A Chronology of Three Months of Unrest in Singapore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Singapore's Chinese-Speaking and Their Perspectives on Merger

Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies, Volume 5, 2011-12 南方華裔研究雜志, 第五卷, 2011-12 “Flesh and Bone Reunite as One Body”: Singapore’s Chinese- speaking and their Perspectives on Merger ©2012 Thum Ping Tjin* Abstract Singapore’s Chinese speakers played the determining role in Singapore’s merger with the Federation. Yet the historiography is silent on their perspectives, values, and assumptions. Using contemporary Chinese- language sources, this article argues that in approaching merger, the Chinese were chiefly concerned with livelihoods, education, and citizenship rights; saw themselves as deserving of an equal place in Malaya; conceived of a new, distinctive, multiethnic Malayan identity; and rejected communist ideology. Meanwhile, the leaders of UMNO were intent on preserving their electoral dominance and the special position of Malays in the Federation. Finally, the leaders of the PAP were desperate to retain power and needed the Federation to remove their political opponents. The interaction of these three factors explains the shape, structure, and timing of merger. This article also sheds light on the ambiguity inherent in the transfer of power and the difficulties of national identity formation in a multiethnic state. Keywords: Chinese-language politics in Singapore; History of Malaya; the merger of Singapore and the Federation of Malaya; Decolonisation Introduction Singapore’s merger with the Federation of Malaya is one of the most pivotal events in the country’s history. This process was determined by the ballot box – two general elections, two by-elections, and a referendum on merger in four years. The centrality of the vote to this process meant that Singapore’s Chinese-speaking1 residents, as the vast majority of the colony’s residents, played the determining role. -

Folio No: DM.036 Folio Title: Correspondence (Official) With

Folio No: DM.036 Folio Title: Correspondence (Official) with Chief Minister Content Description: Correspondence with Lim Yew Hock re: official matters, re-opening of Constitutional Talks and views of Australian interference in Merdeka process. Includes letter to GE Boggars on Chia Thye Poh and correspondence, as Chairman of Workers' Party, with Tunku Abdul Rahman re: merger of Singapore with Malaya. Also included is a typescript of discussion with Chou En-lai on Chinese citizenship and notes on Lee Kuan Yew's stand on several issues ITEM DOCUMENT DIGITIZATION ACCESS DOCUMENT CONTENT NO DATE STATUS STATUS Copy of notes on Lee Kuan Yew's views and statements on nationalisation, citizenship, elections, democracy, DM.036.001 Undated Digitized Open education and multi-lingualism [extracted from Legislative Assembly records] from 1955 - 1959 Letter to the Chief Minister re: Radio Malaya broadcast DM.036.002 13/6/1956 Digitized Open of [horse] race results Request to the Chief Minister to follow up on pensions DM.036.003 18/6/1956 Digitized Open under the civil liabilities scheme DM.036.004 20/6/1956 Reply from Lim Yew Hock re: action taken re: DM.36.3 Digitized Open Letter to the Chief Minister re: view of interference DM.036.005 20/6/1956 from Australian government in independence Digitized Open movement, offering solution DM.036.006 25/6/1956 From Chief Minister re: S Araneta's identity Digitized Open Letter to Chief Minister's Office enclosing from The Old DM.036.007 2/11/1956 Digitized Open Fire Engine Shop, USA Letter to Gerald de Cruz, -

Transcript of the Question and Answer Session at a Public Forum Organised by the University of Singapore Students' Union on Mo

1 TRANSCRIPT OF THE QUESTION AND ANSWER SESSION AT A PUBLIC FORUM ORGANISED BY THE UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE STUDENTS’ UNION ON MONDAY THE 27TH AUGUST, 1962. QUESTION BY JOSEPH LYNUS: After careful scrutiny we have been convinced that the change from nationality to citizenship has just been a change in nomenclature. You, Mr. Lee, earlier maintained that there was no difference between the meaning of these terms. Since you now use the term “citizenship” as opposed to “nationality”, we see an inconsistency in your terms. Please explain yourself. Prime Minister: I am sorry that Mr. Lynus believes that I have been inconsistent. I have always maintained that the State Advocate-General of Singapore was absolutely right when he said there was in law no distinction between the concept of a common nationality or a common citizenship. However, apart from what the law was, we had to take into consideration the political propaganda on the ground. And I LKY/1962/LKY0827B.doc 2 say this, quite simply, my enemies took a dangerous line when they had insisted that citizenship was different from nationality and they wanted citizenship. Well, you remember Mr. Marshall, he is a man not unlearned in the law, he came before this very same gathering two months ago, and he said this: “We do not quarrel about proportional representation. “We do not quarrel about with their insistence that Singapore politicians should vote or stand for election in the Federation. So we say, ‘we accept it Tengku, but let us have a common citizenship and let us have a common constitutional disability that no Federation citizen can stand or vote in Singapore. -

An Analysis of the Underlying Factors That Affected Malaysia-Singapore Relations During the Mahathir Era: Discords and Continuity

An Analysis of the Underlying Factors That Affected Malaysia-Singapore Relations During the Mahathir Era: Discords and Continuity Rusdi Omar Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Discipline of Politics and International Studies School of History and Politics Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences The University of Adelaide May 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE PAGE TABLE OF CONTENTS i ABSTRACT v DECLARATION vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vii ABBREVIATIONS/ACRONYMS ix GLOSSARY xii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1. Introductory Background 1 1.2. Statement of the Problem 3 1.3. Research Aims and Objectives 5 1.4. Scope and Limitation 6 1.5. Literature Review 7 1.6. Theoretical/ Conceptual Framework 17 1.7. Research Methodology 25 1.8. Significance of Study 26 1.9. Thesis Organization 27 2 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF MALAYSIA-SINGAPORE RELATIONS 30 2.1. Introduction 30 2.2. The Historical Background of Malaysia 32 2.3. The Historical Background of Singapore 34 2.4. The Period of British Colonial Rule 38 i 2.4.1. Malayan Union 40 2.4.2. Federation of Malaya 43 2.4.3. Independence for Malaya 45 2.4.4. Autonomy for Singapore 48 2.5. Singapore’s Inclusion in the Malaysian Federation (1963-1965) 51 2.6. The Period after Singapore’s Separation from Malaysia 60 2.6.1. Tunku Abdul Rahman’s Era 63 2.6.2 Tun Abdul Razak’s Era 68 2.6.3. Tun Hussein Onn’s Era 76 2.7. Conclusion 81 3 CONTENTIOUS ISSUES IN MALAYSIA-SINGAPORE RELATIONS 83 3.1. Introduction to the Issues Affecting Relations Between Malaysia and Singapore 83 3.2. -

DM.029 Folio Title: Labour Front Correspondence Content Description: Party Correspondence and Other Documents, List of Venues for the "Meet the People" Sessions

Folio No: DM.029 Folio Title: Labour Front Correspondence Content Description: Party correspondence and other documents, list of venues for the "meet the People" sessions. Includes extract of a speech by the Chief Minister of Malaya on 20 Feb 1956 and invitation to the various party leaders to an All-Party Rally, arrangements at the airport to send David Marshall off, and anonymous letters. Correspondents include: Keng Ban Ee Er, Richard C.H. Lim, Lim Yew Hock, and S.H. Moffat ITEM DOCUMENT DIGITIZATION ACCESS DOCUMENT CONTENT NO DATE STATUS STATUS Memo from Keng Ban Ee enclosing List of venues for DM.29.001 2/2/1955 Digitized Open "Meet the People Sessions" Letter from Rabbi Harold H Gordon re: meeting up in DM.29.002 12/1/1956 Digitized Open New York Letter from Omar bin Salleh announcing appointment of DM.29.003 16/2/1956 S Devaraj, G Abishigenaden and Madam E Vaithinatha as Digitized Open Organisers of Cairnhill Division Letter from SH Moratt of the Labour Party of Israel, re: DM.29.004 1/2/1956 Digitized Open developments in Israel Letter from S Ramachandra, with views on immigrant and DM.29.005 6/2/1956 other issues, enclosing news clipping from Singapore Digitized Open Standard dated 2 Feb 1955 DM.29.006 9/2/1956 Anonymous letter chiding about "bad language" Digitized Open Letter from EH Koh offering service for the proposed DM.29.007 16/1/1956 Digitized Open Ministry of Labour and Industry DM.29.008 20/2/1956 Follow up letter to DM.29.7 Digitized Open Extract of speech by the Chief Minister of the Federation DM.29.009 21/2/1956 -

Class and Politics in Malaysian and Singaporean Nation Building

CLASS AND POLITICS IN MALAYSIAN AND SINGAPOREAN NATION BUILDING Muhamad Nadzri Mohamed Noor, M.A. Political Science College of Business, Government and Law Flinders University Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2017 Page Left Deliberately Blank. Abstract This study endeavours to deliver an alternative account of the study of nation-building by examining the subject matter eclectically from diverse standpoints, predominantly that of class in Southeast Asia which is profoundly dominated by ‘cultural’ perspectives. Two states in the region, Malaysia and Singapore, have been selected to comprehend and appreciate the nature of nation-building in these territories. The nation-building processes in both of the countries have not only revolved around the national question pertaining to the dynamic relations between the states and the cultural contents of the racial or ethnic communities in Malaysia and Singapore; it is also surrounded, as this thesis contends, by the question of class - particularly the relations between the new capitalist states’ elites (the rulers) and their masses (the ruled). More distinctively this thesis perceives nation-building as a project by political elites for a variety of purposes, including elite entrenchment, class (re)production and regime perpetuation. The project has more to do with ‘class-(re)building’ and ‘subject- building’ rather than ‘nation-building’. Although this thesis does not eliminate the significance of culture in the nation-building process in both countries; it is explicated that cultures were and are heavily employed to suit the ruling class’s purpose. Hence, the cultural dimension shall be used eclectically with other perspectives. -

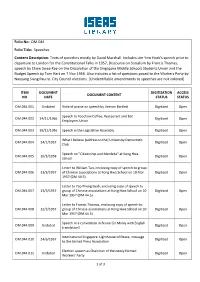

Folio No: DM.044 Folio Title: Speeches Content Description: Texts of Speeches Mostly by David Marshall. Includes Lim Yew Hock'

Folio No: DM.044 Folio Title: Speeches Content Description: Texts of speeches mostly by David Marshall. Includes Lim Yew Hock's speech prior to departure to London for the Constitutional Talks in 1957, Discourse on Socialism by Francis Thomas, speech by Chew Swee Kee on the Dissolution of the Singapore Middle Schools Students Union and the Budget Speech by Tom Hart on 7 Nov 1956. Also includes a list of questions posed to the Workers Party by Nanyang Siang Pau re: City Council elections. [Unidentifiable amendments to speeches are not indexed] ITEM DOCUMENT DIGITIZATION ACCESS DOCUMENT CONTENT NO DATE STATUS STATUS DM.044.001 Undated Note of praise on speech by Vernon Bartlett Digitized Open Speech to Foochow Coffee, Restaurant and Bar DM.044.002 14/11/1956 Digitized Open Employees Union DM.044.003 19/11/1956 Speech in the Legislative Assembly Digitized Open What I Believe [address to the] University Democratic DM.044.004 24/1/1957 Digitized Open Club Speech on "Citizenship and Merdeka" at Kong Hwa DM.044.005 10/3/1958 Digitized Open School Letter to William Tan, enclosing copy of speech to group DM.044.006 13/3/1957 of Chinese associations at Kong Hwa School on 10 Mar Digitized Open 1957 (DM.44.5) Letter to Yap Pheng Geck, enclosing copy of speech to DM.044.007 13/3/1957 group of Chinese associations at Kong Hwa School on 10 Digitized Open Mar 1957 (DM.44.5) Letter to Francis Thomas, enclosing copy of speech to DM.044.008 12/3/1957 group of Chinese associations at Kong Hwa School on 10 Digitized Open Mar 1957 (DM.44.5) Speech at a convention -

The British Intelligence Community in Singapore, 1946-1959: Local

The British intelligence community in Singapore, 1946-1959: Local security, regional coordination and the Cold War in the Far East Alexander Nicholas Shaw Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD The University of Leeds, School of History January 2019 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Alexander Nicholas Shaw to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Alexander Nicholas Shaw in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Acknowledgements I would like to thank all those who have supported me during this project. Firstly, to my funders, the White Rose College of the Arts and Humanities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. Caryn Douglas and Clare Meadley have always been most encouraging and have never stinted in supplying sausage rolls. At Leeds, I am grateful to my supervisors Simon Ball, Adam Cathcart and, prior to his retirement, Martin Thornton. Emma Chippendale and Joanna Phillips have been invaluable guides in navigating the waters of PhD admin. In Durham, I am indebted to Francis Gotto from Palace Green Library and the Oriental Museum’s Craig Barclay and Rachel Barclay. I never expected to end up curating an exhibition of Asian art when I started researching British intelligence, but Rachel and Craig made that happen. -

Singapore.Pdf

Singapore A History ofthe Lion City by Bjorn Schelander with illustrations by AnnHsu Published by the Center for Southeast Asian Studies School of Hawaiian, Asian and Pacific Studies University of Hawai'i 1998 Partially funded by the -U.S. Department of Education Table of Contents PREFACE Chapter One: Early History of Singapore 1 From Temasek to Singapore 2 Early Archeological Evidence 3 The Rise of Malacca 5 The Raffles Years 9 Thomas Stamford Raffles 9 British, Dutch, and Malay Relations 12 Raffles and the Founding of Singapore 14 Farquhar's Administration of Singapore 17 The Return of Raffles 20 The Straits Settlements 22 Consolidation of British Interests in the Malay Peninsula 24 Profits, Piracy, and Pepper 25 Timeline of Important Events 28 Exercises 29 Chapter Two: The Colonial Era 35 Singapore Becomes a Crown Colony 36 Development ofTrade, Transportation, and Communication 36 A Multi-Ethnic Society 40 Syonan: Singapore and World War II 50 Prelude to War 50 Japanese In vasion of the Malay Peninsula 52 Singapore under Japanese Administration 54 Timeline of Important Events 57 Exercises 58 Chapter Three: Independence 63 The Post WarYears 64 The Road to Independence 65 Lee Kuan Yew and the People's Action Party 66 Merger of Malaya and Singapore 68 An Independent Singapore 69 Economy 74 Government 77 International Relations 79 Security 81 Urban Development 82 Education 83 People 84 Looking to the Future 88 Timeline of Important Events 89 Exercises 90 KEY TO EXERCISES: 95 BIBLIOGRAPHY 101 Preface What has allowed Singapore to become one of the most prosperous nations of Asia? In the years leading up to AD 2000, Singapore achieved a standard of living second only to Japan among the countries of Asia. -

Politics, Security and Early Ideas of 'Greater Malaysia', 1945-1961

Archipel Études interdisciplinaires sur le monde insulindien 94 | 2017 Varia Politics, Security and Early Ideas of ‘Greater Malaysia’, 1945-1961 Politique, sécurité et premières idées de ‘Plus Grande Malaisie’, 1945-1961 Joseph M. Fernando and Shanthiah Rajagopal Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/archipel/445 DOI: 10.4000/archipel.445 ISSN: 2104-3655 Publisher Association Archipel Printed version Date of publication: 6 December 2017 Number of pages: 97-119 ISBN: 978-2-910513-78-8 ISSN: 0044-8613 Electronic reference Joseph M. Fernando and Shanthiah Rajagopal, « Politics, Security and Early Ideas of ‘Greater Malaysia’, 1945-1961 », Archipel [Online], 94 | 2017, Online since 06 December 2017, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/archipel/445 ; DOI : 10.4000/archipel.445 Association Archipel JOSEPH M. FERNANDO1 AND SHANTHIAH RAJAGOPAL2 Politics, Security and Early Ideas of ‘Greater Malaysia’, 1945-1961 12The Federation of Malaysia was formed in September 1963 after years of backroom discussions, planning and, inally, very intense and delicate negotiations between late 1961 and 1963. The origins of the federation, however, remain a contentious issue among scholars. The idea of a wider political entity, encompassing the Federation of Malaya, the British-controlled territories of Sarawak, North Borneo, Singapore, and Brunei, was formally announced by Tunku Abdul Rahman, the Prime Minister of the independent Federation of Malaya, at a speech given to the Foreign Correspondents Association of Southeast Asia in Singapore on 27 May 1961. In his speech, Tunku suggested the desirability of a “closer association” of the territories of Malaya, Singapore, North Borneo, Sarawak and Brunei to strengthen political and economic cooperation.3 The announcement was a major departure from the previous position of his Alliance Party government vis-à-vis the merger with 1. -

David Marshall”, Leaders of Singapore (Singapore: Resource Press, 1996), Pp.69-70

Biographical Notes David Saul Marshall (12 March 1908 – 12 December 1995) – Lawyer/politician/diplomat David Saul Marshall was born on 12 March 1908, one of seven children of Saul Nassim and Flora Mashal. His parents were Sephardic Jews, and Marshall was brought up learning Hebrew and according to strict Jewish practices. The family name “Mashal” was anglicised to “Marshall”.1 Marshall studied in several schools including St Andrew’s School and the Raffles Institution.2 He suffered from poor health in his youth and was sent to Switzerland for rehabilitation. There, Marshall studied French, and became intrigued by its literature and the French ideals of liberty, equality and fraternity.3 Subsequently, Marshall was certified as a teacher of French and taught night classes at the YMCA.4 Although his ambition was to study medicine, tight finances made it more practical for Marshall to study law.5 In 1937, Marshall received his Bachelor of Laws degree from the University of London and was called to the English Bar at the Middle Temple.6 The following year, Marshall was called to the Singapore Bar.7 Marshall began his legal career at Aitken and Ong Siang, but left in 1940 for Allen and Gledhill, then the largest law firm in Singapore.8 In the run-up to the Japanese invasion of Singapore, Marshall joined the Straits Settlements Volunteer Force.9 When Singapore fell, Marshall was captured as a prisoner-of-war. He was initially interned in Changi Prison but later sent to work in a labour camp in Hokkaido, Japan.10 In the post-war years, Marshall became involved in various community and civil society groups. -

David Marshall and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Singapore

COVER SHEET This is the author-version of article published as: Trocki, Carl A. (2005) David Marshall and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Singapore. In Chua, Beng Huat and Trocki, Carl A. and Barr, Michael D., Eds. Proceedings Paths Not Taken: Political Pluralism in Postwar Singapore, Asia Research Institue, National University of Singapore. Accessed from http://eprints.qut.edu.au Copyright 2005 the author D R A F T DO NOT CITE WITHOUT PERMISSION OF THE AUTHOR David Marshall and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Singapore By Carl A. Trocki ©2005 A paper to be presented to the “Paths Not Taken” Symposium, Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, Singapore, 14-15 July 2005. “David Marshall and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Singapore”1 Carl A. Trocki Anyone familiar with the hapless opposition figures that presented themselves to Singapore in the mid-1980s would believe that a viable and critical tradition of parliamentary and public opposition had never existed in Singapore. Indeed, it is true that the generation which was then coming of age in Singapore had not experienced a time when it was possible to voice real opposition. Only people of their parents’ generation could have remembered a time when it was possible for an opponent of the People’s Action Party (PAP) and then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, to present a cogent alternative view of political life to Singaporeans. There was, for a time at least, some opposition voices that championed the causes of political plurality, the rule of law, administrative transparency, human and civil rights, and the basic principles of democratic government.