Print This Article [ PDF ]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DEPARTMENT of FOLKLORE University of Kalyani

DEPARTMENT OF FOLKLORE University of Kalyani COURSE CURRICULA OF M.A. IN FOLKLORE (Two- years Master’s Degree Programme under the Scheme of CBCS) Session: 2017-2018 and onwards As recommended by the Post Graduate Board of Studies (PGBoS) in Folklore in the meeting held on May 05, 2017 OPERATIONAL ASPECTS A. Timetable: 1) Class-hour will be of 1 hour and the time schedule of classes should be from 10.30 a.m. to 5.00 p.m. with 30 minutes lunch-break during 1.30 to 2.00 p.m., from Monday to Friday. Thus there shall be maximum 6 classes a day. 2) Normal 16 class-hours in a week may be kept for direct class instructions. The remaining 14 hours in a week shall be kept for Tutorial, Dissertation, Seminar, Assignments, Special Classes, holding class-tests etc. as may be required for the course. B. Course-papers and Allocation of Class-Hours per Course: 1) For evaluation purposes, each course shall be of 100 marks and for each course of 100 marks total number of direct instruction hours (theory/practical/field-training) shall be 48 hours. 2) The full course in 4 semesters shall be of total 1600 marks with total 16 courses (Fifteen Core Courses & One Open Course). In each semester, the course work shall be for 4 courses of total 400 marks. C. Credit Specification of the Course Curricula: M.A. Course in Folklore shall comprise 4 semesters. Each semester shall have 4 courses. In all, there shall be 16 courses of 4 credits each. -

Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata∗

Modern Asian Studies: page 1 of 39 C Cambridge University Press 2017 doi:10.1017/S0026749X16000913 REVIEW ARTICLE Goddess in the City: Durga pujas of contemporary Kolkata∗ MANAS RAY Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, India Email: [email protected] Tapati Guha-Thakurta, In the Name of the Goddess: The Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata (Primus Books, Delhi, 2015). The goddess can be recognized by her step. Virgil, The Aeneid,I,405. Introduction Durga puja, or the worship of goddess Durga, is the single most important festival in Bengal’s rich and diverse religious calendar. It is not just that her temples are strewn all over this part of the world. In fact, goddess Kali, with whom she shares a complementary history, is easily more popular in this regard. But as a one-off festivity, Durga puja outstrips anything that happens in Bengali life in terms of pomp, glamour, and popularity. And with huge diasporic populations spread across the world, she is now also a squarely international phenomenon, with her puja being celebrated wherever there are even a score or so of Hindu Bengali families in one place. This is one Bengali festival that has people participating across religions and languages. In that ∗ Acknowledgements: Apart from the two anonymous reviewers who made meticulous suggestions, I would like to thank the following: Sandhya Devesan Nambiar, Richa Gupta, Piya Srinivasan, Kamalika Mukherjee, Ian Hunter, John Frow, Peter Fitzpatrick, Sumanta Banjerjee, Uday Kumar, Regina Ganter, and Sharmila Ray. Thanks are also due to Friso Maecker, director, and Sharmistha Sarkar, programme officer, of the Goethe Institute/Max Mueller Bhavan, Kolkata, for arranging a conversation on the book between Tapati Guha-Thakurta and myself in September 2015. -

Eforms Publication of SEM-VI, 2021 on 7-9-2021.Xlsx

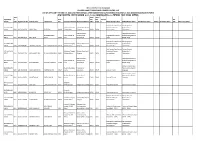

THE UNIVERSITY OF BURDWAN COLLEGE NAME- TARAKESWAR DEGREE COLLEGE- 415 LIST OF APPLICANT FOR SEM -VI, 2020 AND THEIR DETAILS AFTER SUBMITTING BA/BCOM/BSC (H/G) SEM-VI, 2021 ONLINE EXAMINATION FORM (যারা অনলাইন পেম কেরেছ ৯/০৭/২০২১ (বার) রাত ৮.০০ িমিনেটর মেধ তােদর তািলকা) Cours Hons/ Hons/ Application e Hons Gen Gen Gen Sub- SEC Seq No Code Registration No Student Name Father Name Sub Honours Sub CC-13 Honours Sub CC-14 Sub-1 Sub-2 3 DSE-3/1B Topic Name DSE-4/2BTopic Name DSE-3B Topic Name GE Sub GE-2 Topic Name Sub SEC-4 Topic Name Bish Sataker Swadhinata- Sahitya Bisayak 20216415AH0 Sanskrita O Ingreji Sahityer Rup- Riti O Purbabarti Bangla Prabandha O 29030 BAH 201501064828 SRIBAS BAG DILIP BAG BNGH Sahityer Itihas Sangrup BNGH BNGH Kathasahitya Lakasahitya Rabindranath's Stage Demonstration - 20216415AH0 DIPENDRA NATH Khyal Vilambit & Gitinatya and Stage Demonstration - Rabindra Sangeet and 33874 BAH 201501070379 ADITI BERA BERA MUCH Drut Nrityanatya MUCH MUCH Khyal Bengali Song Bish Sataker Swadhinata- Sahitya Bisayak 20216415AH0 Sanskrita O Ingreji Sahityer Rup- Riti O Purbabarti Bangla Prabandha O 28925 BAH 201601067467 CHANDRA SANTRA ASIT KUMAR SANTRA BNGH Sahityer Itihas Sangrup BNGH BNGH Kathasahitya Lakasahitya Bish Sataker Swadhinata- Sahitya Bisayak 20216415AH0 Sanskrita O Ingreji Sahityer Rup- Riti O Purbabarti Bangla Prabandha O 28717 BAH 201601073761 MADHUMITA BALI SHYAMSUNDAR BALI BNGH Sahityer Itihas Sangrup BNGH BNGH Kathasahitya Lakasahitya Rabindranath's Stage Demonstration - 20216415AH0 Khyal Vilambit & Gitinatya and -

Madhusudan Dutt and the Dilemma of the Early Bengali Theatre Dhrupadi

Layered homogeneities: Madhusudan Dutt and the dilemma of the early Bengali theatre Dhrupadi Chattopadhyay Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 5–34 | ISSN 2050-487X | www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk 2016 | The South Asianist 4 (2): 5-34 | pg. 5 Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 5-34 Layered homogeneities: Madhusudan Dutt, and the dilemma of the early Bengali theatre DHRUPADI CHATTOPADHYAY, SNDT University, Mumbai Owing to its colonial tag, Christianity shares an uneasy relationship with literary historiographies of nineteenth-century Bengal: Christianity continues to be treated as a foreign import capable of destabilising the societal matrix. The upper-caste Christian neophytes, often products of the new western education system, took to Christianity to register socio-political dissent. However, given his/her socio-political location, the Christian convert faced a crisis of entitlement: as a convert they faced immediate ostracising from Hindu conservative society, and even as devout western moderns could not partake in the colonizer’s version of selective Christian brotherhood. I argue that Christian convert literature imaginatively uses Hindu mythology as a master-narrative to partake in both these constituencies. This paper turns to the reception aesthetics of an oft forgotten play by Michael Madhusudan Dutt, the father of modern Bengali poetry, to explore the contentious relationship between Christianity and colonial modernity in nineteenth-century Bengal. In particular, Dutt’s deft use of the semantic excess as a result of the overlapping linguistic constituencies of English and Bengali is examined. Further, the paper argues that Dutt consciously situates his text at the crossroads of different receptive constituencies to create what I call ‘layered homogeneities’. -

IJRESS Volume 6, Issue 2

International Journal of Research in Economics and Social Sciences (IJRESS) Available online at: http://euroasiapub.org Vol. 7 Issue 7, July- 2017 ISSN(o): 2249-7382 | Impact Factor: 6.939 | Thomson Reuters Researcher ID: L-5236-2015 Dissemination of social messages by Folk Media – A case study through folk drama Bolan of West Bengal Mr. Sudipta Paul Research Scholar, Department of Mass Communication & Videography, Rabindra Bharati University Abstract: In the vicinity of folk-culture, folk drama is of great significance because it reflects the society by maintaining a non-judgemental stance. It has a strong impact among the audience as the appeal of Bengali folk-drama is undeniable. ‘Bolan’ is a traditional folk drama of Bengal which is mainly celebrated in the month of ‘Chaitra’ (march-april). Geographically, it is prevalent in the mid- northern rural and semi-urban regions of Bengal (Rar Banga area) – mainly in Murshidabad district and some parts of Nadia, Birbhum and Bardwan districts. Although it follows the theatrical procedures, yet it is different from the same because it has no female artists. The male actors impersonate as females and play the part. Like other folk drama ‘Bolan’ is in direct contact with the audience and is often interacted and modified by them. Primarily it narrates mythological themes but now-a-days it narrates contemporary socio-politico-economical and natural issues. As it is performed different contemporary issues of immense interest audiences is deeply integrated with it and try to assimilate the messages of social importance from it. And in this way Mass (traditional) media plays an important role in shaping public opinion and forming a platform of exchange between the administration and the people they serve. -

Hungry Bengal: War, Famine, Riots, and the End of Empire 1939-1946

Hungry Bengal: War, Famine, Riots, and the End of Empire 1939-1946 By Janam Mukherjee A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) In the University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Barbara D. Metcalf, Chair Emeritus Professor David W. Cohen Associate Professor Stuart Kirsch Associate Professor Christi Merrill 1 "Unknown to me the wounds of the famine of 1943, the barbarities of war, the horror of the communal riots of 1946 were impinging on my style and engraving themselves on it, till there came a time when whatever I did, whether it was chiseling a piece of wood, or burning metal with acid to create a gaping hole, or cutting and tearing with no premeditated design, it would throw up innumerable wounds, bodying forth a single theme - the figures of the deprived, the destitute and the abandoned converging on us from all directions. The first chalk marks of famine that had passed from the fingers to engrave themselves on the heart persist indelibly." 2 Somnath Hore 1 Somnath Hore. "The Holocaust." Sculpture. Indian Writing, October 3, 2006. Web (http://indianwriting.blogsome.com/2006/10/03/somnath-hore/) accessed 04/19/2011. 2 Quoted in N. Sarkar, p. 32 © Janam S. Mukherjee 2011 To my father ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank first and foremost my father, Dr. Kalinath Mukherjee, without whom this work would not have been written. This project began, in fact, as a collaborative effort, which is how it also comes to conclusion. His always gentle, thoughtful and brilliant spirit has been guiding this work since his death in May of 2002 - and this is still our work. -

Immigration and Identity Negotiation Within the Bangladeshi Immigrant Community in Toronto, Canada

IMMIGRATION AND IDENTITY NEGOTIATION WITHIN THE BANGLADESHI IMMIGRANT COMMUNITY IN TORONTO, CANADA by RUMEL HALDER A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Anthropology University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba Copyright © 2012 by Rumel Halder ii THE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES ***** COPYRIGHT PERMISSION IMMIGRATION AND IDENTITY NEGOTIATION WITHIN THE BANGLADESHI IMMIGRANT COMMUNITY IN TORONTO, CANADA by RUMEL HALDER A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Copyright © 2012 by Rumel Halder Permission has been granted to the Library of the University of Manitoba to lend or sell copies of this thesis to the Library and Archives Canada (LAC) and to LAC’s agent (UMI/PROQUEST) to microfilm this thesis and to lend or sell copies of the film, and University Microfilms Inc. to publish an abstract of this thesis. This reproduction or copy of this thesis has been made available by authority of the copyright owner solely for the purpose of private study and research, and may only be reproduced and copied as permitted by copyright laws or with express written authorization from the copyright owner. iii Dedicated to my dearest mother and father who showed me dreams and walked with me to face challenges to fulfill them. iv ABSTRACT IMMIGRATION AND IDENTITY NEGOTIATION WITHIN THE BANGLADESHI IMMIGRANT COMMUNITY IN TORONTO, CANADA Bangladeshi Bengali migration to Canada is a response to globalization processes, and a strategy to face the post-independent social, political and economic insecurities in the homeland. -

Department of Music Rabindra Sangeet Hons

Department of Music Rabindra Sangeet Hons. Section Nistarini College, Purulia (Govt. Sponsored and affliated to Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University) Course Outcome The I St paper (101) is Practical. This paper consists of Rabindra Sangeet of 6 Paryas Semester I (I) and some chota kheyals at preliminary level. Students learn the holistic concept of B.A. Hons in Music Rabindra Sangeet in the preliminary level. (Rabindra Sangeet) The 2nd Paper (102) is theoretical. Outline History of Music in Bengal and knowledge of`Raga and Tala GE1 Students of other Hons stream of Sem I and Programme course of Sem V develops foundation of basic knowledge of Rabindi.a Sangeet and chhota kheyal -Practical Paper. Semester 11 The paper 201 is Practical. This paper consists of selected songs based on various B.A. Hons in Music Paryas (]1). (Rabindra Sangeet) The paper 202 is theoretical - general i\'nowledge relating to influence of various songs on Rabindranath's creation. GE2 Students of other Hons stream of Sem 11 and Programme course of Sem Vl develops basic knowledge of selected songs based on various Paryas and knowledge of that ragas. Practical Paper. Two practical papers 301 - selected songs based on various tala coveriiig various Semester 111 Paryas' and types -I. B.A. Hons in Music 302 (Practical) - Selected songs based on various tala covering various Paryas' and types - 11. Paper 303 (Theory) -Knowledge of Ragas, talas and influence of folk (Rabindra Sangeet) songs on Rabindra Sangeet. SEC-1 paper (Theory) -General Aesthetics falls into this category. Semester IV Paper 401 (Practical) -Songs of Rabindranath covering various songs of six Paryas B.A. -

Nobility Or Utility? Zamindars, Businessmen, and Bhadralok As Curators of Theindiannationinsatyajitray’S Jalsaghar ( the Music Room)∗

Modern Asian Studies 52, 2 (2018) pp. 683–715. C Cambridge University Press 2017. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:10.1017/S0026749X16000482 First published online 11 December 2017 Nobility or Utility? Zamindars, businessmen, and bhadralok as curators of theIndiannationinSatyajitRay’s Jalsaghar ( The Music Room)∗ GAUTAM GHOSH The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, China Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract The Bengali bhadralok have had an important impact on Indian nationalism in Bengal and in India more broadly. Their commitment to narratives of national progress has been noted. However, little attention has been given to how ‘earthly paradise’, ‘garden of delights’, and related ideas of refinement and nobility also informed their nationalism. This article excavates the idea of earthly paradise as it is portrayed in Satyajit Ray’s 1958 Bengali film Jalsaghar, usually translated as The Music Room. Jalsaghar is typically taken to depict, broadly, the decadence and decline of aristocratic ‘feudal’ landowners (zamindars) who were granted their holdings and, often, noble rank, such as ‘Lord’ or ‘Raja’, during Mughal or British times, representing the languid past of the nobility, and the ascendance of a ∗ Parts of this article were presented by invitation at the Asian Studies Centre, Oxford University; the South Asian Studies Centre, Heidelberg University, and the Borders, Citizenship and Mobility Workshop at King’s College London. Portions were also presented for the panel ‘Righteous futures: morality, temporality, and prefiguration’ organized by Craig Jeffrey and Assa Doron for the 2016 Australian Anthropological Society Meetings. -

Wedding Videos

P1: IML/IKJ P2: IML/IKJ QC: IML/TKJ T1: IML PB199A-20 Claus/6343F August 21, 2002 16:35 Char Count= 0 WEDDING VIDEOS band, the blaring recorded music of a loudspeaker, the References cries and shrieks of children, and the conversations of Archer, William. 1985. Songs for the bride: wedding rites of adults. rural India. New York: Columbia University Press. Most wedding songs are textually and musically Henry, Edward O. 1988. Chant the names of God: musical cul- repetitive. Lines of text are usually repeated twice, en- ture in Bhojpuri-Speaking India. San Diego: San Diego State abling other women who may not know the song to University Press. join in. The text may also be repeated again and again, Narayan, Kirin. 1986. Birds on a branch: girlfriends and wedding songs in Kangra. Ethos 14: 47–75. each time inserting a different keyword into the same Raheja, Gloria, and Ann Gold. 1994. Listen to the heron’s words: slot. For example, in a slot for relatives, a wedding song reimagining gender and kinship in North India. Berkeley: may be repeated to include father and mother, father’s University of California Press. elder brother and his wife, the father’s younger brother and his wife, the mother’s brother and his wife, paternal KIRIN NARAYAN grandfather and grandmother, brother and sister-in-law, sister and brother-in-law, and so on. Alternately, in a slot for objects, one may hear about the groom’s tinsel WEDDING VIDEOS crown, his shoes, watch, handkerchief, socks, and so on. Wedding videos are fast becoming the most com- Thus, songs can be expanded or contracted, adapting to mon locally produced representation of social life in the performers’ interest or the length of a particular South Asia. -

Conditioning Factors for Fertility Decline in Bengal: History, Language Identity, and Openness to Innovations

Conditioning Factors for Fertility Decline in Bengal: History, Language Identity, and Openness to Innovations ALAKA MALWADE BASU SAJEDA AMIN DECLINES IN FERTILITY in the contemporary world tend to be explained in contemporary terms. Immediate causes are sought and generally center around issues of changing demand and supply. More specifically, the pro- ponents of the importance of changing demand stress the changing struc- tural conditions that alter the costs and benefits of children, while the “sup- ply-siders” give central importance to family planning programs which purportedly increase awareness and practice of contraception so that birth control becomes both desirable and possible. In recent years, these explanations have become enriched by another class of explanations that focus on the spread of positive attitudes toward controlled fertility and toward contraception. These attitudes may arise through means that are only tangentially related to changing economic en- vironments or to government population policy. In particular, they may develop through a process of diffusion of ideas from individuals already posi- tively inclined in this direction. Montgomery and Casterline (1998) provide a clear definition of such diffusion of attitudes in the context of social change: they refer to diffusion as “a process in which individuals’ decisions…are affected by the knowledge, attitudes, and behavior of others with whom they come in contact” (p. 39). These “others” may be of different kinds—peer groups, elites, family, friends, and so on—and the contact may occur in a vari- ety of ways. Montgomery and Casterline (1998) postulate three principal mechanisms for these “social effects”: social learning, social influence, and social norms. -

3Rupture in South Asia

3Rupture in South Asia While the 1950s had seen UNHCR preoccupied with events in Europe and the 1960s with events in Africa following decolonization, the 1970s saw a further expansion of UNHCR’s activities as refugee problems arose in the newly independent states. Although UNHCR had briefly been engaged in assisting Chinese refugees in Hong Kong in the 1950s, it was not until the 1970s that UNHCR became involved in a large-scale relief operation in Asia. In the quarter of a century after the end of the Second World War, virtually all the previously colonized countries of Asia obtained independence. In some states this occurred peacefully,but for others—including Indonesia and to a lesser extent Malaysia and the Philippines—the struggle for independence involved violence. The most dramatic upheaval, however, was on the Indian sub-continent where communal violence resulted in partition and the creation of two separate states—India and Pakistan—in 1947. An estimated 14 million people were displaced at the time, as Muslims in India fled to Pakistan and Hindus in Pakistan fled to India. Similar movements took place on a smaller scale in succeeding years. Inevitably, such a momentous process produced strains and stresses in the newly decolonized states. Many newly independent countries found it difficult to maintain democratic political systems, given the economic problems which they faced, political challenges from the left and the right, and the overarching pressures of the Cold War. In several countries in Asia, the army seized political power in a wave of coups which began a decade or so after independence.