Breaching the Bronze Wall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHESS REVIEW but We Can Give a Bit More in a Few 250 West 57Th St Reet , New York 19, N

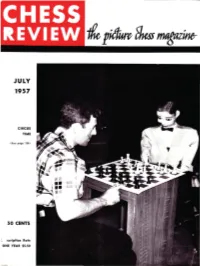

JULY 1957 CIRCUS TIME (See page 196 ) 50 CENTS ~ scription Rate ONE YEAR $5.50 From the "Amenities and Background of Chess-Play" by Ewart Napier ECHOES FROM THE PAST From Leipsic Con9ress, 1894 An Exhibition Game Almos t formidable opponent was P aul Lipk e in his pr ime, original a nd pi ercing This instruc tive game displays these a nd effective , Quite typica l of 'h is temper classical rivals in holiUay mood, ex is the ",lid Knigh t foray a t 8. Of COU I'se, ploring a dangerous Queen sacrifice. the meek thil'd move of Black des e r\" e~ Played at Augsburg, Germany, i n 1900, m uss ing up ; Pillsbury adopted t he at thirty moves an hOlll" . Tch igorin move, 3 . N- B3. F A L K BEE R COU NT E R GAM BIT Q U EE N' S PAW N GA ME" 0 1'. E. Lasker H. N . Pi llsbury p . Li pke E. Sch iffers ,Vhite Black W hite Black 1 P_K4 P-K4 9 8-'12 B_ KB4 P_Q4 6 P_ KB4 2 P_KB4 P-Q4 10 0-0- 0 B,N 1 P-Q4 8-K2 Mate announred in eight. 2 P- K3 KN_ B3 7 N_ R3 3 P xQP P-K5 11 Q- N4 P_ K B4 0 - 0 8 N_N 5 K N_B3 12 Q-N3 N-Q2 3 B-Q3 P- K 3? P-K R3 4 Q N- B3 p,p 5 Q_ K2 B-Q3 13 8-83 N-B3 4 N-Q2 P-B4 9 P-K R4 6 P_Q3 0-0 14 N-R3 N_ N5 From Leipsic Con9ress. -

Art. I.—On the Persian Game of Chess

JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY. ART. I.— On the Persian Game of Chess. By K BLAND, ESQ., M.R.A.S. [Read June 19th, 1847.] WHATEVER difference of opinion may exist as to the introduction of Chess into Europe, its Asiatic origin is undoubted, although the question of its birth-place is still open to discussion, and will be adverted to in this essay. Its more immediate design, however, is to illustrate the principles and practice of the game itself from such Oriental sources as have hitherto escaped observation, and, especially, to introduce to particular notice a variety of Chess which may, on fair grounds, be considered more ancient than that which is now generally played, and lead to a theory which, if it should be esta- blished, would materially affect our present opinions on its history. In the life of Timur by Ibn Arabshah1, that conqueror, whose love of chess forms one of numerous examples among the great men of all nations, is stated to have played, in preference, at a more complicated game, on a larger board, and with several additional pieces. The learned Dr. Hyde, in his valuable Dissertation on Eastern Games2, has limited his researches, or, rather, been restricted in them by the nature of his materials, to the modern Chess, and has no further illustrated the peculiar game of Timur than by a philological Edited by Manger, "Ahmedis ArabsiadEe Vitae et Rernm Gestarum Timuri, qui vulgo Tamerlanes dicitur, Historia. Leov. 1772, 4to;" and also by Golius, 1736, * Syntagma Dissertationum, &c. Oxon, MDCCJ-XVII., containing "De Ludis Orientalibus, Libri duo." The first part is " Mandragorias, seu Historia Shahi. -

Chapter 15, New Pieces

Chapter 15 New pieces (2) : Pieces with limited range [This chapter covers pieces whose range of movement is limited, in the same way that the moves of the king and knight are limited in orthochess.] 15.1 Pieces which can move only one square [The only such piece in orthochess is the king, but the ‘wazir’ (one square orthogonally in any direction), ‘fers’ or ‘firzan’ (one square diagonally in any direction), ‘gold general’ (as wazir and also one square diagonally forward), and ‘silver general’ (as fers and also one square orthogonally forward), have been widely used and will be found in many of the games in the chapters devoted to historical and regional versions of chess. Some other flavours will be found below. In general, games which involve both a one-square mover and ‘something more powerful’ will be found in the section devoted to ‘something more powerful’, but the two later developments of ‘Le Jeu de la Guerre’ are included in this first section for convenience. One-square movers are slow and may seem to be weak, but even the lowly fers can be a potent attacking weapon. ‘Knight for two pawns’ is rarely a good swap, but ‘fers for two pawns’ is a different matter, and a sound tactic, when unobservant defence permits it, is to use the piece with a fers move to smash a hole in the enemy pawn structure so that other men can pour through. In xiangqi (Chinese chess) this piece is confined to a defensive role by the rules of the game, but to restrict it to such a role in other forms of chess may well be a losing strategy.] Le Jeu de la Guerre [M.M.] (‘M.M.’, ranks 1/11, CaHDCuGCaGCuDHCa on ranks perhaps J. -

Evaluating Chess-Like Games Using Generated Natural Language Descriptions

Evaluating Chess-like Games Using Generated Natural Language Descriptions Jakub Kowalski?, Łukasz Żarczyński, and Andrzej Kisielewicz?? 1 Institute of Computer Science, University of Wrocław, [email protected] 2 Institute of Computer Science, University of Wrocław, [email protected] 3 Institute of Mathematics, University of Wrocław, [email protected] Abstract. We continue our study of the chess-like games defined as the class of Simplified Boardgames. We present an algorithm generating natural language descriptions of piece movements that can be used as a tool not only for explaining them to the human player, but also for the task of procedural game generation using an evolutionary approach. We test our algorithm on some existing human-made and procedurally generated chess-like games. 1 Introduction The task of Procedural Content Generation (PCG) [1] is to create digital content using algorithmic methods. In particular, the domain of games is the area, where PCG is used for creating various elements including names, maps, textures, music, enemies, or even missions. The most sophisticated and complex goal is to create the complete rules of a game [2–4]. Designing a game generation algorithm requires restricting the set of possible games to some well defined domain. This places the task into the area of General Game Playing, i.e. the art of designing programs which can play any game from some fixed class of games. The use of PCG in General Game Playing begins with the Pell’s Metagame system [5], describing the so-called Symmetric Chess-like Games. The evaluation of the quality of generated games was left entirely for the human expert. -

The Aesthetics of Islamic Architecture & the Exuberance of Mamluk Design

The Aesthetics of Islamic Architecture & The Exuberance of Mamluk Design Tarek A. El-Akkad Dipòsit Legal: B. 17657-2013 ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tesisenxarxa.net) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX. No s’autoritza la presentació del s eu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tesisenred.net) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR. No se autoriza la presentación de su contenido en una ventana o marco ajeno a TDR (framing). Esta reserva de derechos afecta tanto al resumen de presentación de la tesis como a sus contenidos. -

Chess Pieces Names

Names of Chess Pieces in International Languages Information by Elke Rehder for the special website http://www.schach-chess.com Chess Pieces international names Chess is an international sport. The names of the chess pieces are translated into several languages. For mobile devices such as smartphones and tablets I have created the following three tables. The first part shows the translation for the chess pieces king, queen and rook. The second part is for the chess pieces bishop, knight and pawn. The third table shows the international translation for the expressions chess, check and checkmate with links to the corresponding Wikipedia websites. Part 1: Translation King, Queen, Rook © Elke Rehder English K king Q queen R rook Albanian M Mbret M Mbretëreshë T Top ر رخ/طاب ية و وزي ر م ِكل َ Arabic Ц Цар Т Топ Bulgarian Д Дама (Dama) (Zar) (Top) Catalan R rei D dama T torre Chinese K 王 Q 后 R 車 D dama / Croatian K kralj T top/kula kraljica Czech K král D dáma V věž Danish K konge D dronning T tårn Dutch K koning D dame T toren Esperanto R reĝo D damo T turo Estonian K kuningas L lipp V vanker Farsi S Schah W Wazir R Ruch D daami / Finn K kuningas T torni kuningatar French R roi D dame T tour German K König D Dame T Turm T teyrn / Gaeilge B brenhines C castell brenin Greek Ρ βασιλιάς Β βασίλισσα Π πύργος צריח מלכה מלך Hebrew Hindi R raja V vajeer H hathi Hungaria K király V vezér B bástya Icelandic K kóngur D drottning H hrókur Indonesia R raja M menteri B benteng Irish R rí B banríon C caiseal Italian R re D donna T torre Japanese キング クイーン ルーク Korean K 킹 Q 퀸 R 룩 Latin K rex Q regina R turris Latvian K karalis D dāma T tornis Lithuanian K karalius V valdovė B bokštas Luxemb. -

White Knight Review September-October- 2010

Chess Magazine Online E-Magazine Volume 1 • Issue 1 September October 2010 Nobel Prize winners and Chess The Fischer King: The illusive life of Bobby Fischer Pt. 1 Sight Unseen-The Art of Blindfold Chess CHESS- theres an app for that! TAKING IT TO THE STREETS Street Players and Hustlers White Knight Review September-October- 2010 White My Move [email protected] Knight editorial elcome to our inaugural Review WIssue of White Knight Review. This chess magazine Chess E-Magazine was the natural outcome of the vision of 3 brothers. The unique corroboration and the divers talent of the “Wall boys” set in motion the idea of putting together this White Knight Table of Contents contents online publication. The oldest of the three is my brother Bill. He Review EDITORIAL-”My Move” 3 is by far the Chess expert of the group being the Chess E-Magazine author of over 30 chess books, several websites on the internet and a highly respected player in FEATURE-Taking it to the Streets 4 the chess world. His books and articles have spanned the globe and have become a wellspring of knowledge for both beginners and Executive Editor/Writer BOOK REVIEW-Diary of a Chess Queen 7 masters alike. Bill Wall Our younger brother is the entrepreneur [email protected] who’s initial idea of a marketable website and HISTORY-The History of Blindfold Chess 8 promoting resource material for chess players became the beginning focus on this endeavor. His sales and promotion experience is an FEATURE-Chessman- Picking up the pieces 10 integral part to the project. -

VARIANT CHESS 8 Page 97

July-December 1992 VARIANT CHESS 8 page 97 @ Copyright. 1992. rssN 0958-8248 Publisher and Editor G. P. Jelliss 99 Bohemia Road Variant Chess St Leonards on Sea TN37 6RJ (rJ.K.) In this issue: Hexagonal Chess, Modern Courier Chess, Escalation, Games Consultant Solutions, Semi-Pieces, Variants Duy, Indexes, New Editor/Publisher. Malcolm Horne Volume 1 complete (issues 1-8, II2 pages, A4 size, unbound): f10. 10B Windsor Square Exmouth EX8 1JU New Varieties of Hexagonal Chess find that we need 8 pawns on the second rank plus by G. P. Jelliss 5 on the third rank. I prefer to add 2 more so that there are 5 pawns on each colour, and the rooks are Various schemes have been proposed for playing more securely blocked in. There is then one pawn in chess on boards on which the cells are hexagons each file except the edge files. A nm being a line of instead of squares. A brief account can be found in cells perpendicular to the base-line. The Oxford Companion to Chess 1984 where games Now how should the pawns move? If they are to by Siegmund Wellisch I9L2, H.D.Baskerville L929, continue to block the files we must allow them only Wladyslaw Glinski L949 and Anthony Patton L975 to move directly forward. This is a fers move. For are mentioned. To these should be added the variety their capture moves we have choices: the other two by H. E. de Vasa described in Joseph Boyer's forward fers moves, or the two forward wazit NouveoLx, Jeux d'Ecltecs Non Orthodoxes 1954 moves, or both. -

The Symbolism of Chess by Titus Burckhardt

The Symbolism of Chess by Titus Burckhardt Studies in Comparative Religion, Vol. 3, No. 2. (Spring, 1969) © World Wisdom, Inc. www.studiesincomparativereligion.com IT is known that the game of chess originated in India. It was passed on to the medieval West through the intermediary of the Persians and the Arabs, a fact to which we owe, for example, the expression "check-mate", (German: Schachmatt) which is derived from the Persian shah: "king" and the Arabic mat: "he is dead". At the time of the Renaissance some of the rules of the game were changed: the “queen”1 and the two “bishops”2 were given a greater mobility, and thenceforth the game acquired a more abstract and mathematical character; it departed from its concrete model strategy, without however losing the essential features of its symbolism. In the original position of the chessmen, the ancient strategic model remains obvious; one can recognize the two armies ranged according to the battle order which was customary in the ancient East: the light troops, represented by the pawns, form the first line ; the bulk of the army consists of the heavy troops, the war chariots ("castles"), the knights ("cavalry") and the war elephants ("bishops"); the "king" with his "lady" or "counsellor" is positioned at the centre of his troops. The form of the chess-board corresponds to the "classical" type of Vāstu-mandala, the diagram which also constitutes the basic layout of a temple or a city. It has been pointed out3 that this diagram symbolizes existence conceived as a "field of action" of the divine powers. -

The Classified Encyclopedia of Chess Variants

THE CLASSIFIED ENCYCLOPEDIA OF CHESS VARIANTS I once read a story about the discovery of a strange tribe somewhere in the Amazon basin. An eminent anthropologist recalls that there was some evidence that a space ship from Mars had landed in the area a millenium or two earlier. ‘Good heavens,’ exclaims the narrator, are you suggesting that this tribe are the descendants of Martians?’ ‘Certainly not,’ snaps the learned man, ‘they are the original Earth-people — it is we who are the Martians.’ Reflect that chess is but an imperfect variant of a game that was itself a variant of a germinal game whose origins lie somewhere in the darkness of time. The Classified Encyclopedia of Chess Variants D. B. Pritchard The second edition of The Encyclopedia of Chess Variants completed and edited by John Beasley Copyright © the estate of David Pritchard 2007 Published by John Beasley 7 St James Road Harpenden Herts AL5 4NX GB - England ISBN 978-0-9555168-0-1 Typeset by John Beasley Originally printed in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd, King’s Lynn Contents Introduction to the second edition 13 Author’s acknowledgements 16 Editor’s acknowledgements 17 Warning regarding proprietary games 18 Part 1 Games using an ordinary board and men 19 1 Two or more moves at a time 21 1.1 Two moves at a turn, intermediate check observed 21 1.2 Two moves at a turn, intermediate check ignored 24 1.3 Two moves against one 25 1.4 Three to ten moves at a turn 26 1.5 One more move each time 28 1.6 Every man can move 32 1.7 Other kinds of multiple movement 32 2 Games with concealed -

Chapter 34, Games Using a Single Square Or Rectangular Board

Chapter 34 Games using a single square or rectangular board [Although what became the standard single-board four-handed game used a board with extensions, the earliest known four-handed game used a standard 8x8 board, and it is convenient to consider this and other such games first.] 34.1 Classical Indian four-player games Chaturaji, also known as The Game Of The promote and is rendered immobile. However, Four Kings. Four-handed Indian game, once if a player is reduced to a P, or a P and a B, thought to be the germinal chess game and then the P can promote to any piece (including associated with Chaturanga. The first firm a K) on any end square. Kings are subject to reference to it is now believed to be about 11th capture like other pieces. The object of the century. The game could be partnership or all- game is to earn points by capturing opposing against-all; it could be played with or without kings and/or occupying the throne square of a dice, or with dice determining the opening rival. A player occupying the throne of an ally moves only. Turn of play was clockwise. Each takes over his partner’s forces. An exchange side has four pieces, Rajah (K), Elephant (R), of captured kings could be agreed between Horse (N) and Boat (B) and in addition four opponents, the kings then being restored to Soldiers (P). As usually given, the pawns were their original squares. A player with a bare placed on a2-d2, g1-g4, h7-e7, and b8-b5, with king could then retire honourably (draw). -

Chess Club Champion

MAY 1957 MARSHALL CHESS CLUB CHAMPION l :;e~ " New Y orle " in " W o r ld of Che .... pagel ) 50 CENTS ... 4bsc:ription Rote ONE YEAR $5.50 From the "Amenities and Background of Chess-Play" by m Ewart Napier The Incomparable Twins First Game 23 , . , Q- D5 be fol'e t he nook mo,'e is betlel', When PlIIs bu ry I'eached America afte r St, Pet ersburg. 1896 the 1896 Qu adl'ans ulal' event at St, P e, QUEEN'S GAMBIT DECLINED 23 R- Q2 R- B5 23 Q-B5 Q- BS 24 KR_Ql R- B6 25 K _N2 . , tersburg, w here he {ailed ilgainst St ein Pillsbury Dl" Lask~r . Hz, while winning a majority of the glori, White Blacl; White ml ~se (1 ::6 Q- N l with drawing ous six gam e series from Champion Dr, hopes. 1 P_Q4 P-Q4 4 N_B3 P-B4 Lasker, I wall invJled to his lodging in 26 .. ., RxP ~! 2 P-QB4 P-K3 5 B_ N5 B P xP New Yor k, 27 Q-K6t K _R2 3 N-QB3 N- KB3 6 QxP N-B3 A fter congratula tions, his first q ues, The clll'laill goes down o n a b i ~ ban Ie. tion was " Of COIlI'Se , you saw the StH' not w ho lly free from such errol' as ('omes prlsing Quee n Ga m bit Declined 1.... 1s ker \\'ith t he llme,lImlt. wo n rrom me! I had. And what had been 28 KxR Q-B6t my re'ac tions? Althoug h I k new not e nough to II r glie t he point, I !l aid there mus t be something radically wrong wllh opening play tha t left Ihe King Dls hop at home for 21 moves and that a s a preachment on premature ilttilck, Uij well a s fOr PI'OfUIHJ!ty and beauty, it was the s martest of all gumes.