Omct Annual Report05 Eng View

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mémento Statistique Du Canton De Genève 2017 Mouvement De La Population

2017 MÉMENTO STATISTIQUE DU CANTON DE GENÈVE SOMMAIRE Canton de Genève 1-17 Population et mouvement de la population 1 Espace et environnement 3 Travail et rémunération 4 Prix, immobilier et emploi 5 Entreprises, commerce extérieur et PIB 6 Banques et organisations internationales 7 Agriculture et sylviculture 8 Construction et logement 9 Energie et tourisme 10 Mobilité et transports 11 Protection sociale 12 Santé 13 Education 14 Culture et politique 15 Finances publiques, revenus et dépenses des ménages 16 Justice, sécurité et criminalité 17 Communes genevoises 18-26 Cartes 18 Population 19 Espace et environnement 21 Emploi 22 Construction et logement 23 Education 24 Politique 25 Finances publiques 26 Cantons suisses 27 Genève et la Suisse 28 EXPLICATION DES SIGNES ET ABRÉVIATIONS - valeur nulle 0 valeur inférieure à la moitié de la dernière position décimale retenue ... donnée inconnue /// aucune donnée ne peut correspondre à la définition e valeur estimée p donnée provisoire ♀ femme ÉDITION Responsable de la publication : Roland Rietschin Mise en page : Stéfanie Bisso Imprimeur : Atar Roto Presse SA, Genève Tirage : 7 000 exemplaires. © OCSTAT, Genève, juin 2017 Reproduction autorisée avec mention de la source POPULATION RÉSIDANTE 1 POPULATION SELON L’ORIGINE 2006 2016 2016 (%) Genevois 153 394 181 344 36,7 Confédérés 120 796 112 242 22,7 Etrangers 171 116 200 120 40,5 Total 445 306 493 706 100,0 POPULATION SELON L’ÂGE (2016, en %) Hommes Femmes Total 0 - 19 ans 22,1 19,8 20,9 20 - 39 ans 29,1 28,0 28,5 40 - 64 ans 34,6 33,7 34,1 65 -

Communes\Communes - Renseignements\Contact Des Communes\Communes - Renseignements 2020.Xlsx 10.12.20

TAXE PROFESSIONNELLE COMMUNALE Contacts par commune No COMMUNE PERSONNE(S) DE CONTACT No Tél No Fax E-mail [email protected] 1 Aire-la-Ville Claire SNEIDERS 022 757 49 29 022 757 48 32 [email protected] 2 Anières Dominique LAZZARELLI 022 751 83 05 022 751 28 61 [email protected] 3 Avully Véronique SCHMUTZ 022 756 92 50 022 756 92 59 [email protected] 4 Avusy Michèle KÜNZLER 022 756 90 60 022 756 90 61 [email protected] 5 Bardonnex Marie-Laurence MICHAUD 022 721 02 20 022 721 02 29 [email protected] 6 Bellevue Pierre DE GRIMM 022 959 84 34 022 959 88 21 [email protected] 7 Bernex Nelly BARTHOULOT 022 850 92 92 022 850 92 93 [email protected] 8 Carouge P. GIUGNI / P.CARCELLER 022 307 89 89 - [email protected] 9 Cartigny Patrick HESS 022 756 12 77 022 756 30 93 [email protected] 10 Céligny Véronique SCHMUTZ 022 776 21 26 022 776 71 55 [email protected] 11 Chancy Patrick TELES 022 756 90 50 - [email protected] 12 Chêne-Bougeries Laure GAPIN 022 869 17 33 - [email protected] 13 Chêne-Bourg Sandra Garcia BAYERL 022 869 41 21 022 348 15 80 [email protected] 14 Choulex Anne-Françoise MOREL 022 707 44 61 - [email protected] 15 Collex-Bossy Yvan MASSEREY 022 959 77 00 - [email protected] 16 Collonge-Bellerive Francisco CHAPARRO 022 722 11 50 022 722 11 66 [email protected] 17 Cologny Daniel WYDLER 022 737 49 51 022 737 49 50 [email protected] 18 Confignon Soheila KHAGHANI 022 850 93 76 022 850 93 92 [email protected] 19 Corsier Francine LUSSON 022 751 93 33 - [email protected] 20 Dardagny Roger WYSS -

Un Nouveau Parcours Pour La Ligne B Informations Officielles

INFORMATIONS OFFICIELLES Mobilité UN NOUVEAU PARCOURS POUR LA LIGNE B INFORMATIONS OFFICIELLES Chens-sur-Léman Lac Léman Communes de la rive gauche du lac : Hermance-Village amélioration de l’offre en transports publics Triaz Villars Anières-Gravière Sous-Chevrens Monniaz-Hameau Dès le 11 décembre 2016, les habitants des communes d’Anières, Collonge- Chevrens Direction Veigy Anières-Chavannes Châtaignières Courson Turaines Bellerive, Corsier, Hermance, Jussy et Meinier bénéficieront d’une offre plus Courbes Anières- Gy-Temple Peupliers Bassy Foyer Baraque-à-Cloud Jussy-Bellebouche Anières-Village Anières-Douane large des TPG. Gy-Poste Anières- Jussy-Meurets Marguerite Mairie Maisons- Neuves Jussy-Château Nant-d’Aisy Corsier-Village La Chêna Le Soleil Jussy-Place Prés-Palais Merlinge La Loure Grâce à l’engagement financier des communes concernées, le tracé de la Repentance Murailles Corsier-Port Route de Corsinge Sionnet La Gabiule Saint- La Dame Meinier-Eglise * La Forge ligne B a été revu et prolongé, pour assurer une liaison facilitée dans la région Maurice Corsinge-Village Savonnière (Hôpital de Bellerive) Meinier-Tour Route de Presinge Route de Compois Route de Lullier Arve et Lac. Plus besoin de passer par Rive pour rejoindre les Trois-Chênes ou Route de Saint-Maurice Rouelbeau Meinier-Pralys Pallanterie Centre Horticole Collonge Meinier- Compois Puplinge ! Bois-Galland L’Abbaye Bellerive Essert Petray Carre-d’Amont Presinge Vésenaz- Rouette Bois-Caran Basselat Mancy Californie Bonvard La Bise Grand-Cara Capite Crêts-de-la-Capite Cara-Douane A raison d’un bus toutes les 60 minutes du lundi au vendredi et de 120 minutes Vésenaz Vésenaz- * Bornes La Belotte Eglise le samedi, la ligne B reliera en effet Jussy à Chens-sur-Léman, en passant Direction Rive Cornière Boissier Chemin des Princes Aumônes par Sionnet, Corsinge, Meinier, La Capite, Vésenaz, Collonge, St-Maurice, Ruth Puplinge-Mairie Rippaz Tour-Carrée Grésy La Repentance, Corsier, Anières et Hermance. -

4. Vesenaz - La Pallanterie – La Capite

4. VESENAZ - LA PALLANTERIE – LA CAPITE 4.1 Situation La route de Thonon est l'axe routier structurant entre La Pallanterie et Vésenaz. Cette fonction se double d'une fonction importante de transit pour les frontaliers se rendant au centre de Genève. Le secteur comporte deux pôles importants: > Vésenaz. Centre historique où se concentrent logements à moyenne densité et activités commerciales (services, grandes surfaces, etc.). Ce pôle connaît actuellement un développement soutenu. Le secteur Vésenaz - La Pallanterie – La- > La Pallanterie. Ce pôle d'activités plus récent s'est développé autour Capite du carrefour des routes de Thonon et de La Capite. On y retrouve es- sentiellement des activités artisanales, administratives, et quelques commerces. Ces deux pôles sont complétés par un troisième, La Capite. Cet ancien village-rue de taille modeste ne connaît qu'un développement très mo- deste. Les trois entités sont reliées par la zone de villas et forment une continui- La zone de villas de La Californie té bâtie sur tout le sud de la commune, jusqu'à La Pallanterie et Mancy. 4.1.1 Développement régional Le PDCant et le PAFVG envisagent tous deux une consolidation du pôle de Vésenaz (« centre périphérique » dans le PDCant, et « centralité locale » dans le PAFVG). De même le PAFVG entrevoit la possibilité d'un dévelop- pement important à La Pallanterie, identifiée comme périmètre straté- gique de développement. Vésenaz constitue déjà une centralité et la poursuite de son développe- ment est en partie planifiée (PLQ approuvés sur tous les terrains libres). Tout développement supplémentaire nécessiterait des déclassements de terrains. Les lignes directrices (LD) du Chablais confirment les options retenues dans le PAFVG. -

Flyer Activités Sportives 6 Communes Vok.Indd

B�����-���� ���� �� ���� ���� ! Les communes de Choulex, Gy, Jussy, Meinier, Presinge et Puplinge vous proposent une multi tude d’acti vités sporti ves. Le tableau ci-dessous vous donne un bref aperçu des off res proposées dans votre commune et aux alentours. Au verso, vous trouverez les coordonnées des clubs, des associati ons ou des personnes qui organisent des cours. Contactez-les directement, ils se feront un plaisir de vous renseigner sur leurs cours, leurs horaires et leurs tarifs att racti fs. ACTIVITES CHOULEX GY JUSSY MEINIER PRESINGE PUPLINGE Art marti al • • • Att elage • Badminton • • Ball-trap • Boxe • Danse • • • Équitati on • • • Football • • • Gym • • • • • • Gym aînés / seniors • • • • Gym Pilates • • • Marche / Walking • Netball • Parkour • Pétanque • • Plongée • Ski • Tennis • • • • Tennis de table • Tir • Tir à l’arc • Volleyball • Yoga • • • • • Zumba • • Choulex Gy Jussy Meinier Presinge Puplinge Mairie de Choulex Mairie de Gy Mairie de Jussy Mairie de Meinier Mairie de Presinge Mairie de Puplinge Ch. des Briff ods 13 Rte de Gy 164 Rte de Jussy 312 Rte de Gy 17 Rte de Presinge 116 Rue de Graman 70 1244 Choulex 1251 Gy 1254 Jussy 1252 Meinier 1243 Presinge 1241 Puplinge www.choulex.ch www.mairie-gy.ch www.jussy.ch www.meinier.ch www.presinge.ch www.puplinge.ch [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 022.750.15.39 022.759.15.33 022.888.15.15 022.722.12.12 022.759.12.52 022.860.84.40 ART MARTIAL EQUITATION • Gym des aînés mixte - R. Niggli SKI • Krav Maga - N. -

Geneva : 45 Communes

Geneva : 45 communes al Aire-la-Ville co Gy am Anières cp Hermance an Avully cq Jussy ao Avusy cr Laconnex ap Bardonnex cs Ville de Lancy aq Bellevue ct Meinier ar Bernex dk Meyrin as Ville de Carouge dl Onex at Cartigny dm Perly Certoux bk Céligny dn Plan-les-Ouates bl Chancy do Pregny Chambesy bm Chêne-Bougeries dp Presinge bn Chêne-Bourg dq Puplinge bo Choulex dr Russin bp Collex-Bossy ds Satigny bq Collonge-Bellerive dt Soral br Cologny ek Thônex bs Confi gnon el Troinex bt Corsier em Vandoeuvres ck Dardagny en Vernier cl Genève eo Versoix cm Genthod ep Veyrier cn Grand-Saconnex IF YOU HAVE DIFFICULTY READING THESE TEXTS, A LARGE FORMAT (A4) VERSION IS AVAILABLE ON : www.ge.ch/integration/publications OR BY CONTACTING THE OFFICE FOR INTEGRATION OF FOREIGNERS, al RUE PIERRE FATIO 15 (4th FLOOR) 1204 GENEVA TEL. 022 546 74 99 www.ge.ch/integration [email protected] 2 WELCOME TO GENEVA - MESSAGE On behalf of the Council of State of the Canton of Geneva and the Association of Geneva Communes (ACG), we extend you a hearty welcome. Geneva has been a place of asylum and refuge for victims of religious persecution since the 16th century, with over a third of its population made up of foreigners. Diversity remains one of the major strengths of Geneva society, in which 194 nationalities are represented today, and solidarity and respect for cultural differences are among the priorities of the political and administrative authorities of both the Canton and the communes of Geneva. -

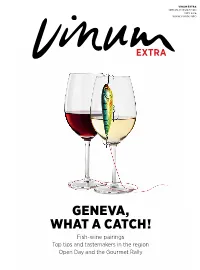

Geneva, What a Catch! Fish-Wine Pairings Top Tips and Tastemakers in the Region Open Day and the Gourmet Rally 04

VINUM EXTRA SPECIAL PUBLICATION MAY 2016 WWW.Vinum.INFO EXTRA GENEVA, WHAT A CATCH! Fish-wine pairings Top tips and tastemakers in the region Open Day and the Gourmet Rally 04 12 08 10 06 Selected highlights from this special issue: our interview with Chandra Kurt, ambassador of the 2015 vintage (page 4); tasting the winners of the Sélection des Vins de Genève contest (page 6); Open Day 2016 (page 8); the Gourmet Rally 2016 (page 10) and our special report on match- ing Geneva wines with fish (page 12 onwards). Read the “Geneva 2016” VINUM Special on your tablet: download the app for free now. Further information: www.vinum.info/ appangebote Contents 04 2015 vintage Editorial Interview with Chandra Kurt, Ambassador for this vintage What a catch! 06 Sélection des Vins de Genève The Sanglier, the Marcassin and the other prize-winners from e often find ourselves marvelling at the dynamism of this constantly- the 2015 awards evolving wine region, and singing the praises of its inimitable local pro- duce, so much so that we occasionally forget just how central the iconic W 08 Open Day lake is to the identity of Romandy’s biggest city. Lake Geneva is the soul of the region, a natural treasure celebrated in all its glory in this special issue. Lake Geneva, or Lac Behind the scenes at a small estate Léman to the French-speaking community, is home to around thirty species of fish and a big winery and shellfish. Unfortunately, perch remains an all too familiar sight on Swiss menus (95% of the fillets consumed in Switzerland are actually imported from Eastern 10 Gourmet Rally 2016 Europe or Africa). -

Map of Fare Zone

Fares Public transport for Geneva Map of Fare Zone as of Dec. 15 2019 Évian-les-Bains Plan tarifaire 300 L1 Thonon-les-Bains Légende Legend Toward Lausanne LignesTrain lines ferroviaires Lac Léman Perrignier Coppet LignesBus and de tram bus etlines tram Chens-sur-Léman LignesTransalis Transalis lines L1 L2 L3 L4 RE Gex Tannay LignesLacustre navettes shuttle lacustre lines Hermance-Village Customs Veigy-Foncenex, Les Cabrettes Bons-en-Chablais Divonne-les-Bains Mies PassageZone crossing de zone Chavannes-des-Bois Hermance Veigy-Foncenex ZoneLéman Léman Pass Pass zones Veigy- Veigy-Village Bois-Chatton Versoix Zoneunireso 10 zoneunireso 10 Pont-Céard Douane 200 Machilly Collex-Bossy Versoix Anières Customs Gy 250 Customs Bossy Genthod Creux-de-Genthod Anières-Douane Corsier Meinier Jussy St-Genis-Pouilly Ferney-Douane Genthod-Bellevue Bellevue Customs Grand-Saconnex-Douane Collonge-Bellerive Ferney-Bois Candide Les Tuileries Customs Le Grand-Saconnex Mategnin Chambésy Choulex Meyrin-Gravière Pregny- Chambésy 10 Genève-Aéroport Genève-Sécheron Vésenaz Presinge Customs Meyrin L1 Saint-Genis-Porte de France L2 Vandœuvre Meyrin L3 CERN 10 De-Chateaubriand Puplinge Thoiry Vernier L4 RE Ville-la-Grand Vernier Gare de Genève Pâquis Port-Noir Zimeysa Chêne-Bourg Annemasse Satigny Ambilly Eaux-Vives Chêne-Bougeries Genève Annemasse Satigny Gaillard- Molard Chêne-Bourg Customs Libération L1 L2 L3 L4 RE Etrembières Le Rhône 10 Genève-Eaux-Vives Moillesulaz 240 Russin Genève-Champel Gaillard 210 Lancy-Pont-Rouge Thônex Russin Dardagny Onex Challex -

Meinier 31 Gy 32 Cologny 27 Choulex 28 Presinge 29

GUIDE ZWISCHEN ARVE UND SEE Im Eichenfass ausgebaut, überzeugt dieser Rot- COLOGNY 27 wein mit Struktur und Aromatik. Dunkle, pur- purrote Farbe, expressives Duftbild aus Heidel- beergelee und Waldbeeren, klarer Auftakt, am Gaumen viel Körper und feine Tannine, über- schwängliches, zartwürziges Finale. Cave Les Coudrays www.domaineducrest.ch Jacques Baudet Domaine de la Vigne Blanche Le Rubis de Genève 2016 Domaine Château L’Evêque Sarah Meylan Die nach Bio Suisse zertifizierte Assemblage mit Martine Saucy Mévaux und Alexandre Mévaux Esprit de Genève 2018 Merlot, Gamay, Gamaret und Garanoir besitzt ein www.chateauleveque.ch Gamay (50 Prozent), Gamaret (30 Prozent) und komplexes Duftgeflecht aus Gewürzkräutern, Cabernet Franc (20 Prozent) aus dem Eichenfass milden Gewürzen und roten Früchten. Der schön fügen sich hier zu einem körperreichen, rassigen ausbalancierte, animierende Geschmack wird MEINIER 31 Gewächs mit eindeutiger Signatur: granatrote von geschmeidigen Tanninen getragen. Farbe, Duft geflecht aus Waldfrüchten mit Holz- www.lescoudrays.ch Domaine de la Tour noten, strukturierter, saftiger Geschmacksein- Cédric Béné druck. Familie Jean Rivolet Tel. +41 (0)22 750 02 28 www.lavigneblanche.ch Tel. + 41 (0)22 750 17 66 Domaine d’En Bruaz Grégory Favre CHOULEX 28 PRESINGE 29 www.domainedenbruaz.ch Domaine de l’Abbaye Ferme Jaquet Familie Läser Marc Jaquet Tel. +41 (0)22 759 17 52 www.ferme-jacquet.ch Domaine de Miolan JUSSY 30 GY 32 Bertrand Favre Gamaret 2018 Cave La Gara Cave de la Chena Dieser intensive Gamaret mit dem Bio-Suisse- Olivier Pradervand Daniel Fonjallaz Label imponiert mit dichter, ja fast undurchsichti- Tel. +41 (0)79 281 44 00 www.cavedelachena.ch ger Farbe, einem kräftigen Fruchtbouquet mit Noten von milden Gewürzen, strukturierter Gau- Clos de la Zone menaromatik, mundwässerndem, fruchtigem Robin und Valentin Vidonne Saft und seidigen Tanninen. -

Extension De La Zone Industrielle Et Artisanale De La Pallanterie

Fondation de la Pallanterie Extension de la zone industrielle et artisanale de la Pallanterie Plan directeur de zone de développement industrielle et artisanale «Pallanterie-Sud» Rapport explicatif A. Diagnostic préliminaire B. Schéma directeur de gestion et d’évacuation des eaux C. Etude pédologique et plan de gestion des sols D. Concept nature et paysage E. Concept énergétique territorial F. Concept mobilité G. Concept urbanisation H. Taxe d’équipement I. Rapport 47 OAT Adopté par le Conseil d’État le : 26.07.2017 Agence LMLV │ Créateurs immobiliers │ CSD │ Trafi tec 3 Extension de la zone industrielle et artisanale de la Pallanterie Groupement Pilotes et urbanistes : Agence LMLV Luc Malnati Leonard Verest Marion Penelas Jasmine Cortat Ingénieurs en environnement : CSD Eric Säuberli Clémentine Vautey Jean-Marc Dorsaz Romain Tagand Alice Metz Ingénieurs en mobilité : Trafi tec Michel Savary Felice Tufarolo Maurice Fabbretti Expert foncier : Créateurs Immobiliers François Dieu Géomètres : HKD Samuel Dunant Gérard Launay Maîtres d’ouvrage : FITIAP Moreno Sella Pierre Ambrosetti Jérôme Béné Olivier Morzier Genève, le 28 septembre 2016 Fondation de la Pallanterie 5 Extension de la zone industrielle et artisanale de la Pallanterie Table des matières Préambule . 7 A. Diagnostic préliminaire Introduction . 3 1. Planifications associées au site . 3 2. Contraintes et enjeux. 17 3. Premiers éléments de programmation . 36 B. Schéma directeur de gestion et d’évacuation des eaux 1. Introduction . 3 2. Données de base. 4 3. Schéma directeur de gestion des eaux. 10 Devis estimatif et clé de répartition. 22 C. Etude pédologique et plan de gestion des sols 1. Introduction . 3 2. Définitions et bases légales . -

Here's the Least Expensive Place to Live

Investment Solutions & Products Swiss Economics Here’s the least expensive place to live Financial residential attractiveness| May 2021 Financial residential attractiveness RDI indicator 2021 Results for your household What's left after subtracting all mandatory Life in the city centers is expensive, but there are Here’s the least expensive place for you to live charges and fixed costs? often more attractive municipalities close by Page 9 Page 29 Page 46 Masthead Publisher: Credit Suisse AG, Investment Solutions & Products Dr. Nannette Hechler-Fayd'herbe Head of Global Economics & Research +41 44 333 17 06 nannette.hechler-fayd'[email protected] Dr. Sara Carnazzi Weber Head of Policy & Thematic Economics +41 44 333 58 82 [email protected] Editorial deadline May 4, 2021 Orders Electronic copies via credit-suisse.com/rdi Copyright The publication may be quoted provided the source is identified. Copyright © 2021 Credit Suisse Group AG and/or affiliate companies. All rights reserved. Source references Credit Suisse unless specified Authors Dr. Jan Schüpbach +41 44 333 77 36 [email protected] Emilie Gachet +41 44 332 09 74 [email protected] Pascal Zumbühl +41 44 334 90 48 [email protected] Dr. Sara Carnazzi Weber +41 44 333 58 82 [email protected] Contributions Fabian Diergardt Thomas Mendelin Marcin Jablonski Swiss Economics | Financial residential attractiveness 2021 2 Editorial Dear readers, For many people, choosing where to live is one of the most important decisions in life. In addition to geographical location and infrastructure, the availability of appropriate housing, emotional criteria and personal networks, financial factors also play a key role. -

WELCOME to GENEVA Practical Guide to Living in Geneva Anglais

WELCOME TO GENEVA PRACTICAL GUIDE TO LIVING IN GENEVA ANGLAIS REPUBLIQUE ET CANTON DE GENEVE Geneva : 45 communes al Aire-la-Ville co Gy am Anières cp Hermance an Avully cq Jussy ao Avusy cr Laconnex ap Bardonnex cs Ville de Lancy aq Bellevue ct Meinier ar Bernex dk Meyrin as Ville de Carouge dl Onex at Cartigny dm Perly Certoux bk Céligny dn Plan-les-Ouates bl Chancy do Pregny Chambesy bm Chêne-Bougeries dp Presinge bn Chêne-Bourg dq Puplinge bo Choulex dr Russin bp Collex-Bossy ds Satigny bq Collonge-Bellerive dt Soral br Cologny ek Thônex bs Confi gnon el Troinex bt Corsier em Vandoeuvres ck Dardagny en Vernier cl Genève eo Versoix cm Genthod ep Veyrier cn Grand-Saconnex IF YOU HAVE DIFFICULTY READING THESE TEXTS, A LARGE FORMAT (A4) VERSION IS AVAILABLE ON : www.ge.ch/integration/publications OR BY CONTACTING THE OFFICE FOR INTEGRATION OF FOREIGNERS, al RUE PIERRE FATIO 15 (4th FLOOR) 1204 GENEVA TEL. 022 546 74 99 FAX. 022 546 74 90 www.ge.ch/integration [email protected] 2 WELCOME TO GENEVA - MESSAGE On behalf of the Council of State of the Canton of Geneva and the Association of Geneva Communes (ACG) we wish you a very warm welcome. Geneva has been a place of asylum and refuge for victims of religious persecution since the 16th century and has always been conscious of the richness of its multicultural society and convinced that it is one of its major strengths which favours exchange, dialogue and creativity. In order to promote this cultural richness, symbolised by the presence of 194 nationalities in Geneva, the canton and the communes deploy a great effort to encourage integration, intercultural dialogue and respect for minorities.