Origins of Chess Protochess, 400 B.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computer Analysis of World Chess Champions 65

Computer Analysis of World Chess Champions 65 COMPUTER ANALYSIS OF WORLD CHESS CHAMPIONS1 Matej Guid2 and Ivan Bratko2 Ljubljana, Slovenia ABSTRACT Who is the best chess player of all time? Chess players are often interested in this question that has never been answered authoritatively, because it requires a comparison between chess players of different eras who never met across the board. In this contribution, we attempt to make such a comparison. It is based on the evaluation of the games played by the World Chess Champions in their championship matches. The evaluation is performed by the chess-playing program CRAFTY. For this purpose we slightly adapted CRAFTY. Our analysis takes into account the differences in players' styles to compensate the fact that calm positional players in their typical games have less chance to commit gross tactical errors than aggressive tactical players. Therefore, we designed a method to assess the difculty of positions. Some of the results of this computer analysis might be quite surprising. Overall, the results can be nicely interpreted by a chess expert. 1. INTRODUCTION Who is the best chess player of all time? This is a frequently posed and interesting question, to which there is no well founded, objective answer, because it requires a comparison between chess players of different eras who never met across the board. With the emergence of high-quality chess programs a possibility of such an objective comparison arises. However, so far computers were mostly used as a tool for statistical analysis of the players' results. Such statistical analyses often do neither reect the true strengths of the players, nor do they reect their quality of play. -

Combinatorics on the Chessboard

Combinatorics on the Chessboard Interactive game: 1. On regular chessboard a rook is placed on a1 (bottom-left corner). Players A and B take alternating turns by moving the rook upwards or to the right by any distance (no left or down movements allowed). Player A makes the rst move, and the winner is whoever rst reaches h8 (top-right corner). Is there a winning strategy for any of the players? Solution: Player B has a winning strategy by keeping the rook on the diagonal. Knight problems based on invariance principle: A knight on a chessboard has a property that it moves by alternating through black and white squares: if it is on a white square, then after 1 move it will land on a black square, and vice versa. Sometimes this is called the chameleon property of the knight. This is related to invariance principle, and can be used in problems, such as: 2. A knight starts randomly moving from a1, and after n moves returns to a1. Prove that n is even. Solution: Note that a1 is a black square. Based on the chameleon property the knight will be on a white square after odd number of moves, and on a black square after even number of moves. Therefore, it can return to a1 only after even number of moves. 3. Is it possible to move a knight from a1 to h8 by visiting each square on the chessboard exactly once? Solution: Since there are 64 squares on the board, a knight would need 63 moves to get from a1 to h8 by visiting each square exactly once. -

A Package to Print Chessboards

chessboard: A package to print chessboards Ulrike Fischer November 1, 2020 Contents 1 Changes 1 2 Introduction 2 2.1 Bugs and errors.....................................3 2.2 Requirements......................................4 2.3 Installation........................................4 2.4 Robustness: using \chessboard in moving arguments..............4 2.5 Setting the options...................................5 2.6 Saving optionlists....................................7 2.7 Naming the board....................................8 2.8 Naming areas of the board...............................8 2.9 FEN: Forsyth-Edwards Notation...........................9 2.10 The main parts of the board..............................9 3 Setting the contents of the board 10 3.1 The maximum number of fields........................... 10 1 3.2 Filling with the package skak ............................. 11 3.3 Clearing......................................... 12 3.4 Adding single pieces.................................. 12 3.5 Adding FEN-positions................................. 13 3.6 Saving positions..................................... 15 3.7 Getting the positions of pieces............................ 16 3.8 Using saved and stored games............................ 17 3.9 Restoring the running game.............................. 17 3.10 Changing the input language............................. 18 4 The look of the board 19 4.1 Units for lengths..................................... 19 4.2 Some words about box sizes.............................. 19 4.3 Margins......................................... -

Anything but Average Chess Classics and Off-Beat Problems by Chris Jones

06/140 Book review Werner Keym: Anything but Average Chess Classics and Off-beat Problems By Chris Jones Werner Keym’s book ‘Anything but Average – Chess Classics and Off-beat Problems’ was published in Goettingen (Germany) earlier this year. On 198 pages, it has 375 games, studies, problems, puzzles by 240 authors, 120 related problems, 180 additional diagrams. And it’s in English! For details see <http://www.berlinthema.de> and www.nightrider-unlimited.de. This is a book to gladden the hearts of all chess lovers, even those who usually have little or no interest in composed chess positions. A large part of the book is devoted to ‘The Classics’, beginning with classic games and then going on to classic studies and classic problems. The emphasis is on crowd-pleasers. Amongst the famous (and some not so famous) problems there are some sensational, unexpected key moves, and a lot of surprising and paradoxical continuations. You will pick Amongst the famous up some strategic concepts of problem (and some not so famous) composers along the way, but the emphasis problems there are some is on entertainment rather than instruction. (Often a really surprising move in a sensational, unexpected key solution leads you into exploring why this moves, and a lot of surprising move is the only way to achieve the aim of and paradoxical continuations the problem, and gaining an understanding of problems in this auto-didactic fashion is much the most enjoyable way!) There are also sections on ‘Special Moves’ and ‘Problems Out of the Box’, which The text is very readable (in excellent show how composers have exercised their English), and in studies and longer ingenuity to seek out optimal achievements problems liberally sprinkled with diagrams in showing promotions, e.p. -

White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents

Chess E-Magazine Interactive E-Magazine Volume 3 • Issue 1 January/February 2012 Chess Gambits Chess Gambits The Immortal Game Canada and Chess Anderssen- Vs. -Kieseritzky Bill Wall’s Top 10 Chess software programs C Seraphim Press White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents Editorial~ “My Move” 4 contents Feature~ Chess and Canada 5 Article~ Bill Wall’s Top 10 Software Programs 9 INTERACTIVE CONTENT ________________ Feature~ The Incomparable Kasparov 10 • Click on title in Table of Contents Article~ Chess Variants 17 to move directly to Unorthodox Chess Variations page. • Click on “White Feature~ Proof Games 21 Knight Review” on the top of each page to return to ARTICLE~ The Immortal Game 22 Table of Contents. Anderssen Vrs. Kieseritzky • Click on red type to continue to next page ARTICLE~ News Around the World 24 • Click on ads to go to their websites BOOK REVIEW~ Kasparov on Kasparov Pt. 1 25 • Click on email to Pt.One, 1973-1985 open up email program Feature~ Chess Gambits 26 • Click up URLs to go to websites. ANNOTATED GAME~ Bareev Vs. Kasparov 30 COMMENTARY~ “Ask Bill” 31 White Knight Review January/February 2012 White Knight Review January/February 2012 Feature My Move Editorial - Jerry Wall [email protected] Well it has been over a year now since we started this publication. It is not easy putting together a 32 page magazine on chess White Knight every couple of months but it certainly has been rewarding (maybe not so Review much financially but then that really never was Chess E-Magazine the goal). -

Games Ancient and Oriental and How to Play Them, Being the Games Of

CO CD CO GAMES ANCIENT AND ORIENTAL AND HOW TO PLAY THEM. BEING THE GAMES OF THE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS THE HIERA GRAMME OF THE GREEKS, THE LUDUS LATKUNCULOKUM OF THE ROMANS AND THE ORIENTAL GAMES OF CHESS, DRAUGHTS, BACKGAMMON AND MAGIC SQUAEES. EDWARD FALKENER. LONDON: LONGMANS, GEEEN AND Co. AND NEW YORK: 15, EAST 16"' STREET. 1892. All rights referred. CONTENTS. I. INTRODUCTION. PAGE, II. THE GAMES OF THE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS. 9 Dr. Birch's Researches on the games of Ancient Egypt III. Queen Hatasu's Draught-board and men, now in the British Museum 22 IV. The of or the of afterwards game Tau, game Robbers ; played and called by the same name, Ludus Latrunculorum, by the Romans - - 37 V. The of Senat still the modern and game ; played by Egyptians, called by them Seega 63 VI. The of Han The of the Bowl 83 game ; game VII. The of the Sacred the Hiera of the Greeks 91 game Way ; Gramme VIII. Tlie game of Atep; still played by Italians, and by them called Mora - 103 CHESS. IX. Chess Notation A new system of - - 116 X. Chaturanga. Indian Chess - 119 Alberuni's description of - 139 XI. Chinese Chess - - - 143 XII. Japanese Chess - - 155 XIII. Burmese Chess - - 177 XIV. Siamese Chess - 191 XV. Turkish Chess - 196 XVI. Tamerlane's Chess - - 197 XVII. Game of the Maharajah and the Sepoys - - 217 XVIII. Double Chess - 225 XIX. Chess Problems - - 229 DRAUGHTS. XX. Draughts .... 235 XX [. Polish Draughts - 236 XXI f. Turkish Draughts ..... 037 XXIII. }\'ci-K'i and Go . The Chinese and Japanese game of Enclosing 239 v. -

Prusaprinters

Chinese Chess - Travel Size 3D MODEL ONLY Makerwiz VIEW IN BROWSER updated 6. 2. 2021 | published 6. 2. 2021 Summary This is a full set of Chinese Chess suitable for travelling. We shrunk down the original design to 60% and added a new lid with "Chinese Chess" in traditional Chinese characters. We also added a new chess board graphics file suitable for printing on paper or laser etching/cutting onto wood. Enjoy! Here is a brief intro about Chinese Chess from Wikipedia: 8C 68 "Xiangqi (Chinese: 61 CB ; pinyin: xiàngqí), also called Chinese chess, is a strategy board game for two players. It is one of the most popular board games in China, and is in the same family as Western (or international) chess, chaturanga, shogi, Indian chess and janggi. Besides China and areas with significant ethnic Chinese communities, xiangqi (cờ tướng) is also a popular pastime in Vietnam. The game represents a battle between two armies, with the object of capturing the enemy's general (king). Distinctive features of xiangqi include the cannon (pao), which must jump to capture; a rule prohibiting the generals from facing each other directly; areas on the board called the river and palace, which restrict the movement of some pieces (but enhance that of others); and placement of the pieces on the intersections of the board lines, rather than within the squares." Toys & Games > Other Toys & Games games chess Unassociated tags: Chinese Chess Category: Chess F3 Model Files (.stl, .3mf, .obj, .amf) 3D DOWNLOAD ALL FILES chinese_chess_box_base.stl 15.7 KB F3 3D updated 25. -

53Rd WORLD CONGRESS of CHESS COMPOSITION Crete, Greece, 16-23 October 2010

53rd WORLD CONGRESS OF CHESS COMPOSITION Crete, Greece, 16-23 October 2010 53rd World Congress of Chess Composition 34th World Chess Solving Championship Crete, Greece, 16–23 October 2010 Congress Programme Sat 16.10 Sun 17.10 Mon 18.10 Tue 19.10 Wed 20.10 Thu 21.10 Fri 22.10 Sat 23.10 ICCU Open WCSC WCSC Excursion Registration Closing Morning Solving 1st day 2nd day and Free time Session 09.30 09.30 09.30 free time 09.30 ICCU ICCU ICCU ICCU Opening Sub- Prize Giving Afternoon Session Session Elections Session committees 14.00 15.00 15.00 17.00 Arrival 14.00 Departure Captains' meeting Open Quick Open 18.00 Solving Solving Closing Lectures Fairy Evening "Machine Show Banquet 20.30 Solving Quick Gun" 21.00 19.30 20.30 Composing 21.00 20.30 WCCC 2010 website: http://www.chessfed.gr/wccc2010 CONGRESS PARTICIPANTS Ilham Aliev Azerbaijan Stephen Rothwell Germany Araz Almammadov Azerbaijan Rainer Staudte Germany Ramil Javadov Azerbaijan Axel Steinbrink Germany Agshin Masimov Azerbaijan Boris Tummes Germany Lutfiyar Rustamov Azerbaijan Arno Zude Germany Aleksandr Bulavka Belarus Paul Bancroft Great Britain Liubou Sihnevich Belarus Fiona Crow Great Britain Mikalai Sihnevich Belarus Stewart Crow Great Britain Viktor Zaitsev Belarus David Friedgood Great Britain Eddy van Beers Belgium Isabel Hardie Great Britain Marcel van Herck Belgium Sally Lewis Great Britain Andy Ooms Belgium Tony Lewis Great Britain Luc Palmans Belgium Michael McDowell Great Britain Ward Stoffelen Belgium Colin McNab Great Britain Fadil Abdurahmanović Bosnia-Hercegovina Jonathan -

A Semiotic Analysis on Signs of the English Chess Game

1 A Semiotic Analysis on Signs of the English Chess Game M. I. Andi Purnomo, Drs. Wisasongko, M.A., Hat Pujiati, S.S., M.A. English Department, Faculty of Letter, Jember University Jln. Kalimantan 37, Jember 68121 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This thesis discusses about English Chess Game through Roland Barthes's Myth. In this thesis, I use documentary technique as method of analysis. The analysis is done by the observation of the rules, colors, and images of the English chess game. In addition, chessman and chess formation are analyzed using syntagmatic and paradigmatic relation theory to explore the correlation between symbols of the English chess game with the existence of Christian in the middle age of England. The result of this thesis shows the relation of English chess game with the history of England in the middle age where Christian ideology influences the social, military, and government political life of the English empire. Keywords: chessman, chess piece, bishops, king, knights, pawns, queen, rooks. Introduction Then, the game spread into Europe. Around 1200, the game was established in Britain and the name of “Chess” begins Game is an activity that is done by people for some (Shenk, 2006:51). It means chess spread to English during purposes. Some people use the game as a medium of the Middle Ages. The Middle Age of English begins around interaction with other people. Others use the game as the 1066 – 1485 (www.middle-ages.org.uk). At that time, the activity of spending leisure time. Others use the game as the Christian dominated the whole empire and automatically the major activity for professional. -

Mutant Standard PUA Encoding Reference 0.3.1 (October 2018)

Mutant Standard PUA Encoding Reference 0.3.1 (October 2018) Mutant Standard’s PUA codepoints start at block 16 in Plane 10 Codepoint that Codepoint that New codepoint has existed has been given (SPUA-B) - U+1016xx, and will continue into the next blocks (1017xx, This document is licensed under a Creative Commons before this wording changes version this version 1018xx, etc.) if necessary. Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Every Mutant Standard PUA encoding automatically assumes full- The data contained this document (ie. encodings, emoji descriptions) however, can be used in whatever way you colour emoji representations, so Visibility Selector 16 (U+FE0F) is like. not appropriate or necessary for any of these. Comments 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F Shared CMs 1 1016 0 Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier R1 (dark red) R2 (red) R3 (light red) D1 (dark red- D2 (red-orange) D3 (light red- O1 (dark O2 (orange) O3 (light Y1 (dark yellow) Y2 (yellow) Y3 (light L1 (dark lime) L2 (lime) L3 (light lime) G1 (dark green) orange) orange) orange) orange) yellow) Shared CMs 2 1016 1 Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier Color Modifier G2 (green) G3 (light green) T1 (dark teal) T2 (teal) -

The Oldest Books on Modern Chess

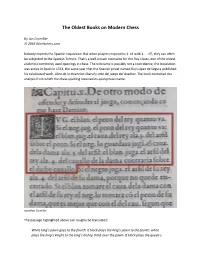

The Oldest Books on Modern Chess By Jon Crumiller © 2016 Worldchess.com Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition. But when players respond to 1. e4 with 1. … e5, they can often be subjected to the Spanish Torture. That’s a well-known nickname for the Ruy López, one of the oldest and most commonly used openings in chess. The nickname is possibly not a coincidence; the Inquisition was active in Spain in 1561, the same year that the Spanish priest named Ruy López de Segura published his celebrated work, Libro de la Invencion liberal y Arte del juego del Axedrez. The book contained the analysis from which the chess opening received its eponymous name. Jonathan Crumiller The passage highlighted above can roughly be translated: White king’s pawn goes to the fourth. If black plays the king’s pawn to the fourth: white plays the king’s knight to the king’s bishop third, over the pawn. If black plays the queen’s knight to queen’s bishop third: white plays the king’s bishop to the fourth square of the contrary queen’s knight, opposed to that knight. Or in our modern chess language: 1. e4, e5 2. Nf3, Nc6 3. Bb5. Jonathan Crumiller On the right is how the Ruy López opening would have looked four centuries ago with a standard chess set and board in Spain. This Spanish chess set is one of my oldest complete sets (along with a companion wooden set of the same era). Jonathan Crumiller Here is the Ruy López as seen with that companion set displayed on a Spanish chessboard, also from the 1600’s. -

Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25

Title: Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25 Introduction The UCS contains symbols for the game of chess in the Miscellaneous Symbols block. These are used in figurine notation, a common variation on algebraic notation in which pieces are represented in running text using the same symbols as are found in diagrams. While the symbols already encoded in Unicode are sufficient for use in the orthodox game, they are insufficient for many chess problems and variant games, which make use of extended sets. 1. Fairy chess problems The presentation of chess positions as puzzles to be solved predates the existence of the modern game, dating back to the mansūbāt composed for shatranj, the Muslim predecessor of chess. In modern chess problems, a position is provided along with a stipulation such as “white to move and mate in two”, and the solver is tasked with finding a move (called a “key”) that satisfies the stipulation regardless of a hypothetical opposing player’s moves in response. These solutions are given in the same notation as lines of play in over-the-board games: typically algebraic notation, using abbreviations for the names of pieces, or figurine algebraic notation. Problem composers have not limited themselves to the materials of the conventional game, but have experimented with different board sizes and geometries, altered rules, goals other than checkmate, and different pieces. Problems that diverge from the standard game comprise a genre called “fairy chess”. Thomas Rayner Dawson, known as the “father of fairy chess”, pop- ularized the genre in the early 20th century.