Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Freedom in West Bengal Revised

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington Freedom and its Enemies: Politics of Transition in West Bengal, 1947-1949 * Sekhar Bandyopadhyay Victoria University of Wellington I The fiftieth anniversary of Indian independence became an occasion for the publication of a huge body of literature on post-colonial India. Understandably, the discussion of 1947 in this literature is largely focussed on Partition—its memories and its long-term effects on the nation. 1 Earlier studies on Partition looked at the ‘event’ as a part of the grand narrative of the formation of two nation-states in the subcontinent; but in recent times the historians’ gaze has shifted to what Gyanendra Pandey has described as ‘a history of the lives and experiences of the people who lived through that time’. 2 So far as Bengal is concerned, such experiences have been analysed in two subsets, i.e., the experience of the borderland, and the experience of the refugees. As the surgical knife of Sir Cyril Ratcliffe was hastily and erratically drawn across Bengal, it created an international boundary that was seriously flawed and which brutally disrupted the life and livelihood of hundreds of thousands of Bengalis, many of whom suddenly found themselves living in what they conceived of as ‘enemy’ territory. Even those who ended up on the ‘right’ side of the border, like the Hindus in Murshidabad and Nadia, were apprehensive that they might be sacrificed and exchanged for the Hindus in Khulna who were caught up on the wrong side and vehemently demanded to cross over. -

Sri Shivabalayogi Text Formatted

SRI SHIVABALAYOGI by Prof. S. K. Ramachandra Rao FIRST EDITION – 1968 (Publishing Rights Reserved) Price Re. 1=00 Printed by G. Srinivasan, Proprietor Orient Power Press. 54, Lal Bagh Road, Bangalore -27 Table of Contents Foreword........................................................................................................................................................1 THE LIFE ......................................................................................................................................................2 Early Life...............................................................................................................................................2 Poverty...................................................................................................................................................3 The Touch..............................................................................................................................................4 Tapoleela..............................................................................................................................................11 Dhyanayogi..........................................................................................................................................12 IMPORTANT EVENTS IN THE YOGI’S LIFE........................................................................................14 THE TAPOLEELA .....................................................................................................................................15 -

Name of the Element: Durga Puja in West Bengal

IGNCA INVENTORY ON THE INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE Edited and Maintained by Prof. Molly Kaushal Janapada Sampada Division IGNCA Name of the element: Durga Puja in West Bengal. Community: Bengalis of all religious denominations residing in the state of West Bengal. Region: Durga Puja is celebrated not only in West Bengal but in other regions such as Bihar (Biharis), Odisha (Oriyas) and Assam (Ahomiyas) as well as in other states of India where Bengali community reside. Bengali migrants residing in Europe, America and Australia also celebrate this festival. Brief Description: Durga Puja is the most important socio-cultural and religious event in the Bengali festival calendar, celebrated in autumn. The festival is to propitiate the Goddess Durga for her blessings as also celebrate her victory over the demon Mahishasur. It is also believed that Lord Rama had worshipped the goddess Durga to seek divine blessings before undertaking the battle against Ravana. Durga Puja is a ten-day festival, usually in October, which starts from Mahalaya, the inaugural day of the event. Mahalaya is celebrated by Agomoni or songs of welcome. Festivities start five days later with the observance of Shashti, Shaptami, Ashtami, and Nabami. An elaborate community bhog or food-offerings to the Goddess, is prepared and then partaken by congregations on each day of the festivities. On the tenth day, or Bijoya Dashami, the goddess is borne away to the sounds of the dhak, or traditional drum for immersion in nearby rivers or water bodies. The puja mandap or the main altar is essentially a platform inside a makeshift bamboo structure called a pandal. -

Shuktara October 2014 the Major Festival of Durga Puja Is Now Over

shuktara a new home in the world for young adults 43b/5 Narayan Roy Road P.S. Thakurpukur Kolkata 700008 West Bengal INDIA Contact no: - 91 33 2496 0051 October 2014 The major festival of Durga Puja is now over and by the time you read this, Diwali will also have come and gone. Diwali is celebrated in most of India, but here in West Bengal we celebrate Kali Puja. This is the night when Bengalis let off their fireworks, light candles and an evening that everyone at shuktara really enjoys. Because Diwali is usually the following day, they use this excuse and have two nights of fireworks! However this year, both festivals fall on the same day – but I expect they will keep some fireworks back anyway and celebrate for a couple of nights running. As with the Pujas, I usually hide away somewhere quietly! The Durga Puja festivities were enjoyed by everyone at shuktara. Some of the older boys went out on their own, some stayed at home and some of them went with Pappu to help carry Prity and our new girl Moni around the city. They always hire a big car for this occasion and stay out all night long. Sanjay Sarkar – Durga Puja 2014 Moni on 10th September 2014 Moni had come a short time before the Pujas and was very excited to have new clothes and jewellery to wear for her very first outing. At the beginning of September, Pappu had received a phone call from Childline India Foundation about a little girl who they were unable to care for. -

47 Apart from Diwali1 and Durga Puja,2 Few Hindu Religious Festivals

“CHILDREN HAVE THEIR OWN WORLD OF BEING”: AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF CHILDREN’S ACTIVITIES ON THE DAY OF SARASWATI PUJA SEMONTEE MITRA Apart from Diwali1 and Durga Puja,2 few Hindu religious festivals are organized and celebrated publicly in the United States. Saraswati Puja is one such festival. Saraswati Puja, also known as Vasant Panchami, is a Hindu festival celebrated in early February to mark the onset of spring. On this day, Hindus, especially Bengalis,3 worship the goddess Saraswati, the Vedic goddess of knowledge and wisdom, music, arts, and science. She is also the companion of Lord Brahma who, with her knowledge and wisdom, created the universe. Bengalis consider participation in this puja4 compulsory for students, scholars, and creative artists. Therefore, Indian American Bengali parents force their children to participate in this festival, whereas they might be lax on other religious occasions. As a participant-observer of this recent Indian festival in Central Pennsylvania, United States, I found that the cultural scene—the collective, communal celebration of Saraswati Puja—was not as simple as children of foreign-born parents following a transplanted tradition and gaining ethnic identity. On the contrary, I noticed that Indian American Bengali children typically indulged in activities such as games that are not traditionally part of the religious observance in India. Their interactions, both in and out of the social frame of a religious ritual, especially Saraswati Puja, reveal that in America the festive day has taken on the function -

Immigration and Identity Negotiation Within the Bangladeshi Immigrant Community in Toronto, Canada

IMMIGRATION AND IDENTITY NEGOTIATION WITHIN THE BANGLADESHI IMMIGRANT COMMUNITY IN TORONTO, CANADA by RUMEL HALDER A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Anthropology University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba Copyright © 2012 by Rumel Halder ii THE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES ***** COPYRIGHT PERMISSION IMMIGRATION AND IDENTITY NEGOTIATION WITHIN THE BANGLADESHI IMMIGRANT COMMUNITY IN TORONTO, CANADA by RUMEL HALDER A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Copyright © 2012 by Rumel Halder Permission has been granted to the Library of the University of Manitoba to lend or sell copies of this thesis to the Library and Archives Canada (LAC) and to LAC’s agent (UMI/PROQUEST) to microfilm this thesis and to lend or sell copies of the film, and University Microfilms Inc. to publish an abstract of this thesis. This reproduction or copy of this thesis has been made available by authority of the copyright owner solely for the purpose of private study and research, and may only be reproduced and copied as permitted by copyright laws or with express written authorization from the copyright owner. iii Dedicated to my dearest mother and father who showed me dreams and walked with me to face challenges to fulfill them. iv ABSTRACT IMMIGRATION AND IDENTITY NEGOTIATION WITHIN THE BANGLADESHI IMMIGRANT COMMUNITY IN TORONTO, CANADA Bangladeshi Bengali migration to Canada is a response to globalization processes, and a strategy to face the post-independent social, political and economic insecurities in the homeland. -

In Conversation with Sanjukta Dasgupta

In Conversation with Sanjukta Dasgupta Jaydeep Sarangi and Antara Ghatak Sanjukta Dasgupta, Professor and Former Head, Dept of English and Ex- Dean, Faculty of Arts, Calcutta University, teaches English and American literature along with New Literatures in English. She is a poet, critic and translator, and her articles, poems, short stories and translations have been published in journals of distinction in India and abroad. Her inner sphere overlaps the outer on the speculative and the shadowy. There is a sublime inwardness in her poems. Her recent signal books include Snapshots, Dilemma, First Language, More Light, and Lakshmi Unbound. She co-authored Radical Rabindranath: Nation, Family, Gender: Post-colonial Readings of Tagore’s Fiction and Film, and she is the Managing Editor of Families: A Journal of Representations. She has received many grants and awards, including Fulbright fellowships and residencies and an Australia India Council Fellowship. Now she is the Convener, English Board, Shaitya Akademi. Professor Dasgupta has visited Nepal and Bangladesh as a member of the SAARC Writers Delegation, and has served as a co-judge and Chairperson for the Commonwealth Writers Prize (Eurasia region). She has visited Melbourne and Malta to serve on the pan- Commonwealth jury panel. She is now an e-member of the advisory committee of the Commonwealth Writers Prize, UK. She is Visiting Professor, Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland, and she is the President of the Executive Committee, Intercultural Poetry and Performance Library in Kolkata. The interview was conducted via email in December 2018. Q: When did you start writing poems and short stories? In Conversation with Sanjukta Dasgupta. -

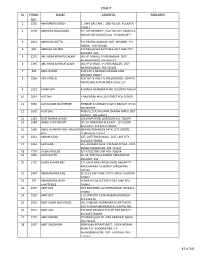

Sl Form No. Name Address Remarks

STARLIT SL FORM NAME ADDRESS REMARKS NO. 1 2235 ABHIMANYU SINGH 2, UMA DAS LANE , 2ND FLOOR , KOLKATA- 700013 2 1998 ABHISHEK MAJUMDER R.P. APPARTMENT , FLAT NO-303 PRAFULLA KANAN (W) KOLKATA-101 P.S-BAGUIATI 3 1922 ABHRANIL DUTTA P.O-PRAFULLANAGAR DIST-24PGS(N) , P.S- HABRA , PIN-743268 4 860 ABINASH HALDER 139 BELGACHIA EAST HB-6 SALT LAKE CITY KOLKATA -106 5 2271 ABU HENA MONIRUL ALAM VILL+P.O-MILKI, P.S-REJINAGAR DIST- MURSHIDABAD, PIN-742163 6 1395 ABU HENA SAHINUR ALAM VILL+P.O-MILKI , P.S-REGINAGAR , DIST- MURSHIDABAD, PIN-742163 7 446 ABUL HASAN B 32 1AH 3 MIAJAN OSTAGAR LANE KOLKATA 700017 8 3286 ADA AFREEN FLAT NO 9I PINES IV GREENWOOD SONATA NEWTOWN ACTION AREA II KOL 157 9 1623 ADHIR GIRI 8 DURGA CHANDRA ROAD KOLKATA 700014 10 2807 AJIT DAS 6 RAJENDRA MULLICK STREET KOL-700007 11 3650 AJIT KUMAR MUKHERJEE SHIBBARI K,S ROAD P.O &P.S NAIHATI DT 24 PGS NORTH 12 1602 AJOY DAS PO&VILL SOUTH GARIA CHARAK MATH DIST 24 PGS S PIN 743613 13 1261 AJOY KUMAR GHOSH 326 JAWPUR RD. DUMDUM KOL-700074 14 1584 AKASH CHOUDHURY DD-19, NARAYANTALA EAST , 1ST FLOOR BAGUIATI , KOLKATA-700059 15 2460 AKHIL CHANDRA ROY MNJUSRI 68 RANI RASHMONI PATH CITY CENTRE ROY DURGAPUR 713216 16 2311 AKRAM AZAD 227, DUTTABAD ROAD, SALT LAKE CITY , KOLKATA-700064 17 1441 ALIP JANA VILL-KHAMAR CHAK P.O-NILKUNTHIA , DIST- PURBA MIDNAPORE PIN-721627 18 2797 ALISHA BEGUM 5/2 B DOCTOR LANE KOL-700014 19 1956 ALOK DUTTA AC-64, PRAFULLA KANAN KRISHNAPUR KOLKATA -101 20 1719 ALOKE KUMAR DEY 271 SASHI BABU ROAD SAHID NAGAR PO KANCHAPARA PS BIZPUR 24PGSN PIN 743145 21 3447 -

Amar Durga Bengali Poem Download

Amar durga bengali poem download CLICK TO DOWNLOAD Konya Slok (Amar Durga) a popular Poem Of mallika renuzap.podarokideal.ru's all About Woman Of 20 century.. in this poem woman power is like a drurga renuzap.podarokideal.ru power of p Woman Power Durga Powerful Women God Movie Posters Movies I Love You Films Dios. More information Saved by it'my life. 3. People also love these ideas. Bengal Iris The Voice Flow Songs Movie Posters Movies Beautiful Films. Arko . Oporadhi Bangladeshi song lyrics and download May 13, Tor Moner Pinjiray Lyrics (তার মেনর িপিরায়) Jisan Khan Shuvo Song October 14, Bengali poem in bengali fonts Ekanto byaktigoto (একা বিগত) September 03, Dedicate these Very romantic Poems to your girlfriend, we need words to express our love and affection and bengali Love poems or choto premer kobita are the best things that you can give to your beloved wife or girlfriend. Bengali or Bangla is one of the sweetest languages in the world. Bangla loves poems Kobita, and Bangla Shayari by nature becomes very heart-charming. 30/07/ · Bangla Lyrics, Bengali Song Lyrics, Bengali Poem, Bangla Kobita, Bangla Song Lyrics, Bengali Love Poem, Bengali Poem Collection. Bengali Lyrics Header Ads Home; Request A Song; Artist Collection; _Anindya Chatterjee; _Arijit Singh; _Anupam Roy; _Lagnajita Chakraborty; _Rupankar Bagchi; _Shreya Ghoshal; Bengali Love Poem; Durga Puja Song; Bengali sad poem; Valentines . Bengali poetry anthology. Dui Banglar Meyeder Shreshtha kabita, Upasana, Kolkata, ; References. External links. Mallika Sengupta and the Poetry of Feminist Conviction. (4 bilingual poems) The unsevered tongue: modern poetry by Bengali women, tr. -

People Without History

People Without History Seabrook T02250 00 pre 1 24/12/2010 10:45 Seabrook T02250 00 pre 2 24/12/2010 10:45 People Without History India’s Muslim Ghettos Jeremy Seabrook and Imran Ahmed Siddiqui Seabrook T02250 00 pre 3 24/12/2010 10:45 First published 2011 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010 www.plutobooks.com Distributed in the United States of America exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010 Copyright © Jeremy Seabrook and Imran Ahmed Siddiqui 2011 The right of Jeremy Seabrook and Imran Ahmed Siddiqui to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 3114 0 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 3113 3 Paperback Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data applied for This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Designed and produced for Pluto Press by Chase Publishing Services Ltd, 33 Livonia Road, Sidmouth, EX10 9JB, England Typeset from disk by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Simultaneously printed digitally by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham, UK and Edwards Bros in the USA Seabrook T02250 00 pre 4 24/12/2010 10:45 Contents Acknowledgements vi Introduction 1 1. -

BUS ROUTE-18-19 Updated Time.Xls LIST of DROP ROUTES & STOPPAGES TIMINGS LIST of DROP ROUTES & STOPPAGES TIMINGS

LIST OF DROP ROUTES & STOPPAGES TIMINGS LIST OF DROP ROUTES & STOPPAGES TIMINGS FOR THE SESSION 2018-19 FOR THE SESSION 2018-19 ESTIMATED TIMING MAY CHANGE SUBJECT ESTIMATED TIMING MAY CHANGE SUBJECT TO TO CONDITION OF THE ROAD CONDITION OF THE ROAD ROUTE NO - 1 ROUTE NO - 2 SL NO. LIST OF DROP STOPPAGES TIMINGS SL NO. LIST OF DROP STOPPAGES TIMINGS 1 DUMDUM CENTRAL JAIL 13.00 1 IDEAL RESIDENCY 13.05 2 CLIVE HOUSE, MALL ROAD 13.03 2 KANKURGACHI MORE 13.07 3 KAJI PARA 13.05 3 MANICKTALA RAIL BRIDGE 13.08 4 MOTI JEEL 13.07 4 BAGMARI BAZAR 13.10 5 PRIVATE ROAD 13.09 5 MANICKTALA P.S. 13.12 6 CHATAKAL DUMDUM ROAD 13.11 6 MANICKTALA DINENDRA STREET XING 13.14 7 HANUMAN MANDIR 13.13 7 MANICKTALA BLOOD BANK 13.15 8 DUMDUM PHARI 01:15 8 GIRISH PARK METRO STATION 13.20 9 DUMDUM STATION 01:17 9 SOVABAZAR METRO STATION 13.23 10 7 TANK, DUMDUM RD 01:20 10 B.K.PAUL AVENUE 13.25 11 AHIRITALA SITALA MANDIR 13.27 12 JORABAGAN PARK 13.28 13 MALAPARA 13.30 14 GANESH TALKIES 13.32 15 RAM MANDIR 13.34 16 MAHAJATI SADAN 13.37 17 CENTRAL AVENUE RABINDRA BHARATI 13.38 18 M.G.ROAD - C.R.AVENUE XING 13.40 19 MOHD.ALI PARK 13.42 20 MEDICAL COLLEGE 13.44 21 BOWBAZAR XING 13.46 22 INDIAN AIRLINES 13.48 23 HIND CINEMA XING 13.50 24 LEE MEMORIAL SCHOOL - LENIN SR. 13.51 ROUTE NO - 3 ROUTE NO - 04 SL NO. -

3Rupture in South Asia

3Rupture in South Asia While the 1950s had seen UNHCR preoccupied with events in Europe and the 1960s with events in Africa following decolonization, the 1970s saw a further expansion of UNHCR’s activities as refugee problems arose in the newly independent states. Although UNHCR had briefly been engaged in assisting Chinese refugees in Hong Kong in the 1950s, it was not until the 1970s that UNHCR became involved in a large-scale relief operation in Asia. In the quarter of a century after the end of the Second World War, virtually all the previously colonized countries of Asia obtained independence. In some states this occurred peacefully,but for others—including Indonesia and to a lesser extent Malaysia and the Philippines—the struggle for independence involved violence. The most dramatic upheaval, however, was on the Indian sub-continent where communal violence resulted in partition and the creation of two separate states—India and Pakistan—in 1947. An estimated 14 million people were displaced at the time, as Muslims in India fled to Pakistan and Hindus in Pakistan fled to India. Similar movements took place on a smaller scale in succeeding years. Inevitably, such a momentous process produced strains and stresses in the newly decolonized states. Many newly independent countries found it difficult to maintain democratic political systems, given the economic problems which they faced, political challenges from the left and the right, and the overarching pressures of the Cold War. In several countries in Asia, the army seized political power in a wave of coups which began a decade or so after independence.