Wedding Videos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Folk and Traditional Media: a Powerful Tool for Rural Development

© Kamla-Raj 2011 J Communication, 2(1): 41-47 (2011) Folk and Traditional Media: A Powerful Tool for Rural Development Manashi Mohanty and Pritishri Parhi* College of Home Science, O.U.A.T, Bhubaneswar 751 003, Orissa, India Telephone: *<9437302802>, *<9437231705>; E-mail: [email protected] KEYWORDS Folk Media. Traditional Media. Rural Development ABSTRACT Tradition is the cumulative heritage of society which permeates through all levels of social organization, social structure and the structure of personality. The tradition which is the cumulative social heritage in the form of habit, custom, attitude and the way of life is transmitted from generation to generation either through written words or words of mouth. It was planned to focus the study on stakeholders of rural development and folk media persons, so that their experience, difficulties, suggestion etc. could be collected to make the study realistic and feasible. The study was conducted in the state of Orissa comprising 30 districts out of which 3 coastal districts, namely, Cuttack, Puri and Balasore were selected according to the specific folk media culture namely, ‘Jatra’, ‘Pattachitra’ , ‘Pala’, ‘Daskathjia’ for their cultural aspects and uses. The study reveals that majority of the respondents felt that folk media is used quite significantly in rural development for its cultural aspect but in the era of Information and Communication Technology (ICT), it is losing its significance. The study supports the idea that folk media can be used effectively along with the electronic media for the sake of the development of rural society INTRODUCTION their willing participation in the development of a country is well recognized form of reaching The complex social system with different people, communicating with them and equipp- castes, classes, creeds and tribes in our country ing them with new skills. -

DEPARTMENT of FOLKLORE University of Kalyani

DEPARTMENT OF FOLKLORE University of Kalyani COURSE CURRICULA OF M.A. IN FOLKLORE (Two- years Master’s Degree Programme under the Scheme of CBCS) Session: 2017-2018 and onwards As recommended by the Post Graduate Board of Studies (PGBoS) in Folklore in the meeting held on May 05, 2017 OPERATIONAL ASPECTS A. Timetable: 1) Class-hour will be of 1 hour and the time schedule of classes should be from 10.30 a.m. to 5.00 p.m. with 30 minutes lunch-break during 1.30 to 2.00 p.m., from Monday to Friday. Thus there shall be maximum 6 classes a day. 2) Normal 16 class-hours in a week may be kept for direct class instructions. The remaining 14 hours in a week shall be kept for Tutorial, Dissertation, Seminar, Assignments, Special Classes, holding class-tests etc. as may be required for the course. B. Course-papers and Allocation of Class-Hours per Course: 1) For evaluation purposes, each course shall be of 100 marks and for each course of 100 marks total number of direct instruction hours (theory/practical/field-training) shall be 48 hours. 2) The full course in 4 semesters shall be of total 1600 marks with total 16 courses (Fifteen Core Courses & One Open Course). In each semester, the course work shall be for 4 courses of total 400 marks. C. Credit Specification of the Course Curricula: M.A. Course in Folklore shall comprise 4 semesters. Each semester shall have 4 courses. In all, there shall be 16 courses of 4 credits each. -

The Bauls of Birbhum: Identity, Fusion and Diffusion Bidhan Mondal M

International Research Journal of Interdisciplinary & Multidisciplinary Studies (IRJIMS) A Peer-Reviewed Monthly Research Journal ISSN: 2394-7969 (Online), ISSN: 2394-7950 (Print) Volume-I, Issue-IX, October 2015, Page No. 06-11 Published by: Scholar Publications, Karimganj, Assam, India, 788711 Website: http://www.irjims.com The Bauls of Birbhum: Identity, Fusion and Diffusion Bidhan Mondal M. Phil Student (UGC Junior Research Fellow), Department of Folklore, University of Kalyani, Kalyani, West Bengal, India Dr. Sujay Kumar Mandal Associate Professor & Head, Dept. of Folklore, University of Kalyani, Kalyani, West Bengal, India Abstract In the political climate of ardent nationalism the pride on a glorious, indigenous past was to be resuscitated through the revaluation and rehabilitation of local folk traditions, that led to my interest in collecting folklore and the increasing use (and misuse) of folk themes. The relationship between folklore and technology is a long debated one. In the earlier phases of folkloristics, technological development was seen as a threat to the conservation of folklife and scholars were busy in collecting and preserving ‘authentic’ tales, songs and handicraft before the homologating assault of modern civilisation destroyed them. This article intends to examine the nexus between folklore and technology in the context of Bengali Baul songs of Birbhum and their Sahajiya Sadhana, from a different perspective from the earlier. It takes interest in discovering the bricolage of humanism, the fusion and diffusion from beyond that helps increasing the “cultural syncretism” through Baul songs that has been delivering the secrets of Indian culture through their performances all over the world, without media and technology this could never be possible. -

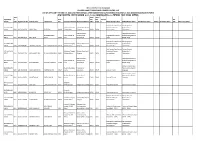

Eforms Publication of SEM-VI, 2021 on 7-9-2021.Xlsx

THE UNIVERSITY OF BURDWAN COLLEGE NAME- TARAKESWAR DEGREE COLLEGE- 415 LIST OF APPLICANT FOR SEM -VI, 2020 AND THEIR DETAILS AFTER SUBMITTING BA/BCOM/BSC (H/G) SEM-VI, 2021 ONLINE EXAMINATION FORM (যারা অনলাইন পেম কেরেছ ৯/০৭/২০২১ (বার) রাত ৮.০০ িমিনেটর মেধ তােদর তািলকা) Cours Hons/ Hons/ Application e Hons Gen Gen Gen Sub- SEC Seq No Code Registration No Student Name Father Name Sub Honours Sub CC-13 Honours Sub CC-14 Sub-1 Sub-2 3 DSE-3/1B Topic Name DSE-4/2BTopic Name DSE-3B Topic Name GE Sub GE-2 Topic Name Sub SEC-4 Topic Name Bish Sataker Swadhinata- Sahitya Bisayak 20216415AH0 Sanskrita O Ingreji Sahityer Rup- Riti O Purbabarti Bangla Prabandha O 29030 BAH 201501064828 SRIBAS BAG DILIP BAG BNGH Sahityer Itihas Sangrup BNGH BNGH Kathasahitya Lakasahitya Rabindranath's Stage Demonstration - 20216415AH0 DIPENDRA NATH Khyal Vilambit & Gitinatya and Stage Demonstration - Rabindra Sangeet and 33874 BAH 201501070379 ADITI BERA BERA MUCH Drut Nrityanatya MUCH MUCH Khyal Bengali Song Bish Sataker Swadhinata- Sahitya Bisayak 20216415AH0 Sanskrita O Ingreji Sahityer Rup- Riti O Purbabarti Bangla Prabandha O 28925 BAH 201601067467 CHANDRA SANTRA ASIT KUMAR SANTRA BNGH Sahityer Itihas Sangrup BNGH BNGH Kathasahitya Lakasahitya Bish Sataker Swadhinata- Sahitya Bisayak 20216415AH0 Sanskrita O Ingreji Sahityer Rup- Riti O Purbabarti Bangla Prabandha O 28717 BAH 201601073761 MADHUMITA BALI SHYAMSUNDAR BALI BNGH Sahityer Itihas Sangrup BNGH BNGH Kathasahitya Lakasahitya Rabindranath's Stage Demonstration - 20216415AH0 Khyal Vilambit & Gitinatya and -

Krishnalila in Terracotta Temples of Bengal

Krishnalila in Terracotta Temples of Bengal Amit Guha Independent Researcher Introduction The brick temples of Bengal are remarkable for the intricately sculpted terracotta panels covering their facades. After an initial period of structural and decorative experimentation in the 17th and 18th centuries, there was some standardization in architecture and embellishment of these temples. However, distinct regional styles remained. From the late 18th century a certain style of richly-decorated temple became common, particularly in the districts of Hugli and Howrah. These temples, usually two- storeyed or atchala and with a triple-arched entrance porch, had carved panels arranged in a fairly well-defined format (Figure 1). Ramayana battle scenes occupied the large panels on the central arch frame with other Ramayana or Krishna stories on the side arches. Running all along the base, including the base of the columns, were two distinctive friezes (Figure 2). Large panels with social, courtly, and hunting scenes ran along the bottom, and above, smaller panels with Krishnalila (stories from Krishna's life). Isolated rectangular panels on the rest of the facade had figures of dancers, musicians, sages, deities, warriors, and couples, within foliate frames. This paper is an iconographic essay on Krishnalila stories in the base panels of the late-medieval terracotta temples of Bengal. The temples of this region are prone to severe damage from the weather, and from rain, flooding, pollution, and renovation. The terracotta panels on most temples are broken, damaged, or completely lost. Exceptions still remain, such as the Raghunatha temple at Parul near Arambagh in Figure 1: Decorated Temple-Facade (Joydeb Kenduli) Hugli, which is unusual in having a well-preserved and nearly-complete series of Krishnalila panels. -

Bengal Patachitra

ojasart.com BENGAL PATACHITRA Ojas is a Sanskrit word which is best transliterated as ‘the nectar of the third eye and an embodiment of the creative energy of the universe’. Ojas endeavours to bring forth the newest ideas in contemporary art. Cover: Swarna Chitrakar Santhal Wedding Ritual, 2018 Vegetable colour on brown paper 28x132 inch 1AQ, Near Qutab Minar Mehrauli, Delhi 110 030 Ph: 85100 44145, +91 11 2664 4145 [email protected] @/#ojasart Bengal Patachitra Works by Anwar Chitrakar 8 Dukhushyam Chitrakar 16 Moyna & Joydeb Chitrakar 24 Swarna Chitrakar 36 Uttam Chitrakar 50 CONTENTS Essays by Ojas Art Award Anubhav R Nath 4 The Mesmerizing Domains of Patta-chittra Prof Neeru Misra 6 Bengal Pata Chitra: Painitng, narrating and singing with twists and turns Prof Soumik Nandy Majumdar 14 Pattachitra of Bengal: An emotion of a community Urmila Banu 34 About the Artists 66 Ojas Art Award rt has a bigger social good is a firm belief and I have seen art at work in changing lives of communities through the economic independence and sustainability that it had Athe potential to provide. A few years ago, I met some accomplished Gond artists in Delhi and really liked their art and the history behind it. Subsequent reading and a visit to Bhopal revealed a lot. The legendary artist J. Swamintahan recognised the importance of the indigenous arts within the contemporary framework, which eventually lead to the establishment and development of institutions like Bharat Bhavan, IGRMS and Tribal Museum. Over the decades, may art forms have been lost to time and it is important to keep the surviving ones alive. -

IJRESS Volume 6, Issue 2

International Journal of Research in Economics and Social Sciences (IJRESS) Available online at: http://euroasiapub.org Vol. 7 Issue 7, July- 2017 ISSN(o): 2249-7382 | Impact Factor: 6.939 | Thomson Reuters Researcher ID: L-5236-2015 Dissemination of social messages by Folk Media – A case study through folk drama Bolan of West Bengal Mr. Sudipta Paul Research Scholar, Department of Mass Communication & Videography, Rabindra Bharati University Abstract: In the vicinity of folk-culture, folk drama is of great significance because it reflects the society by maintaining a non-judgemental stance. It has a strong impact among the audience as the appeal of Bengali folk-drama is undeniable. ‘Bolan’ is a traditional folk drama of Bengal which is mainly celebrated in the month of ‘Chaitra’ (march-april). Geographically, it is prevalent in the mid- northern rural and semi-urban regions of Bengal (Rar Banga area) – mainly in Murshidabad district and some parts of Nadia, Birbhum and Bardwan districts. Although it follows the theatrical procedures, yet it is different from the same because it has no female artists. The male actors impersonate as females and play the part. Like other folk drama ‘Bolan’ is in direct contact with the audience and is often interacted and modified by them. Primarily it narrates mythological themes but now-a-days it narrates contemporary socio-politico-economical and natural issues. As it is performed different contemporary issues of immense interest audiences is deeply integrated with it and try to assimilate the messages of social importance from it. And in this way Mass (traditional) media plays an important role in shaping public opinion and forming a platform of exchange between the administration and the people they serve. -

THE DEVELOPMENT TEAM Principal Investigator Prof. S. P. Bansal Vice

Paper 11: Special Interest Tourism Module 34: Performing Arts of India: Classical Dances, Folk Dance & HistoricalFolk Culture Development of Tourism and Hospitality in the World THE DEVELOPMENT TEAM Principal Investigator Prof. S. P. Bansal Vice Chancellor, Indira Gandhi University, Rewari Co-Principal Investigator Dr. Prashant K. Gautam Director, UIHTM, Panjab University, Chandigarh Paper Coordinator Prof. Deepak Raj Gupta School of Hospitality & Tourism Management (SHTM), Jammu University Content Writer Dr. Arunesh parashar, Chief Coordinator Department Of Tourism Management, Dev Sanskriti University Content Reviewer Prof. Pariskhit Manhas Director , school of hospitality & tourism management Jammu university, Jammu ITEMS DESCRIPTION OF MODULE Subject Name Tourism and Hotel Management Paper Name Special Interest Tourism Module Title Performing Arts of India: Classical Dances, Folk Dances and Folk Culture Module Id 34 Pre- Requisites Basic knowledge about Performing Arts Objectives To develop a basic insight about the performing arts in India Keywords Classical, folks lore, folk dances and folk cultures QUADRANT-I Performing arts are divided into two dimensions of performance: Dance Music Classical dance Bharatnatyam Bharatnatyam originates in Tamil Nadu which is likewise alluded to as artistic yoga and Natya yoga. The name Bharatnatyam is gotten from the word "Bharata’s" and subsequently connected with the Natyashashtra. Though the style of Bharatnatyam is over two thousand years old, the freshness and lavishness of its embodiment has been held even today. The strategy of human development which Bharatnatyam takes after can be followed back to the fifth Century A.D. from sculptural proof. This established move has an entrancing impact as it inspires the artist and the spectator to a larger amount of profound cognizance. -

Department of Music Rabindra Sangeet Hons

Department of Music Rabindra Sangeet Hons. Section Nistarini College, Purulia (Govt. Sponsored and affliated to Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University) Course Outcome The I St paper (101) is Practical. This paper consists of Rabindra Sangeet of 6 Paryas Semester I (I) and some chota kheyals at preliminary level. Students learn the holistic concept of B.A. Hons in Music Rabindra Sangeet in the preliminary level. (Rabindra Sangeet) The 2nd Paper (102) is theoretical. Outline History of Music in Bengal and knowledge of`Raga and Tala GE1 Students of other Hons stream of Sem I and Programme course of Sem V develops foundation of basic knowledge of Rabindi.a Sangeet and chhota kheyal -Practical Paper. Semester 11 The paper 201 is Practical. This paper consists of selected songs based on various B.A. Hons in Music Paryas (]1). (Rabindra Sangeet) The paper 202 is theoretical - general i\'nowledge relating to influence of various songs on Rabindranath's creation. GE2 Students of other Hons stream of Sem 11 and Programme course of Sem Vl develops basic knowledge of selected songs based on various Paryas and knowledge of that ragas. Practical Paper. Two practical papers 301 - selected songs based on various tala coveriiig various Semester 111 Paryas' and types -I. B.A. Hons in Music 302 (Practical) - Selected songs based on various tala covering various Paryas' and types - 11. Paper 303 (Theory) -Knowledge of Ragas, talas and influence of folk (Rabindra Sangeet) songs on Rabindra Sangeet. SEC-1 paper (Theory) -General Aesthetics falls into this category. Semester IV Paper 401 (Practical) -Songs of Rabindranath covering various songs of six Paryas B.A. -

Current Affairs 40 40 MCQ of Computer 52

MONTHLY ISSUE - MAY - 2015 CurrVanik’s ent Affairs Banking | Railway | Insurance | SSC | UPSC | OPSC | PSU A Complete Magazine for all Competitive ExaNEmsW SECTIONS BLUE ECONOMY Vanik’s Page Events of the month 200 Updated MCQs 100 One Liners 40 MCQs on Computers 100 GK for SSC & Railway Leading Institute for Banking, Railway & SSC New P u b l i c a t i o n s Vanik’s Knowledge Garden VANIK'S PAGE Cultural Dances In India Andhra Pradesh Ÿ Ghumra Ÿ Kuchipudi Ÿ Karma Naach Ÿ Kolattam Ÿ Keisabadi Arunachal Pradesh Puducherry Ÿ Bardo Chham Ÿ Garadi Assam Punjab Ÿ Bihu dance Ÿ Bhangra Ÿ Jumur Nach Ÿ Giddha Ÿ Bagurumba Ÿ Malwai Giddha Ÿ Ali Ai Ligang Ÿ Jhumar Chhattisgarh Ÿ Karthi Ÿ Panthi Ÿ Kikkli Ÿ Raut Nacha Ÿ Sammi Ÿ Gaur Maria Dance Ÿ Dandass Gujarat Ÿ Ludi Ÿ Garba Ÿ Jindua Ÿ Padhar Rajasthan Ÿ Raas Ÿ Ghoomar Ÿ Tippani Dance Ÿ Kalbelia Himachal Pradesh Ÿ Bhavai Ÿ Kinnauri Nati Ÿ Tera tali Ÿ Namgen Ÿ Chirami Karnataka Ÿ Gair Ÿ Yakshagana Sikkim Ÿ Bayalata Ÿ Singhi Chham Ÿ Dollu Kunitha Tamil Nadu Ÿ Veeragaase dance Ÿ Bharatanatya Kashmir Ÿ Kamandi or Kaman Pandigai Ÿ Dumhal Ÿ Devarattam Lakshadweep Ÿ Kummi Ÿ Lava Ÿ Kolattam Madhya Pradesh Ÿ Karagattam or Karagam Ÿ Tertal Ÿ Mayil Attam or Peacock dance Ÿ Charkula Ÿ Paampu attam or Snake Dance Ÿ Jawara Ÿ Oyilattam Ÿ Matki Dance Ÿ Puliyattam Ÿ Phulpati Dance Ÿ Poikal Kudirai Attam Ÿ Grida Dance Ÿ Bommalattam Ÿ Maanch Ÿ Theru Koothu Maharashtra Tripura Ÿ Pavri Nach Ÿ Hojagiri Ÿ Lavani West Bengal Manipur Ÿ Gambhira Ÿ Thang Ta Ÿ Kalikapatadi Ÿ Dhol cholom Ÿ Nacnī Mizoram Ÿ Alkap Ÿ Cheraw Dance Ÿ Domni Nagaland Others Ÿ Chang Lo or Sua Lua Ÿ Ghoomar (Rajasthan, Haryana) Odisha Ÿ Koli (Maharashtra and Goa) Ÿ Ghumura Dance Ÿ Padayani (Kerala) Ÿ Ruk Mar Nacha (& Chhau dance) North India Ÿ Goti Pua Ÿ Kathak Ÿ Nacnī Ÿ Odissi Ÿ Danda Nacha Ÿ Baagh Naach or Tiger Dance Ÿ Dalkhai Ÿ Dhap MAGAZINE FOR THE MONTH OF MAY - 2015 VANIK’S MAGAZINE FOR THE MONTH OF MAY - 2015 B – 61 A & B, Saheed Nagar & Plot-1441, Opp. -

Graphic Novels Give a Push to Bengal's Dying Folk Arts

Graphic novels give a push to Bengal’s dying folk arts Three books were published in Bengali and English in 2018 Shiv Sahay Singh Kolkata Pintu, a teenager from Mur- shidabad, is in awe to hear the history of Raibenshe, a folk martial dance from south Bengal, from Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore, while Tito, a boy from Kolkata, is surprised to learn that be- hind the Chhau masks are real people dancing. These children are the characters from graphic no- vels brought out by the West Bengal government, the UN- ESCO and Banglanatk.com, to promote traditional crafts of the State. In a unique in- itiative, three such graphic novels have been published on three different art forms of the State, both in Bengali and English in 2018. The graphic story on the Purulia’s famous Chhau dance is called Experiencing Chhau (Dekhe Elam Chhau) while the book on Rai- benshe is called Raibenshe Rocks (Ajo Aache Rai- benshe). The third publica- tion is on the little known puppetry from Nadia titled The tale of a lost leg ( Hara- no Payer Kissa). Engaging young readers “These graphic novels are Art forms: (Clockwise from top) A page from the graphic novel part of our efforts to pro- on Raibenshe; an inside view from the book on Chhau; a mote cultural industries in compilation of covers of various publications. * BANGLANATK.COM different parts of the State under the project Rural minds so that they become Ranjan Sen, author of these Crafts & Cultural Hubs, aware about folk tradition of publications said. which is supported by De- the State. -

Setting the Stage: a Materialist Semiotic Analysis Of

SETTING THE STAGE: A MATERIALIST SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF CONTEMPORARY BENGALI GROUP THEATRE FROM KOLKATA, INDIA by ARNAB BANERJI (Under the Direction of Farley Richmond) ABSTRACT This dissertation studies select performance examples from various group theatre companies in Kolkata, India during a fieldwork conducted in Kolkata between August 2012 and July 2013 using the materialist semiotic performance analysis. Research into Bengali group theatre has overlooked the effect of the conditions of production and reception on meaning making in theatre. Extant research focuses on the history of the group theatre, individuals, groups, and the socially conscious and political nature of this theatre. The unique nature of this theatre culture (or any other theatre culture) can only be understood fully if the conditions within which such theatre is produced and received studied along with the performance event itself. This dissertation is an attempt to fill this lacuna in Bengali group theatre scholarship. Materialist semiotic performance analysis serves as the theoretical framework for this study. The materialist semiotic performance analysis is a theoretical tool that examines the theatre event by locating it within definite material conditions of production and reception like organization, funding, training, availability of spaces and the public discourse on theatre. The data presented in this dissertation was gathered in Kolkata using: auto-ethnography, participant observation, sample survey, and archival research. The conditions of production and reception are each examined and presented in isolation followed by case studies. The case studies bring the elements studied in the preceding section together to demonstrate how they function together in a performance event. The studies represent the vast array of theatre in Kolkata and allow the findings from the second part of the dissertation to be tested across a variety of conditions of production and reception.