An AZ Companion to Ancient Egyptian Architecture Free

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Evaluation of Two Recent Theories Concerning the Narmer Palette1

Eras Edition 8, November 2006 – http://www.arts.monash.edu.au/eras An Evaluation of Two Recent Theories Concerning the Narmer Palette1 Benjamin P. Suelzle (Monash University) Abstract: The Narmer Palette is one of the most significant and controversial of the decorated artefacts that have been recovered from the Egyptian Protodynastic period. This article evaluates the arguments of Alan R. Schulman and Jan Assmann, when these arguments dwell on the possible historicity of the palette’s decorative features. These two arguments shall be placed in a theoretical continuum. This continuum ranges from an almost total acceptance of the historical reality of the scenes depicted upon the Narmer Palette to an almost total rejection of an historical event or events that took place at the end of the Naqada IIIC1 period (3100-3000 BCE) and which could have formed the basis for the creation of the same scenes. I have adopted this methodological approach in order to establish whether the arguments of Assmann and Schulman have any theoretical similarities that can be used to locate more accurately the palette in its appropriate historical and ideological context. Five other decorated stone artefacts from the Protodynastic period will also be examined in order to provide historical comparisons between iconography from slightly earlier periods of Egyptian history and the scenes of royal violence found upon the Narmer Palette. Introduction and Methodology Artefacts of iconographical importance rarely survive intact into the present day. The Narmer Palette offers an illuminating opportunity to understand some of the ideological themes present during the political unification of Egypt at the end of the fourth millennium BCE. -

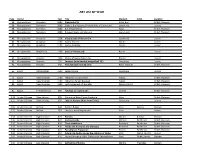

Art List by Year

ART LIST BY YEAR Page Period Year Title Medium Artist Location 36 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Standard of Ur Inlaid Box British Museum 36 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Stele of the Vultures (Victory Stele of Eannatum) Limestone Louvre 38 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Bull Headed Harp Harp British Museum 39 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Banquet Scene cylinder seal Lapis Lazoli British Museum 40 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2254 Victory Stele of Narum-Sin Sandstone Louvre 42 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2100 Gudea Seated Diorite Louvre 43 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2100 Gudea Standing Calcite Louvre 44 Mesopotamia Babylonian 1780 Stele of Hammurabi Basalt Louvre 45 Mesopotamia Assyrian 1350 Statue of Queen Napir-Asu Bronze Louvre 46 Mesopotamia Assyrian 750 Lamassu (man headed winged bull 13') Limestone Louvre 48 Mesopotamia Assyrian 640 Ashurbanipal hunting lions Relief Gypsum British Museum 65 Egypt Old Kingdom 2500 Seated Scribe Limestone Louvre 75 Egypt New Kingdom 1400 Nebamun hunting fowl Fresco British Museum 75 Egypt New Kingdom 1400 Nebamun funery banquet Fresco British Museum 80 Egypt New Kingdom 1300 Last Judgement of Hunefer Papyrus Scroll British Museum 81 Egypt First Millenium 680 Taharqo as a sphinx (2') Granite British Museum 110 Ancient Greece Orientalizing 625 Corinthian Black Figure Amphora Vase British Museum 111 Ancient Greece Orientalizing 625 Lady of Auxerre (Kore from Crete) Limestone Louvre 121 Ancient Greece Archaic 540 Achilles & Ajax Vase Execias Vatican 122 Ancient Greece Archaic 510 Herakles wrestling Antaios Vase Louvre 133 Ancient Greece High -

After the Battle Is Over: the Stele of the Vultures and the Beginning Of

To raise the ofthe natureof narrative is to invite After the Battle Is Over: The Stele question reflectionon the verynature of culture. Hayden White, "The Value of Narrativity . ," 1981 of the Vultures and the Beginning of Historical Narrative in the Art Definitions of narrative, generallyfalling within the purviewof literarycriticism, are nonethelessimportant to of the Ancient Near East arthistorians. From the simpleststarting point, "for writing to be narrative,no moreand no less thana tellerand a tale are required.'1 Narrativeis, in otherwords, a solutionto " 2 the problemof "how to translateknowing into telling. In general,narrative may be said to make use ofthird-person cases and of past tenses, such that the teller of the story standssomehow outside and separatefrom the action.3But IRENE J. WINTER what is importantis thatnarrative cannot be equated with thestory alone; it is content(story) structured by the telling, University of Pennsylvania forthe organization of the story is whatturns it into narrative.4 Such a definitionwould seem to providefertile ground forart-historical inquiry; for what, after all, is a paintingor relief,if not contentordered by the telling(composition)? Yet, not all figuraiworks "tell" a story.Sometimes they "refer"to a story;and sometimesthey embody an abstract concept withoutthe necessaryaction and settingof a tale at all. For an investigationof visual representation, it seems importantto distinguishbetween instancesin which the narrativeis vested in a verbal text- the images servingas but illustrationsof the text,not necessarily"narrative" in themselves,but ratherreferences to the narrative- and instancesin whichthe narrativeis located in the represen- tations,the storyreadable throughthe images. In the specificcase of the ancientNear East, instances in whichnarrative is carriedthrough the imageryitself are rare,reflecting a situationfundamentally different from that foundsubsequently in the West, and oftenfrom that found in the furtherEast as well. -

DESENVOLVIMENTO DO ESQUEMA DECORATIVO DAS SALAS DO TRONO DO PERÍODO NEO-ASSÍRIO (934-609 A.C.): IMAGEM TEXTO E ESPAÇO COMO VE

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO MUSEU DE ARQUEOLOGIA E ETNOLOGIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ARQUEOLOGIA DESENVOLVIMENTO DO ESQUEMA DECORATIVO DAS SALAS DO TRONO DO PERÍODO NEO-ASSÍRIO (934-609 a.C.): IMAGEM TEXTO E ESPAÇO COMO VEÍCULOS DA RETÓRICA REAL VOLUME I PHILIPPE RACY TAKLA Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Arqueologia do Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia da Universidade de São Paulo para obtenção do título de Mestre em Arqueologia. Orientadora: Profª. Drª. ELAINE FARIAS VELOSO HIRATA Linha de Pesquisa: REPRESENTAÇÕES SIMBÓLICAS EM ARQUEOLOGIA São Paulo 2008 RESUMO Este trabalho busca a elaboração de um quadro interpretativo que possibilite analisar o desenvolvimento do esquema decorativo presente nas salas do trono dos palácios construídos pelos reis assírios durante o período que veio a ser conhecido como neo- assírio (934 – 609 a.C.). Entendemos como esquema decorativo a presença de imagens e textos inseridos em um contexto arquitetural. Temos por objetivo demonstrar que a evolução do esquema decorativo, dada sua importância como veículo da retórica real, reflete a transformação da política e da ideologia imperial, bem como das fronteiras do império, ao longo do período neo-assírio. Palavras-chave: Assíria, Palácio, Iconografia, Arqueologia, Ideologia. 2 ABSTRACT The aim of this work is the elaboration of a interpretative framework that allow us to analyze the development of the decorative scheme of the throne rooms located at the palaces built by the Assyrians kings during the period that become known as Neo- Assyrian (934 – 609 BC). We consider decorative scheme as being the presence of texts and images in an architectural setting. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49596-7 — the Amorites and the Bronze Age Near East Aaron A

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49596-7 — The Amorites and the Bronze Age Near East Aaron A. Burke Index More Information INDEX ꜤꜢmw (Egyptian term), 145–47 See also Asiatics “communities of practice,” 18–20, 38–40, 42, (Egypt) 347–48 decline of, 350–51 A’ali, 226 during Early Bronze Age, 31 ‘Aa-zeh-Re’ Nehesy, 316–17 Ebla, 38–40, 56, 178 Abarsal, 45 emergence of, 23, 346–47 Abda-El (Amorite), 153–54 extensification of, 18–20 Abi-eshuh, 297, 334–35 hollow cities, 178–79 Abisare (Larsa), 160 Jazira, 38, 177 Abishemu I (Byblos), 175 “land rush,” 177–78 Abraham, 6 Mari, 38–40, 56, 177–79, 227–28 abu as symbolic kinship, 268–70 Nawar, 38, 40, 42 Abu en-Ni’aj, Tell, 65 Northern Levant, 177 Abu Hamad, 54 Qatna, 179 Abu Salabikh, 100 revival of, 176–80, 357 Abusch, Tzvi, 186 Shubat Enlil, 177–78, 180 Abydos, 220 social identity of Amorites and, 10 Achaemenid Empire, 12 Urkesh, 38, 42 Achsaph, 176 wool trade and, 23 ‘Adabal (deity), 40 Yamḫ ad, 179 Adad/Hadad (deity), 58–59, 134, 209–10, 228–29, zone of uncertainty and, 24, 174 264, 309–11, 338, 364 Ahbabu, 131 Adams, Robert, 128 Ahbutum (tribe), 97 Adamsah, 109 Ahktoy III, 147 Adba-El (Mari), 153–54 Ahmar, Tell, 51–53, 56, 136, 228 Addahushu (Elam), 320 Ahmose, 341–42 Ader, 50 ‘Ai, 33 Admonitions of Ipuwer, 172 ‘Ain Zurekiyeh, 237–38 aDNA. See DNA Ajjul, Tell el-, 142, 237–38, 326, 329, 341–42 Adnigkudu (deity), 254–55 Akkadian Empire. -

The Lagash-Umma Border Conflict 9

CHAPTER I Introduction: Early Civilization and Political Organization in Babylonia' The earliest large urban agglomoration in Mesopotamia was the city known as Uruk in later texts. There, around 3000 B.C., certain distinctive features of historic Mesopotamian civilization emerged: the cylinder seal, a system of writing that soon became cuneiform, a repertoire of religious symbolism, and various artistic and architectural motifs and conven- tions.' Another feature of Mesopotamian civilization in the early historic periods, the con- stellation of more or less independent city-states resistant to the establishment of a strong central political force, was probably characteristic of this proto-historic period as well. Uruk, by virtue of its size, must have played a dominant role in southern Babylonia, and the city of Kish probably played a similar role in the north. From the period that archaeologists call Early Dynastic I1 (ED 11), beginning about 2700 B.c.,~the appearance of walls around Babylonian cities suggests that inter-city warfare had become institutionalized. The earliest royal inscriptions, which date to this period, belong to kings of Kish, a northern Babylonian city, but were found in the Diyala region, at Nippur, at Adab and at Girsu. Those at Adab and Girsu are from the later part of ED I1 and are in the name of Mesalim, king of Kish, accompanied by the names of the respective local ruler^.^ The king of Kish thus exercised hegemony far beyond the walls of his own city, and the memory of this particular king survived in native historical traditions for centuries: the Lagash-Umma border was represented in the inscriptions from Lagash as having been determined by the god Enlil, but actually drawn by Mesalim, king of Kish (IV.1). -

Chapter 2 the Rise of Civilization: the Art of the Ancient Near East

Chapter 2 The Rise of Civilization: The Art of the Ancient Near East Multiple Choice Select the response that best answers the question or completes the statement. 1. The change in the nature of daily life, from hunter and gatherer to farmer and herder, first occurred in ______________. a. Mesopotamia c. Africa b. Europe d. Asia 2. Mesopotamia is known as the __________ ___________. a. River Crescent c. Fertile Crescent b. Delta Crescent d. Pearl Crescent 3. The ___________ ruled the northern Mesopotamian empire during the ninth through seventh centuries BCE. a. Sumerians c. Akkadians b. Assyrians d. Sasanians 4. What site did Leonard Woolley excavate in the 1920s in southern Mesopotamia? a. Royal Cemetery at Giza c. Royal Palace at Nineveh b. Ziggurat of Ur d. Royal Cemetery at Ur 5. The ___________ are credited with developing the first known writing system. a. Assyrians c. Sumerians b. Babylonians d. Elamites 6. The most famous Sumerian work of literature is the _____________________. a. Illiad c. Odyssey b. Tale of Gilgamesh d. Tale of Urnanshe 7. In Sumerian cities the ________ formed the nucleus of the city. a. temple c. palace b. market d. treasury 8. The temples of Sumer were placed on high platforms or ___________. a. pyramids c. daises b. ziggurats d. towers 9. What is the theme of the Stele of the Vultures? a. warfare c. trade b. prayer d. royal contract 7 10. The earliest known name of an author is _____________. a. Nanna c. Sargon b. Enheduanna d. Gudea 11. Hammurabi is most famous for his ____________. -

Images of Power

IMAGES OF POWER: PREDYNASTIC and OLD KINGDOM EGYPT: FOCUS (Egyptian Sculpture of Predynastic and Old Kingdom Egypt) ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: http://smarthisto ry.khanacademy .org/palette-of- king- narmer.html TITLE or DESIGNATION: Palette of Narmer CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Predynastic Egyptian DATE: c. 3100- 3000 B.C.E. MEDIUM: slate TITLE or DESIGNATION: Seated Statue of Khafre, from his mortuary temple at Gizeh CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Old Kingdom Egyptian DATE: c. 2575-2525 B.C.E. MEDIUM: diorite ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: https://www.khanacademy.org/human ities/ancient-art-civilizations/egypt- art/predynastic-old-kingdom/a/king- menkaure-mycerinus-and-queen TITLE or DESIGNATION: King Menkaure and his queen (possibly Khamerernebty) CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Old Kingdom Egyptian DATE: c. 2490-2472 B.C.E. MEDIUM: slate ONLINE ASSIGNMENT: https://www.khanacademy. org/humanities/ancient- art-civilizations/egypt- art/predynastic-old- kingdom/v/the-seated- scribe-c-2620-2500-b-c-e TITLE or DESIGNATION: Seated Scribe from Saqqara CULTURE or ART HISTORICAL PERIOD: Old Kingdom Egyptian DATE: c. 2450-2325 B.C.E. MEDIUM: painted limestone with inlaid eyes of rock crystal, calcite, and magnesite IMAGES OF POWER: PREDYNASTIC and OLD KINGDOM EGYPT: SELECTED TEXT (Egyptian Sculpture of Predynastic and Old Kingdom Egypt) The Palette of King Narmer, c. 3100-3000 BCE, slate Dating from about the 31st century BCE, this “palette” contains some of the earliest hieroglyphic inscriptions ever found. It is thought by some to depict the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the king Narmer. On one side, the king is depicted with the bulbous White crown of Upper (southern) Egypt, and the other side depicts the king wearing the level Red Crown of Lower (northern) Egypt. -

Download Download

JIIA.eu Journal of Intercultural and Interdisciplinary Archaeology The fantastic creatures in Predynastic Egypt: an essay about Near-Eastern influences Giulia Pizzato Interuniversity Archaeology Post-Graduate Specialization School (Udine, Trieste and Venice Universities). [email protected] This article investigates the presence of fantastic creatures in the Egyptian Predynastic records, their meaning and the Near-Eastern influences on the Egyptian iconography in this period. The Predynastic period (3900-2900 BC)1 is at the basis of Egyptian history, therefore its analysis plays a fundamental role in order to understand future developments of the Egyptian thought. The word “monster” derives from the Latin monstrum and according to our western culture tradition, it implies a moral component linked to the unknown and tending to identify awful entities. Therefore, it is more accurate to employ the German word Mischwesen2 because in ancient times monsters were also conceived as spirits, demons, gods. Firstly it is important to address the topic from an anthropological point of view: monsters are products of human minds and they have been existing since 30.000 years ago as chaos symbols, they are deformed creatures compared to reality, and it is impossible to include them in a taxonomy.3 A fantastic creature is a mixture of different parts of various animals forming a supernatural being, in which every part has its own value, and it is chosen for a particular reason. Every Mischwesen entails a study of the composition of its body, whose assembly work has to create a final harmonious figure; its meaning becomes part of the culture, this is the reason why a fantastic creature could be read and understand in different ages. -

BEADS of MYANMAR (BURMA) Line Decorated Beads Amongst the Pyu and Chin

INDIA \ { / CHINA .~ .~ ')• Qj' /J }. I ) --..-: iV·-· (/ ( \ :z:! r-' ......... :\ ~ \ . ~· ~ Q ' \ (1) < \ Ayadaw.~ / o...J "- rJ' (Monywai) \ .--.'l__ ~ ( • Kadaw • • Am arapura (Taungthaman ) • 00 Tanaung Daing • • Maingmaw '1...--../' /-~ Pagan • • Waddi •Pinle f" • Beinnaka -!:7 Pyawbwee •Nyaungyan ,/ LAOS Taungdwingyi • Yamethin \"·AJ'· • • • Tatkon .- ) Beikthano \......-. ) Shrikshetra • (Prome) • Chiang Mai • Thegon \ ( '.../ Kyaikka.tha "-. \ • Thaton ") • Hwawbi \) (Sa npa~ago) j ,,..> \ THAILAND \ •Thagara (Tavoy) \ J Andaman Sea \ \ "t / / ( 0 200 km I Figure 1. Ancient bead sites of Myanmar. BEADS OF MYANMAR (BURMA) Line Decorated Beads Amongst the Pyu and Chin ELIZABETH MOORE AND U AUNG MYINT ILLUSTRATIONS BY ROBERT MOORE AND U AUNG MYINT SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF LONDON Introduction The most common line decorated bead shape, whether ancient or modern, is spherical. Repetition of patterns on vari ous bead forms, however, suggests that designs were signifi The use of beads is common amongst many of the ethnic groups cantwhatever the shape. The Pyu sites ofMaingmaw(: ~~:Gen.) of Myanmar. Antique beads are valued for their inherent ances and Waddi (o ~: ), for example, are some sixty kilometres tral potency, and are used together with newer beads. This apart but possess almost identical sets of beads (see map 2). The combination of ancient and modern is particularly striking importance of pattern is also borne out by finds of black Pyu amongst the Chin peoples. Old beads favoured by the Chin beads with white lines made by three different techniques: originate from Pyu and Mon sites dated to the early first painting, incising, and an alkali resist. In the first technique, the millenniumA.D.1 Theseincludezoomorphicaswellasgeomet white lines are painted on the surface. -

Walking with the Unicorn Social Organization and Material Culture in Ancient South Asia

Walking with the Unicorn Social Organization and Material Culture in Ancient South Asia Jonathan Mark KenoyerAccess Felicitation Volume Open Edited by Dennys Frenez, Gregg M. Jamison, Randall W. Law, Massimo Vidale and Richard H. Meadow Archaeopress Archaeopress Archaeology © Archaeopress and the authors, 2017. Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978 1 78491 917 7 ISBN 978 1 78491 918 4 (e-Pdf) © ISMEO - Associazione Internazionale di Studi sul Mediterraneo e l'Oriente, Archaeopress and the authors 2018 Front cover: SEM microphotograph of Indus unicorn seal H95-2491 from Harappa (photograph by J. Mark Kenoyer © Harappa Archaeological Research Project). Access Back cover, background: Pot from the Cemetery H Culture levels of Harappa with a hoard of beads and decorative objects (photograph by Toshihiko Kakima © Prof. Hideo Kondo and NHK promotions). Back cover, box: Jonathan Mark Kenoyer excavating a unicorn seal found at Harappa (© Harappa Archaeological Research Project). Open ISMEO - Associazione Internazionale di Studi sul Mediterraneo e l'Oriente Corso Vittorio Emanuele II, 244 Palazzo Baleani Archaeopress Roma, RM 00186 www.ismeo.eu Serie Orientale Roma, 15 This volume was published with the financial assistance of a grant from the Progetto MIUR 'Studi e ricerche sulle culture dell’Asia e dell’Africa: tradizione e continuità, rivitalizzazione e divulgazione' All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by The Holywell Press, Oxford This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com © Archaeopress and the authors, 2017. -

The Gazelle in Ancient Egyptian Art Image and Meaning

Uppsala Studies in Egyptology - 6 - Department of Archaeology and Ancient History Uppsala University For my parents Dorrit and Hindrik Åsa Strandberg The Gazelle in Ancient Egyptian Art Image and Meaning Uppsala 2009 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in the Auditorium Minus of the Museum Gustavianum, Uppsala, Friday, October 2, 2009 at 09:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Strandberg, Åsa. 2009. The Gazelle in Ancient Egyptian Art. Image and Meaning. Uppsala Studies in Egyptology 6. 262 pages, 83 figures. Published by the Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University. xviii +262 pp. ISSN 1650-9838, ISBN 978-91-506-2091-7. This thesis establishes the basic images of the gazelle in ancient Egyptian art and their meaning. A chronological overview of the categories of material featuring gazelle images is presented as a background to an interpretation. An introduction and review of the characteristics of the gazelle in the wild are presented in Chapters 1-2. The images of gazelle in the Predynastic material are reviewed in Chapter 3, identifying the desert hunt as the main setting for gazelle imagery. Chapter 4 reviews the images of the gazelle in the desert hunt scenes from tombs and temples. The majority of the motifs characteristic for the gazelle are found in this context. Chapter 5 gives a typological analysis of the images of the gazelle from offering processions scenes. In this material the image of the nursing gazelle is given particular importance. Similar images are also found on objects, where symbolic connotations can be discerned (Chapter 6).