Play Chess with Paul Morphy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computer Analysis of World Chess Champions 65

Computer Analysis of World Chess Champions 65 COMPUTER ANALYSIS OF WORLD CHESS CHAMPIONS1 Matej Guid2 and Ivan Bratko2 Ljubljana, Slovenia ABSTRACT Who is the best chess player of all time? Chess players are often interested in this question that has never been answered authoritatively, because it requires a comparison between chess players of different eras who never met across the board. In this contribution, we attempt to make such a comparison. It is based on the evaluation of the games played by the World Chess Champions in their championship matches. The evaluation is performed by the chess-playing program CRAFTY. For this purpose we slightly adapted CRAFTY. Our analysis takes into account the differences in players' styles to compensate the fact that calm positional players in their typical games have less chance to commit gross tactical errors than aggressive tactical players. Therefore, we designed a method to assess the difculty of positions. Some of the results of this computer analysis might be quite surprising. Overall, the results can be nicely interpreted by a chess expert. 1. INTRODUCTION Who is the best chess player of all time? This is a frequently posed and interesting question, to which there is no well founded, objective answer, because it requires a comparison between chess players of different eras who never met across the board. With the emergence of high-quality chess programs a possibility of such an objective comparison arises. However, so far computers were mostly used as a tool for statistical analysis of the players' results. Such statistical analyses often do neither reect the true strengths of the players, nor do they reect their quality of play. -

The Lewis Chessmen on a Fantasy Iceland

THE LEWIS CHESSMEN ON A FANTASY ICELAND Morten Lilleøren, November 2011 In 2010, engineer Gudmundur Thorarinsson, helped in some undefined capacity by his public relations specialist Einar Einarsson, published the seldom-visited view that the Lewis pieces were made in Iceland. The revised version of this article, Are the Isle of Lewis Chessmen Icelandic?, as well as his subsequent publications on this topic, may be found at his website: http://leit.is/lewis/. Thorarinsson’s view was addressed in an article by Dylan Loeb McClain of the New York Times, in his somewhat cryptically entitled, Reopening History of Storied Norse Chessmen (http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/09/arts/09lewis.html). Their notion of an Icelandic origin for the Lewis pieces was given substantial promotion by Thorarinsson and Einarsson at those conferences and symposia they could attend. The idiosyncratic idea was not entirely ignored in academic and specialist circles as well. I entered this discussion because I was shocked at the poor method employed by Thorarinsson in the pursuit of support for his theory. Accordingly, I published a riposte to his initial article in May, 2011. I entitled this first essay of mine, The Lewis Chessmen were never anywhere near Iceland, and published it on Chess Café (http://www.chesscafe.com/text/skittles399.pdf). Thorarinsson then published a counter to my questions. Continuing to center his argument on a series of circumstantially-derived and –supported points, he went on to state that, “On behalf of Norway, I am thoroughly disappointed…[and moreover] I meant only to participate in literate discussions and studies” (op. -

PAUL MORPHY Drawn

PRICE FIVE CENTS: : VOLUME 301. CEDAB EAPIDS,JOWA, SATURDAY, DECEMBER 29, 1900-12 PAGES-PAGES 9 TO 12. 1 -creditors can force their debtor' into. •3 SSI, and admittedly the .-best player to Paris and remained about eighteen ver chessmen was taken by Walter Denegre, acting for . tho Manhattan, •the court andi have an equal'settle- 'In Europe. Tn'-addition to the match months. , ' ~~- 1 ment for their accounts per ratio. games, Morphy and Anderssen played Durhig- the ten years following his Chess club of New York, price $.l.r,50: BANKRUPTCY and the silver -wreath .sold for $250, This is the involuntary act and it-;li THE LIFE OF six informal games, of which the return from Europe .in .ISM Morphy's considered by lawyers and- judges a* also bouffht by Mr. Samory. : Prussian master scored only one. The practice ot chess was limited to cas- 1 a whole just and equitable. • informal and match fiumes made a ual.games with intimate friends, chief- An engaging pastime oil chess wrlt- : sra and critics of. late years has:.been "Now comes that -portion, which B total of seventeen games played hy •ly with Charles A. -Murlan ot New COURT BUSY so generally abused, the sectlon"of that o" comparing the laf.ter-day mas- these masters, of which Morphy won Orleans and Arnons .de Riviere of which so many take advantage^-to- twelve, Anderssen throe, and two-were Paris, It Is thought,tiie total number ters with Morphy, but so far" the most flatteri-ng; comparisons have nev- ward- off the host or honest-creditors; PAUL MORPHY drawn. -

Top 10 Checkmate Pa Erns

GM Miguel Illescas and the Internet Chess Club present: Top 10 Checkmate Pa=erns GM Miguel Illescas doesn't need a presentation, but we're talking about one of the most influential chess players in the last decades, especially in Spain, just to put things in the right perspective. Miguel, so far, has won the Spanish national championship of 1995, 1998, 1999, 2001, 2004, 2005, 2007, and 2010. In team competitions, he has represented his country at many Olympiads, from 1986 onwards, and won an individual bronze medal at Turin in 2006. Miguel won international tournaments too, such as Las Palmas 1987 and 1988, Oviedo 1991, Pamplona 1991/92, 2nd at Leon 1992 (after Boris Gulko), 3rd at Chalkidiki 1992 (after Vladimir Kramnik and Joel Lautier), Lisbon Zonal 1993, and 2nd at Wijk aan Zee 1993 (after Anatoly Karpov). He kept winning during the latter part of the nineties, including Linares (MEX) 1994, Linares (ESP) Zonal 1995, Madrid 1996, and Pamplona 1997/98. Some Palmares! The ultimate goal of a chess player is to checkmate the opponent. We know that – especially at the higher level – it's rare to see someone get checkmated over the board, but when it happens, there is a sense of fulfillment that only a checkmate can give. To learn how to checkmate an opponent is not an easy task, though. Checkmating is probably the only phase of the game that can be associated with mathematics. Maths and checkmating have one crucial thing in common: patterns! GM Miguel is not going to show us a long list of checkmate examples: the series intends to teach patterns. -

A Semiotic Analysis on Signs of the English Chess Game

1 A Semiotic Analysis on Signs of the English Chess Game M. I. Andi Purnomo, Drs. Wisasongko, M.A., Hat Pujiati, S.S., M.A. English Department, Faculty of Letter, Jember University Jln. Kalimantan 37, Jember 68121 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This thesis discusses about English Chess Game through Roland Barthes's Myth. In this thesis, I use documentary technique as method of analysis. The analysis is done by the observation of the rules, colors, and images of the English chess game. In addition, chessman and chess formation are analyzed using syntagmatic and paradigmatic relation theory to explore the correlation between symbols of the English chess game with the existence of Christian in the middle age of England. The result of this thesis shows the relation of English chess game with the history of England in the middle age where Christian ideology influences the social, military, and government political life of the English empire. Keywords: chessman, chess piece, bishops, king, knights, pawns, queen, rooks. Introduction Then, the game spread into Europe. Around 1200, the game was established in Britain and the name of “Chess” begins Game is an activity that is done by people for some (Shenk, 2006:51). It means chess spread to English during purposes. Some people use the game as a medium of the Middle Ages. The Middle Age of English begins around interaction with other people. Others use the game as the 1066 – 1485 (www.middle-ages.org.uk). At that time, the activity of spending leisure time. Others use the game as the Christian dominated the whole empire and automatically the major activity for professional. -

UIL Text 111212

UIL Chess Puzzle Solvin g— Fall/Winter District 2016-2017 —Grades 4 and 5 IMPORTANT INSTRUCTIONS: [Test-administrators, please read text in this box aloud.] This is the UIL Chess Puzzle Solving Fall/Winter District Test for grades four and five. There are 20 questions on this test. You have 30 minutes to complete it. All questions are multiple choice. Use the answer sheet to mark your answers. Multiple choice answers pur - posely do not indicate check, checkmate, or e.p. symbols. You will be awarded one point for each correct answer. No deductions will be made for incorrect answers on this test. Finishing early is not rewarded, even to break ties. So use all of your time. Some of the questions may be hard, but all of the puzzles are interesting! Good luck and have fun! If you don’t already know chess notation, reading and referring to the section below on this page will help you. How to read and answer questions on this test Piece Names Each chessman can • To answer the questions on this test, you’ll also be represented need to know how to read chess moves. It’s by a symbol, except for the pawn. simple to do. (Figurine Notation) K King Q • Every square on the board has an “address” Queen R made up of a letter and a number. Rook B Bishop N Knight Pawn a-h (We write the file it’s on.) • To make them easy to read, the questions on this test use the figurine piece symbols on the right, above. -

More About Checkmate

MORE ABOUT CHECKMATE The Queen is the best piece of all for getting checkmate because it is so powerful and controls so many squares on the board. There are very many ways of getting CHECKMATE with a Queen. Let's have a look at some of them, and also some STALEMATE positions you must learn to avoid. You've already seen how a Rook can get CHECKMATE XABCDEFGHY with the help of a King. Put the Black King on the side of the 8-+k+-wQ-+( 7+-+-+-+-' board, the White King two squares away towards the 6-+K+-+-+& middle, and a Rook or a Queen on any safe square on the 5+-+-+-+-% same side of the board as the King will give CHECKMATE. 4-+-+-+-+$ In the first diagram the White Queen checks the Black King 3+-+-+-+-# while the White King, two squares away, stops the Black 2-+-+-+-+" King from escaping to b7, c7 or d7. If you move the Black 1+-+-+-+-! King to d8 it's still CHECKMATE: the Queen stops the Black xabcdefghy King moving to e7. But if you move the Black King to b8 is CHECKMATE! that CHECKMATE? No: the King can escape to a7. We call this sort of CHECKMATE the GUILLOTINE. The Queen comes down like a knife to chop off the Black King's head. But there's another sort of CHECKMATE that you can ABCDEFGH do with a King and Queen. We call this one the KISS OF 8-+k+-+-+( DEATH. Put the Black King on the side of the board, 7+-wQ-+-+-' the White Queen on the next square towards the middle 6-+K+-+-+& and the White King where it defends the Queen and you 5+-+-+-+-% 4-+-+-+-+$ get something like our next diagram. -

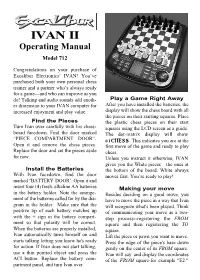

IVAN II Operating Manual Model 712

IVAN II Operating Manual Model 712 Congratulations on your purchase of Excalibur Electronics’ IVAN! You’ve purchased both your own personal chess trainer and a partner who’s always ready for a game—and who can improve as you do! Talking and audio sounds add anoth- Play a Game Right Away er dimension to your IVAN computer for After you have installed the batteries, the increased enjoyment and play value. display will show the chess board with all the pieces on their starting squares. Place Find the Pieces the plastic chess pieces on their start Turn Ivan over carefully with his chess- squares using the LCD screen as a guide. board facedown. Find the door marked The dot-matrix display will show “PIECE COMPARTMENT DOOR”. 01CHESS. This indicates you are at the Open it and remove the chess pieces. first move of the game and ready to play Replace the door and set the pieces aside chess. for now. Unless you instruct it otherwise, IVAN gives you the White pieces—the ones at Install the Batteries the bottom of the board. White always With Ivan facedown, find the door moves first. You’re ready to play! marked “BATTERY DOOR’. Open it and insert four (4) fresh, alkaline AA batteries Making your move in the battery holder. Note the arrange- Besides deciding on a good move, you ment of the batteries called for by the dia- have to move the piece in a way that Ivan gram in the holder. Make sure that the will recognize what's been played. Think positive tip of each battery matches up of communicating your move as a two- with the + sign in the battery compart- step process--registering the FROM ment so that polarity will be correct. -

CHESS REVIEW but We Can Give a Bit More in a Few 250 West 57Th St Reet , New York 19, N

JULY 1957 CIRCUS TIME (See page 196 ) 50 CENTS ~ scription Rate ONE YEAR $5.50 From the "Amenities and Background of Chess-Play" by Ewart Napier ECHOES FROM THE PAST From Leipsic Con9ress, 1894 An Exhibition Game Almos t formidable opponent was P aul Lipk e in his pr ime, original a nd pi ercing This instruc tive game displays these a nd effective , Quite typica l of 'h is temper classical rivals in holiUay mood, ex is the ",lid Knigh t foray a t 8. Of COU I'se, ploring a dangerous Queen sacrifice. the meek thil'd move of Black des e r\" e~ Played at Augsburg, Germany, i n 1900, m uss ing up ; Pillsbury adopted t he at thirty moves an hOlll" . Tch igorin move, 3 . N- B3. F A L K BEE R COU NT E R GAM BIT Q U EE N' S PAW N GA ME" 0 1'. E. Lasker H. N . Pi llsbury p . Li pke E. Sch iffers ,Vhite Black W hite Black 1 P_K4 P-K4 9 8-'12 B_ KB4 P_Q4 6 P_ KB4 2 P_KB4 P-Q4 10 0-0- 0 B,N 1 P-Q4 8-K2 Mate announred in eight. 2 P- K3 KN_ B3 7 N_ R3 3 P xQP P-K5 11 Q- N4 P_ K B4 0 - 0 8 N_N 5 K N_B3 12 Q-N3 N-Q2 3 B-Q3 P- K 3? P-K R3 4 Q N- B3 p,p 5 Q_ K2 B-Q3 13 8-83 N-B3 4 N-Q2 P-B4 9 P-K R4 6 P_Q3 0-0 14 N-R3 N_ N5 From Leipsic Con9ress. -

Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25

Title: Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25 Introduction The UCS contains symbols for the game of chess in the Miscellaneous Symbols block. These are used in figurine notation, a common variation on algebraic notation in which pieces are represented in running text using the same symbols as are found in diagrams. While the symbols already encoded in Unicode are sufficient for use in the orthodox game, they are insufficient for many chess problems and variant games, which make use of extended sets. 1. Fairy chess problems The presentation of chess positions as puzzles to be solved predates the existence of the modern game, dating back to the mansūbāt composed for shatranj, the Muslim predecessor of chess. In modern chess problems, a position is provided along with a stipulation such as “white to move and mate in two”, and the solver is tasked with finding a move (called a “key”) that satisfies the stipulation regardless of a hypothetical opposing player’s moves in response. These solutions are given in the same notation as lines of play in over-the-board games: typically algebraic notation, using abbreviations for the names of pieces, or figurine algebraic notation. Problem composers have not limited themselves to the materials of the conventional game, but have experimented with different board sizes and geometries, altered rules, goals other than checkmate, and different pieces. Problems that diverge from the standard game comprise a genre called “fairy chess”. Thomas Rayner Dawson, known as the “father of fairy chess”, pop- ularized the genre in the early 20th century. -

Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames

Games of No Chance MSRI Publications Volume 29, 1996 Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames LEWIS STILLER Abstract. This article has three chief aims: (1) To show the wide utility of multilinear algebraic formalism for high-performance computing. (2) To describe an application of this formalism in the analysis of chess endgames, and results obtained thereby that would have been impossible to compute using earlier techniques, including a win requiring a record 243 moves. (3) To contribute to the study of the history of chess endgames, by focusing on the work of Friedrich Amelung (in particular his apparently lost analysis of certain six-piece endgames) and that of Theodor Molien, one of the founders of modern group representation theory and the first person to have systematically numerically analyzed a pawnless endgame. 1. Introduction Parallel and vector architectures can achieve high peak bandwidth, but it can be difficult for the programmer to design algorithms that exploit this bandwidth efficiently. Application performance can depend heavily on unique architecture features that complicate the design of portable code [Szymanski et al. 1994; Stone 1993]. The work reported here is part of a project to explore the extent to which the techniques of multilinear algebra can be used to simplify the design of high- performance parallel and vector algorithms [Johnson et al. 1991]. The approach is this: Define a set of fixed, structured matrices that encode architectural primitives • of the machine, in the sense that left-multiplication of a vector by this matrix is efficient on the target architecture. Formulate the application problem as a matrix multiplication. -

Chess-Training-Guide.Pdf

Q Chess Training Guide K for Teachers and Parents Created by Grandmaster Susan Polgar U.S. Chess Hall of Fame Inductee President and Founder of the Susan Polgar Foundation Director of SPICE (Susan Polgar Institute for Chess Excellence) at Webster University FIDE Senior Chess Trainer 2006 Women’s World Chess Cup Champion Winner of 4 Women’s World Chess Championships The only World Champion in history to win the Triple-Crown (Blitz, Rapid and Classical) 12 Olympic Medals (5 Gold, 4 Silver, 3 Bronze) 3-time US Open Blitz Champion #1 ranked woman player in the United States Ranked #1 in the world at age 15 and in the top 3 for about 25 consecutive years 1st woman in history to qualify for the Men’s World Championship 1st woman in history to earn the Grandmaster title 1st woman in history to coach a Men's Division I team to 7 consecutive Final Four Championships 1st woman in history to coach the #1 ranked Men's Division I team in the nation pnlrqk KQRLNP Get Smart! Play Chess! www.ChessDailyNews.com www.twitter.com/SusanPolgar www.facebook.com/SusanPolgarChess www.instagram.com/SusanPolgarChess www.SusanPolgar.com www.SusanPolgarFoundation.org SPF Chess Training Program for Teachers © Page 1 7/2/2019 Lesson 1 Lesson goals: Excite kids about the fun game of chess Relate the cool history of chess Incorporate chess with education: Learning about India and Persia Incorporate chess with education: Learning about the chess board and its coordinates Who invented chess and why? Talk about India / Persia – connects to Geography Tell the story of “seed”.