Socio-Cultural Changes in Rural West Bengal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GIPE-012270-Contents.Pdf

SELECTIONS FROM OFFICIAL LETTERS AND DOCUMENTS RELATING TO THE UfE OF RAJA RAMMOHUN ROY VOL. I EDITED BY lW BAHADUR RAMAPRASAD CHANDA, F.R.A.S.B. L.u Supmnteml.nt of lhe ArchteO!ogit:..S Section. lnd;.n MMe~~m, CUct<lt.t. AND )ATINDRA KUMAR MAJUMDAR, M.A., Ph.D. (LoNDON), Of the Middk Temple, 11uris~er-M-Ltw, ddfJOcote, High Court, C41Cflll4 Sometime Professor of Pb.Josophy. Presidency College, C..Scutt.t. With an Introductory Memoir CALCUTIA ORIENTAL BOOK AGENCY 9> PANCHANAN GHOSE LANE, CALCUTTA Published in 1938 Printed and Published by J. C. Sarkhel, at the Calcutta Oriental Press Ltd., 9, Pancb&nan Ghose Lane, Calcutta. r---~-----~-,- 1 I I I I I l --- ---·~-- ---' -- ____j [By courtesy of Rammohun Centenary Committee] PREFACE By his refor~J~ing activities Raja Rammohun Roy made many enemies among the orthodox Hindus as well as orthodox Christians. Some of his orthodox countrymen, not satis· fied with meeting his arguments with arguments, went to the length of spreading calumnies against him regarding his cha· racter and integrity. These calumnies found their way into the works of som~ of his Indian biographers. Miss S, D. Collet has, however, very ably defended the charact~ of the Raja against these calumniet! in her work, "The Life and Letters of Raja Rammohun Roy." But recently documents in the archives of the Governments of Bengal and India as well as of the Calcutta High Court were laid under contribution to support some of these calumnies. These activities reached their climax when on the eve of the centenary celebration of the death of Raja Rammohun Roy on the 27th September, 1933, short extracts were published from the Bill of Complaint of a auit brought against him in the Supreme Court by his nephew Govindaprasad Roy to prove his alleged iniquities. -

View Entire Book

ODISHA REVIEW VOL. LXXI NO. 5 DECEMBER - 2014 MADHUSUDAN PADHI, I.A.S. Commissioner-cum-Secretary RANJIT KUMAR MOHANTY, O.A.S, ( SAG) Director DR. LENIN MOHANTY Editor Editorial Assistance Production Assistance Bibhu Chandra Mishra Debasis Pattnaik Bikram Maharana Sadhana Mishra Cover Design & Illustration D.T.P. & Design Manas Ranjan Nayak Hemanta Kumar Sahoo Photo Raju Singh Manoranjan Mohanty The Odisha Review aims at disseminating knowledge and information concerning Odisha’s socio-economic development, art and culture. Views, records, statistics and information published in the Odisha Review are not necessarily those of the Government of Odisha. Published by Information & Public Relations Department, Government of Odisha, Bhubaneswar - 751001 and Printed at Odisha Government Press, Cuttack - 753010. For subscription and trade inquiry, please contact : Manager, Publications, Information & Public Relations Department, Loksampark Bhawan, Bhubaneswar - 751001. Five Rupees / Copy E-mail : [email protected] Visit : http://odisha.gov.in Contact : 9937057528(M) CONTENTS Shrikshetra, Matha and its Impact Subhashree Mishra ... 1 Good Governance ... 3 India International Trade Fair - 2014 : An Overview Smita Kar ... 7 Mo Kahani' - The Memoir of Kunja Behari Dash : A Portrait Gallery of Pre-modern Rural Odisha Dr. Shruti Das ... 10 Protection of Fragile Ozone Layer of Earth Dr. Manas Ranjan Senapati ... 17 Child Labour : A Social Evil Dr. Bijoylaxmi Das ... 19 Reflections on Mahatma Gandhi's Life and Vision Dr. Brahmananda Satapathy ... 24 Christmas in Eternal Solitude Sonril Mohanty ... 27 Dr. B.R. Ambedkar : The Messiah of Downtrodden Rabindra Kumar Behuria ... 28 Untouchable - An Antediluvian Aspersion on Indian Social Stratification Dr. Narayan Panda ... 31 Kalinga, Kalinga and Kalinga Bijoyini Mohanty .. -

Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-Kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L

Western Washington University Western CEDAR A Collection of Open Access Books and Books and Monographs Monographs 2008 Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L. Curley Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks Part of the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Curley, David L., "Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal" (2008). A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs. 5. https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Books and Monographs at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents Acknowledgements. 1. A Historian’s Introduction to Reading Mangal-Kabya. 2. Kings and Commerce on an Agrarian Frontier: Kalketu’s Story in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 3. Marriage, Honor, Agency, and Trials by Ordeal: Women’s Gender Roles in Candimangal. 4. ‘Tribute Exchange’ and the Liminality of Foreign Merchants in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 5. ‘Voluntary’ Relationships and Royal Gifts of Pan in Mughal Bengal. 6. Maharaja Krsnacandra, Hinduism and Kingship in the Contact Zone of Bengal. 7. Lost Meanings and New Stories: Candimangal after British Dominance. Index. Acknowledgements This collection of essays was made possible by the wonderful, multidisciplinary education in history and literature which I received at the University of Chicago. It is a pleasure to thank my living teachers, Herman Sinaiko, Ronald B. -

Red Bengal's Rise and Fall

kheya bag RED BENGAL’S RISE AND FALL he ouster of West Bengal’s Communist government after 34 years in power is no less of a watershed for having been widely predicted. For more than a generation the Party had shaped the culture, economy and society of one of the most Tpopulous provinces in India—91 million strong—and won massive majorities in the state assembly in seven consecutive elections. West Bengal had also provided the bulk of the Communist Party of India– Marxist (cpm) deputies to India’s parliament, the Lok Sabha; in the mid-90s its Chief Minister, Jyoti Basu, had been spoken of as the pos- sible Prime Minister of a centre-left coalition. The cpm’s fall from power also therefore suggests a change in the equation of Indian politics at the national level. But this cannot simply be read as a shift to the right. West Bengal has seen a high degree of popular mobilization against the cpm’s Beijing-style land grabs over the past decade. Though her origins lie in the state’s deeply conservative Congress Party, the challenger Mamata Banerjee based her campaign on an appeal to those dispossessed and alienated by the cpm’s breakneck capitalist-development policies, not least the party’s notoriously brutal treatment of poor peasants at Singur and Nandigram, and was herself accused by the Communists of being soft on the Maoists. The changing of the guard at Writers’ Building, the seat of the state gov- ernment in Calcutta, therefore raises a series of questions. First, why West Bengal? That is, how is it that the cpm succeeded in establishing -

Abdul En Bangladés Aguri En Bangladés Ahmadi En Bangladés

Ore por los No-Alcanzados Ore por los No-Alcanzados Abdul en Bangladés Aguri en Bangladés País: Bangladés País: Bangladés Etnia: Abdul Etnia: Aguri Población: 27,000 Población: 1,000 Población Mundial: 63,000 Población Mundial: 515,000 Idioma Principal: Bengali Idioma Principal: Bengali Religión Principal: Islam Religión Principal: Hinduismo Estatus: Menos Alcanzado Estatus: Menos Alcanzado Seguidores de Cristo: Pocos, menos del 2% Seguidores de Cristo: Pocos, menos del 2% Biblia: Biblia Biblia: Biblia www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net "Proclamen su gloria entre las naciones" Salmos 96:3 "Proclamen su gloria entre las naciones" Salmos 96:3 Ore por los No-Alcanzados Ore por los No-Alcanzados Ahmadi en Bangladés Akhandji en Bangladés País: Bangladés País: Bangladés Etnia: Ahmadi Etnia: Akhandji Población: 2,100 Población: 500 Población Mundial: 167,000 Población Mundial: 500 Idioma Principal: Bengali Idioma Principal: Bengali Religión Principal: Islam Religión Principal: Islam Estatus: Menos Alcanzado Estatus: Menos Alcanzado Seguidores de Cristo: Pocos, menos del 2% Seguidores de Cristo: Pocos, menos del 2% Biblia: Biblia Biblia: Biblia www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net "Proclamen su gloria entre las naciones" Salmos 96:3 "Proclamen su gloria entre las naciones" Salmos 96:3 Ore por los No-Alcanzados Ore por los No-Alcanzados Ansari en Bangladés Arakanés en Bangladés País: Bangladés País: Bangladés Etnia: Ansari Etnia: Arakanés Población: 1,241,000 Población: 195,000 Población Mundial: 16,505,000 Población Mundial: 241,000 -

DEPARTMENT of FOLKLORE University of Kalyani

DEPARTMENT OF FOLKLORE University of Kalyani COURSE CURRICULA OF M.A. IN FOLKLORE (Two- years Master’s Degree Programme under the Scheme of CBCS) Session: 2017-2018 and onwards As recommended by the Post Graduate Board of Studies (PGBoS) in Folklore in the meeting held on May 05, 2017 OPERATIONAL ASPECTS A. Timetable: 1) Class-hour will be of 1 hour and the time schedule of classes should be from 10.30 a.m. to 5.00 p.m. with 30 minutes lunch-break during 1.30 to 2.00 p.m., from Monday to Friday. Thus there shall be maximum 6 classes a day. 2) Normal 16 class-hours in a week may be kept for direct class instructions. The remaining 14 hours in a week shall be kept for Tutorial, Dissertation, Seminar, Assignments, Special Classes, holding class-tests etc. as may be required for the course. B. Course-papers and Allocation of Class-Hours per Course: 1) For evaluation purposes, each course shall be of 100 marks and for each course of 100 marks total number of direct instruction hours (theory/practical/field-training) shall be 48 hours. 2) The full course in 4 semesters shall be of total 1600 marks with total 16 courses (Fifteen Core Courses & One Open Course). In each semester, the course work shall be for 4 courses of total 400 marks. C. Credit Specification of the Course Curricula: M.A. Course in Folklore shall comprise 4 semesters. Each semester shall have 4 courses. In all, there shall be 16 courses of 4 credits each. -

Fourteenth Session of the Fourieenth Kerala Legislative Assembly

' rounrgsxtll KBRALA l,iletsnrryE ASSEUBLY .l I :. RESUII3 - OF . a$uwss TRANSASTBD DUB$*G Kcratr l*gislatute Sccretariat 2019 .a Kfn CLt' MY,aMASAfitA fRSfr|}{G PRESS' Eq{F,rr."riti$ *, ;,dtiri{4{f*!t5ffii{rE!*'' FOURTEENTH KERALA LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY RESUME OF BUSINESS TRANSACTED DURING THE FOLTRTEENTH SESSION 651t2019 FOURTEtsNTH SESSION FOURTEENTH KERALA LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Fourtcenth Session Date of Commencement January 25,2019 Date of Adjournment February 12,2Ol9 Date of Prorogation February 12, 2019 (At the conclusion of its sitting) Number of sittings l0 (Ten) Panrv poslrtoN oR FounreEnrH KennI-a Leclsuettve AsspNasuv (As ox JeNuenY 25,2019) Ruling Communist Party of India (Marxist) 58 Communist Party of India .. l9 Janata Dal (Secular) 03 Nationalist Congress Party 02 Congress (Secular) 0t Kerala Congress (B) 0l Communist Marxist Party Kerala State Committee 0l National Secular Conference 0l Independents 05 Opposition Indian National Congress 22 Indian Union Muslim lrage l7 Kerala Congress (M) 06 Ke.rala Congress (Jacob) 0l Bharatiya Janata Party 0l Independents 0l Total .. 139 Speaker o .. 0l Grand Total ..140 Speaker SHnr P. Sneeneuexntsxxer.t Deputy Speaker Sunl V. Snsr Council of Membert l. Shri Pinarayi Vijayan, Chief Minister 2. Shri A. K. Balan, Minister for welfare of Scheduled castes, scheduled Tribes, Backward Classes, Law, Culture and Parliamentary Affairs 3. Shri E. Chandrasekharan, Minister for Revenue & Housing 4. Dr. K. T. Jaleel, Minister for Higher Education, Welfare of Minorities' Wakf & Haji Pilgrimage 5. Shri E. P. Jayarajan, Minister for Industries, Sports & Youth Affain 6. Shri M. M. Mani, Minister for Electricity 7, Shd'K. Krishnankutty, Ministei for Wtter Resources' 8. -

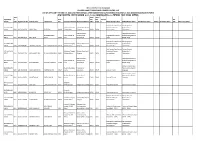

Eforms Publication of SEM-VI, 2021 on 7-9-2021.Xlsx

THE UNIVERSITY OF BURDWAN COLLEGE NAME- TARAKESWAR DEGREE COLLEGE- 415 LIST OF APPLICANT FOR SEM -VI, 2020 AND THEIR DETAILS AFTER SUBMITTING BA/BCOM/BSC (H/G) SEM-VI, 2021 ONLINE EXAMINATION FORM (যারা অনলাইন পেম কেরেছ ৯/০৭/২০২১ (বার) রাত ৮.০০ িমিনেটর মেধ তােদর তািলকা) Cours Hons/ Hons/ Application e Hons Gen Gen Gen Sub- SEC Seq No Code Registration No Student Name Father Name Sub Honours Sub CC-13 Honours Sub CC-14 Sub-1 Sub-2 3 DSE-3/1B Topic Name DSE-4/2BTopic Name DSE-3B Topic Name GE Sub GE-2 Topic Name Sub SEC-4 Topic Name Bish Sataker Swadhinata- Sahitya Bisayak 20216415AH0 Sanskrita O Ingreji Sahityer Rup- Riti O Purbabarti Bangla Prabandha O 29030 BAH 201501064828 SRIBAS BAG DILIP BAG BNGH Sahityer Itihas Sangrup BNGH BNGH Kathasahitya Lakasahitya Rabindranath's Stage Demonstration - 20216415AH0 DIPENDRA NATH Khyal Vilambit & Gitinatya and Stage Demonstration - Rabindra Sangeet and 33874 BAH 201501070379 ADITI BERA BERA MUCH Drut Nrityanatya MUCH MUCH Khyal Bengali Song Bish Sataker Swadhinata- Sahitya Bisayak 20216415AH0 Sanskrita O Ingreji Sahityer Rup- Riti O Purbabarti Bangla Prabandha O 28925 BAH 201601067467 CHANDRA SANTRA ASIT KUMAR SANTRA BNGH Sahityer Itihas Sangrup BNGH BNGH Kathasahitya Lakasahitya Bish Sataker Swadhinata- Sahitya Bisayak 20216415AH0 Sanskrita O Ingreji Sahityer Rup- Riti O Purbabarti Bangla Prabandha O 28717 BAH 201601073761 MADHUMITA BALI SHYAMSUNDAR BALI BNGH Sahityer Itihas Sangrup BNGH BNGH Kathasahitya Lakasahitya Rabindranath's Stage Demonstration - 20216415AH0 Khyal Vilambit & Gitinatya and -

Madhusudan Dutt and the Dilemma of the Early Bengali Theatre Dhrupadi

Layered homogeneities: Madhusudan Dutt and the dilemma of the early Bengali theatre Dhrupadi Chattopadhyay Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 5–34 | ISSN 2050-487X | www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk 2016 | The South Asianist 4 (2): 5-34 | pg. 5 Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 5-34 Layered homogeneities: Madhusudan Dutt, and the dilemma of the early Bengali theatre DHRUPADI CHATTOPADHYAY, SNDT University, Mumbai Owing to its colonial tag, Christianity shares an uneasy relationship with literary historiographies of nineteenth-century Bengal: Christianity continues to be treated as a foreign import capable of destabilising the societal matrix. The upper-caste Christian neophytes, often products of the new western education system, took to Christianity to register socio-political dissent. However, given his/her socio-political location, the Christian convert faced a crisis of entitlement: as a convert they faced immediate ostracising from Hindu conservative society, and even as devout western moderns could not partake in the colonizer’s version of selective Christian brotherhood. I argue that Christian convert literature imaginatively uses Hindu mythology as a master-narrative to partake in both these constituencies. This paper turns to the reception aesthetics of an oft forgotten play by Michael Madhusudan Dutt, the father of modern Bengali poetry, to explore the contentious relationship between Christianity and colonial modernity in nineteenth-century Bengal. In particular, Dutt’s deft use of the semantic excess as a result of the overlapping linguistic constituencies of English and Bengali is examined. Further, the paper argues that Dutt consciously situates his text at the crossroads of different receptive constituencies to create what I call ‘layered homogeneities’. -

![296] CHENNAI, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2010 Purattasi 15, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2041](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7728/296-chennai-friday-october-1-2010-purattasi-15-thiruvalluvar-aandu-2041-407728.webp)

296] CHENNAI, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2010 Purattasi 15, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2041

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2009-11. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2010 [Price: Rs. 20.00 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 296] CHENNAI, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2010 Purattasi 15, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2041 Part V—Section 4 Notifications by the Election Commission of India. NOTIFICATIONS BY THE ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA ELECTION SYMBOLS (RESERVATION AND ALLOTMENT) ORDER, 1968 No. SRO G-33/2010. The following Notification of the Election Commission of India, Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi-110 001, dated 17th September, 2010 [26 Bhadrapada, 1932 (Saka)] is republished:— Whereas, the Election Commission of India has decided to update its Notification No. 56/2009/P.S.II, dated 14th September, 2009, specifying the names of recognised National and State Parties, registered-unrecognised parties and the list of free symbols, issued in pursuance of paragraph 17 of the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968, Now, therefore, in pursuance of paragraph 17 of the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment) Order, 1968, and in supersession of its aforesaid Notification No. 56/2009/P.S.II, dated 14th September, 2009, as amended from time to time, published in the Gazette of India, Extraordinary, Part II—Section-3, sub-section (iii), the Election Commission of India hereby specifies :— (a) In Table I, the National Parties and the Symbols respectively reserved for them and postal address of their Headquarters ; (b) In Table II, the State Parties, the State or States in which they are State Parties and the Symbols respectively reserved for them in such State or States and postal address of their Headquarters; (c) In Table III, the registered-unrecognised political parties and postal address of their Headquarters; and (d) In Table IV, the free symbols. -

01720Joya Chatterji the Spoil

This page intentionally left blank The Spoils of Partition The partition of India in 1947 was a seminal event of the twentieth century. Much has been written about the Punjab and the creation of West Pakistan; by contrast, little is known about the partition of Bengal. This remarkable book by an acknowledged expert on the subject assesses partition’s huge social, economic and political consequences. Using previously unexplored sources, the book shows how and why the borders were redrawn, as well as how the creation of new nation states led to unprecedented upheavals, massive shifts in population and wholly unexpected transformations of the political landscape in both Bengal and India. The book also reveals how the spoils of partition, which the Congress in Bengal had expected from the new boundaries, were squan- dered over the twenty years which followed. This is an original and challenging work with findings that change our understanding of parti- tion and its consequences for the history of the sub-continent. JOYA CHATTERJI, until recently Reader in International History at the London School of Economics, is Lecturer in the History of Modern South Asia at Cambridge, Fellow of Trinity College, and Visiting Fellow at the LSE. She is the author of Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition (1994). Cambridge Studies in Indian History and Society 15 Editorial board C. A. BAYLY Vere Harmsworth Professor of Imperial and Naval History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow of St Catharine’s College RAJNARAYAN CHANDAVARKAR Late Director of the Centre of South Asian Studies, Reader in the History and Politics of South Asia, and Fellow of Trinity College GORDON JOHNSON President of Wolfson College, and Director, Centre of South Asian Studies, University of Cambridge Cambridge Studies in Indian History and Society publishes monographs on the history and anthropology of modern India. -

IJRESS Volume 6, Issue 2

International Journal of Research in Economics and Social Sciences (IJRESS) Available online at: http://euroasiapub.org Vol. 7 Issue 7, July- 2017 ISSN(o): 2249-7382 | Impact Factor: 6.939 | Thomson Reuters Researcher ID: L-5236-2015 Dissemination of social messages by Folk Media – A case study through folk drama Bolan of West Bengal Mr. Sudipta Paul Research Scholar, Department of Mass Communication & Videography, Rabindra Bharati University Abstract: In the vicinity of folk-culture, folk drama is of great significance because it reflects the society by maintaining a non-judgemental stance. It has a strong impact among the audience as the appeal of Bengali folk-drama is undeniable. ‘Bolan’ is a traditional folk drama of Bengal which is mainly celebrated in the month of ‘Chaitra’ (march-april). Geographically, it is prevalent in the mid- northern rural and semi-urban regions of Bengal (Rar Banga area) – mainly in Murshidabad district and some parts of Nadia, Birbhum and Bardwan districts. Although it follows the theatrical procedures, yet it is different from the same because it has no female artists. The male actors impersonate as females and play the part. Like other folk drama ‘Bolan’ is in direct contact with the audience and is often interacted and modified by them. Primarily it narrates mythological themes but now-a-days it narrates contemporary socio-politico-economical and natural issues. As it is performed different contemporary issues of immense interest audiences is deeply integrated with it and try to assimilate the messages of social importance from it. And in this way Mass (traditional) media plays an important role in shaping public opinion and forming a platform of exchange between the administration and the people they serve.