Heroides and Amores

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Microfilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)” . If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth)

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth) Uranus (Heaven) Oceanus = Tethys Iapetus (Titan) = Clymene Themis Atlas Menoetius Prometheus Epimetheus = Pandora Prometheus • “Prometheus made humans out of earth and water, and he also gave them fire…” (Apollodorus Library 1.7.1) • … “and scatter-brained Epimetheus from the first was a mischief to men who eat bread; for it was he who first took of Zeus the woman, the maiden whom he had formed” (Hesiod Theogony ca. 509) Prometheus and Zeus • Zeus concealed the secret of life • Trick of the meat and fat • Zeus concealed fire • Prometheus stole it and gave it to man • Freidrich H. Fuger, 1751 - 1818 • Zeus ordered the creation of Pandora • Zeus chained Prometheus to a mountain • The accounts here are many and confused Maxfield Parish Prometheus 1919 Prometheus Chained Dirck van Baburen 1594 - 1624 Prometheus Nicolas-Sébastien Adam 1705 - 1778 Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus • Novel by Mary Shelly • First published in 1818. • The first true Science Fiction novel • Victor Frankenstein is Prometheus • As with the story of Prometheus, the novel asks about cause and effect, and about responsibility. • Is man accountable for his creations? • Is God? • Are there moral, ethical constraints on man’s creative urges? Mary Shelly • “I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world” (Introduction to the 1831 edition) Did I request thee, from my clay To mould me man? Did I solicit thee From darkness to promote me? John Milton, Paradise Lost 10. -

Noé Sangariou: Étude Sur Le Déluge En Phrygie Et Le Syncrétisme Judéo-Phrygien, Paris : A

Adolphe Joseph Reinach Noé Sangariou: Étude sur le déluge en Phrygie et le syncrétisme judéo-phrygien, Paris : A. Durlacher, 1913, 95 p. Ce document fait partie des collections numériques des Archives Paul Perdrizet, le projet de recherche et de valorisation des archives scientifiques de ce savant conservées à l’Université de Lorraine. Il est diffusé sous la licence libre « Licence Ouverte / Open Licence ». http://perdrizet.hiscant.univ-lorraine.fr NOÉ SANGARIOTJ tTUDE SUR LE D~LUGE EN PHRYGIE ET LE SYNCRÉTISME JUDÉO·PHRYGIEN PAR Adolphe REINACH PARIS LIBRAIRIE A. DURLACHER 83 bis, RUE LAFAYETTE i9!3 NOÉ SANGARIOTJ tTUDE SUR LE D~LUGE EN PHRYGIE ET LE SYNCRÉTISME JUDÉO·PHRYGIEN PAR Adolphe REINACH PARIS LIBRAIRIE A. DURLACHER 83 bis, RUE LAFAYETTE i9!3 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 NOÉ SAN<;ARIOU ÉTUDE SUR LE DÉLUGE EN PHRYGIE ET LE SYNCHÉTISME JUDÉO-PHRYGIEN VERSAILLES. - IMP. CERF, !)9, RUE DUPLESSIS. NOÉ SANGARIOU ~TUDE SUR LE D~LUGE EN PHRYGIE ET LE SYNCRÉTISME JUD~O·PHRYGIEN PAR Adolphe REINACH PARIS LIBRAIRIE A. DURLACHER 83 bis, RUE LAFAYETTE 1913 NOÉ SANGARIOU ÉTUDE SOR LE DÉLUGE EN PHRYGIE ET LE SYNCRÉTISME JUDÉO-PHRYGIEN L'idée du présent mémoit·e est due à une découverte qui en explique le tit l'e. Le nom de Noé Sangariou, lu sur une épitaphe trouvée clans les fouilles de Tllasos, m'a aussitôt suggéré que, si l'on pouvait prouver que Noé fut un des noms portés par l'hypostase de la Grande Déesse J:?lu·ygienne connue généralement sons le nom de Nana, fille elu Sangarios, le fleuve de Cybèle, on pourrait clé duire de ce fait, pour la localisation à Apamée en Phrygie de l'Mche de Noé, une explication meilleure que celles qui ont été jus qu'ici proposées. -

Entre Ombre Et Lumière : Les Voix Féminines Dans Les Métamorphoses

Entre ombre et lumière : les voix féminines dans les Métamorphoses Hélène Vial Fondée sur l’articulation entre les passions des âmes et les métamorphoses des corps, l’esthétique des Métamorphoses d’Ovide délivre à la fois une vision audacieuse du monde et une conception neuve de l’entreprise poétique, le texte ovidien étant investi d’une très forte dimension réflexive due notamment à la correspondance exacte entre son sujet, la métamorphose, et sa forme, une écriture de la variation1. Or, la densité métalittéraire du poème est particulièrement grande dans les passages où se trouvent associés deux motifs qui constituent le sujet même du présent volume : celui de la voix et celui de la féminité. D’une part, la question de la voix est centrale dans les Métamorphoses ; d’autre part, les mythes féminins y sont très nombreux et d’une grande richesse symbolique ; et quand le poète relie l’une aux autres, la voix féminine apparaît dotée d’une capacité particulièrement saillante « à être inductric[e] de poésie », comme le disait l’appel à communication du séminaire qui a donné naissance à ce livre2, autrement dit à faire signe vers l’écriture et à parler du projet poétique dans son entier. C’est cette capacité qui constitue l’objet de mon analyse : dans la foule des silhouettes mythiques qui traversent les Métamorphoses et dont la voix nous est donnée à entendre, y a-t- il une spécificité féminine ? Et plus précisément, que nous disent sur la conception ovidienne de la poésie les paroles prononcées par ces figures féminines de l’ombre et du mystère3 -

Paleoseismology of the North Anatolian Fault at Güzelköy

Paleoseismology of the North Anatolian Fault at Güzelköy (Ganos segment, Turkey): Size and recurrence time of earthquake ruptures west of the Sea of Marmara Mustapha Meghraoui, M. Ersen Aksoy, H Serdar Akyüz, Matthieu Ferry, Aynur Dikbaş, Erhan Altunel To cite this version: Mustapha Meghraoui, M. Ersen Aksoy, H Serdar Akyüz, Matthieu Ferry, Aynur Dikbaş, et al.. Pale- oseismology of the North Anatolian Fault at Güzelköy (Ganos segment, Turkey): Size and recurrence time of earthquake ruptures west of the Sea of Marmara. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, AGU and the Geochemical Society, 2012, 10.1029/2011GC003960. hal-01264190 HAL Id: hal-01264190 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01264190 Submitted on 1 Feb 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Article Volume 13, Number 4 12 April 2012 Q04005, doi:10.1029/2011GC003960 ISSN: 1525-2027 Paleoseismology of the North Anatolian Fault at Güzelköy (Ganos segment, Turkey): Size and recurrence time of earthquake ruptures west of the Sea of Marmara Mustapha Meghraoui Institut de Physique du Globe de Strasbourg (UMR 7516), F-67084 Strasbourg, France ([email protected]) M. Ersen Aksoy Institut de Physique du Globe de Strasbourg (UMR 7516), F-67084 Strasbourg, France Eurasia Institute of Earth Sciences, Istanbul Technical University, 34469 Istanbul, Turkey Now at Instituto Dom Luiz, Universidade de Lisboa, P-1750-129 Lisbon, Portugal H. -

Separating Fact from Fiction in the Aiolian Migration

hesperia yy (2008) SEPARATING FACT Pages399-430 FROM FICTION IN THE AIOLIAN MIGRATION ABSTRACT Iron Age settlementsin the northeastAegean are usuallyattributed to Aioliancolonists who journeyed across the Aegean from mainland Greece. This articlereviews the literary accounts of the migration and presentsthe relevantarchaeological evidence, with a focuson newmaterial from Troy. No onearea played a dominantrole in colonizing Aiolis, nor is sucha widespread colonizationsupported by the archaeologicalrecord. But the aggressive promotionof migrationaccounts after the PersianWars provedmutually beneficialto bothsides of theAegean and justified the composition of the Delian League. Scholarlyassessments of habitation in thenortheast Aegean during the EarlyIron Age are remarkably consistent: most settlements are attributed toAiolian colonists who had journeyed across the Aegean from Thessaly, Boiotia,Akhaia, or a combinationof all three.1There is no uniformityin theancient sources that deal with the migration, although Orestes and his descendantsare named as theleaders in mostaccounts, and are credited withfounding colonies over a broadgeographic area, including Lesbos, Tenedos,the western and southerncoasts of theTroad, and theregion betweenthe bays of Adramyttion and Smyrna(Fig. 1). In otherwords, mainlandGreece has repeatedly been viewed as theagent responsible for 1. TroyIV, pp. 147-148,248-249; appendixgradually developed into a Mountjoy,Holt Parker,Gabe Pizzorno, Berard1959; Cook 1962,pp. 25-29; magisterialstudy that is includedhere Allison Sterrett,John Wallrodt, Mal- 1973,pp. 360-363;Vanschoonwinkel as a companionarticle (Parker 2008). colm Wiener, and the anonymous 1991,pp. 405-421; Tenger 1999, It is our hope that readersinterested in reviewersfor Hesperia. Most of trie pp. 121-126;Boardman 1999, pp. 23- the Aiolian migrationwill read both articlewas writtenin the Burnham 33; Fisher2000, pp. -

Flowers in Greek Mythology

Flowers in Greek Mythology Everybody knows how rich and exciting Greek Mythology is. Everybody also knows how rich and exciting Greek Flora is. Find out some of the famous Greek myths flower inspired. Find out how feelings and passions were mixed together with flowers to make wonderful stories still famous in nowadays. Anemone:The name of the plant is directly linked to the well known ancient erotic myth of Adonis and Aphrodite (Venus). It has been inspired great poets like Ovidius or, much later, Shakespeare, to compose hymns dedicated to love. According to this myth, while Adonis was hunting in the forest, the ex- lover of Aphrodite, Ares, disguised himself as a wild boar and attacked Adonis causing him lethal injuries. Aphrodite heard the groans of Adonis and rushed to him, but it was too late. Aphrodite got in her arms the lifeless body of her beloved Adonis and it is said the she used nectar in order to spray the wood. The mixture of the nectar and blood sprang a beautiful flower. However, the life of this 1 beautiful flower doesn’t not last. When the wind blows, makes the buds of the plant to bloom and then drifted away. This flower is called Anemone because the wind helps the flowering and its decline. Adonis:It would be an omission if we do not mention that there is a flower named Adonis, which has medicinal properties. According to the myth, this flower is familiar to us as poppy meadows with the beautiful red colour. (Adonis blood). Iris: The flower got its name from the Greek goddess Iris, goddess of the rainbow. -

The Greek World

THE GREEK WORLD THE GREEK WORLD Edited by Anton Powell London and New York First published 1995 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. Disclaimer: For copyright reasons, some images in the original version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 First published in paperback 1997 Selection and editorial matter © 1995 Anton Powell, individual chapters © 1995 the contributors All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Greek World I. Powell, Anton 938 Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data The Greek world/edited by Anton Powell. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Greece—Civilization—To 146 B.C. 2. Mediterranean Region— Civilization. 3. Greece—Social conditions—To 146 B.C. I. Powell, Anton. DF78.G74 1995 938–dc20 94–41576 ISBN 0-203-04216-6 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-16276-5 (Adobe eReader Format) ISBN 0-415-06031-1 (hbk) ISBN 0-415-17042-7 (pbk) CONTENTS List of Illustrations vii Notes on Contributors viii List of Abbreviations xii Introduction 1 Anton Powell PART I: THE GREEK MAJORITY 1 Linear -

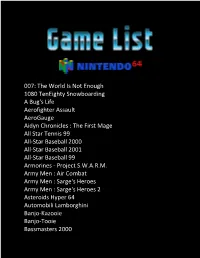

007: the World Is Not Enough 1080 Teneighty Snowboarding a Bug's

007: The World Is Not Enough 1080 TenEighty Snowboarding A Bug's Life Aerofighter Assault AeroGauge Aidyn Chronicles : The First Mage All Star Tennis 99 All-Star Baseball 2000 All-Star Baseball 2001 All-Star Baseball 99 Armorines - Project S.W.A.R.M. Army Men : Air Combat Army Men : Sarge's Heroes Army Men : Sarge's Heroes 2 Asteroids Hyper 64 Automobili Lamborghini Banjo-Kazooie Banjo-Tooie Bassmasters 2000 Batman Beyond : Return of the Joker BattleTanx BattleTanx - Global Assault Battlezone : Rise of the Black Dogs Beetle Adventure Racing! Big Mountain 2000 Bio F.R.E.A.K.S. Blast Corps Blues Brothers 2000 Body Harvest Bomberman 64 Bomberman 64 : The Second Attack! Bomberman Hero Bottom of the 9th Brunswick Circuit Pro Bowling Buck Bumble Bust-A-Move '99 Bust-A-Move 2: Arcade Edition California Speed Carmageddon 64 Castlevania Castlevania : Legacy of Darkness Chameleon Twist Chameleon Twist 2 Charlie Blast's Territory Chopper Attack Clay Fighter : Sculptor's Cut Clay Fighter 63 1-3 Command & Conquer Conker's Bad Fur Day Cruis'n Exotica Cruis'n USA Cruis'n World CyberTiger Daikatana Dark Rift Deadly Arts Destruction Derby 64 Diddy Kong Racing Donald Duck : Goin' Qu@ckers*! Donkey Kong 64 Doom 64 Dr. Mario 64 Dual Heroes Duck Dodgers Starring Daffy Duck Duke Nukem : Zero Hour Duke Nukem 64 Earthworm Jim 3D ECW Hardcore Revolution Elmo's Letter Adventure Elmo's Number Journey Excitebike 64 Extreme-G Extreme-G 2 F-1 World Grand Prix F-Zero X F1 Pole Position 64 FIFA 99 FIFA Soccer 64 FIFA: Road to World Cup 98 Fighter Destiny 2 Fighters -

Renaissance Receptions of Ovid's Tristia Dissertation

RENAISSANCE RECEPTIONS OF OVID’S TRISTIA DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Gabriel Fuchs, M.A. Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Frank T. Coulson, Advisor Benjamin Acosta-Hughes Tom Hawkins Copyright by Gabriel Fuchs 2013 ABSTRACT This study examines two facets of the reception of Ovid’s Tristia in the 16th century: its commentary tradition and its adaptation by Latin poets. It lays the groundwork for a more comprehensive study of the Renaissance reception of the Tristia by providing a scholarly platform where there was none before (particularly with regard to the unedited, unpublished commentary tradition), and offers literary case studies of poetic postscripts to Ovid’s Tristia in order to explore the wider impact of Ovid’s exilic imaginary in 16th-century Europe. After a brief introduction, the second chapter introduces the three major commentaries on the Tristia printed in the Renaissance: those of Bartolomaeus Merula (published 1499, Venice), Veit Amerbach (1549, Basel), and Hecules Ciofanus (1581, Antwerp) and analyzes their various contexts, styles, and approaches to the text. The third chapter shows the commentators at work, presenting a more focused look at how these commentators apply their differing methods to the same selection of the Tristia, namely Book 2. These two chapters combine to demonstrate how commentary on the Tristia developed over the course of the 16th century: it begins from an encyclopedic approach, becomes focused on rhetoric, and is later aimed at textual criticism, presenting a trajectory that ii becomes increasingly focused and philological. -

Identity Crisis: Scriptae Personae in Ovid's Amores

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KU ScholarWorks IDENTITY CRISIS: SCRIPTAE PERSONAE IN OVID’S AMORES 1.4 AND 2.5 BY Monique Imair Submitted to the graduate degree program in Classics and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Tara Welch, Chairperson Committee Members : Michael Shaw Pamela Gordon Date Defended: 04/01/2011 The Thesis Committee for Monique S. Imair certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: IDENTITY CRISIS: SCRIPTAE PERSONAE IN OVID’S AMORES 1.4 AND 2.5 Tara Welch, Chairperson Committee Members : Michael Shaw Pamela Gordon Date Accepted: 06/13/2011 ii Page left intentionally blank iii Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to discuss the multifaceted personae of Ovid’s Amores, specifically in Amores 1.4 and 2.5. These personae range from Ovid as poet (poeta), lover (amator), and love teacher (praeceptor amoris); the poet’s love interest, the puella; the rival, the vir; other unnamed rivals; and reader. I argue that Ovid complicates the roles of the personae in his poetry by means of subversion, inversion and amalgamation. Furthermore, I conclude that as readers, when we understand how these personae interact with each other and ourselves (as readers), we can better comprehend Ovid’s poetry and quite possibly gain some insight into his other poetic works. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter One. Introduction 1 Chapter Two. Personae in Amores 1.4 12 Chapter Three. -

A Stranger in a Strange Land: Medea in Roman Republican Tragedy1 Robert Cowan

CHAPTER 3 A Stranger in a Strange Land: Medea in Roman Republican Tragedy1 Robert Cowan The first performance of a Roman version of a Greek tragedy in 240 BC was a momentous event. It was not the beginning of Roman appropriation of Greek culture- Rome had had contact and complex interaction with Greek communities in Magna Graecia and elsewhere from earliest times - but it was an important landmark in the relationship between Greece and Rome. 2 When a tragedy by Livius Andronicus was performed to celebrate victory over Carthage in the First Punic War, a central cultural practice of an alien culture was adopted, adapted, appropriated and transformed to serve as a central cultural practice of Rome. It is significant that the first tragedy celebrated a victory (albeit over Carthage), since the appropriation of Greek tragedy was an act of cultural conquest, as Roman actors marched into and occupied the stage of Attic drama. Yet the event was more complex than that description suggests. In Horace's phrase, captured Greece captured its savage master.3 The writing ofRoman tragedy in the Greek style was simultaneously an act of self-confident literary invasion and of cultural submission to the thrall of a more established theatrical tradition. In terms of literary history, this complex interrelationship marks the beginning of Latin literature, in conjunction with Livius's Latin, Saturnian version of the Odyssey. In terms of culture, the flourishing of Roman drama coincided with the massive expansion of Roman territory and the accompanying challenge to its sense of identity. Dramas were performed at public festivals, /rrdi scaenici, organized by state officials, the aediles, and sponsored by influential elites.