Season 5 Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gogebic Courts Receive High Marks

Call (906) 932-4449 Ironwood, MI Badger brothers Hurley grads Mark and Jacob Redsautosales.com reflect on Wisconsin season SPORTS • 6 DAILY GLOBE Friday, February 1, 2019 Mostly cloudy yourdailyglobe.com | High: 15 | Low: 7 | Details, page 2 Gogebic courts receive high marks BESSEMER – The pub- ing us make decisions on and focused on improving users said they were: treat- agement decisions that tiative of the Michigan lic continues to be satisfied how to improve court oper- service to the public.” ed with respect, the judge help better serve the pub- Supreme Court and State with Gogebic County’s ations,” Chief Judge The survey was part of a or magistrate handled their lic,” Court Administrator Court Administrative court system, awarding it Michael Pope said in a statewide effort and asked case fairly, able to get their Susan Mitchem said in the Office has included more high marks for the fifth news release. “I am very court users such as parties business done in a reason- release. “Our goal is for than 120,000 surveys year in a row in a survey proud of the hard work put to cases, attorneys and able amount of time and every person who comes throughout the state regarding user experience. in by our teams in all of our jurors whether the courts understood the proceed- through the courthouse between 2013 and 2018. “Our courts serve the courts in Gogebic County, were accessible, timely, fair ings as they left the courts. doors to be satisfied and Visit courts.mi.gov for people, so their views are and we are committed to and how they were treated. -

Senior Women's Performances of Sexuality

“DUSTY MUFFINS”: SENIOR WOMEN’S PERFORMANCES OF SEXUALITY A Thesis by EVLEEN MICHELLE NASIR Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2012 Major Subject: Performance Studies “Dusty Muffins”: Senior Women’s Performances of Sexuality Copyright 2012 Evleen Michelle Nasir “DUSTY MUFFINS”: SENIOR WOMEN’S PERFORMANCES OF SEXUALITY A Thesis by EVLEEN MICHELLE NASIR Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved by: Chair of Committee, Kirsten Pullen Committee Members, Judith Hamera Harry Berger Alfred Bendixen Head of Department, Judith Hamera August 2012 Major Subject: Performance Studies iii ABSTRACT “Dusty Muffins”: Senior Women’s Performance of Sexuality. (August 2012) Evleen Michelle Nasir, B.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Kirsten Pullen There is a discursive formation of incapability that surrounds senior women’s sexuality. Senior women are incapable of reproduction, mastering their bodies, or arousing sexual desire in themselves or others. The senior actresses’ I explore in the case studies below insert their performances of self and their everyday lives into the large and complicated discourse of sex, producing a counter-narrative to sexually inactive senior women. Their performances actively embody their sexuality outside the frame of a character. This thesis examines how senior actresses’ performances of sexuality extend a discourse of sexuality imposed on older woman by mass media. These women are the public face of senior women’s sexual agency. -

Arisia 2010 Pocket Program

Maps Quick Ref ARISIA 2011 Main Events Dealers January 14-17 ARISIA BOSTON 2010 Friday NEW LOCATION: Westin Boston Saturday Waterfront Hotel $130/night Sunday Monday Participant Schedules Fan GoH: RenŽ Walling Artist GoH: Josh Simpson Writer GoH: Kelley Armstrong POCKET PROGRAM Webcomic GoH: Shaenon Garrity Pre-Registration $25 until 2010-01-20 B 1st Floor Paul MAPS HOTEL Revere Garage A Main Program Ops Entrance Masquerade, Bone Marrow & Blood Drive President’s CD Gift Sign-ups Fan Tables Shop D Registration Crispus Attucks William Dawes Molly Pitcher Business Center A B Info Desk BC Elevators Arisia Sales Prefunction Thomas Paine Haym President’s B President’s A Solomon Coat Food Cart Check A Front Desk EscalatorsBathrooms Bridge to Garage/ Health Club 2nd Floor (stairs) 201 202 203 204 205 Rooms 207–223 Volunteer Lounge Bathrooms Elevators Aquarium Cambridge Rooms 212–224 Con Ops Atrium & Security Con Suite MAPSHOTEL Escalators Hotel Area Zephyr Patio No access Crow’s Nest: 3rd floor Atrium to Lobby Dealers’ Row: 3rd floor BU Lounge: 10th floor Zephyr Fast Track: Empress (14th floor) Rooms 237–256 Restaurant & Bar Art Show: Charles View (16th floor) QUICK REFERENCE QUICK REFERENCE Access/Handicapped Services go to Information Desk Filk (all night) Crispus Attucks Anime Room Haym Solomon Friday–Sunday 11pm–late Fri/Sat/Sun 7pm–6am Monday after teardown Arisia TV Channel 41 Films Molly Pitcher Movies, live ballroom events, etc. Friday 4pm–1am SciFi Channel replaces BBC channel for the con. Saturday 7pm–1am Art Show Charles View (16th floor) Sunday 6pm–1am Monday 9am–11am (audience choice vote 9am sharp) Friday 6pm–9pm Food Options Saturday 10am–8pm Sunday 10am–8pm Hotel Restaurant on second floor. -

Super! Drama TV April 2021

Super! drama TV April 2021 Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2021.03.29 2021.03.30 2021.03.31 2021.04.01 2021.04.02 2021.04.03 2021.04.04 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 #15 #17 #19 #21 「The Long Morrow」 「Number 12 Looks Just Like You」 「Night Call」 「Spur of the Moment」 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 #16 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 「The Self-Improvement of Salvadore #18 #20 #22 Ross」 「Black Leather Jackets」 「From Agnes - With Love」 「Queen of the Nile」 07:00 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK Season 1 07:00 THUNDERBIRDS 07:00 #1 #2 #20 #19 「X」 「Burn」 「Court Martial」 「DANGER AT OCEAN DEEP」 07:30 07:30 07:30 08:00 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 08:00 ULTRAMAN towards the future 08:00 THUNDERBIRDS 08:00 10 10 #1 #20 #13「The Romance Recalibration」 #15「The Locomotion Reverberation」 「bitter harvest」 「MOVE- AND YOU'RE DEAD」 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 10 #14「The Emotion Detection 10 12 Automation」 #16「The Allowance Evaporation」 #6「The Imitation Perturbation」 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:30 09:30 THE GREAT 09:30 SUPERNATURAL Season 14 09:30 09:30 BETTER CALL SAUL Season 3 09:30 ZOEY’S EXTRAORDINARY -

1.50 Whitham

f - 1 FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 8,1967 PAGE TWENTY Manrt;f0t^r Eupning A v «h «B D bRy N et PkiMB R oi The Weather Vor Ute W«Us M m M MoaUy cloudy tonlgWt wtih ’The W om an'* ^AuxUtefy of Autpm 26, 1967 dianco cf abowera. Low 60 to tile' MlancheaitcT Midget and Night School liegistration About Town 66. C to u ^ tomorrow mocnfaiff. Pony Football AModatlpn will efiaexiag in alltemoon. High isi Manchester Veterans Council havo tte flrsit meeting o f the Sept. 19-20 at Tech School 14,590 70*. will meet Monday at 8 p.m. at season Monday at 8:30 p m . at POHED ROSE Manche$ter— A City of VUlage Charm the home of Mrs. James Ray SALE the American Legion Home. ''at least two years of exper- of 180 Ferguson Rd. The meet Registration for adult eve- (Okuwlfled AdvertifibiK on Fnf« 9) PRICE SEVEN CENTS fience in machine work. MANCHESTER, CONN., SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 9,* 1967 ing lis open to all interested ■'itlng courses at Howell' Cheney VOL. LXXXVI, NO. 289 (TWELVE PAGES—TV SECTION) Manchester Ckirden Club will Shop math is offered to Uiose women. REG. $2.50 have a member's horticultural Technical School will be held who wish to learn baste al dhq>lay Monday, at 8 p.m. at Sept 19 and 20 from 7 to 9 p.m. gebra, trigonometry, ■with a Center CongcegatlohUl ^u rcb. Orange Hall bingo will open 1.50 at the school office. brief review of the fundamen for Uie season tomorrow at 7:30 Mrs. -

Deconstructing Feminine and Feminist Fantastic Through the Study of Living Dolls

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 22 (2020) Issue 4 Article 7 Deconstructing Feminine and Feminist Fantastic through the Study of Living Dolls Raquel Velázquez University of Barcelona Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Spanish Literature Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Velázquez, Raquel. "Deconstructing Feminine and Feminist Fantastic through the Study of Living Dolls." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 22.4 (2020): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.3720> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. -

Congratulations Susan & Joost Ueffing!

CONGRATULATIONS SUSAN & JOOST UEFFING! The Staff of the CQ would like to congratulate Jaguar CO Susan and STARFLEET Chief of Operations Joost Ueffi ng on their September wedding! 1 2 5 The beautiful ceremony was performed OCT/NOV in Kingsport, Tennessee on September 2004 18th, with many of the couple’s “extended Fleet family” in attendance! Left: The smiling faces of all the STARFLEET members celebrating the Fugate-Ueffi ng wedding. Photo submitted by Wade Olsen. Additional photos on back cover. R4 SUMMIT LIVES IT UP IN LAS VEGAS! Right: Saturday evening banquet highlight — commissioning the USS Gallant NCC 4890. (l-r): Jerry Tien (Chief, STARFLEET Shuttle Ops), Ed Nowlin (R4 RC), Chrissy Killian (Vice Chief, Fleet Ops), Larry Barnes (Gallant CO) and Joe Martin (Gallant XO). Photo submitted by Wendy Fillmore. - Story on p. 3 WHAT IS THE “RODDENBERRY EFFECT”? “Gene Roddenberry’s dream affects different people in different ways, and inspires different thoughts... that’s the Roddenberry Effect, and Eugene Roddenberry, Jr., Gene’s son and co-founder of Roddenberry Productions, wants to capture his father’s spirit — and how it has touched fans around the world — in a book of photographs.” - For more info, read Mark H. Anbinder’s VCS report on p. 7 USPS 017-671 125 125 Table Of Contents............................2 STARFLEET Communiqué After Action Report: R4 Conference..3 Volume I, No. 125 Spies By Night: a SF Novel.............4 A Letter to the Fleet........................4 Published by: Borg Assimilator Media Day..............5 STARFLEET, The International Mystic Realms Fantasy Festival.......6 Star Trek Fan Association, Inc. -

Steam Engine Time 5

Steam Engine T ime PRIEST’S ‘THE SEPARATION’ MEMOS FROM NORSTRILIA CENSORSHIP IN AUSTRALIA POLITICS AND SF Harry Hennessey Buerkett James Doig Paul Kincaid Gillian Polack Eric S. Raymond Milan Smiljkovic Janine Stinson Issue 5 September 2006 Steam Engine T ime 5 STEAM ENGINE TIME No. 5, September 2006 is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia ([email protected]) and Janine Stinson, PO Box 248, Eastlake, MI 49626-0248, USA ([email protected]). Members fwa. First edition is in .PDF file format from eFanzines.com or from either of our email addresses. Print edition available for The Usual (letters or substantial emails of comment, artistic contributions, articles, reviews, traded publications or review copies) or subscriptions (Australia: $40 for 5, cheques to ‘Gillespie & Cochrane Pty Ltd’; Overseas: $US30 or £15 for 5, or equivalent, airmail; please send folding money, not cheques). Printed by Copy Place, 415 Bourke Street, Melbourne VIC 3000. The print edition is made possible by a generous financial donation. Graphics Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) (front cover). Photographs Covers of various books and magazines discussed in this issue; plus photos of (p. 5) Christopher Priest, by Ian Maule; (p. 24) Roger Dard, supplied by Kim Huett; (p. 25) Roger Dard fanzine contributions, supplied by Kim Huett; (p. 32) Nigel Burwood, Martin Stone and Bill Blackbeard, by John Baxter; (p. 39) David Boutland. 3 EDITORIAL 1: 32 Letters of comment ‘Dream your dreams’: A meditation on Babylon 5 John Baxter Janine Stinson Rosaleen Love Steve Jeffery 4 EDITORIAL 2 E. B. Frohvet Bruce Gillespie Steve Sneyd Sydney J. -

DVD Spring 2020 Catalog This Catalog Lists Only the Newest Acquired DVD Titles from Spring 2020

Braille and Talking Book Library P.O. Box 942837 Sacramento, CA 94237-0001 (800) 952-5666 (916) 654-1119 FAX Descriptive Video Service (DVS) DVD Spring 2020 Catalog This catalog lists only the newest acquired DVD titles from Spring 2020. This is not a complete listing of all DVD titles available. Included at the end of this catalog is a mail order form that lists these DVD titles alphabetically. You may also order DVDs by phone, fax, email, or in person. Each video in this catalog is assigned an identifying number that begins with “DVD”. For example, DVD 0525 is a DVD entitled “The Lion King”. You need a television with a DVD player or a computer with a DVD player to watch descriptive videos on DVD. When you insert a DVD into your player, you may have to locate the DVS track, usually found under Languages or Set-up Menus. Assistance from a sighted friend or family member may be helpful. Some patrons have found that for some DVDs, once the film has begun playing, pressing the "Audio" button repeatedly on their DVD player's remote control will help select the DVS track. MPAA Ratings are guidelines for suitability for certain audiences. G All ages PG Some material may not be suitable for children PG-13 Some material may be inappropriate for children under 13 R Under 17 requires accompanying adult guardian Film not suitable for MPAA rating (TV show, etc.) Some Not Rated material may not be suitable for children. Pre-Ratings Film made before MPAA ratings. Some material may not be suitable for children. -

Dolemite Is My Name

DOLEMITE IS MY NAME Written by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski FINAL IN THE BLACK We hear Marvin Gaye's "What's Goin' On" playing softly. VOICE I ain't lying. People love me. INT. DOLPHIN'S - DAY CU of a beat-up record from the 1950s. On the paper cover is a VERY YOUNG Rudy, in a tuxedo. It says "Rudy Moore - BUGGY RIDE" RUDY You play this, folks gonna start hoppin' and squirmin', just like back in the day. A hand lifts the record up to the face of RUDY RAY MOORE, late '40s, black, sweet, determined. RUDY When I sang this on stage, I swear to God, people fainted! Ambulance man was picking them off the floor! When I had a gig, the promoter would warn the hospital: "Rudy's on tonight -- you're gonna be carrying bodies out of the motherfucking club!" We see that we are in a RADIO BOOTH. A sign blinks "On The Air." The DJ, ROJ, frowns at the record. ROJ "Buggy Ride"? RUDY Wasn't no small-time shit. ROJ GodDAMN, Rudy! That record's 1000 years old! I've got Marvin Gaye singin' "Let's Get It On"! I can't be playin' no "Buggy Ride." (beat) Look, I have 60 seconds. I have to cue the next tune. Hm! Rudy bites his lip and walks away. Roj tries to go back to his job. He reaches for a Sly Stone single -- when Rudy suddenly bounds back up. RUDY How about "Step It Up and Go"? That's a real catchy rhythm-and-blues number. -

CAST BIOGRAPHIES Season 2 RICKY WHITTLE

CAST BIOGRAPHIES Season 2 RICKY WHITTLE (SHADOW MOON) Ricky Whittle was born in Oldham, near Manchester in the north of England. Growing up, Whittle excelled in various sports representing his country at youth level in football, rugby, American football and athletics. After being scouted by both Arsenal and Celtic Football Clubs, injuries forced him to pursue a law degree at Southampton University. It was here he began modeling, becoming the face of a Reebok campaign in 2000. Whittle left university to pursue an acting career and soon joined several action-packed seasons as bad boy Ryan Naysmith in Sky One’s “Dream Team.” Following that, Whittle quickly joined the U.K.’s hugely popular long-running drama, “Hollyoaks,” in which he played rookie cop Calvin Valentine to acclaim across 400+ episodes. In 2010, Whittle made the decision to relocate to California and, within months of settling in, booked the role of Captain George East in the romantic-comedy feature Austenland for Sony Pictures, which was produced by Twilight creator Stephanie Meyer. Additionally, he was soon cast in a major recurring role in VH1’s popular series, “Single Ladies.” Another major recurring role followed on The CW’s popular post-apocalyptic sci-fi series “The 100.” Whittle’s character, Lincoln, immediately became a fan-favorite character, so he was upped to a series regular. Simultaneously, Whittle also had a recurring arc as Daniel Zamora in ABC’s “Mistresses.” In 2016, after a vigorous casting process, Whittle won the coveted role of Shadow Moon in Starz’s “American Gods.” In 2017, Whittle was seen opposite Sanaa Lathan in the Netflix feature film Nappily Ever After, which is based on the novel of the same name by Trisha R. -

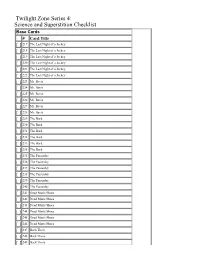

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 217 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 218 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 219 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 220 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 221 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 222 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 223 Mr. Bevis [ ] 224 Mr. Bevis [ ] 225 Mr. Bevis [ ] 226 Mr. Bevis [ ] 227 Mr. Bevis [ ] 228 Mr. Bevis [ ] 229 The Bard [ ] 230 The Bard [ ] 231 The Bard [ ] 232 The Bard [ ] 233 The Bard [ ] 234 The Bard [ ] 235 The Passersby [ ] 236 The Passersby [ ] 237 The Passersby [ ] 238 The Passersby [ ] 239 The Passersby [ ] 240 The Passersby [ ] 241 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 242 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 243 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 244 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 245 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 246 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 247 Back There [ ] 248 Back There [ ] 249 Back There [ ] 250 Back There [ ] 251 Back There [ ] 252 Back There [ ] 253 The Purple Testament [ ] 254 The Purple Testament [ ] 255 The Purple Testament [ ] 256 The Purple Testament [ ] 257 The Purple Testament [ ] 258 The Purple Testament [ ] 259 A Piano in the House [ ] 260 A Piano in the House [ ] 261 A Piano in the House [ ] 262 A Piano in the House [ ] 263 A Piano in the House [ ] 264 A Piano in the House [ ] 265 Night Call [ ] 266 Night Call [ ] 267 Night Call [ ] 268 Night Call [ ] 269 Night Call [ ] 270 Night Call [ ] 271 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 272 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 273 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 274 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 275 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 276 A Hundred