Mesopotamia 2550 B.C.: the Earliest Boundary Water Treaty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF Version of Article

STUDIA ORIENTALIA PUBLISHED BY THE FINNISH ORIENTAL SOCIETY 106 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS, AND SCHOLARS Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Edited by Mikko Luukko, Saana Svärd and Raija Mattila HELSINKI 2009 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS AND SCHOLARS clay or on a writing board and the other probably in Aramaic onleather in andtheotherprobably clay oronawritingboard ME FRONTISPIECE 118882. Assyrian officialandtwoscribes;oneiswritingincuneiformo . n COURTESY TRUSTEES OF T H E BRITIS H MUSEUM STUDIA ORIENTALIA PUBLISHED BY THE FINNISH ORIENTAL SOCIETY Vol. 106 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS, AND SCHOLARS Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Edited by Mikko Luukko, Saana Svärd and Raija Mattila Helsinki 2009 Of God(s), Trees, Kings, and Scholars: Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Studia Orientalia, Vol. 106. 2009. Copyright © 2009 by the Finnish Oriental Society, Societas Orientalis Fennica, c/o Institute for Asian and African Studies P.O.Box 59 (Unioninkatu 38 B) FIN-00014 University of Helsinki F i n l a n d Editorial Board Lotta Aunio (African Studies) Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila (Arabic and Islamic Studies) Tapani Harviainen (Semitic Studies) Arvi Hurskainen (African Studies) Juha Janhunen (Altaic and East Asian Studies) Hannu Juusola (Semitic Studies) Klaus Karttunen (South Asian Studies) Kaj Öhrnberg (Librarian of the Society) Heikki Palva (Arabic Linguistics) Asko Parpola (South Asian Studies) Simo Parpola (Assyriology) Rein Raud (Japanese Studies) Saana Svärd (Secretary of the Society) -

Republic of Iraq

Republic of Iraq Babylon Nomination Dossier for Inscription of the Property on the World Heritage List January 2018 stnel oC fobalbaT Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 State Party .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Province ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Name of property ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographical coordinates to the nearest second ................................................................................................. 1 Center ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 N 32° 32’ 31.09”, E 44° 25’ 15.00” ..................................................................................................................... 1 Textural description of the boundary .................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria under which the property is nominated .................................................................................................. 4 Draft statement -

Nabu 2015-2-Mep-Dc

ISSN 0989-5671 2015 N°2 (juin) NOTES BRÈVES 25) À propos d’ARET XII 344, des déesses dgú-ša-ra-tum et de la naissance du prince éblaïte* — Le texte administratif ARET XII 344 est malheureusement assez lacuneux, mais à notre avis quand même très intéressant. Les lignes du texte préservées sont les suivantes: r. I’:1’-5’: ‹x›[...] / šeš-[...] / in ⸢u₄⸣ / ḫúl / ⸢íl⸣-['à*-ag*-da*-mu*] v. II’:1’-11’: ...] K[ALAM.]KAL[AM(?)] / NI-šè-na-⸢a⸣ / ma-lik-tum / è / é / daš-dar / ap / íl-'à- ag-da-mu / i[n] / [...] / [...] r. III’:1’-9’: ⸢'à⸣-[...] / 1 gír mar-t[u] zú-aka / 1 buru₄-mušen 1 kù-sal / daš-dar / NAM-ra-luki / 1 zara₆-túg ú-ḫáb / 1 giš-šilig₅* 2 kù-sig₁₇ maš-maš-SÙ / 1 šíta zabar / dga-mi-iš r. IV’:1’-10’: ⸢x⸣[...] / 10 lá-3 an-dù[l] igi-DUB-SÙ šu-SÙ DU-SÙ kù:babbar / 10 lá-3 gú-a-tum zabar / dgú-ša-ra-tum / 5 kù-sig₁₇ / é / en / ni-zi-mu / 2 ma-na 55 kù-sig₁₇ / sikil r. V’:1’-6’: [x-]NE-[t]um / [x K]A-dù-gíd / [m]a-lik-tum / i[n-na-s]um / dga-mi-iš / 1 dib 2 giš- DU 2 ti-gi-na 2 geštu-lá 2 ba-ga-NE-su!(ZU) r. VI’:1’-6’: [...]⸢x⸣ / [m]a-[li]k-tum / [šu-ba₄-]ti / [x ki]n siki / [x-]li / [x-b]a-LUM. Tout d’abord, on remarquera qu’au début du texte on peut lire in ⸢u₄⸣ / ḫúl / ⸢íl⸣-['à*-ag*-da*- mu*], c’est-à-dire « dans le jour de la fête (en l’honneur) d’íl-'à-ag-da-mu ». -

The Limits of Middle Babylonian Archives1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenstarTs The Limits of Middle Babylonian Archives1 susanne paulus Middle Babylonian Archives Archives and archival records are one of the most important sources for the un- derstanding of the Babylonian culture.2 The definition of “archive” used for this article is the one proposed by Pedersén: «The term “archive” here, as in some other studies, refers to a collection of texts, each text documenting a message or a statement, for example, letters, legal, economic, and administrative documents. In an archive there is usually just one copy of each text, although occasionally a few copies may exist.»3 The aim of this article is to provide an overview of the archives of the Middle Babylonian Period (ca. 1500-1000 BC),4 which are often 1 All kudurrus are quoted according to Paulus 2012a. For a quick reference on the texts see the list of kudurrus in table 1. 2 For an introduction into Babylonian archives see Veenhof 1986b; for an overview of differ- ent archives of different periods see Veenhof 1986a and Brosius 2003a. 3 Pedersén 1998; problems connected to this definition are shown by Brosius 2003b, 4-13. 4 This includes the time of the Kassite dynasty (ca. 1499-1150) and the following Isin-II-pe- riod (ca. 1157-1026). All following dates are BC, the chronology follows – willingly ignoring all linked problems – Gasche et. al. 1998. the limits of middle babylonian archives 87 left out in general studies,5 highlighting changes in respect to the preceding Old Babylonian period and problems linked with the material. -

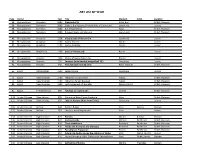

Art List by Year

ART LIST BY YEAR Page Period Year Title Medium Artist Location 36 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Standard of Ur Inlaid Box British Museum 36 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Stele of the Vultures (Victory Stele of Eannatum) Limestone Louvre 38 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Bull Headed Harp Harp British Museum 39 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Banquet Scene cylinder seal Lapis Lazoli British Museum 40 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2254 Victory Stele of Narum-Sin Sandstone Louvre 42 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2100 Gudea Seated Diorite Louvre 43 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2100 Gudea Standing Calcite Louvre 44 Mesopotamia Babylonian 1780 Stele of Hammurabi Basalt Louvre 45 Mesopotamia Assyrian 1350 Statue of Queen Napir-Asu Bronze Louvre 46 Mesopotamia Assyrian 750 Lamassu (man headed winged bull 13') Limestone Louvre 48 Mesopotamia Assyrian 640 Ashurbanipal hunting lions Relief Gypsum British Museum 65 Egypt Old Kingdom 2500 Seated Scribe Limestone Louvre 75 Egypt New Kingdom 1400 Nebamun hunting fowl Fresco British Museum 75 Egypt New Kingdom 1400 Nebamun funery banquet Fresco British Museum 80 Egypt New Kingdom 1300 Last Judgement of Hunefer Papyrus Scroll British Museum 81 Egypt First Millenium 680 Taharqo as a sphinx (2') Granite British Museum 110 Ancient Greece Orientalizing 625 Corinthian Black Figure Amphora Vase British Museum 111 Ancient Greece Orientalizing 625 Lady of Auxerre (Kore from Crete) Limestone Louvre 121 Ancient Greece Archaic 540 Achilles & Ajax Vase Execias Vatican 122 Ancient Greece Archaic 510 Herakles wrestling Antaios Vase Louvre 133 Ancient Greece High -

Some Remarks on the Origin of Ideology of Divine Warfare in Early Dynastic Lagaš

ISSN 2518-1521 (Online), ISSN 2226-2830 (Print) ВІСНИК МАРІУПОЛЬСЬКОГО ДЕРЖАВНОГО УНІВЕРСИТЕТУ СЕРІЯ: ІСТОРІЯ. ПОЛІТОЛОГІЯ, 2017, ВИП. 18 The historiographic review of M. Hrushevsky’s sociological researches emphasized the many-sided nature of the prominent historian’s scientific heritage. Especially it concerns the representatives of the emigrant and contemporary Ukrainian historical science. The historians of diaspora (L.Vynar, S. Zabrovarny, O. Pritsak) proved that the sociological-comparative method used by M. Hrushevsky in the historical research as social, economic and cultural synthesis of the nation’s history enhanced the capabilities to study it more systematically. It was stated that the outstanding scientist popularized the social history of Ukraine in the West-European scientific community with the help of his public lectures on historic and sociological topics. The contemporary Ukrainian historians (V. Bilodid, O. Kopylenko, V. Telvak, L. Chugaevska, I. Shostak, O. Yas and others) analysed the historian’s sociological works and stated world outlook evolution of Mykhailo Hrushevsky from the romantic narodnik movement to the critical rethinking of sociology. The analysis of M. Hrushevsky’s sociological heritage defined the interrelation of “public and national” and the state system as well as the main issues of sociology as a science and sociological ideas in Ukrainian national studies. The contemporary historians traced rethinking the historian’s research strategies. Key words: sociological works, emigrant period, historiographic analysis, Ukrainian historians, historians of diaspora, contemporary scientists. УДК 355.48(358) V. Sazonov SOME REMARKS ON THE ORIGIN OF IDEOLOGY OF DIVINE WARFARE IN EARLY DYNASTIC LAGAŠ Current article discusses the problem of origin of ideology of divine warfare and theology of war of Ancient Mesopotamian rulers in the Early Dynastic Lagaš (26-24th centuries BCE). -

After the Battle Is Over: the Stele of the Vultures and the Beginning Of

To raise the ofthe natureof narrative is to invite After the Battle Is Over: The Stele question reflectionon the verynature of culture. Hayden White, "The Value of Narrativity . ," 1981 of the Vultures and the Beginning of Historical Narrative in the Art Definitions of narrative, generallyfalling within the purviewof literarycriticism, are nonethelessimportant to of the Ancient Near East arthistorians. From the simpleststarting point, "for writing to be narrative,no moreand no less thana tellerand a tale are required.'1 Narrativeis, in otherwords, a solutionto " 2 the problemof "how to translateknowing into telling. In general,narrative may be said to make use ofthird-person cases and of past tenses, such that the teller of the story standssomehow outside and separatefrom the action.3But IRENE J. WINTER what is importantis thatnarrative cannot be equated with thestory alone; it is content(story) structured by the telling, University of Pennsylvania forthe organization of the story is whatturns it into narrative.4 Such a definitionwould seem to providefertile ground forart-historical inquiry; for what, after all, is a paintingor relief,if not contentordered by the telling(composition)? Yet, not all figuraiworks "tell" a story.Sometimes they "refer"to a story;and sometimesthey embody an abstract concept withoutthe necessaryaction and settingof a tale at all. For an investigationof visual representation, it seems importantto distinguishbetween instancesin which the narrativeis vested in a verbal text- the images servingas but illustrationsof the text,not necessarily"narrative" in themselves,but ratherreferences to the narrative- and instancesin whichthe narrativeis located in the represen- tations,the storyreadable throughthe images. In the specificcase of the ancientNear East, instances in whichnarrative is carriedthrough the imageryitself are rare,reflecting a situationfundamentally different from that foundsubsequently in the West, and oftenfrom that found in the furtherEast as well. -

The Calendars of Ebla. Part III. Conclusion

Andrews Unir~ersitySeminary Studies, Summer 1981, Vol. 19, No. 2, 115-126 Copyright 1981 by Andrews University Press. THE CALENDARS OF EBLA PART 111: CONCLUSION WILLIAM H. SHEA Andrews University In my two preceding studies of the Old and New Calendars of Ebla (see AUSS 18 [1980]: 127-137, and 19 [1981]: 59-69), interpreta- tions for the meanings of 22 out of 24 of their month names have been suggested. From these studies, it is evident that the month names of the two calendars can be analyzed quite readily from the standpoint of comparative Semitic linguistics. In other words, the calendars are truly Semitic, not Sumerian. Sumerian logograms were used for the names of two months of the Old Calendar and three months of the New Calendar, but it is most likely that the scribes at Ebla read these logograms with a Semitic equivalent. In the cases of the three logograms in the New Calendar these equiva- lents are reasonably clear, but the meanings of the names of the seventh and eighth months in the Old Calendar remain obscure. Not only do these month names lend themselves to a ready analysis on the basis of comparative Semitic linguistics, but, as we have also seen, almost all of them can be analyzed satisfactorily just by comparing them with the vocabulary of biblical Hebrew. Given some simple and well-known phonetic shifts, Hebrew cognates can be suggested for some 20 out of 24 of the month names in these two calendars. Some of the etymologies I have suggested may, of course, be wrong; but even so, the rather full spectrum of Hebrew cognates available for comparison probably would not be diminished greatly. -

A Comparison of the Role of Bārû and Mantis in Ancient Warfare

A Comparison of the Role of Bārû and Mantis in Ancient Warfare Krzysztof Ulanowski Divination played a huge role in both the Mesopotamian and Greek civiliza- tions. Diviners were consulted by their clients in all possible situations. The results of divination were especially important during times of war, when asso- ciated with the very life of the king along with thousands of others. Divination was a salient characteristic of Mesopotamian civilization; likewise, in Greek politics and warfare, a leader who ignored omens would incur the ominous anger impressions of those by whom he was followed.1 In this paper I will compare the role and responsibility of diviners in two different civilizations in relation to the affairs of war. What did the Assyrian bārû and the Greek mantis (μάντις) have in common and in what ways did they differ? Could they really decide the course of battles? Would it be possible to describe the skills of the bārû priest in the words of Euripides: “the best mantis is he who guesses well”?2 War When writing systems first appeared in the history of both Mesopotamian and Greek civilizations, the first written works not only had a codifying- mythological nature, but above all a military character. Weil’s essay, L’Iliade ou le poème de la force holds that “the true hero, the true subject at the centre of the Iliad is force”.3 Homer was the poet of war and the Iliad needs hardly be mentioned. In the case of Mesopotamian civilization, one could refer not only to The Gilgamesh Epic, but also to many other Sumerian, and therefore early texts which have war as a leading motif, such as The Victory of Eanatum 1 M.A. -

What Is Digital Signal Processing?

Chapter 1 What Is Digital Signal Processing? A signal, technically yet generally speaking, is a a formal description of a phenomenon evolving over time or space; by signal processing we denote any manual or “mechanical” operation which modifies, analyzes or other- wise manipulates the information contained in a signal. Consider the sim- ple example of ambient temperature: once we have agreed upon a formal model for this physical variable – Celsius degrees, for instance – we can record the evolution of temperature over time in a variety of ways and the resulting data set represents a temperature “signal”. Simple processing op- erations can then be carried out even just by hand: for example, we can plot thesignalongraphpaperasinFigure1.1,orwecancomputederivedpa- rameters such as the average temperature in a month. Conceptually, it is important to note that signal processing operates on an abstract representation of a physical quantity and not on the quantity it- self. At the same time, the type of abstract representation we choose for the physical phenomenon of interest determines the nature of a signal process- ing unit. A temperature regulation device, for instance, is not a signal pro- cessing system as a whole. The device does however contain a signal pro- cessing core in the feedback control unit which converts the instantaneous measure of the temperature into an ON/OFF trigger for the heating element. The physical nature of this unit depends on the temperature model: a sim- ple design is that of a mechanical device based on the dilation of a metal sensor; more likely, the temperature signal is a voltage generated by a ther- mocouple and in this case the matched signal processing unit is an opera- tional amplifier. -

Forgetting the Sumerians in Ancient Iraq Jerrold Cooper Johns Hopkins University

“I have forgotten my burden of former days!” Forgetting the Sumerians in Ancient Iraq Jerrold Cooper Johns Hopkins University The honor and occasion of an American Oriental Society presidential address cannot but evoke memories. The annual AOS meeting is, after all, the site of many of our earliest schol- arly memories, and more recent ones as well. The memory of my immediate predecessor’s address, a very hard act to follow indeed, remains vivid. Sid Griffiths gave a lucid account of a controversial topic with appeal to a broad audience. His delivery was beautifully attuned to the occasion, and his talk was perfectly timed. At the very first AOS presidential address I attended, the speaker was a bit tipsy, and, ten minutes into his talk, he looked at his watch and said, “Oh, I’ve gone on too long!” and sat down. I also remember a quite different presi- dential address in which, after an hour had passed, the speaker declared, “I know I’ve been talking for a long time, but since this is the first and only time most of you will hear anything about my field, I’ll continue on until you’ve heard all I think you ought to know!” It is but a small move from individual memory to cultural memory, a move I would like to make with a slight twist. As my title announces, the subject of this communication will not be how the ancient Mesopotamians remembered their past, but rather how they managed to forget, or seemed to forget, an important component of their early history. -

DESENVOLVIMENTO DO ESQUEMA DECORATIVO DAS SALAS DO TRONO DO PERÍODO NEO-ASSÍRIO (934-609 A.C.): IMAGEM TEXTO E ESPAÇO COMO VE

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO MUSEU DE ARQUEOLOGIA E ETNOLOGIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ARQUEOLOGIA DESENVOLVIMENTO DO ESQUEMA DECORATIVO DAS SALAS DO TRONO DO PERÍODO NEO-ASSÍRIO (934-609 a.C.): IMAGEM TEXTO E ESPAÇO COMO VEÍCULOS DA RETÓRICA REAL VOLUME I PHILIPPE RACY TAKLA Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Arqueologia do Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia da Universidade de São Paulo para obtenção do título de Mestre em Arqueologia. Orientadora: Profª. Drª. ELAINE FARIAS VELOSO HIRATA Linha de Pesquisa: REPRESENTAÇÕES SIMBÓLICAS EM ARQUEOLOGIA São Paulo 2008 RESUMO Este trabalho busca a elaboração de um quadro interpretativo que possibilite analisar o desenvolvimento do esquema decorativo presente nas salas do trono dos palácios construídos pelos reis assírios durante o período que veio a ser conhecido como neo- assírio (934 – 609 a.C.). Entendemos como esquema decorativo a presença de imagens e textos inseridos em um contexto arquitetural. Temos por objetivo demonstrar que a evolução do esquema decorativo, dada sua importância como veículo da retórica real, reflete a transformação da política e da ideologia imperial, bem como das fronteiras do império, ao longo do período neo-assírio. Palavras-chave: Assíria, Palácio, Iconografia, Arqueologia, Ideologia. 2 ABSTRACT The aim of this work is the elaboration of a interpretative framework that allow us to analyze the development of the decorative scheme of the throne rooms located at the palaces built by the Assyrians kings during the period that become known as Neo- Assyrian (934 – 609 BC). We consider decorative scheme as being the presence of texts and images in an architectural setting.