Art. I.—On the Persian Game of Chess

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fide Online Chess Regulations

Annex 6.4 FIDE ONLINE CHESS REGULATIONS Introduction The FIDE Online Chess Regulations are intended to cover all competitions where players play on the virtual chessboard and transmit moves via the internet. Wherever possible, these Regulations are intended to be identical to the FIDE Laws of Chess and related FIDE competition regulations. They are intended for use by players and arbiters in official FIDE online competitions, and as a technical specification for online chess platforms hosting these competitions. These Regulations cannot cover all possible situations that may arise during a competition, but it should be possible for an arbiter with the necessary competence, sound judgment, and objectivity, to arrive at the correct decision based on his/her understanding of these Regulations. Annex 6.4 Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Part I: Basic Rules of Play ................................................................................................................. 3 Article 1: Application of the FIDE Laws of Chess .............................................................................. 3 Part II: Online Chess Rules ............................................................................................................... 3 Article 2: Playing Zone ................................................................................................................... 3 Article 3: Moving the Pieces on -

A Combinatorial Game Theoretic Analysis of Chess Endgames

A COMBINATORIAL GAME THEORETIC ANALYSIS OF CHESS ENDGAMES QINGYUN WU, FRANK YU,¨ MICHAEL LANDRY 1. Abstract In this paper, we attempt to analyze Chess endgames using combinatorial game theory. This is a challenge, because much of combinatorial game theory applies only to games under normal play, in which players move according to a set of rules that define the game, and the last player to move wins. A game of Chess ends either in a draw (as in the game above) or when one of the players achieves checkmate. As such, the game of chess does not immediately lend itself to this type of analysis. However, we found that when we redefined certain aspects of chess, there were useful applications of the theory. (Note: We assume the reader has a knowledge of the rules of Chess prior to reading. Also, we will associate Left with white and Right with black). We first look at positions of chess involving only pawns and no kings. We treat these as combinatorial games under normal play, but with the modification that creating a passed pawn is also a win; the assumption is that promoting a pawn will ultimately lead to checkmate. Just using pawns, we have found chess positions that are equal to the games 0, 1, 2, ?, ", #, and Tiny 1. Next, we bring kings onto the chessboard and construct positions that act as game sums of the numbers and infinitesimals we found. The point is that these carefully constructed positions are games of chess played according to the rules of chess that act like sums of combinatorial games under normal play. -

Computer Analysis of World Chess Champions 65

Computer Analysis of World Chess Champions 65 COMPUTER ANALYSIS OF WORLD CHESS CHAMPIONS1 Matej Guid2 and Ivan Bratko2 Ljubljana, Slovenia ABSTRACT Who is the best chess player of all time? Chess players are often interested in this question that has never been answered authoritatively, because it requires a comparison between chess players of different eras who never met across the board. In this contribution, we attempt to make such a comparison. It is based on the evaluation of the games played by the World Chess Champions in their championship matches. The evaluation is performed by the chess-playing program CRAFTY. For this purpose we slightly adapted CRAFTY. Our analysis takes into account the differences in players' styles to compensate the fact that calm positional players in their typical games have less chance to commit gross tactical errors than aggressive tactical players. Therefore, we designed a method to assess the difculty of positions. Some of the results of this computer analysis might be quite surprising. Overall, the results can be nicely interpreted by a chess expert. 1. INTRODUCTION Who is the best chess player of all time? This is a frequently posed and interesting question, to which there is no well founded, objective answer, because it requires a comparison between chess players of different eras who never met across the board. With the emergence of high-quality chess programs a possibility of such an objective comparison arises. However, so far computers were mostly used as a tool for statistical analysis of the players' results. Such statistical analyses often do neither reect the true strengths of the players, nor do they reect their quality of play. -

White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents

Chess E-Magazine Interactive E-Magazine Volume 3 • Issue 1 January/February 2012 Chess Gambits Chess Gambits The Immortal Game Canada and Chess Anderssen- Vs. -Kieseritzky Bill Wall’s Top 10 Chess software programs C Seraphim Press White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents Editorial~ “My Move” 4 contents Feature~ Chess and Canada 5 Article~ Bill Wall’s Top 10 Software Programs 9 INTERACTIVE CONTENT ________________ Feature~ The Incomparable Kasparov 10 • Click on title in Table of Contents Article~ Chess Variants 17 to move directly to Unorthodox Chess Variations page. • Click on “White Feature~ Proof Games 21 Knight Review” on the top of each page to return to ARTICLE~ The Immortal Game 22 Table of Contents. Anderssen Vrs. Kieseritzky • Click on red type to continue to next page ARTICLE~ News Around the World 24 • Click on ads to go to their websites BOOK REVIEW~ Kasparov on Kasparov Pt. 1 25 • Click on email to Pt.One, 1973-1985 open up email program Feature~ Chess Gambits 26 • Click up URLs to go to websites. ANNOTATED GAME~ Bareev Vs. Kasparov 30 COMMENTARY~ “Ask Bill” 31 White Knight Review January/February 2012 White Knight Review January/February 2012 Feature My Move Editorial - Jerry Wall [email protected] Well it has been over a year now since we started this publication. It is not easy putting together a 32 page magazine on chess White Knight every couple of months but it certainly has been rewarding (maybe not so Review much financially but then that really never was Chess E-Magazine the goal). -

Games Ancient and Oriental and How to Play Them, Being the Games Of

CO CD CO GAMES ANCIENT AND ORIENTAL AND HOW TO PLAY THEM. BEING THE GAMES OF THE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS THE HIERA GRAMME OF THE GREEKS, THE LUDUS LATKUNCULOKUM OF THE ROMANS AND THE ORIENTAL GAMES OF CHESS, DRAUGHTS, BACKGAMMON AND MAGIC SQUAEES. EDWARD FALKENER. LONDON: LONGMANS, GEEEN AND Co. AND NEW YORK: 15, EAST 16"' STREET. 1892. All rights referred. CONTENTS. I. INTRODUCTION. PAGE, II. THE GAMES OF THE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS. 9 Dr. Birch's Researches on the games of Ancient Egypt III. Queen Hatasu's Draught-board and men, now in the British Museum 22 IV. The of or the of afterwards game Tau, game Robbers ; played and called by the same name, Ludus Latrunculorum, by the Romans - - 37 V. The of Senat still the modern and game ; played by Egyptians, called by them Seega 63 VI. The of Han The of the Bowl 83 game ; game VII. The of the Sacred the Hiera of the Greeks 91 game Way ; Gramme VIII. Tlie game of Atep; still played by Italians, and by them called Mora - 103 CHESS. IX. Chess Notation A new system of - - 116 X. Chaturanga. Indian Chess - 119 Alberuni's description of - 139 XI. Chinese Chess - - - 143 XII. Japanese Chess - - 155 XIII. Burmese Chess - - 177 XIV. Siamese Chess - 191 XV. Turkish Chess - 196 XVI. Tamerlane's Chess - - 197 XVII. Game of the Maharajah and the Sepoys - - 217 XVIII. Double Chess - 225 XIX. Chess Problems - - 229 DRAUGHTS. XX. Draughts .... 235 XX [. Polish Draughts - 236 XXI f. Turkish Draughts ..... 037 XXIII. }\'ci-K'i and Go . The Chinese and Japanese game of Enclosing 239 v. -

Prusaprinters

Chinese Chess - Travel Size 3D MODEL ONLY Makerwiz VIEW IN BROWSER updated 6. 2. 2021 | published 6. 2. 2021 Summary This is a full set of Chinese Chess suitable for travelling. We shrunk down the original design to 60% and added a new lid with "Chinese Chess" in traditional Chinese characters. We also added a new chess board graphics file suitable for printing on paper or laser etching/cutting onto wood. Enjoy! Here is a brief intro about Chinese Chess from Wikipedia: 8C 68 "Xiangqi (Chinese: 61 CB ; pinyin: xiàngqí), also called Chinese chess, is a strategy board game for two players. It is one of the most popular board games in China, and is in the same family as Western (or international) chess, chaturanga, shogi, Indian chess and janggi. Besides China and areas with significant ethnic Chinese communities, xiangqi (cờ tướng) is also a popular pastime in Vietnam. The game represents a battle between two armies, with the object of capturing the enemy's general (king). Distinctive features of xiangqi include the cannon (pao), which must jump to capture; a rule prohibiting the generals from facing each other directly; areas on the board called the river and palace, which restrict the movement of some pieces (but enhance that of others); and placement of the pieces on the intersections of the board lines, rather than within the squares." Toys & Games > Other Toys & Games games chess Unassociated tags: Chinese Chess Category: Chess F3 Model Files (.stl, .3mf, .obj, .amf) 3D DOWNLOAD ALL FILES chinese_chess_box_base.stl 15.7 KB F3 3D updated 25. -

A Semiotic Analysis on Signs of the English Chess Game

1 A Semiotic Analysis on Signs of the English Chess Game M. I. Andi Purnomo, Drs. Wisasongko, M.A., Hat Pujiati, S.S., M.A. English Department, Faculty of Letter, Jember University Jln. Kalimantan 37, Jember 68121 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This thesis discusses about English Chess Game through Roland Barthes's Myth. In this thesis, I use documentary technique as method of analysis. The analysis is done by the observation of the rules, colors, and images of the English chess game. In addition, chessman and chess formation are analyzed using syntagmatic and paradigmatic relation theory to explore the correlation between symbols of the English chess game with the existence of Christian in the middle age of England. The result of this thesis shows the relation of English chess game with the history of England in the middle age where Christian ideology influences the social, military, and government political life of the English empire. Keywords: chessman, chess piece, bishops, king, knights, pawns, queen, rooks. Introduction Then, the game spread into Europe. Around 1200, the game was established in Britain and the name of “Chess” begins Game is an activity that is done by people for some (Shenk, 2006:51). It means chess spread to English during purposes. Some people use the game as a medium of the Middle Ages. The Middle Age of English begins around interaction with other people. Others use the game as the 1066 – 1485 (www.middle-ages.org.uk). At that time, the activity of spending leisure time. Others use the game as the Christian dominated the whole empire and automatically the major activity for professional. -

CHESS REVIEW but We Can Give a Bit More in a Few 250 West 57Th St Reet , New York 19, N

JULY 1957 CIRCUS TIME (See page 196 ) 50 CENTS ~ scription Rate ONE YEAR $5.50 From the "Amenities and Background of Chess-Play" by Ewart Napier ECHOES FROM THE PAST From Leipsic Con9ress, 1894 An Exhibition Game Almos t formidable opponent was P aul Lipk e in his pr ime, original a nd pi ercing This instruc tive game displays these a nd effective , Quite typica l of 'h is temper classical rivals in holiUay mood, ex is the ",lid Knigh t foray a t 8. Of COU I'se, ploring a dangerous Queen sacrifice. the meek thil'd move of Black des e r\" e~ Played at Augsburg, Germany, i n 1900, m uss ing up ; Pillsbury adopted t he at thirty moves an hOlll" . Tch igorin move, 3 . N- B3. F A L K BEE R COU NT E R GAM BIT Q U EE N' S PAW N GA ME" 0 1'. E. Lasker H. N . Pi llsbury p . Li pke E. Sch iffers ,Vhite Black W hite Black 1 P_K4 P-K4 9 8-'12 B_ KB4 P_Q4 6 P_ KB4 2 P_KB4 P-Q4 10 0-0- 0 B,N 1 P-Q4 8-K2 Mate announred in eight. 2 P- K3 KN_ B3 7 N_ R3 3 P xQP P-K5 11 Q- N4 P_ K B4 0 - 0 8 N_N 5 K N_B3 12 Q-N3 N-Q2 3 B-Q3 P- K 3? P-K R3 4 Q N- B3 p,p 5 Q_ K2 B-Q3 13 8-83 N-B3 4 N-Q2 P-B4 9 P-K R4 6 P_Q3 0-0 14 N-R3 N_ N5 From Leipsic Con9ress. -

Rules & Regulations for the Candidates Tournament of the FIDE

Rules & regulations for the Candidates Tournament of the FIDE World Championship cycle 2012-2014 1. Organisation 1. 1 The Candidates Tournament to determine the challenger for the 2014 World Chess Championship Match shall be organised in the first quarter of 2014 and represent an integral part of the World Chess Championship regulations for the cycle 2012- 2014. Eight (8) players will participate in the Candidates Tournament and the winner qualifies for the World Chess Championship Match in the first quarter of 2014. 1. 2 Governing Body: the World Chess Federation (FIDE). For the purpose of creating the regulations, communicating with the players and negotiating with the organisers, the FIDE President has nominated a committee, hereby called the FIDE Commission for World Championships and Olympiads (hereinafter referred to as WCOC) 1. 3 FIDE, or its appointed commercial agency, retains all commercial and media rights of the Candidates Tournament, including internet rights. These rights can be transferred to the organiser upon agreement. 1. 4 Upon recommendation by the WCOC, the body responsible for any changes to these Regulations is the FIDE Presidential Board. 1. 5 At any time in the course of the application of these Regulations, any circumstances that are not covered or any unforeseen event shall be referred to the President of FIDE for final decision. 2. Qualification for the 2014 Candidates Tournament The players who qualify for the Candidates Tournament are determined according to the following, in order of priority: 2. 1 World Championship Match 2013 - The player who lost the 2013 World Championship Match qualifies. 2. 2 World Cup 2013 - The two (2) top winners of the World Cup 2013 qualify. -

Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25

Title: Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25 Introduction The UCS contains symbols for the game of chess in the Miscellaneous Symbols block. These are used in figurine notation, a common variation on algebraic notation in which pieces are represented in running text using the same symbols as are found in diagrams. While the symbols already encoded in Unicode are sufficient for use in the orthodox game, they are insufficient for many chess problems and variant games, which make use of extended sets. 1. Fairy chess problems The presentation of chess positions as puzzles to be solved predates the existence of the modern game, dating back to the mansūbāt composed for shatranj, the Muslim predecessor of chess. In modern chess problems, a position is provided along with a stipulation such as “white to move and mate in two”, and the solver is tasked with finding a move (called a “key”) that satisfies the stipulation regardless of a hypothetical opposing player’s moves in response. These solutions are given in the same notation as lines of play in over-the-board games: typically algebraic notation, using abbreviations for the names of pieces, or figurine algebraic notation. Problem composers have not limited themselves to the materials of the conventional game, but have experimented with different board sizes and geometries, altered rules, goals other than checkmate, and different pieces. Problems that diverge from the standard game comprise a genre called “fairy chess”. Thomas Rayner Dawson, known as the “father of fairy chess”, pop- ularized the genre in the early 20th century. -

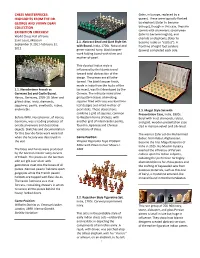

CHESS MASTERPIECES: (Later, in Europe, Replaced by a HIGHLIGHTS from the DR

CHESS MASTERPIECES: (later, in Europe, replaced by a HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE DR. queen). These were typically flanKed GEORGE AND VIVIAN DEAN by elephants (later to become COLLECTION bishops), though in this case, they are EXHIBITION CHECKLIST camels with drummers; cavalrymen (later to become Knights); and World Chess Hall of Fame chariots or elephants, (later to Saint Louis, Missouri 2.1. Abstract Bead anD Dart Style Set become rooKs or “castles”). A September 9, 2011-February 12, with BoarD, India, 1700s. Natural and frontline of eight foot soldiers 2012 green-stained ivory, blacK lacquer- (pawns) completed each side. work folding board with silver and mother-of-pearl. This classical Indian style is influenced by the Islamic trend toward total abstraction of the design. The pieces are all lathe- turned. The blacK lacquer finish, made in India from the husKs of the 1.1. Neresheimer French vs. lac insect, was first developed by the Germans Set anD Castle BoarD, Chinese. The intricate inlaid silver Hanau, Germany, 1905-10. Silver and grid pattern traces alternating gilded silver, ivory, diamonds, squares filled with lacy inscribed fern sapphires, pearls, amethysts, rubies, leaf designs and inlaid mother-of- and marble. pearl disKs. These decorations 2.3. Mogul Style Set with combine a grid of squares, common Presentation Case, India, 1800s. Before WWI, Neresheimer, of Hanau, to Western forms of chess, with Beryl with inset diamonds, rubies, Germany, was a leading producer of another grid of inlaid center points, and gold, wooden presentation case ornate silverware and decorative found in Japanese and Chinese clad in maroon velvet and silk-lined. -

Dvoretsky's Endgame Manual

Dvoretsky’s Endgame Manual Mark Dvoretsky Foreword by Artur Yusupov Preface by Jacob Aagaard 2003 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 Table of Contents Foreword 6 Preface 7 From the Author 8 Other Signs, Symbols, and Abbreviations 12 Chapter 1 PAWN ENDGAMES 13 Key Squares 13 Corresponding Squares 14 Opposition 14 Mined Squares 18 Triangulation 20 Other Cases of Correspondence 22 King vs. Passed Pawns 24 The Rule of the Square 24 Réti’s Idea 25 The Floating Square 27 Three Connected Pawns 28 Queen vs. Pawns 29 Knight or Center Pawn 29 Rook or Bishop’s Pawn 30 Pawn Races 32 The Active King 34 Zugzwang 34 Widening the Beachhead 35 The King Routes 37 Zigzag 37 The Pendulum 38 Shouldering 38 Breakthrough 40 The Outside Passed Pawn 44 Two Rook’s Pawns with an Extra Pawn on the Opposite Wing 45 The Protected Passed Pawn 50 Two Pawns to One 50 Multi-Pawn Endgames 50 Undermining 53 Two Connected Passed Pawns 54 Stalemate 55 The Stalemate Refuge 55 “Semi-Stalemate” 56 Reserve Tempi 57 Exploiting Reserve Tempi 57 Steinitz’s Rule 59 The g- and h-Pawns vs. h-Pawn 60 The f- and h-Pawns vs. h-Pawn 62 Both Sides have Reserve Tempi 65 Chapter 2 KNIGHT VS. PAWNS 67 1 King in the Corner 67 Mate 67 Drawn Positions 67 Knight vs. Rook Pawn 68 The Knight Defends the Pawn 70 Chapter 3 KNIGHT ENDGAMES 74 The Deflecting Knight Sacrifice 74 Botvinnik’s Formula 75 Pawns on the Same Side 79 Chapter 4 BISHOP VS.