INSTITUTION Congress of the US, Washington, DC. House Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Ball! One of the Most Recognizable Stars on the U.S

TVhome The Daily Home June 7 - 13, 2015 On the Ball! One of the most recognizable stars on the U.S. Women’s World Cup roster, Hope Solo tends the goal as the U.S. 000208858R1 Women’s National Team takes on Sweden in the “2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup,” airing Friday at 7 p.m. on FOX. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., June 7, 2015 — Sat., June 13, 2015 DISH AT&T CABLE DIRECTV CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA SPORTS BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING 5 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 Championship Super Regionals: Drag Racing Site 7, Game 2 (Live) WCIQ 7 10 4 WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Monday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 8 p.m. ESPN2 Toyota NHRA Sum- 12 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 mernationals from Old Bridge Championship Super Regionals Township Race. -

Hearing Nostalgia in the Twilight Zone

JPTV 6 (1) pp. 59–80 Intellect Limited 2018 Journal of Popular Television Volume 6 Number 1 © 2018 Intellect Ltd Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/jptv.6.1.59_1 Reba A. Wissner Montclair State University No time like the past: Hearing nostalgia in The Twilight Zone Abstract Keywords One of Rod Serling’s favourite topics of exploration in The Twilight Zone (1959–64) Twilight Zone is nostalgia, which pervaded many of the episodes of the series. Although Serling Rod Serling himself often looked back upon the past wishing to regain it, he did, however, under- nostalgia stand that we often see things looking back that were not there and that the past is CBS often idealized. Like Serling, many ageing characters in The Twilight Zone often sentimentality look back or travel to the past to reclaim what they had lost. While this is a perva- stock music sive theme in the plots, in these episodes the music which accompanies the scores depict the reality of the past, showing that it is not as wonderful as the charac- ter imagined. Often, music from these various situations is reused within the same context, allowing for a stock music collection of music of nostalgia from the series. This article discusses the music of nostalgia in The Twilight Zone and the ways in which the music depicts the reality of the harshness of the past. By feeding into their own longing for the reclamation of the past, the writers and composers of these episodes remind us that what we remember is not always what was there. -

Breast Implants: Choices Women Thought They Made

NYLS Journal of Human Rights Volume 11 Issue 1 Article 5 Fall 1993 BREAST IMPLANTS: CHOICES WOMEN THOUGHT THEY MADE Zoe Panarites Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/journal_of_human_rights Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Panarites, Zoe (1993) "BREAST IMPLANTS: CHOICES WOMEN THOUGHT THEY MADE," NYLS Journal of Human Rights: Vol. 11 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/journal_of_human_rights/vol11/iss1/5 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Journal of Human Rights by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. BREAST IMPLANTS: CHOICES WOMEN THOUGHT THEY MADE Nearly two million women- received breast implants between 1962 and 1991: eighty percent for cosmetic purposes, and twenty percent for reconstructive surgery following mastectomies. 1 From their inauspicious beginnings as a tool for Japanese prostitutes during World War II to enlarge their breasts for American servicemen, 2 implants have now been deemed crucial to post-mastectomy recipients3 and other women seeking self-improvement." Implants are © Copyright 1993 by the New York Law School Journalof Human Rights. 'John R. Easter ct al., Medical "State of the Art"for the Breast Implant Litigation, in BREAST IMPLANT Lrrio. 1, 12 (Law Journal Seminars-Press 1992). This Note will focus primarily on silicone-filled implants. Food and Drug Administration ("FDA") estimates released in 1988 indicate that only 15% of implant surgeries were for reconstructive purposes, while 85% were for cosmetic purposes. Teich v. FDA, 751 F. Supp. 243, 245-46 (D.D.C. -

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

History of Radio Broadcasting in Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1963 History of radio broadcasting in Montana Ron P. Richards The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Richards, Ron P., "History of radio broadcasting in Montana" (1963). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5869. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5869 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HISTORY OF RADIO BROADCASTING IN MONTANA ty RON P. RICHARDS B. A. in Journalism Montana State University, 1959 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY 1963 Approved by: Chairman, Board of Examiners Dean, Graduate School Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number; EP36670 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Oiuartation PVUithing UMI EP36670 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). -

Clowning with Kids' Health – the Case for Ronald Mcdonald's

Brought To You By: and its campaign Clowning With Kids’ Health THE CASE FOR RONALD MCDONALD’S RETIREMENT www.RetireRonald.org Table of Contents FOREWORD ....................................................................................... Page 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. Page 2 RONALD MCDONALD: A RETROSPECTIVE .......................................... Page 4 Birth of a pioneer…in marketing to kids ................................................ Page 5 Clown at a crossroads ........................................................................ Page 6 Where’s RONALD? ........................................................................... Page 7 What did Americans find? .................................................................... Page 8 Clowning around schools .................................................................... Page 8 McSpelling and Teaching .................................................................... Page 10 The Ironic Ronald McJock .................................................................... Page 11 Providing his own brand of healthcare ................................................... Page 12 Taking to the tube .............................................................................. Page 13 The McWorld Wide Web ....................................................................... Page 14 PUTTING RONALD ON KIds’ BraINS, PAST PARENTS ......................... Page 15 The power of getting the brand in kids’ hands -

A Guide for Educators to Support the Weekend Morning TV Series

A Guide for Educators to Support the Weekend Morning TV Series TO EDUCATORS AND PARENTS "The All New Captain Kangaroo"—A Guide for Educators is designed to help educators and parents locate the educational components of each episode. The Storybook Corner section (page 4) includes a list of storybook titles that Captain Kangaroo will read throughout the CAPTAIN KANGAROO season—all of which tie into the theme of each episode. The grid (pages 14-15) will allow the Presented by Saban Entertainment, CURRICULUM AREAS reader to view the theme, manner/civility Inc., in association with Reading Music, Art, Science, lesson, educational goal Is Fundamental® and The America Reading and Language Arts and learning objective, Reads Challenge AGE LEVELS as well as the focus of Ages 2-5 the Nature/Animal and & Storybook Corner he Captain is back! Captain Kangaroo, GRADE LEVELS segments, for each beloved icon of children's programming Pre-Kindergarten, episode. Tand television figure with whom millions Kindergarten of kids grew up, returns to usher a new gener * "The All New ation into a new millennium. EDUCATIONAL GOALS Captain Kangaroo" "The All New Captain Kangaroo" blends • To promote self-esteem, will trigger meaningful the best of the original show with new educa cooperative, pro-social classroom discussions tional goals and characters to create a fun, behavior and a positive "The All New Captain Kangaroo" or activities that are exciting and educational TV experience. attitude. airs weekly nationwide on Saturday sure to build and Veteran actor John McDonough, who has • To introduce the impor or Sunday morning. strengthen character. -

Spring/Summer 2019

34 We are dedicated to improving the health and How Can We Cut the Cost of Medical Care? safety of adults and children by using research to develop Everyone agrees that health insurance is too Our own research on cancer drugs found that expensive and prescription drugs cost much too many that were recently approved based on their more effective treatments and much – some cost more than patients’ annual success at shrinking tumors provided zero benefit income! The amount Americans spend on to the average patient in terms of living longer or policies. The Cancer prescription drugs has nearly doubled since the having a better quality of life. Since cancer drugs Prevention and Treatment 1990s, and today the most expensive drugs cost so often cause nausea, vomiting, exhaustion, and $500,000 or more per year. other debilitating side effects, it is unconscionable Fund is our major program. that these drugs are being approved without clear What’s the solution? evidence that they work – or which patients have at least some chance of benefitting even if most This article isn’t about Medicare for All, Medicaid don’t. for All, or other major legislation, all of which face enormous political and corporate opposition. Instead, this article focuses on the issues that would be easier to fix in the near term. How to Spend Less on Drugs and Medical Tests Too many patients are being priced out of the Our Cancer Prevention and medical treatment that they need – or think they Treatment Fund helps adults need. As prices have risen, companies have broken one record after another, so that it seems there is and children reduce their risk no limit on what they will charge. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

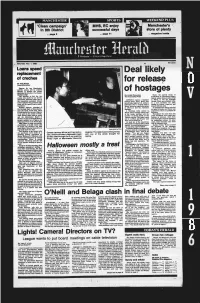

Deal Likely for Release of Hostag^

MANCHESTER ‘Glean campaign’ MHS, EC enjoy Manchester's \ in 9th District successful days i f " store of plenty ... page 3 ... page 11 r ... magatine Inside iManrlipatpr HpralJi Manchester — A City of Village Charm 30 Cents Saturday, Nov. 1,1986 N Loans sjseed replacement Deal likely of creches for release By Alex GIrelll Associate Editor Figures for two Manchester nativity scenes will be ordered Monday to repiace two scenes of h o s ta g ^ destroyed by fire Oct. 17 at Center Springs Lodge. By Joseph Panosslan Waite, the special envoy of The decision to buy the two The Associated Press Archbishop of Canterbury Robert^ scenes was made by an ad hoc Runcie. made three previous trips V committee Thursday after two of LARNACA. Cyprus — Anglican to Beirut to win the hostages the committee members offered Church envoy Terry Waite flew release. Waite was whisked away loans to finance the purchases. The here Friday night by U.S. military in a U.S. Embassy car after loans will be repaid from a public helicopter after a surprise visit to landing in Cyprus, reporters and fund drive. Beirut, where he reported progress airport officials said. William Johnson, president of in efforts to free the American An immigration official who did the Savings Bgnk of Manchester, hostages. not give his name said Waite was said the bank wouid loan about A Christian radio station in , expected to return to Lebanon on $10,000 needed for one set of figures Beirut said a hostage release was ' Saturday. to be used in the center of town, in the works, starting with the Throughout the more than two while Daniel Reale said he would transfer to Syrian hands of two years foreigners have been held ask the Manchester Board of French captives. -

How Superman Developed Into a Jesus Figure

HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE CRISIS ON INFINITE TEXTS: HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE By ROBERT REVINGTON, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Robert Revington, September 2018 MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2018) Hamilton, Ontario, Religious Studies TITLE: Crisis on Infinite Texts: How Superman Developed into a Jesus Figure AUTHOR: Robert Revington, B.A., M.A (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Travis Kroeker NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 143 ii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies LAY ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. It argues that this connection was not integral to the character as he was originally created, but was imposed by later writers over time and mainly for cinematic adaptations. This thesis also tracks the history of how Christians and churches viewed Superman, as the film studios began to exploit marketing opportunities by comparing Superman and Jesus. This thesis uses the methodological framework of intertextuality to ground its treatment of the sources, but does not follow all of the assumptions of intertextual theorists. iii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. Superman was created in 1938, but the character developed significantly from his earliest incarnations. -

Exposing Corruption in Progressive Rock: a Semiotic Analysis of Gentle Giant’S the Power and the Glory

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 EXPOSING CORRUPTION IN PROGRESSIVE ROCK: A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF GENTLE GIANT’S THE POWER AND THE GLORY Robert Jacob Sivy University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2019.459 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Sivy, Robert Jacob, "EXPOSING CORRUPTION IN PROGRESSIVE ROCK: A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF GENTLE GIANT’S THE POWER AND THE GLORY" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 149. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/149 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known.