Sankhya Ghosh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DEPARTMENT of FOLKLORE University of Kalyani

DEPARTMENT OF FOLKLORE University of Kalyani COURSE CURRICULA OF M.A. IN FOLKLORE (Two- years Master’s Degree Programme under the Scheme of CBCS) Session: 2017-2018 and onwards As recommended by the Post Graduate Board of Studies (PGBoS) in Folklore in the meeting held on May 05, 2017 OPERATIONAL ASPECTS A. Timetable: 1) Class-hour will be of 1 hour and the time schedule of classes should be from 10.30 a.m. to 5.00 p.m. with 30 minutes lunch-break during 1.30 to 2.00 p.m., from Monday to Friday. Thus there shall be maximum 6 classes a day. 2) Normal 16 class-hours in a week may be kept for direct class instructions. The remaining 14 hours in a week shall be kept for Tutorial, Dissertation, Seminar, Assignments, Special Classes, holding class-tests etc. as may be required for the course. B. Course-papers and Allocation of Class-Hours per Course: 1) For evaluation purposes, each course shall be of 100 marks and for each course of 100 marks total number of direct instruction hours (theory/practical/field-training) shall be 48 hours. 2) The full course in 4 semesters shall be of total 1600 marks with total 16 courses (Fifteen Core Courses & One Open Course). In each semester, the course work shall be for 4 courses of total 400 marks. C. Credit Specification of the Course Curricula: M.A. Course in Folklore shall comprise 4 semesters. Each semester shall have 4 courses. In all, there shall be 16 courses of 4 credits each. -

Eforms Publication of SEM-VI, 2021 on 7-9-2021.Xlsx

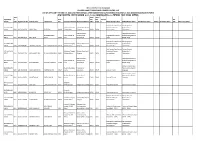

THE UNIVERSITY OF BURDWAN COLLEGE NAME- TARAKESWAR DEGREE COLLEGE- 415 LIST OF APPLICANT FOR SEM -VI, 2020 AND THEIR DETAILS AFTER SUBMITTING BA/BCOM/BSC (H/G) SEM-VI, 2021 ONLINE EXAMINATION FORM (যারা অনলাইন পেম কেরেছ ৯/০৭/২০২১ (বার) রাত ৮.০০ িমিনেটর মেধ তােদর তািলকা) Cours Hons/ Hons/ Application e Hons Gen Gen Gen Sub- SEC Seq No Code Registration No Student Name Father Name Sub Honours Sub CC-13 Honours Sub CC-14 Sub-1 Sub-2 3 DSE-3/1B Topic Name DSE-4/2BTopic Name DSE-3B Topic Name GE Sub GE-2 Topic Name Sub SEC-4 Topic Name Bish Sataker Swadhinata- Sahitya Bisayak 20216415AH0 Sanskrita O Ingreji Sahityer Rup- Riti O Purbabarti Bangla Prabandha O 29030 BAH 201501064828 SRIBAS BAG DILIP BAG BNGH Sahityer Itihas Sangrup BNGH BNGH Kathasahitya Lakasahitya Rabindranath's Stage Demonstration - 20216415AH0 DIPENDRA NATH Khyal Vilambit & Gitinatya and Stage Demonstration - Rabindra Sangeet and 33874 BAH 201501070379 ADITI BERA BERA MUCH Drut Nrityanatya MUCH MUCH Khyal Bengali Song Bish Sataker Swadhinata- Sahitya Bisayak 20216415AH0 Sanskrita O Ingreji Sahityer Rup- Riti O Purbabarti Bangla Prabandha O 28925 BAH 201601067467 CHANDRA SANTRA ASIT KUMAR SANTRA BNGH Sahityer Itihas Sangrup BNGH BNGH Kathasahitya Lakasahitya Bish Sataker Swadhinata- Sahitya Bisayak 20216415AH0 Sanskrita O Ingreji Sahityer Rup- Riti O Purbabarti Bangla Prabandha O 28717 BAH 201601073761 MADHUMITA BALI SHYAMSUNDAR BALI BNGH Sahityer Itihas Sangrup BNGH BNGH Kathasahitya Lakasahitya Rabindranath's Stage Demonstration - 20216415AH0 Khyal Vilambit & Gitinatya and -

IJRESS Volume 6, Issue 2

International Journal of Research in Economics and Social Sciences (IJRESS) Available online at: http://euroasiapub.org Vol. 7 Issue 7, July- 2017 ISSN(o): 2249-7382 | Impact Factor: 6.939 | Thomson Reuters Researcher ID: L-5236-2015 Dissemination of social messages by Folk Media – A case study through folk drama Bolan of West Bengal Mr. Sudipta Paul Research Scholar, Department of Mass Communication & Videography, Rabindra Bharati University Abstract: In the vicinity of folk-culture, folk drama is of great significance because it reflects the society by maintaining a non-judgemental stance. It has a strong impact among the audience as the appeal of Bengali folk-drama is undeniable. ‘Bolan’ is a traditional folk drama of Bengal which is mainly celebrated in the month of ‘Chaitra’ (march-april). Geographically, it is prevalent in the mid- northern rural and semi-urban regions of Bengal (Rar Banga area) – mainly in Murshidabad district and some parts of Nadia, Birbhum and Bardwan districts. Although it follows the theatrical procedures, yet it is different from the same because it has no female artists. The male actors impersonate as females and play the part. Like other folk drama ‘Bolan’ is in direct contact with the audience and is often interacted and modified by them. Primarily it narrates mythological themes but now-a-days it narrates contemporary socio-politico-economical and natural issues. As it is performed different contemporary issues of immense interest audiences is deeply integrated with it and try to assimilate the messages of social importance from it. And in this way Mass (traditional) media plays an important role in shaping public opinion and forming a platform of exchange between the administration and the people they serve. -

Department of Music Rabindra Sangeet Hons

Department of Music Rabindra Sangeet Hons. Section Nistarini College, Purulia (Govt. Sponsored and affliated to Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University) Course Outcome The I St paper (101) is Practical. This paper consists of Rabindra Sangeet of 6 Paryas Semester I (I) and some chota kheyals at preliminary level. Students learn the holistic concept of B.A. Hons in Music Rabindra Sangeet in the preliminary level. (Rabindra Sangeet) The 2nd Paper (102) is theoretical. Outline History of Music in Bengal and knowledge of`Raga and Tala GE1 Students of other Hons stream of Sem I and Programme course of Sem V develops foundation of basic knowledge of Rabindi.a Sangeet and chhota kheyal -Practical Paper. Semester 11 The paper 201 is Practical. This paper consists of selected songs based on various B.A. Hons in Music Paryas (]1). (Rabindra Sangeet) The paper 202 is theoretical - general i\'nowledge relating to influence of various songs on Rabindranath's creation. GE2 Students of other Hons stream of Sem 11 and Programme course of Sem Vl develops basic knowledge of selected songs based on various Paryas and knowledge of that ragas. Practical Paper. Two practical papers 301 - selected songs based on various tala coveriiig various Semester 111 Paryas' and types -I. B.A. Hons in Music 302 (Practical) - Selected songs based on various tala covering various Paryas' and types - 11. Paper 303 (Theory) -Knowledge of Ragas, talas and influence of folk (Rabindra Sangeet) songs on Rabindra Sangeet. SEC-1 paper (Theory) -General Aesthetics falls into this category. Semester IV Paper 401 (Practical) -Songs of Rabindranath covering various songs of six Paryas B.A. -

Wedding Videos

P1: IML/IKJ P2: IML/IKJ QC: IML/TKJ T1: IML PB199A-20 Claus/6343F August 21, 2002 16:35 Char Count= 0 WEDDING VIDEOS band, the blaring recorded music of a loudspeaker, the References cries and shrieks of children, and the conversations of Archer, William. 1985. Songs for the bride: wedding rites of adults. rural India. New York: Columbia University Press. Most wedding songs are textually and musically Henry, Edward O. 1988. Chant the names of God: musical cul- repetitive. Lines of text are usually repeated twice, en- ture in Bhojpuri-Speaking India. San Diego: San Diego State abling other women who may not know the song to University Press. join in. The text may also be repeated again and again, Narayan, Kirin. 1986. Birds on a branch: girlfriends and wedding songs in Kangra. Ethos 14: 47–75. each time inserting a different keyword into the same Raheja, Gloria, and Ann Gold. 1994. Listen to the heron’s words: slot. For example, in a slot for relatives, a wedding song reimagining gender and kinship in North India. Berkeley: may be repeated to include father and mother, father’s University of California Press. elder brother and his wife, the father’s younger brother and his wife, the mother’s brother and his wife, paternal KIRIN NARAYAN grandfather and grandmother, brother and sister-in-law, sister and brother-in-law, and so on. Alternately, in a slot for objects, one may hear about the groom’s tinsel WEDDING VIDEOS crown, his shoes, watch, handkerchief, socks, and so on. Wedding videos are fast becoming the most com- Thus, songs can be expanded or contracted, adapting to mon locally produced representation of social life in the performers’ interest or the length of a particular South Asia. -

Arts-Integrated Learning

ARTS-INTEGRATED LEARNING THE FUTURE OF CREATIVE AND JOYFUL PEDAGOGY The NCF 2005 states, ”Aesthetic sensibility and experience being the prime sites of the growing child’s creativity, we must bring the arts squarely into the domain of the curricular, infusing them in all areas of learning while giving them an identity of their own at relevant stages. If we are to retain our unique cultural identity in all its diversity and richness, we need to integrate art education in the formal schooling of our students for helping them to apply art-based enquiry, investigation and exploration, critical thinking and creativity for a deeper understanding of the concepts/topics. This integration broadens the mind of the student and enables her / him to see the multi- disciplinary links between subjects/topics/real life. Art Education will continue to be an integral part of the curriculum, as a co-scholastic area and shall be mandatory for Classes I to X. Please find attached the rich cultural heritage of India and its cultural diversity in a tabular form for reading purpose. The young generation need to be aware of this aspect of our country which will enable them to participate in Heritage Quiz under the aegis of CBSE. TRADITIONAL TRADITIONAL DANCES FAIRS & FESTIVALS ART FORMS STATES & UTS DRESS FOOD (ILLUSTRATIVE) (ILLUSTRATIVE) (ILLUSTRATIVE) (ILLUSTRATIVE) (ILLUSTRATIVE) Kuchipudi, Burrakatha, Tirupati Veerannatyam, Brahmotsavam, Dhoti and kurta Kalamkari painting, Pootha Remus Andhra Butlabommalu, Lumbini Maha Saree, Langa Nirmal Paintings, Gongura Pradesh Dappu, Tappet Gullu, Shivratri, Makar Voni, petticoat, Cherial Pachadi Lambadi, Banalu, Sankranti, Pongal, Lambadies Dhimsa, Kolattam Ugadi Skullcap, which is decorated with Weaving, carpet War dances of laces and fringes. -

![Print This Article [ PDF ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9585/print-this-article-pdf-1589585.webp)

Print This Article [ PDF ]

Orality, Inscription, and the Creation of a New Lore Orality, Inscription …[The] peculiar temporality of folk- and the Creation of a New Lore lore as a disciplinary subject, whether coded in the terminology of survival, archaism, antiquity, and tradition, or Roma Chatterji in the definition of folkloristics as a University of Delhi historical science, has contributed to India the discipline's inability to imagine a truly contemporary, as opposed to a contemporaneous, subject… Folklore is by many (though not all) definitions out of step with the time and the con- Abstract text in which it is found. This essay examines the process by which Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, the discourse of folklore is used to "Folklore's Crisis" 1998, 283 entextualize and recontextualize the oral tra- dition in West Bengal through a discussion of two contemporary Bangla novels. Motifs from folk tales, myths, and popular epic po- n an essay that critically reviews ems are being re-appropriated by urban cul- folklore's disciplinary position vis-à- tural forms– both popular as well as elite – Ivis history and culture, Kirshenblatt- to articulate new identities and subject posi- Gimblett (1998) says that temporal dis- tions. I selected these novels by considering location between the site of origin and the mode in which orality is inscribed and the present location of particular cultural the time period. One of the novels attempts forms signals the presence of folklore. to re-constitute oral lore from a popular epic Kirshenblatt-Gimblett thus conceptual- composed in the medieval period, and the izes culture as heterogeneous, layered other re-inscribes an origin myth that is part and composed of multiple strands that of folk ritual into a new genre via the media- are interconnected in rather haphazard tion of folklore discourse that is responsible and contingent ways. -

A Case Study of Different Folk Cultures of Purulia: a Study of Folk Songs and Dances and the Problems at “Baram” Village, Purulia, West Bengal, India

Reinvention International: An International Journal of Thesis Projects and Dissertation Vol. 1, Issue 1 - 2018 A CASE STUDY OF DIFFERENT FOLK CULTURES OF PURULIA: A STUDY OF FOLK SONGS AND DANCES AND THE PROBLEMS AT “BARAM” VILLAGE, PURULIA, WEST BENGAL, INDIA SANTANU PANDA* CERTIFICATE This is to certify that Santanu Panda has completed his general work for partial fulfilment of M.A 3rd semester bearing Roll- 53310016 No-0046 Session- 2016-2017 of Sidho-Kanho-Birsha-University, carried out his field work at Baram village of Purulia district under supervision of Dr Jatishankar Mondal of Department of English. This is original and basic research work on the topic entitled A Case Study of Different FOLK CULTURES OF Purulia: A study of FOLK SONGS AND DANCES AND THE PROBLEMS AT “BARAM” VILLAGE He is very energetic and laborious fellow as well as a good field worker in Field study. Faculty of the Department of English ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I, Santanu Panda a student of semester III, Department of English, Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University, Purulia, acknowledge all my teachers and guide of the research project who help me to complete this Outreach Program with in time I, acknowledge Dr. Jatishankar Mondal, Assistant Professor, from the core of my heart because without his guidance and encouragement, this work is not possible. I also acknowledge my group members (Raju Mahato, Ramanath Mahato, Nitai Mondal, Nobin Chandra Mahato, Pabitra Kumar and Saddam Hossain) for their participation and the other group also for their support. My sincere thanks also go to the respondents, that is, the villagers, the Chhau club and Jhumur club in Baram for their sincere co-operation during the data collection. -

Study of Tribes and Their Festivals, Folk Culture & Art of Bankura District, West Bengal: a Descriptive Review

International Journal of Education, Modern Management, Applied Science & Social Science (IJEMMASSS) 17 ISSN : 2581-9925, Impact Factor: 6.340, Volume 03, No. 02(IV), April - June, 2021, pp.17-20 STUDY OF TRIBES AND THEIR FESTIVALS, FOLK CULTURE & ART OF BANKURA DISTRICT, WEST BENGAL: A DESCRIPTIVE REVIEW Aparna Misra ABSTRACT Several districts of West Bengal have been well-established on the festivals, cultures, and Folk art from the ancient time. A descriptive review was done after compiling historical perspectives, geographical features, and Folk art & culture of Bankura district, West Bengal, India. Interestingly, it was found that cultural activities and Folk art are closely depending upon historical and geographical features of Bankura district. Moreover, tribals are the most important population where traditional knowledge is transferred to craft technology and they enjoy for producing the craft and paintings with the help of local resources. This review may help the academicians, researchers, media personnel and Government authorities to encourage their technology for their household industrial development. Further research is suggested for the socio-economic benefit related to these folk, festivals, culture, and crafts productions through proper trading. In Indian perspective, still various districts of West Bengal are potential for folk music, dance or art which canbe evocative to the rich Indian culture. Keywords: Tribal Culture, Folk Art, Festival, Local Resources, Natural Resources, Craft and Painting. ________________ Introduction According to Dalton (1872), it was established that Bengal has diverse ethnological importance. Different states of India harbour the indigenous people called as “tribes” and “tribes” regarded as a social establishment have been identified in two traditions mentioned in the report of Gramin Vikas Seva Sanshtha (2013)in which one is found in a stage in the history of evolution of human civilization while other is a society organization based on bonding of association that empowered them to be a multifunctional grouping. -

Socio-Cultural Changes in Rural West Bengal

SOCIO-CULTURAL CHANGES IN RURAL WEST BENGAL by ARILD ENGELSEN RUUD SUBMITTED FOR THE PhD DEGREE LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE Department of Anthropology and Development Studies Institute April 1995 UMI Number: U615B98 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615B98 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT The emergence of broad rural support in West Bengal for the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPM) is here studied through the history (1960 to present) of two villages in Burdwan district. The focus is on the relationship between the dynamics of village politics and political and ideological changes of the larger polity. Village politics constitutes an important realm of informal rules for political action and public participation where popular perceptions of wider political events and cultural changes are created. The communist mobilization of the late 1960s followed from an informal alliance formed between sections of the educated (and politicized) middle-class peasantry and certain groups (castes) of poor. The middle-class peasantry drew inspiration from Bengal’s high-status and literary but radicalized tradition. -

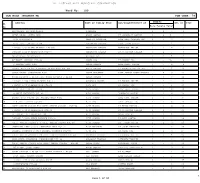

Ward No: 109 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79

BPL LIST-KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Ward No: 109 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Member Sl Address Name of Family Head Son/Daughter/Wife of BPL ID Year No Male Female Total 1 MUKUNDAPUR 100 MUKUNDAPUR A MANDAL 1 2 3 1 2 NITAI NAGAR GREEN PARK ABANI MANDAL LT SANNYASHI MANDAL 6 4 10+ 2 3 2/34 MUKUNDAPUR ABHIJIT ACHARJEE LATE ANIL CHANDRA DAS 2 1 3 3 4 P/13 SOHID SMRITY SADAN ABHIMANNA BAIDYA LATE SHYAM BAIDYA 1 1 2 4 5 D BLOCK D/12 PURBA RAJAPUR D BLOCK ABHIMUNNU HALDER ABHIMUNNU HALDER 2 2 4 5 6 D-BLOCK D/12 PURBARAJAPUR KOL-75 ABHIMUNYA HALDER LT.JUDHISTIR HALDER 3 2 5 6 7 MUKUNDAPUR MUKUNDAPUR ABINASH ROY 3 2 5 7 8 BUDERHAT NAYABAD KOL-99 ADHIR DAS LT.PANCHU DAS 6 5 10+ 8 9 8 NAYABAD MAIN ROAD ADHIR HALDAR LATE BABLU HALDAR 4 5 9 9 10 BIKASH GUHA COLONY 8 NAYABAD MUKUNDAPUR KOL-99 ADHIR HALDAR LT.KANGSHADHAR HALDAR 1 4 5 10 11 GANGA NAGAR GANGANAGAR ROAD ADHIR MAZUMDAR LATE JAMINI KANTA MAZUMDA 5 4 9 11 12 PURBA RAJAPUR D BLOCK D102 PURBA RAJAPUR D BLOCK ADHIR SARDAR 4 4 8 12 13 D-BLOCK D/104 PURBA RAJAPUR KOL-75 ADYABALA HALDER LT.TARANI HALDER 2 3 5 13 14 D BLOCK D/34 PURBARAJAPUR KOL-32 AJAY DAS LT.KARTIK DAS 1 1 2 14 15 N/12 SOHID SMRITY SADAN AJAY HAZRA LATE SUSIL HAZRA 2 4 6 15 16 4 CHHIT KALIKAPUR KOL-99 AJAY MONDAL DHANANJOY MONDAL 2 2 4 16 17 BIKASH GUHA COLONY 101 NAYABAD MAIN ROAD AJAY SARDAR LATE FANI SARDAR 2 3 5 17 18 B/5 SAHID SMIRTY COLONY AJIT DAS LATE SANTOSH DAS 2 4 6 18 19 SAHID SMRITI COLONI F-3 SAHID SMRITI COLONI KOL-94 AJIT HALDAR LT.BHIRU HALDAR 2 2 4 19 20 D BLOCK D/12 PURBARAJAPUR KOL-32 AJIT HALDER LT.JUDHISTIR HALDER 1 2 3 20 21 BUDHERHAT BUDHERHAT KOL-99 AJIT MONDAL GOPAL MONDAL 1 4 5 22 22 D-BLOCK D/136A PURBA RAJAPUR KOL-75 AJIT SARDAR LT.ANIL SARDAR 3 2 5 24 23 SAHID SMRITY COLONY F-3 SAHID SMRITY COLONY KOL-94 AJIT SARDAR LT. -

Final Report Evaluation Study of Tribal/Folk Arts and Culture in West Bengal, Orissa, Jharkhand, Chhatisgrah and Bihar

Final Report Evaluation Study of Tribal/Folk Arts and Culture in West Bengal, Orissa, Jharkhand, Chhatisgrah and Bihar Submitted to SER Division Planning Commission Govt. of India New Delhi Submitted by Gramin Vikas Seva Sanshtha Dist. 24 Parganas (North), West Bengal 700129 INDIA Executive Summary: India is marked by its rich traditional heritage of Tribal/Folk Arts and Culture. Since the days of remote past, the diversified art & cultural forms generated by the tribal and rural people of India, have continued to evince their creative magnificence. Apart from their outstanding brilliance from the perspective of aesthetics , the tribal/folk art and culture forms have played an instrumental role in reinforcing national integrity, crystallizing social solidarity, fortifying communal harmony, intensifying value-system and promoting the elements of humanism among the people of the country. However with the passage of time and advent of globalization, we have witnessed the emergence of a synthetic homogeneous macro-culture. Under the influence of such a voracious all-pervasive macro-culture the diversified heterogeneous tribal/folk culture of our country are suffering from attrition and erosion. Thus the stupendous socio-cultural exclusivity of the multifarious communities at the different nooks and corners of our country are getting endangered. Under such circumstances, the study–group Gramin Vikash Seva Sanstha formulated a project proposal on “Evaluation Study of Tribal/Folk Arts and Culture in West Bengal, Orissa, Jharkhand, Chhatisgrah