived by a widow, girls’ St. Augustine, Florida, where we met Suggests Mrs down the some Emerton Gross has returned from Sconce was to be Mr'eJn!'1",edNell,e W. And sends bats rolling street, Miss Bernice Holt returned from Camden, Letter. .Recent Deaths. supposed improving slowly, when Bagley. with whom he was Belfast people.*' Monday ^,r united in To cheer the passers-by. where he spent the week's school vacation with on March 10th a sudden marriage about Warren, where she spent the Easter recess. ... \ew York. .Shamrocks at change for the worse years dust thin,-five ago, He fills the air with blinding We have received an hie A. -

There Is No Time Like the Past Retro Between Memory and Materiality in Contemporary Culture Handberg, Kristian

There is no time like the past Retro between memory and materiality in contemporary culture Handberg, Kristian Publication date: 2014 Document version Early version, also known as pre-print Citation for published version (APA): Handberg, K. (2014). There is no time like the past: Retro between memory and materiality in contemporary culture. Det Humanistiske Fakultet, Københavns Universitet. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 FACULTY OF HUMANITIES UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN PhD thesis Kristian Handberg There’s no time like the past Retro between memory and materiality in contemporary culture Academic advisor: Mette Sandbye Submitted: 09/05/2014 Institutnavn: Institut for Kunst og Kulturvidenskab Name of department: Department of Arts and Cultural Studies Author: Kristian Handberg Titel og evt. undertitel: There´s no time like the past Title / Subtitle: Retro between memory and materiality in contemporary culture Subject description: A study of retro in contemporary culture as cultural memory through analyses of site-specific contexts of Montreal and Berlin. Academic advisor: Mette Sandbye, lektor, Institut for Kunst og Kulturvidenskab, Københavns Universitet. Co-advisor: Will Straw, Professor, McGill University, Montreal, Canada. Submitted: May 2014 2 Contents AKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................... 6 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 7 There’s no time like the past: Presenting the project -

TWILIGHT ZONE Di Fabio Giovannini

ROD SERLING’S THE TWILIGHT ZONE di Fabio Giovannini “C’è una quinta dimensione, oltre a quelle conosciute dall’uomo: è una dimensione grande come lo spazio e smisurata come l’infinito, è a mezza strada fra la luce e l’ombra, fra la scienza e la superstizione, fra la sommità delle cognizioni dell’Uomo ed il fondo dei suoi smarrimenti. È la dimensione della fantasia, è una zona che noi chiamiamo: ‘Il confine della realtà’. Dal 1959 milioni di schermi televisivi hanno trasmesso queste parole introduttive per una serie di telefilm che prometteva di condurre lo spettatore nella “quinta dimensione”. Le pronunciava, almeno nella versione originale americana, un serio personaggio dal naso schiacciato, Rod Serling. Nel 1959, quando iniziò The Twilight zone, era un personaggio del tutto sconosciuto, ma dopo un solo anno gli americani riconoscevano immediatamente la voce e i tratti di questo ospite che accompagnava nel territorio tra la luce e le tenebre, tra la scienza e la superstizione. Rod Serling in Italia non ha avuto alcuna fama, ma le sue parole “introduttive” sono egualmente entrate nelle tranquille case del bel- paese, per qualche anno. Le persone normali di Ai confini della realtà sempre precipitate in situazioni straordinarie, erano cesellate sul modello del cittadino medio statunitense, ma anche l’uomo comune italiano poteva identificarsi nelle fobie umane portate agli eccessi dall’abile Rod Serling. Twilight Zone (letteralmente la zona del crepuscolo) il serial televisivo che in Italia è stato trasmesso dalla RAI all’inizio degli anni Sessanta con il titolo Ai confini della realtà è stata la più lunga serie Tv di argomento fantastico prodotta negli Stati Uniti, se si eccettua la soap-opera Dark Shadows (le avventure del vampiro buono Barnabas Collins). -

The Philosophy of the Western

University of Kentucky UKnowledge American Popular Culture American Studies 5-28-2010 The Philosophy of the Western Jennifer L. McMahon East Central University B. Steve Csaki Centre College Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation McMahon, Jennifer L. and Csaki, B. Steve, "The Philosophy of the Western" (2010). American Popular Culture. 11. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_american_popular_culture/11 (CONTINUED FROM FRONT FLAP) McMAHON PHILOSOPHY/FILM AND CSAKI THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE gender, animal rights, and other topics depicted in western narratives. “The writing is accessible to nonspecialists and should be of interest to general WESTERN Drawing from philosophers as varied as Aristotle, Spinoza, William James, and Jean- readers who enjoy thinking about EDITED BY Paul Sartre, The Philosophy of the Western JENNIFER L. McMAHON AND B. STEVE CSAKI examines themes that are central to the genre: philosophy, film, or westerns.” individual freedom versus community; the —KAREN D. HOFFMAN, encroachment of industry and development on the natural world; and the epistemological Hood College here are few film and television genres and ethical implications of the classic “lone that capture the hearts of audiences rider” of the West. The philosophies of John like the western. While not always T T Locke, Thomas Hobbes, and Jean-Jacques H true to the past, westerns are tied to, and Rousseau figure prominently in discussions E P expressive of, the history of the United States.