Symbolic Anthropology in the Netherlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Structuralism 1. the Nature of Meaning Or Understanding

Structuralism 1. The nature of meaning or understanding. A. The role of structure as the system of relationships Something can only be understood (i.e., a meaning can be constructed) within a certain system of relationships (or structure). For example, a word which is a linguistic sign (something that stands for something else) can only be understood within a certain conventional system of signs, which is language, and not by itself (cf. the word / sound and “shark” in English and Arabic). A particular relationship within a شرق combination society (e.g., between a male offspring and his maternal uncle) can only be understood in the context of the whole system of kinship (e.g., matrilineal or patrilineal). Structuralism holds that, according to the human way of understanding things, particular elements have no absolute meaning or value: their meaning or value is relative to other elements. Everything makes sense only in relation to something else. An element cannot be perceived by itself. In order to understand a particular element we need to study the whole system of relationships or structure (this approach is also exactly the same as Malinowski’s: one cannot understand particular elements of culture out of the context of that culture). A particular element can only be studied as part of a greater structure. In fact, the only thing that can be studied is not particular elements or objects but relationships within a system. Our human world, so to speak, is made up of relationships, which make up permanent structures of the human mind. B. The role of oppositions / pairs of binary oppositions Structuralism holds that understanding can only happen if clearly defined or “significant” (= essential) differences are present which are called oppositions (or binary oppositions since they come in pairs). -

This Year in Jerusalem: Israel and the Literary Quest for Jewish Authenticity

This Year in Jerusalem: Israel and the Literary Quest for Jewish Authenticity The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Hoffman, Ari. 2016. This Year in Jerusalem: Israel and the Literary Quest for Jewish Authenticity. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33840682 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA This Year in Jerusalem: Israel and the Literary Quest for Jewish Authenticity A dissertation presented By Ari R. Hoffman To The Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the subject of English Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 15, 2016 © 2016 Ari R. Hoffman All rights reserved. ! """! Ari Hoffman Dissertation Advisor: Professor Elisa New Professor Amanda Claybaugh This Year in Jerusalem: Israel and the Literary Quest for Jewish Authenticity This dissertation investigates how Israel is imagined as a literary space and setting in contemporary literature. Israel is a specific place with delineated borders, and is also networked to a whole galaxy of conversations where authenticity plays a crucial role. Israel generates authenticity in uniquely powerful ways because of its location at the nexus of the imagined and the concrete. While much attention has been paid to Israel as a political and ethnographic/ demographic subject, its appearance on the map of literary spaces has been less thoroughly considered. -

Symbols and Rituals: an Interpretive Approach to Faith- Based Behavior

SYMBOLS AND RITUALS: AN INTERPRETIVE APPROACH TO FAITH- BASED BEHAVIOR By: James A. Forte Presented at: NACSW Convention 2014 November, 2014 Annapolis, Maryland | www.nacsw.org | [email protected] | 888-426-4712 | Symbols and Rituals: An Interpretive Approach to Faith-Based Behavior Presentation at National Association of Christian Social Workers, Annual Conference Annapolis, Maryland November 8, 2014 James A. Forte Professor, Salisbury University Symbols and Rituals (Geertz and Faith Behavior) Memorable Words “The phrase ‘nothing is a practical as good theory’ is a twist of an older truth: Nothing improves theory more than its confrontation with practice” (Hans Zetterberg, 1962, page 189). Symbols and Rituals (Geertz and Faith Behavior) Overview: Framework for Making Sense of Geertz’s Theory Models – Exemplary root theorists Metaphors – Theory’s root metaphors Mapping – Theoretical elements and relations, Translation to eco-map Method - Directives for further inquiry & theory use Middle-range Theory-based applications (Inquiry theorizing and planned change) Marks of Critical thinking about theory Excellence Symbols and Rituals (Geertz and Faith Behavior) Clifford Geertz and The Symbolic Anthropology Approach This approach to religion and spirituality provides an analysis of the system of meanings embodied in the symbols and expressed in rituals which make up the religion or spiritual system (for a focal social group), and the relating of these systems to social-structural and psychological processes (Geertz, 1973, page 125). Symbols -

CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS: the Man and His Works

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nebraska Anthropologist Anthropology, Department of 1977 CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS: The Man and His Works Susan M. Voss University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebanthro Part of the Anthropology Commons Voss, Susan M., "CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS: The Man and His Works" (1977). Nebraska Anthropologist. 145. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebanthro/145 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Anthropologist by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in THE NEBRASKA ANTHROPOLOGIST, Volume 3 (1977). Published by the Anthropology Student Group, Department of Anthropology, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska 68588 21 / CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS: The Man and His Works by Susan M. Voss 'INTRODUCTION "Claude Levi-Strauss,I Professor of Social Anth- ropology at the College de France, is, by com mon consent, the most distinguished exponent ~f this particular academic trade to be found . ap.ywhere outside the English speaking world ... " (Leach 1970: 7) With this in mind, I am still wondering how I came to be embroiled in an attempt not only to understand the mul t:ifaceted theorizing of Levi-Strauss myself, but to interpret even a portion of this wide inventory to my colleagues. ' There is much (the maj ori ty, perhaps) of Claude Levi-Strauss which eludes me yet. To quote Edmund Leach again, rtThe outstanding characteristic of his writing, whether in French or in English, is that it is difficul tto unders tand; his sociological theories combine bafflingcoinplexity with overwhelm ing erudi tion"., (Leach 1970: 8) . -

El Infinito Y El Lenguaje En La Kabbalah Judía: Un Enfoque Matemático, Lingüístico Y Filosófico

El Infinito y el Lenguaje en la Kabbalah judía: un enfoque matemático, lingüístico y filosófico Mario Javier Saban Cuño DEPARTAMENTO DE MATEMÁTICA APLICADA ESCUELA POLITÉCNICA SUPERIOR EL INFINITO Y EL LENGUAJE EN LA KABBALAH JUDÍA: UN ENFOQUE MATEMÁTICO, LINGÜÍSTICO Y FILOSÓFICO Mario Javier Sabán Cuño Tesis presentada para aspirar al grado de DOCTOR POR LA UNIVERSIDAD DE ALICANTE Métodos Matemáticos y Modelización en Ciencias e Ingeniería DOCTORADO EN MATEMÁTICA Dirigida por: DR. JOSUÉ NESCOLARDE SELVA Agradecimientos Siempre temo olvidarme de alguna persona entre los agradecimientos. Uno no llega nunca solo a obtener una sexta tesis doctoral. Es verdad que medita en la soledad los asuntos fundamentales del universo, pero la gran cantidad de familia y amigos que me han acompañado en estos últimos años son los co-creadores de este trabajo de investigación sobre el Infinito. En primer lugar a mi esposa Jacqueline Claudia Freund quien decidió en el año 2002 acompañarme a Barcelona dejando su vida en la Argentina para crear la hermosa familia que tenemos hoy. Ya mis dos hermosos niños, a Max David Saban Freund y a Lucas Eli Saban Freund para que logren crecer y ser felices en cualquier trabajo que emprendan en sus vidas y que puedan vislumbrar un mundo mejor. Quiero agradecer a mi padre David Saban, quien desde la lejanía geográfica de la Argentina me ha estimulado siempre a crecer a pesar de las dificultades de la vida. De él he aprendido dos de las grandes virtudes que creo poseer, la voluntad y el esfuerzo. Gracias papá. Esta tesis doctoral en Matemática Aplicada tiene una inmensa deuda con el Dr. -

Symbolic Anthropology Symbolic Anthropology Victor Turner (1920

Symbolic Anthropology • Examines symbols & processes by which humans assign meaning. • Addresses fundamental Symbolic anthropology questions about human social life, especially through myth & ritual. ANTH 348/Ideas of Culture • Culture does not exist apart from individuals. • It is found in interpretations of events & things around them. Symbolic Anthropology Victor Turner (1920-1983) • Studied with Max Gluckman @ Manchester University. • Culture is a system of meaning deciphered by • Taught at: interpreting key symbols & rituals. • Stanford University • Anthropology is an interpretive not scientific • Cornell University • University of Chicago endeavor . • University of Virginia. • 2 dominant trends in symbolic anthropology • Publications include: • Schism & Continuity in an African Society (1957) represented by work of British anthropologist • The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual (1967) Victor Turner & American anthropologist • The Drums of Affliction: A Study of Religious Processes Among the Ndembu of Zambia Clifford Geertz. (1968) • The Ritual Process: Structure & Anti-Structure (1969). • Dramas, Fields, & Metaphors (1974) • Revelation & Divination in Ndembu Ritual (1975) Social Drama Social drama • • Early work on village-level social processes among the For Turner, social dramas have four main phases: Ndembu people of Zambia 1. Breach –rupture in social relations. examination of demographics & economics. 2. Crisis – cannot be handled by normal strategies. • Later shift to analysis of ritual & symbolism. 3. Redressive action – seeks to remedy the initial problem, • Turner introduced idea of social drama redress and re-establish • "public episodes of tensional irruption*” 4. Reintegration or schism – return to status quo or an • “units of aharmonic or disharmonic process, arising in conflict situations.” alteration in social arrangements. • They represent windows into social organization & values . -

The Theoretical Kabbalah

SES Kabbalah Course Segment 4 The Theoretical Kabbalah The most lasting product of the Provençal and Spanish schools of Kabbalah was compilation and publication of the classical Kabbalistic texts: the Sefer Yetzirah, the Sefer ha-Bahir, and the Sefer ha-Zohar. The Spanish Rabbi Moses de Léon (c.1250–1305) published the Zohar at roughly the same time when Abraham Abulafia was writing about the ecstatic Kabbalah. Controversy over the Zohar’s origins may never be resolved, but the work emerged as a major Jewish sacred text. Without doubt it became the most significant text in the development of the theoretical Kabbalah. The Zohar provided all of the concepts on which the theoretical Kabbalah is based. But its full potential was not exploited for another 300 years. That task fell to an elite group of scholars who assembled at Safed, Galilee, in the 16th century. Moses Cordovero, Isaac Luria, and others codified the zoharic teachings and built the elaborate system of theoretical Kabbalah we recognize today. In this segment we shall learn more about the Ain Sof and the sefiroth. We shall study the Kabbalistic story of creation, fall and redemption; we shall meet the Shekinah, the feminine aspect of God; and we shall explore the human soul and reflect on the role humanity can play in cosmic redemption. Specifically, this segment includes the following sections: • Cultural Context: From Southern Europe to Safed • The Divine Emanations • Creation, fall and redemption • The Shekinah • Humanity: Constitution and Behavior • Reflections, Resources, and Assignment. Cultural Context Exodus from Provence and Spain The Golden Age of southern European Kabbalism, discussed in Segment 2, came to an end as political changes undermined the environment in which generations of Jews had lived, worked, worshipped and studied. -

Spices from the East: Papers in Languages of Eastern Indonesia

Sp ices fr om the East Papers in languages of eastern Indonesia Grimes, C.E. editor. Spices from the East: Papers in languages of Eastern Indonesia. PL-503, ix + 235 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 2000. DOI:10.15144/PL-503.cover ©2000 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. Also in Pacific Linguistics Barsel, Linda A. 1994, The verb morphology of Mo ri, Sulawesi van Klinken, Catherina 1999, A grammar of the Fehan dialect of Tetun: An Austronesian language of West Timor Mead, David E. 1999, Th e Bungku-Tolaki languages of South-Eastern Sulawesi, Indonesia Ross, M.D., ed., 1992, Papers in Austronesian linguistics No. 2. (Papers by Sarah Bel1, Robert Blust, Videa P. De Guzman, Bryan Ezard, Clif Olson, Stephen J. Schooling) Steinhauer, Hein, ed., 1996, Papers in Austronesian linguistics No. 3. (Papers by D.G. Arms, Rene van den Berg, Beatrice Clayre, Aone van Engelenhoven, Donna Evans, Barbara Friberg, Nikolaus P. Himmelmann, Paul R. Kroeger, DIo Sirk, Hein Steinhauer) Vamarasi, Marit, 1999, Grammatical relations in Bahasa Indonesia Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in grammars and linguistic descriptions, dictionaries and other materials on languages of the Pacific, the Philippines, Indonesia, Southeast and South Asia, and Australia. Pacific Linguistics, established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund, is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at The Australian National University. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the School's Department of Linguistics. -

What's in a Meme?

What’s in a Meme? The Development of the Meme as a Unit of Culture Garry Chick The Pennsylvania State University University Park, Pennsylvania, USA Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Anthropological Association as part of the session, “Perceiving Culture: Unit Definition in Cultural Anthropology,” November 21, 1999. Please do not quote without permission. An earlier version of this paper is in press in Social Science Today (in Russian). Abstract Over the past 150 years numerous labels have been applied to the “parts” of culture. Some of these, including “themes,” “configurations,” “complexes,” and “patterns” are macro level. Micro level terms include “ideas,” “beliefs,” “values,” “rules,” “principles,” “symbols,” “concepts,” and a few others. The macro level labels often appear to be particular arrangements of micro level units. But which of these, if any, is the (or, an) operational unit of cultural transmission, diffusion, and evolution? Recently proposed units of cultural transmission typically derive from analogies made between cultural and biological evolution. Even though the unit of selection in biological evolution (i.e., the gene, the individual, or the group) is still under debate, the “meme,” originally suggested by Dawkins (1976) as a cultural analog of the gene, has been “selected” by many as a viable unit of culture. A “science of memes” (“memetics”) has been proposed (Lynch 1996) and numerous web sites devoted to the meme exist on the internet. This paper will trace the development of the meme and, in the process, critically address its utility as a unit of culture. 2 The whole history of science shows that advance depends upon going beyond “common sense” to abstractions that reveal unobvious relations and common properties of isolatable aspects of phenomena. -

Annual Report 2015

ANNUAL 2015 REPORT CONTENTS: 3 From the President 5 About the Jerusalem Foundation 7 Vision and Mission 9 Economic Growth 15 Education 21 Vulnerable Populations 31 Dialogue and Shared Living 41 Arts and Culture 49 Heritage Preservation 56 Financial Data 2015 60 Donors 65 Legacies and Estates 67 Leadership Israel 68 Leadership Worldwide Information in this report is correct as of May 1, 2016. The exchange rate utilized for this report is 3.8 NIS to $1 USD. Photos: Jerusalem Foundation staff, Michal Fatal, Meredith Holbrook, Sarah Gur Arie, Vadim Mikhailov, Sasson Tiram From the President Dear Friends, to maintain the pluralistic character of the city. Together with our investments in these areas, I am pleased to we continue to support programs that make present you with the the education system more attractive for young Jerusalem Foundation’s 2015 Annual Report, a families, as we lend a helping hand for vulnerable year in which $29.1 million in pledges and grants populations and take part in programs that were raised from our friends worldwide, for the encourage dialogue and shared living. benefit of Jerusalem and its residents. Fifty years ago, the legendary Mayor of Much has been accomplished in Jerusalem Jerusalem Teddy Kollek established the Jerusalem in 2015, but we cannot ignore the difficult Foundation, and today, we continue his mission circumstances the city has faced over the last to shape a modern and vibrant city, creating few months. Tourism has declined, businesses opportunities and engendering hope for all have closed their doors, and the unstable security Jerusalem’s residents. -

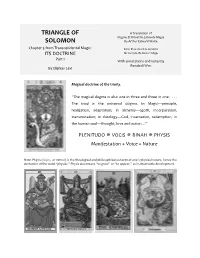

Triangle of Solomon

TRIANGLE OF A Translation of Dogme Et Rituel De La Haute Magie SOLOMON By Arthur Edward Waite Chapter 3 from Transcendental Magic: FIRST PUBLISHED IN LONDON ITS DOCTRINE BY GEORGE REDWAY 1896 Part I With annotations and notes by Benebell Wen By Eliphas Levi Magical doctrine of the trinity. “The magical dogma is also one in three and three in one. The triad is the universal dogma. In Magic—principle, realization, adaptation; in alchemy—azoth, incorporation, transmutation; in theology—God, incarnation, redemption; in the human soul—thought, love and action…” PLENITUDO VOCIS BINAH PHYSIS Manifestation Voice Nature Note: Physis (νόμος, or nomos) is the theological and philosophical concept of one’s physical nature, hence the derivation of the word “physics.” Physis also means “to grow” or “to appear,” as in observable development. Magical doctrine of the trinity. “The magical dogma is also one in three and three in one. The triad is the universal dogma. In Magic—principle, realization, adaptation; in alchemy—azoth, incorporation, transmutation; in theology—God, incarnation, redemption; in the human soul—thought, love and action…” PLENITUDO VOCIS BINAH PHYSIS Manifestation Voice Nature Note: Physis (νόμος, or nomos) is the theological and philosophical concept of one’s physical nature, hence the derivation of the word “physics.” Physis also means “to grow” or “to appear,” as in observable development. III. The Triangle of Solomon THE PERFECT WORD IS THE TRIAD, because it supposes an intelligent principle, a speaking principle, and a principle spoken. The absolute, revealing itself by speech, endows this speech with a sense equivalent to itself, and in the understanding thereof creates itself a third time. -

Zoologische Mededelingen Uitgegeven Door Het

ZOOLOGISCHE MEDEDELINGEN UITGEGEVEN DOOR HET RIJKSMUSEUM VAN NATUURLIJKE HISTORIE TE LEIDEN (MINISTERIE VAN CULTUUR, RECREATIE EN MAATSCHAPPELIJK WERK) Deel 56 no. 7 7 mei 1982 BIRD RECORDS FROM THE MOLUCCAS by G. F. MEES Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, Leiden Vom 2.-15. August 1876 sammelte Teysmann Vögel bei Kajeli, wovon niemals eine Liste publiciert wurde, da sie nach Leiden gelangten. E. Stresemann (1914b: 360). INTRODUCTION For the past thirty years I have, from time to time, come across bird material and literature records which have added localities and in a few instances have ad• ded new species, to Van Bemmel's (1948) list of birds of the Moluccan Islands and its supplement, published five years later (Van Bemmel & Voous, 1953). I have kept notes of these additions with the vague idea of perhaps, some time in the future, publishing a revised edition of the list of the avifauna of the Moluc• cas, zoogeographically one of the most interesting regions of the world. The sum total of my notes to date would hardly have justified publication, were it not for the fact that a new list of Moluccan birds was in the course of preparation by the late C. M. N. White, and is to be posthumously completed and published (cf. Benson, 1979; Cranbrook, 1980). This made it desirable to have my notes published, so that they will be available for inclusion in the new list. Ornithological activity in the Moluccas since the publication of Van BemmePs list has been limited. Many of De Haan's results were already incorporated in the paper by Van Bemmel & Voous (1953); subsequently two new subspecies from his collections were described by Jany (1955).