NOAA Series on U.S. Caribbean Fishing Communities Entangled

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Espacio, Tiempo Y Forma

ESPACIO, AÑO 2018 ISSN 1130-2968 TIEMPO E-ISSN 2340-146X Y FORMA 11 SERIE VI GEOGRAFÍA REVISTA DE LA FACULTAD DE GEOGRAFÍA E HISTORIA ESPACIO, AÑO 2018 ISSN 1130-2968 TIEMPO E-ISSN 2340-146X Y FORMA 11 SERIE VI GEOGRAFÍA REVISTA DE LA FACULTAD DE GEOGRAFÍA E HISTORIA DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5944/etfvi.11.2018 UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE EDUCACIÓN A DISTANCIA La revista Espacio, Tiempo y Forma (siglas recomendadas: ETF), de la Facultad de Geografía e Historia de la UNED, que inició su publicación el año 1988, está organizada de la siguiente forma: SERIE I — Prehistoria y Arqueología SERIE II — Historia Antigua SERIE III — Historia Medieval SERIE IV — Historia Moderna SERIE V — Historia Contemporánea SERIE VI — Geografía SERIE VII — Historia del Arte Excepcionalmente, algunos volúmenes del año 1988 atienden a la siguiente numeración: N.º 1 — Historia Contemporánea N.º 2 — Historia del Arte N.º 3 — Geografía N.º 4 — Historia Moderna ETF no se solidariza necesariamente con las opiniones expresadas por los autores. UNIVERSIDaD NacIoNal de EDUcacIóN a DISTaNcIa Madrid, 2018 SERIE VI · gEogRaFía N.º 11, 2018 ISSN 1130-2968 · E-ISSN 2340-146X DEpóSITo lEgal M-21.037-1988 URl ETF VI · gEogRaFía · http://revistas.uned.es/index.php/ETFVI DISEÑo y compoSIcIóN Carmen Chincoa Gallardo · http://www.laurisilva.net/cch Impreso en España · Printed in Spain Esta obra está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial 4.0 Internacional. ARTÍCULOS · ARTICLES ESPACIO, TIEMPO Y FORMA SERIE VI · GeografíA 11 · 2018 ISSN 1130-2968 · E-ISSN 2340-146x UNED 15 EVOLUCIÓN URBANA DE PONCE (PUERTO RICO), SEGÚN LA CARTOGRAFÍA HISTÓRICA URBAN EVOLUTION OF PONCE (PUERTO RICO), ACCORDING TO THE HISTORICAL CARTOGRAPHY Miguel A. -

Learn More at Music-Contact.Com Choral

Join choirs from across the United States and Canada at the Discover Puerto Rico Choral Music Contact International Festival. Perform for appreciative audiences in the culturally rich southern Puerto Rico city of H N T A N U 4 A Ponce. Broaden your understanding of the unique aspects of Caribbean and Puerto Rican choral 1 L traditions during a workshop at the Juan Morel Campos Institute of Music in Ponce. Choose between hotel accommodations in the historic city center of Ponce, or at a fabulous beachside resort. The City of Ponce welcomes your choir at the opening event hosted by city officials and featuring local performances. The citizens of Ponce rejoice in the festival’s main event, where visiting and local choirs will entertain the large and enthusiastic audience at the La Perla Theater on Sunday night. Celebrate Puerto Rico’s unique musical traditions during four days of singing and discover the beautiful sights and people of this lovely Caribbean island! “We have been on a fair number of other music AND ITS CHORAL MUSIC trips, and this was hands MARCH 13-16, 2020 down the best trip we've experienced. From the CHORAL SINGING IN THE cultural experiences to the HEART OF THE CARIBBEAN performance opportunities with Puerto Rican choirs, to the sightseeing. We couldn't be happier." Tami Haggard Thacher School 2015 Selection of Previous Participating Choirs • L'Anse Creuse High School, L'Anse Creuse, MI • Johnson State College, Johnson, VT LEARN MORE AT MUSIC-CONTACT.COM • Cabrini College, Radnor, PA EL MORRO • Wilshire United Methodist Church Choir, LA FORTALEZA Los Angeles, CA • Sidwell Friends School, Washington, DC PONCE • Faith Lutheran High School, Las Vegas, NV • St. -

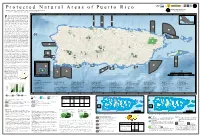

Protected Areas by Management 9

Unted States p Forest Department a Service DRNA of Agriculture g P r o t e c t e d N a t u r a l A r e a s o f P u e r to R i c o K E E P I N G C O M M ON S P E C I E S C O M M O N PRGAP ANALYSIS PROJECT William A. Gould, Maya Quiñones, Mariano Solórzano, Waldemar Alcobas, and Caryl Alarcón IITF GIS and Remote Sensing Lab A center for tropical landscape analysis U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry . o c 67°30'0"W 67°20'0"W 67°10'0"W 67°0'0"W 66°50'0"W 66°40'0"W 66°30'0"W 66°20'0"W 66°10'0"W 66°0'0"W 65°50'0"W 65°40'0"W 65°30'0"W 65°20'0"W i R o t rotection of natural areas is essential to conserving biodiversity and r e u P maintaining ecosystem services. Benefits and services provided by natural United , Protected areas by management 9 States 1 areas are complex, interwoven, life-sustaining, and necessary for a healthy A t l a n t i c O c e a n 1 1 - 6 environment and a sustainable future (Daily et al. 1997). They include 2 9 0 clean water and air, sustainable wildlife populations and habitats, stable slopes, The Bahamas 0 P ccccccc R P productive soils, genetic reservoirs, recreational opportunities, and spiritual refugia. -

Puerto Rico Coastal Zone Management Program

Puerto Rico Coastal Zone Management Program Revision and update September, 2009 CONTENTS Introduction................................................................................................................................................. 1 2.1 Sustainable Development ........................................................................................................................................ 4 2.1 Watershed as a Planning Unit ................................................................................................................................ 6 2.1 Non-point sources of pollution as a critical issue.......................................................................................... 6 Chapter I. Overview of Puerto Rico’s Coastal Zone .................................................................. 9 1.1 General Physical Characteristics ............................................................................................................................... 9 1.1.1 Origin and composition of the island ....................................................................................................... 9 1.1.2 The Island’s climate ....................................................................................................................................... 10 1.1.3 Natural systems ............................................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.4 Description of coastal sectors .................................................................................................................. -

Reflejos De La Historia De Puerto Rico En El Arte

MUSEO DE HISTORIA, ANTROPOLOGÍA Y ARTE UNIVERSIDAD DE PUERTO RICO, RECINTO DE RÍO PIEDRAS FUNDACIÓN PuertorriQUEÑA DE LAS HUMANIDADES National ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES 1751–1950 REFLEJOS DE LA HISTORIA DE PUERTO RICO EN EL ARTE 1751–1950 REFLEJOS DE LA HISTORIA DE PUERTO RICO EN EL ARTE H MAA Museo de Historia, Antropología y Arte Autorizado por la Comisión Estatal de Elecciones CEE-SA-16-4645 1751–1950 REFLEJOS DE LA HISTORIA DE PUERTO RICO EN EL ARTE LIZETTE CABRERA SALCEDO MUSEO DE HISTORIA, ANTROPOLOGÍA Y ARTE UNIVERSIDAD DE PUERTO RICO, RECINTO DE RÍO PIEDRAS FUNDACIÓN PuertorriQUEÑA DE LAS HUMANIDADES Esta publicación es parte del proyecto Reflejos de la Historia de Puerto Rico en el Arte: 1751−1950, subvencionado por la Fundación Puertorriqueña de las Humanidades, National Endowment for the Humanities MHAA Museo de Historia, Antropología y Arte Esta publicación es parte del proyecto Reflejos de la Historia de Puerto Rico en el Arte: 1751−1950, subvencionado por la Fundación Puertorriqueña de las Humanidades, National Endowment for the Humanities Primera Edición, 2015 Publicado por el Museo de Historia, Antropología y Arte Universidad de Puerto Rico, Recinto de Río Piedras PO Box 21908 San Juan, Puerto Rico 00931-1908 © 2015 Museo de Historia, Antropología y Arte Universidad de Puerto Rico, Recinto de Río Piedras ISBN 0-9740399-9-3 CONTENIDO 6 MENSAJES 8 INTRODUCCIÓN NUESTROS ORÍGENES 11 Asomo a la sociedad indígena de Boriquén 15 Las visiones de la conquista y colonización española 16 La Villa de Caparra 18 Exterminio de un -

A Cruising Guide to Puerto Rico

A Cruising Guide to Puerto Rico Ed. 1.0 by Frank Virgintino Flag of Puerto Rico Copyright © 2012 by Frank Virgintino. All rights reserved. www.freecruisingguides.com A Cruising Guide to Puerto Rico, Ed. 1.0 www.freecruisingguides.com 2 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................. 10 1. PREFACE AND PORT REFERENCES ....................................... 12 SOUTH COAST ......................................................................... 13 EAST COAST ............................................................................ 14 Mainland ................................................................................ 14 Islands .................................................................................... 15 NORTH COAST ......................................................................... 15 WEST COAST ........................................................................... 16 2. INTRODUCING PUERTO RICO ................................................ 17 SAILING DIRECTIONS TO PUERTO RICO .............................. 17 From North: ............................................................................ 17 From South: ............................................................................ 21 From East: .............................................................................. 22 From West: ............................................................................. 22 PUERTO RICAN CULTURE ...................................................... 23 SERVICES -

Adjuntas Y La Tourism Route 123

Rincón A Free Restaurant Guide Route 123 1 Bienvenida welcome Javier E. Zapata Rodríguez, EDFP Director, Rural Innovation Fund – Ruta 123 ¡Bienvenido a la Ruta 123! Puerto Rico ha sido reconocido mundialmente por sus playas, vida nocturna y variedad Welcome to Route 123! Puerto Rico has de entretenimiento. en adición, Puerto been recognized worldwide for its beaches, Rico cuenta con una gran diversidad de nightlife and variety of entertainment. In recursos naturales, históricos y culturales addition, Puerto Rico has a great diversity gracias a su profunda historia, enmarcada of natural, historical and cultural resources through its deep story, set on an island that pequeña, es gigante en la variedad de experiencias que ofrece al turista. although geographically small, is huge PathStone se siente orgulloso de in the variety of experiences offered to presentarle el corredor Agro-turístico tourists. Ruta 123. La Ruta 123 la componen los PathStone is proud to present the Agro- municipios de Ponce y Adjuntas y la tourism Route 123. Route 123 travels the región de Castañer. esta publicación towns of Ponce, Adjuntas and the Castañer resalta, respectivamente, sus mayores Region. this publication highlights, atracciones, hospederías, gastronomía respectively, the main attractions, inns, y varios tesoros escondidos esperando dining and several hidden treasures just ofrece una rica experiencia cultural con su variedad de museos, parques y Ponce offers a rich cultural experience with estructuras de valor arquitectónico. Se its variety of museums, parks and structures resalta en el municipio de Adjuntas sus of architectural value. Adjuntas stands valiosos recursos naturales, paradores y for its valuable natural resources, hostels gastronomía puertorriqueña. -

Puerto Rico Electric Power Authorit

NEPR Received: COMMONWEALTH OF PUERTO RICO Jun 3, 2021 PUBLIC SERVICE REGULATORY BOARD PUERTO RICO ENERGY BUREAU 4:38 PM IN RE: PUERTO RICO ELECTRIC POWER CASE NO.: NEPR-MI-2019-0006 AUTHORITY’S EMERGENCY RESPONSE PLAN SUBJECT: Submission of Annexes to Emergency Response Plan MOTION SUBMITING ANNEXES A, B AND C TO LUMA’S EMERGENCY RESPONSE PLAN TO THE HONORABLE PUERTO RICO ENERGY BUREAU: COME NOW LUMA Energy, LLC (“ManagementCo”)1, and LUMA Energy ServCo, LLC (“ServCo”)2, (jointly referred to as “LUMA”), and, through the undersigned legal counsel, respectfully submit the following: 1. LUMA respectfully informs that due to an involuntary omission, the pdf of the Emergency Response Plan (ERP) that was filed on May 31, 2021 with this honorable Puerto Rico Energy Bureau, omitted Annex A (Major Outage Restoration), Annex B (Fire Response) and Annex C (Earthquake Response) to the ERP. 2. LUMA hereby submits Annexes A, B and C to the ERP. See Exhibit 1. 3. To protect personal identifying information of LUMA personnel, the signature and name of the LUMA officer that is identified in each of the Annexes (page 5 of Annex A, Annex B and Annex C), were redacted. LUMA hereby requests that the referenced signature and name be kept confidential in accordance with Section 6.15 of Act 57-2014 (providing, that: “[i]f any person who is required to submit information to the Energy Commission believes that the information to 1 Register No. 439372. 2 Register No. 439373. -1 be submitted has any confidentiality privilege, such person may request the Commission to treat such information as such . -

Characterization of Benthic Habitats and Associated Mesophotic Coral Reef Communities at El Seco, Southeast Vieques, Puerto Rico

FINAL REPORT Characterization of benthic habitats and associated mesophotic coral reef communities at El Seco, southeast Vieques, Puerto Rico by: Jorge R. García-Sais, Jorge Sabater-Clavell, Rene Esteves, Jorge Capella, Milton Carlo P. O. Box 3424, Lajas, P. R. [email protected] Submitted to: Caribbean Fishery Management Council San Juan, Puerto Rico August 2011 i I. Executive summary This research forms part of an initiative by the Caribbean Fishery Management Council (CFMC) to explore, map and provide quantitative and qualitative characterizations of benthic habitats and associated fish and shellfish communities present within the Caribbean EEZ, Puerto Rico and the USVI, with particular interest on shelf areas that have been seasonally closed to fishing in protection of fish spawning aggregations such as that of tiger grouper (Mycteroperca tigris) at “El Seco”, Vieques, Puerto Rico. The main objectives of the study included the construction of a georeferenced benthic habitat map of the mesophotic zone at “El Seco” within a depth range of 30 – 50 m, along with a quantitative, qualitative and photographic characterization of the predominant sessile-benthic, fish and motile-megabenthic invertebrate communities associated with these mesophotic habitats. Production of the benthic habitat map was based on a series of field observations and habitat classifications of the main reef topographic features by rebreather divers, as suggested from a multi-beam bathymetry footprint produced by the R/V Nancy Foster (NOAA). A total of 75 stations were occupied for direct field verification of benthic habitats, including 40 -10 m long transects for determinations of percent cover by sessile-benthic categories and 40 - 20 m long x 3 m wide belt-transects for quantification of demersal reef fishes and motile megabenthic invertebrates. -

The Best of Puerto Rico

05_556282 ch01.qxd 6/16/04 10:53 AM Page 4 1 The Best of Puerto Rico Whatever you want to do on a tropical vacation or business trip—play on the beach with the kids (or gamble away their college funds), enjoy a romantic hon- eymoon, or have a little fun after a grueling negotiating session—you’ll find it in Puerto Rico. But you don’t want to waste precious hours once you get here searching for the best deals and the best experiences. We’ve done that work for you. During our years of traveling through the islands that form the Common- wealth of Puerto Rico, we’ve tested the beaches, toured the sights, reviewed countless restaurants, inspected hotels, and sampled the best scuba diving, hikes, and other outdoor activities. We’ve even learned where to get away from it all when it’s time to escape the crowds. Here’s what we consider to be the best that Puerto Rico has to offer. 1 The Best Beaches White sandy beaches put Puerto Rico mainly from New York. However, and its offshore islands on tourist straight people looking to meet maps in the first place. Many other someone while wearing swimwear Caribbean destinations have only will find plenty of lookers (and jagged coral outcroppings or black perhaps takers). See “Diving, Fish- volcanic-sand beaches that get very ing, Tennis & Other Outdoor hot in the noonday sun. The best Pursuits,” in chapter 6. beaches are labeled on the “Puerto • Best Beach for Families: Win- Rico” map on p. -

Puerto Rico Tourism Company Tourism Industry Update | Week of March 5, 2018

1 PUERTO RICO TOURISM COMPANY TOURISM INDUSTRY UPDATE | WEEK OF MARCH 5, 2018 STATE OF THE INDUSTRY AIRLINES CURRENTLY OPERATING TO AND FROM SJU • American Airlines • Condor • JetBlue • Sun Country Airlines • Air Antilles Express • Copa Airlines • Liat • Tradewind Aviation • Air Century • Cape Air • Pawa Dominicana • United • Air Sunshine • Delta • Seaborne • Vieques Air Link • Allegiant • Frontier • Southwest • Westjet 100+FLIGHTS • Avianca • InterCaribbean Airways • Spirit PER DAY • VIEQUES • 115 cruise shore excursions Fajardo to Vieques: 9 AM, 1 PM, 6:30 PM fully operational. Vieques to Fajardo 6 AM, 11 AM, 4:30 PM • Over 170,000 homeport passengers have embarked • CULEBRA over the last 120 days. Fajardo to Culebra: 4 AM, 9 AM, 3 PM, 7 PM SAN JUAN PORT FERRY SCHEDULE Culebra to Fajardo: 6:30 AM, 1 PM, 5 PM IS OPEN UPDATE • 85% (127 out of 148 endorsed Hotels) are open and operating. • 94% are open • Future Openings: (16 out of 17). El San Juan Hotel – Curio Collection by Hilton (October 1, 2018) • 47% (8 out of 17) Meliá Coco Beach, Río Grande (November 1, 2018) are open 24hrs. Caribe Hilton (January 1, 2019) See list on page 13 85% HOTELS OPEN CASINOS ARE OPEN GROUND TRANSPORTATION RESTAURANTS ARE OPEN MESONES GASTRONÓMICOS IS AVAILABLE • Ground transportation is operating as usual. • More than 1,885 restaurants are open around • 68% (15 out of 22) Mesones Gastronómicos the island, including Culebra & Vieques. are open for business. 1 is partially open. • 55 Tour Operators are open for business with capacity of service to 6,172 passengers. Aquamarina @ Parador Villa Parguera • 34 major car rental companies are open Casa Bavaria for business, with 95 dealers distributed El Ancla throughout the island. -

Puerto Rico Forest Action Plan

National Priorities Section Puerto Rico Forest Action Plan Submitted to: USDA is an equal opportunity provider, employer and lender. This publication was made possible through a grant from the USDA Forest Service CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................... 7 1. CONSERVING WORKING FOREST LANDSCAPES ................................................................................ 8 1. Continue land acquisition programs of key private forested land by available mechanisms ......... 8 2. Promote conservation easements on private forested land ........................................................... 10 3. Provide adequate conservation management for private forests through Forest Stewardship plans .................................................................................................................................................. 11 4. Develop forest and wildlife interpretation trainings ......................................................................... 12 5. Develop management information on agroforestry practices suitable for the Río Loco Watershed at Guánica Bay Watershed .............................................................................................................. 14 6. Increase capacity of community to manage trees ......................................................................... 16 7. Increase tree canopy cover and condition ....................................................................................