Singapore's Chinese-Speaking and Their Perspectives on Merger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Singapore, July 2006

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Singapore, July 2006 COUNTRY PROFILE: SINGAPORE July 2006 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Singapore (English-language name). Also, in other official languages: Republik Singapura (Malay), Xinjiapo Gongheguo― 新加坡共和国 (Chinese), and Cingkappãr Kudiyarasu (Tamil) சி க யரச. Short Form: Singapore. Click to Enlarge Image Term for Citizen(s): Singaporean(s). Capital: Singapore. Major Cities: Singapore is a city-state. The city of Singapore is located on the south-central coast of the island of Singapore, but urbanization has taken over most of the territory of the island. Date of Independence: August 31, 1963, from Britain; August 9, 1965, from the Federation of Malaysia. National Public Holidays: New Year’s Day (January 1); Lunar New Year (movable date in January or February); Hari Raya Haji (Feast of the Sacrifice, movable date in February); Good Friday (movable date in March or April); Labour Day (May 1); Vesak Day (June 2); National Day or Independence Day (August 9); Deepavali (movable date in November); Hari Raya Puasa (end of Ramadan, movable date according to the Islamic lunar calendar); and Christmas (December 25). Flag: Two equal horizontal bands of red (top) and white; a vertical white crescent (closed portion toward the hoist side), partially enclosing five white-point stars arranged in a circle, positioned near the hoist side of the red band. The red band symbolizes universal brotherhood and the equality of men; the white band, purity and virtue. The crescent moon represents Click to Enlarge Image a young nation on the rise, while the five stars stand for the ideals of democracy, peace, progress, justice, and equality. -

Douglas Hyde (1911-1996), Campaigner and Journalist

The University of Manchester Research Douglas Hyde (1911-1996), campaigner and journalist Document Version Accepted author manuscript Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Morgan, K., Gildart, K. (Ed.), & Howell, D. (Ed.) (2010). Douglas Hyde (1911-1996), campaigner and journalist. In Dictionary of Labour Biography vol. XIII (pp. 162-175). Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Published in: Dictionary of Labour Biography vol. XIII Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:24. Sep. 2021 Douglas Hyde (journalist and political activist) Douglas Arnold Hyde was born at Broadwater, Sussex on 8 April 1911. His family moved, first to Guildford, then to Bristol at the start of the First World War, and he was brought up on the edge of Durdham Downs. His father Gerald Hyde (1892-1968) was a master baker forced to take up waged work on the defection of a business partner. -

The War on Terrorism and the Internal Security Act of Singapore

Damien Cheong ____________________________________________________________ Selling Security: The War on Terrorism and the Internal Security Act of Singapore DAMIEN CHEONG Abstract The Internal Security Act (ISA) of Singapore has been transformed from a se- curity law into an effective political instrument of the Singapore government. Although the government's use of the ISA for political purposes elicited negative reactions from the public, it was not prepared to abolish, or make amendments to the Act. In the wake of September 11 and the international campaign against terrorism, the opportunity to (re)legitimize the government's use of the ISA emerged. This paper argues that despite the ISA's seeming importance in the fight against terrorism, the absence of explicit definitions of national security threats, either in the Act itself, or in accompanying legislation, renders the ISA susceptible to political misuse. Keywords: Internal Security Act, War on Terrorism. People's Action Party, Jemaah Islamiyah. Introduction In 2001/2002, the Singapore government arrested and detained several Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) operatives under the Internal Security Act (ISA) for engaging in terrorist activities. It was alleged that the detained operatives were planning to attack local and foreign targets in Singa- pore. The arrests outraged human rights groups, as the operation was reminiscent of the government's crackdown on several alleged Marxist conspirators in1987. Human rights advocates were concerned that the current detainees would be dissuaded from seeking legal counsel and subjected to ill treatment during their period of incarceration (Tang 1989: 4-7; Frank et al. 1991: 5-99). Despite these protests, many Singaporeans expressed their strong support for the government's actions. -

Folio No: DM.036 Folio Title: Correspondence (Official) With

Folio No: DM.036 Folio Title: Correspondence (Official) with Chief Minister Content Description: Correspondence with Lim Yew Hock re: official matters, re-opening of Constitutional Talks and views of Australian interference in Merdeka process. Includes letter to GE Boggars on Chia Thye Poh and correspondence, as Chairman of Workers' Party, with Tunku Abdul Rahman re: merger of Singapore with Malaya. Also included is a typescript of discussion with Chou En-lai on Chinese citizenship and notes on Lee Kuan Yew's stand on several issues ITEM DOCUMENT DIGITIZATION ACCESS DOCUMENT CONTENT NO DATE STATUS STATUS Copy of notes on Lee Kuan Yew's views and statements on nationalisation, citizenship, elections, democracy, DM.036.001 Undated Digitized Open education and multi-lingualism [extracted from Legislative Assembly records] from 1955 - 1959 Letter to the Chief Minister re: Radio Malaya broadcast DM.036.002 13/6/1956 Digitized Open of [horse] race results Request to the Chief Minister to follow up on pensions DM.036.003 18/6/1956 Digitized Open under the civil liabilities scheme DM.036.004 20/6/1956 Reply from Lim Yew Hock re: action taken re: DM.36.3 Digitized Open Letter to the Chief Minister re: view of interference DM.036.005 20/6/1956 from Australian government in independence Digitized Open movement, offering solution DM.036.006 25/6/1956 From Chief Minister re: S Araneta's identity Digitized Open Letter to Chief Minister's Office enclosing from The Old DM.036.007 2/11/1956 Digitized Open Fire Engine Shop, USA Letter to Gerald de Cruz, -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)“ . If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in “sectioning" the material. It is customary tc begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from “ photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Lion City Adventures Secrets of the Heartlandsfor Review Only Join the Lion City Adventuring Club and Take a Journey Back in Time to C

don bos Lion City Adventures secrets of the heartlandsFor Review only Join the Lion City Adventuring Club and take a journey back in time to C see how the fascinating heartlands of Singapore have evolved. o s ecrets of the Each chapter contains a history of the neighbourhood, information about remarkable people and events, colourful illustrations, and a fun activity. You’ll also get to tackle story puzzles and help solve an exciting mystery along the way. s heA ArtL NDS e This is a sequel to the popular children’s book, Lion City Adventures. C rets of the he rets the 8 neighbourhoods feAtured Toa Payoh Yishun Queenstown Tiong Bahru Kampong Bahru Jalan Kayu Marine Parade Punggol A rt LA nds Marshall Cavendish Marshall Cavendish In association with Super Cool Books children’s/singapore ISBN 978-981-4721-16-5 ,!7IJ8B4-hcbbgf! Editions i LLustrAted don bos Co by shAron Lei For Review only lIon City a dventures don bosco Illustrated by VIshnu n rajan L I O N C I T Y ADVENTURING CLUB now clap your hands and repeat this loudly: n For Review only orth, south, east and west! I am happy to do my best! Editor: Melvin Neo Designer: Adithi Shankar Khandadi Illustrator: Vishnu N Rajan © 2015 Don Bosco (Super Cool Books) and Marshall Cavendish International (Asia) Pte Ltd y ou, This book is published by Marshall Cavendish Editions in association with Super Cool Books. Reprinted 2016, 2019 ______________________________ , Published by Marshall Cavendish Editions (write your name here) An imprint of Marshall Cavendish International are hereby invited to join the All rights reserved lion city adventuring club No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval systemor transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, on a delightful adventure without the prior permission of the copyright owner. -

The North Kalimantan Communist Party and the People's Republic Of

The Developing Economies, XLIII-4 (December 2005): 489–513 THE NORTH KALIMANTAN COMMUNIST PARTY AND THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA FUJIO HARA First version received January 2005; final version accepted July 2005 In this article, the author offers a detailed analysis of the history of the North Kalimantan Communist Party (NKCP), a political organization whose foundation date itself has been thus far ambiguous, relying mainly on the party’s own documents. The relation- ships between the Brunei Uprising and the armed struggle in Sarawak are also referred to. Though the Brunei Uprising of 1962 waged by the Partai Rakyat Brunei (People’s Party of Brunei) was soon followed by armed struggle in Sarawak, their relations have so far not been adequately analyzed. The author also examines the decisive roles played by Wen Ming Chyuan, Chairman of the NKCP, and the People’s Republic of China, which supported the NKCP for the entire period following its inauguration. INTRODUCTION PRELIMINARY study of the North Kalimantan Communist Party (NKCP, here- after referred to as “the Party”), an illegal leftist political party based in A Sarawak, was published by this author in 2000 (Hara 2000). However, the study did not rely on the official documents of the Party itself, but instead relied mainly on information provided by third parties such as the Renmin ribao of China and the Zhen xian bao, the newspaper that was the weekly organ of the now defunct Barisan Sosialis of Singapore. Though these were closely connected with the NKCP, many problems still remained unresolved. In this study the author attempts to construct a more precise party history relying mainly on the party’s own information and docu- ments provided by former members during the author’s visit to Sibu in August 2001.1 –––––––––––––––––––––––––– This paper is an outcome of research funded by the Pache Research Subsidy I-A of Nanzan University for the academic year 2000. -

One Party Dominance Survival: the Case of Singapore and Taiwan

One Party Dominance Survival: The Case of Singapore and Taiwan DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lan Hu Graduate Program in Political Science The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Professor R. William Liddle Professor Jeremy Wallace Professor Marcus Kurtz Copyrighted by Lan Hu 2011 Abstract Can a one-party-dominant authoritarian regime survive in a modernized society? Why is it that some survive while others fail? Singapore and Taiwan provide comparable cases to partially explain this puzzle. Both countries share many similar cultural and developmental backgrounds. One-party dominance in Taiwan failed in the 1980s when Taiwan became modern. But in Singapore, the one-party regime survived the opposition’s challenges in the 1960s and has remained stable since then. There are few comparative studies of these two countries. Through empirical studies of the two cases, I conclude that regime structure, i.e., clientelistic versus professional structure, affects the chances of authoritarian survival after the society becomes modern. This conclusion is derived from a two-country comparative study. Further research is necessary to test if the same conclusion can be applied to other cases. This research contributes to the understanding of one-party-dominant regimes in modernizing societies. ii Dedication Dedicated to the Lord, Jesus Christ. “Counsel and sound judgment are mine; I have insight, I have power. By Me kings reign and rulers issue decrees that are just; by Me princes govern, and nobles—all who rule on earth.” Proverbs 8:14-16 iii Acknowledgments I thank my committee members Professor R. -

Flogging Gum: Cultural Imaginaries and Postcoloniality in Singaporeâ

Law Text Culture Volume 18 The Rule of Law and the Cultural Article 10 Imaginary in (Post-)colonial East Asia 2014 Flogging Gum: Cultural Imaginaries and Postcoloniality in Singapore’s Rule of Law Jothie Rajah American Bar Foundation Follow this and additional works at: http://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc Recommended Citation Rajah, Jothie, Flogging Gum: Cultural Imaginaries and Postcoloniality in Singapore’s Rule of Law, Law Text Culture, 18, 2014, 135-165. Available at:http://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol18/iss1/10 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Flogging Gum: Cultural Imaginaries and Postcoloniality in Singapore’s Rule of Law Abstract One of the funny things about living in the United States is that people say to me: ‘Singapore? Isn’t that where they flog you for chewing gum?’ – and I am always tempted to say yes. This question reveals what sticks in the popular US cultural imaginary about tiny, faraway Singapore. It is based on two events: first, in 1992, the sale of chewing gum was banned (Sale of Food [Prohibition of Chewing Gum] Regulations 1992), and second, in 1994, 18 year-old US citizen, Michael Fay, convicted of vandalism for having spray-painted some cars was sentenced to six strokes of the cane (Michael Peter Fay v Public Prosecutor).1 If Singapore already had a reputation for being a nanny state, then these two events simultaneously sharpened that reputation and confused the stories into the composite image through which Americans situate Singaporeans. -

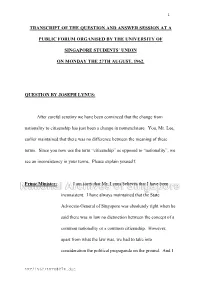

Transcript of the Question and Answer Session at a Public Forum Organised by the University of Singapore Students' Union on Mo

1 TRANSCRIPT OF THE QUESTION AND ANSWER SESSION AT A PUBLIC FORUM ORGANISED BY THE UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE STUDENTS’ UNION ON MONDAY THE 27TH AUGUST, 1962. QUESTION BY JOSEPH LYNUS: After careful scrutiny we have been convinced that the change from nationality to citizenship has just been a change in nomenclature. You, Mr. Lee, earlier maintained that there was no difference between the meaning of these terms. Since you now use the term “citizenship” as opposed to “nationality”, we see an inconsistency in your terms. Please explain yourself. Prime Minister: I am sorry that Mr. Lynus believes that I have been inconsistent. I have always maintained that the State Advocate-General of Singapore was absolutely right when he said there was in law no distinction between the concept of a common nationality or a common citizenship. However, apart from what the law was, we had to take into consideration the political propaganda on the ground. And I LKY/1962/LKY0827B.doc 2 say this, quite simply, my enemies took a dangerous line when they had insisted that citizenship was different from nationality and they wanted citizenship. Well, you remember Mr. Marshall, he is a man not unlearned in the law, he came before this very same gathering two months ago, and he said this: “We do not quarrel about proportional representation. “We do not quarrel about with their insistence that Singapore politicians should vote or stand for election in the Federation. So we say, ‘we accept it Tengku, but let us have a common citizenship and let us have a common constitutional disability that no Federation citizen can stand or vote in Singapore. -

Singapore Before 1800 – by Kwa Chong Guan and Peter Borschberg (Eds.) Authors: Lisa Phongsavath, Martina Yeo Huijun

Global histories a student journal Review: Studying Singapore Before 1800 – By Kwa Chong Guan and Peter Borschberg (eds.) Authors: Lisa Phongsavath, Martina Yeo Huijun DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/GHSJ.2019.320 Source: Global Histories, Vol. 5, No. 1 (May 2019), pp. 156-161 ISSN: 2366-780X Copyright © 2019 Lisa Phongsavath, Martina Yeo Huijun License URL: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Publisher information: ‘Global Histories: A Student Journal’ is an open-access bi-annual journal founded in 2015 by students of the M.A. program Global History at Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. ‘Global Histories’ is published by an editorial board of Global History students in association with the Freie Universität Berlin. Freie Universität Berlin Global Histories: A Student Journal Friedrich-Meinecke-Institut Koserstraße 20 14195 Berlin Contact information: For more information, please consult our website www.globalhistories.com or contact the editor at: [email protected]. Studying Singapore Before 1800 – by Kwa Chong Guan and Peter Borschberg (eds.), Singapore: NUS Press, 2018. $45.00 SGD, Pp. 600, ISBN: 978-981-4722-74-2 Reviewed by: LISA PHONGSAVATH & YEO HUIJUN MARTINA L i s a P In 1969, Raffles Professor of History atthe University of Singapore, K.G. h o n Tregonning, proclaimed that modern Singapore began in the year 1819. Referring g s a v to Stamford Raffles’ establishment of a British settlement in what was deemed a a t h largely uninhabited island along the Melaka Strait, he states: & Y e o H u i j u n ‘Nothing that occurred on the island prior to this M a has particular relevance to an understanding of the r t i n 1 a contemporary scene; it is of antiquarian interest only’. -

Sir Stamford Raffles - a Manufactured Hero?1

1 SIR STAMFORD RAFFLES - A MANUFACTURED HERO?1 Nadia Wright University of Melbourne Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles (1781-1826) was an extraordinary man. A hard working official of the East India Company, he was appointed Lieutenant-Governor of Java and later of Bencoolen2 on Sumatra. As well, he was a scholar, whose History of Java3 earned him a knighthood, and a naturalist who was a co-founder of the London Zoo. He is, however, better known as the founder of Singapore. Since the first book-length biography of Raffles appeared in 1897,4 he has been the subject of more than sixteen biographical works. All of these, bar H. F. Pearson’s This Other India,5 eulogize Raffles, carefully crafting him into a seemingly unassailable hero. 1 This paper was presented to the 17th Biennial Conference of the Asian Studies Association of Australia in Melbourne 1-3 July 2008. It has been peer reviewed via a double blind referee process and appears on the Conference Proceedings Website by the permission of the author who retains copyright. This paper may be downloaded for fair use under the Copyright Act (1954), its later amendments and other relevant legislation. 2 Now called Bengkulu 3 Thomas Stamford Raffles, The History of Java. 2 vols. London: Printed for Black, Parbury and Allen, and John Murray, 1817. 4 Demetrius Boulger, The Life of Sir Stamford Raffles Amsterdam: The Pepin Press, 1999. Reprint. 5 H. F. Pearson, This Other India: A Biography of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 1957. 2 In the first part of this paper I examine how Raffles has been manufactured into a hero, and in the second consider why, and then the consequences of this valorisation.