Ed 126 518 Author Pub Date Note Journal Cit Edrs Price

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Numbers in Bengali Language

NUMBERS IN BENGALI LANGUAGE A dissertation submitted to Assam University, Silchar in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts in Department of Linguistics. Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGE ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR 788011, INDIA YEAR OF SUBMISSION : 2020 CONTENTS Title Page no. Certificate 1 Declaration by the candidate 2 Acknowledgement 3 Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1.0 A rapid sketch on Assam 4 1.2.0 Etymology of “Assam” 4 Geographical Location 4-5 State symbols 5 Bengali language and scripts 5-6 Religion 6-9 Culture 9 Festival 9 Food havits 10 Dresses and Ornaments 10-12 Music and Instruments 12-14 Chapter 2: REVIEW OF LITERATURE 15-16 Chapter 3: OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY Objectives 16 Methodology and Sources of Data 16 Chapter 4: NUMBERS 18-20 Chapter 5: CONCLUSION 21 BIBLIOGRAPHY 22 CERTIFICATE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR DATE: 15-05-2020 Certified that the dissertation/project entitled “Numbers in Bengali Language” submitted by Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 of 2018-2019 for Master degree in Linguistics in Assam University, Silchar. It is further certified that the candidate has complied with all the formalities as per the requirements of Assam University . I recommend that the dissertation may be placed before examiners for consideration of award of the degree of this university. 5.10.2020 (Asst. Professor Paramita Purkait) Name & Signature of the Supervisor Department of Linguistics Assam University, Silchar 1 DECLARATION I hereby Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No – 03-120032252 hereby declare that the subject matter of the dissertation entitled ‘Numbers in Bengali language’ is the record of the work done by me. -

DEPARTMENT of FOLKLORE University of Kalyani

DEPARTMENT OF FOLKLORE University of Kalyani COURSE CURRICULA OF M.A. IN FOLKLORE (Two- years Master’s Degree Programme under the Scheme of CBCS) Session: 2017-2018 and onwards As recommended by the Post Graduate Board of Studies (PGBoS) in Folklore in the meeting held on May 05, 2017 OPERATIONAL ASPECTS A. Timetable: 1) Class-hour will be of 1 hour and the time schedule of classes should be from 10.30 a.m. to 5.00 p.m. with 30 minutes lunch-break during 1.30 to 2.00 p.m., from Monday to Friday. Thus there shall be maximum 6 classes a day. 2) Normal 16 class-hours in a week may be kept for direct class instructions. The remaining 14 hours in a week shall be kept for Tutorial, Dissertation, Seminar, Assignments, Special Classes, holding class-tests etc. as may be required for the course. B. Course-papers and Allocation of Class-Hours per Course: 1) For evaluation purposes, each course shall be of 100 marks and for each course of 100 marks total number of direct instruction hours (theory/practical/field-training) shall be 48 hours. 2) The full course in 4 semesters shall be of total 1600 marks with total 16 courses (Fifteen Core Courses & One Open Course). In each semester, the course work shall be for 4 courses of total 400 marks. C. Credit Specification of the Course Curricula: M.A. Course in Folklore shall comprise 4 semesters. Each semester shall have 4 courses. In all, there shall be 16 courses of 4 credits each. -

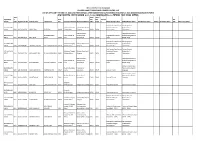

Eforms Publication of SEM-VI, 2021 on 7-9-2021.Xlsx

THE UNIVERSITY OF BURDWAN COLLEGE NAME- TARAKESWAR DEGREE COLLEGE- 415 LIST OF APPLICANT FOR SEM -VI, 2020 AND THEIR DETAILS AFTER SUBMITTING BA/BCOM/BSC (H/G) SEM-VI, 2021 ONLINE EXAMINATION FORM (যারা অনলাইন পেম কেরেছ ৯/০৭/২০২১ (বার) রাত ৮.০০ িমিনেটর মেধ তােদর তািলকা) Cours Hons/ Hons/ Application e Hons Gen Gen Gen Sub- SEC Seq No Code Registration No Student Name Father Name Sub Honours Sub CC-13 Honours Sub CC-14 Sub-1 Sub-2 3 DSE-3/1B Topic Name DSE-4/2BTopic Name DSE-3B Topic Name GE Sub GE-2 Topic Name Sub SEC-4 Topic Name Bish Sataker Swadhinata- Sahitya Bisayak 20216415AH0 Sanskrita O Ingreji Sahityer Rup- Riti O Purbabarti Bangla Prabandha O 29030 BAH 201501064828 SRIBAS BAG DILIP BAG BNGH Sahityer Itihas Sangrup BNGH BNGH Kathasahitya Lakasahitya Rabindranath's Stage Demonstration - 20216415AH0 DIPENDRA NATH Khyal Vilambit & Gitinatya and Stage Demonstration - Rabindra Sangeet and 33874 BAH 201501070379 ADITI BERA BERA MUCH Drut Nrityanatya MUCH MUCH Khyal Bengali Song Bish Sataker Swadhinata- Sahitya Bisayak 20216415AH0 Sanskrita O Ingreji Sahityer Rup- Riti O Purbabarti Bangla Prabandha O 28925 BAH 201601067467 CHANDRA SANTRA ASIT KUMAR SANTRA BNGH Sahityer Itihas Sangrup BNGH BNGH Kathasahitya Lakasahitya Bish Sataker Swadhinata- Sahitya Bisayak 20216415AH0 Sanskrita O Ingreji Sahityer Rup- Riti O Purbabarti Bangla Prabandha O 28717 BAH 201601073761 MADHUMITA BALI SHYAMSUNDAR BALI BNGH Sahityer Itihas Sangrup BNGH BNGH Kathasahitya Lakasahitya Rabindranath's Stage Demonstration - 20216415AH0 Khyal Vilambit & Gitinatya and -

Music As a Means of Communication 1

International Journal of English Learning and Teaching Skills; Vol. 3, No. 1; Oct 2020,ISSN: 2639-7412 (Print) ISSN: 2638-5546 (Online) Running Head: MUSIC AS A MEANS OF COMMUNICATION 1 Music As A Means Of Communication Saswata Saha Soujanya Syamal Anavivab Kar Institute of Engineering and Management 1688 International Journal of English Learning and Teaching Skills; Vol. 3, No. 1; Oct 2020,ISSN: 2639-7412 (Print) ISSN: 2638-5546 (Online) Running Head: MUSIC AS A MEANS OF COMMUNICATION 2 Abstract It is no doubt that communication plays a vital role in human life most importantly in our day to day lives .It not only helps to facilitate the process of sharing information and knowledge but also helps to develop relationship among different people over the world. We should learn to communicate effectively to make the world a better place live in Communication is a skill which involves systematic and continuous process of speaking, listening ,understanding and hearing. Most people are born with the ability of speaking and listening .Listening is one of the vital ability to understand verbal and non verbal cues are the skills by observing other people and modelling our behaviour on what we see and perceived is acknowledged passport to better education and employement oppurtunities .Music plays a crucial role to our emotions or to our beloved someones. Most of the people in the world love to listen music .There is a message in the lyrics of the song which the composer wants to gives us. Keywords:- Communication, music 1689 International Journal of English Learning and Teaching Skills; Vol. -

IJRESS Volume 6, Issue 2

International Journal of Research in Economics and Social Sciences (IJRESS) Available online at: http://euroasiapub.org Vol. 7 Issue 7, July- 2017 ISSN(o): 2249-7382 | Impact Factor: 6.939 | Thomson Reuters Researcher ID: L-5236-2015 Dissemination of social messages by Folk Media – A case study through folk drama Bolan of West Bengal Mr. Sudipta Paul Research Scholar, Department of Mass Communication & Videography, Rabindra Bharati University Abstract: In the vicinity of folk-culture, folk drama is of great significance because it reflects the society by maintaining a non-judgemental stance. It has a strong impact among the audience as the appeal of Bengali folk-drama is undeniable. ‘Bolan’ is a traditional folk drama of Bengal which is mainly celebrated in the month of ‘Chaitra’ (march-april). Geographically, it is prevalent in the mid- northern rural and semi-urban regions of Bengal (Rar Banga area) – mainly in Murshidabad district and some parts of Nadia, Birbhum and Bardwan districts. Although it follows the theatrical procedures, yet it is different from the same because it has no female artists. The male actors impersonate as females and play the part. Like other folk drama ‘Bolan’ is in direct contact with the audience and is often interacted and modified by them. Primarily it narrates mythological themes but now-a-days it narrates contemporary socio-politico-economical and natural issues. As it is performed different contemporary issues of immense interest audiences is deeply integrated with it and try to assimilate the messages of social importance from it. And in this way Mass (traditional) media plays an important role in shaping public opinion and forming a platform of exchange between the administration and the people they serve. -

Department of Music Rabindra Sangeet Hons

Department of Music Rabindra Sangeet Hons. Section Nistarini College, Purulia (Govt. Sponsored and affliated to Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University) Course Outcome The I St paper (101) is Practical. This paper consists of Rabindra Sangeet of 6 Paryas Semester I (I) and some chota kheyals at preliminary level. Students learn the holistic concept of B.A. Hons in Music Rabindra Sangeet in the preliminary level. (Rabindra Sangeet) The 2nd Paper (102) is theoretical. Outline History of Music in Bengal and knowledge of`Raga and Tala GE1 Students of other Hons stream of Sem I and Programme course of Sem V develops foundation of basic knowledge of Rabindi.a Sangeet and chhota kheyal -Practical Paper. Semester 11 The paper 201 is Practical. This paper consists of selected songs based on various B.A. Hons in Music Paryas (]1). (Rabindra Sangeet) The paper 202 is theoretical - general i\'nowledge relating to influence of various songs on Rabindranath's creation. GE2 Students of other Hons stream of Sem 11 and Programme course of Sem Vl develops basic knowledge of selected songs based on various Paryas and knowledge of that ragas. Practical Paper. Two practical papers 301 - selected songs based on various tala coveriiig various Semester 111 Paryas' and types -I. B.A. Hons in Music 302 (Practical) - Selected songs based on various tala covering various Paryas' and types - 11. Paper 303 (Theory) -Knowledge of Ragas, talas and influence of folk (Rabindra Sangeet) songs on Rabindra Sangeet. SEC-1 paper (Theory) -General Aesthetics falls into this category. Semester IV Paper 401 (Practical) -Songs of Rabindranath covering various songs of six Paryas B.A. -

Wedding Videos

P1: IML/IKJ P2: IML/IKJ QC: IML/TKJ T1: IML PB199A-20 Claus/6343F August 21, 2002 16:35 Char Count= 0 WEDDING VIDEOS band, the blaring recorded music of a loudspeaker, the References cries and shrieks of children, and the conversations of Archer, William. 1985. Songs for the bride: wedding rites of adults. rural India. New York: Columbia University Press. Most wedding songs are textually and musically Henry, Edward O. 1988. Chant the names of God: musical cul- repetitive. Lines of text are usually repeated twice, en- ture in Bhojpuri-Speaking India. San Diego: San Diego State abling other women who may not know the song to University Press. join in. The text may also be repeated again and again, Narayan, Kirin. 1986. Birds on a branch: girlfriends and wedding songs in Kangra. Ethos 14: 47–75. each time inserting a different keyword into the same Raheja, Gloria, and Ann Gold. 1994. Listen to the heron’s words: slot. For example, in a slot for relatives, a wedding song reimagining gender and kinship in North India. Berkeley: may be repeated to include father and mother, father’s University of California Press. elder brother and his wife, the father’s younger brother and his wife, the mother’s brother and his wife, paternal KIRIN NARAYAN grandfather and grandmother, brother and sister-in-law, sister and brother-in-law, and so on. Alternately, in a slot for objects, one may hear about the groom’s tinsel WEDDING VIDEOS crown, his shoes, watch, handkerchief, socks, and so on. Wedding videos are fast becoming the most com- Thus, songs can be expanded or contracted, adapting to mon locally produced representation of social life in the performers’ interest or the length of a particular South Asia. -

"I Miss My Country, but My World Is with My Children": Examining the Family and Social Lives of Older Indian Immigrants in the United States

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Gerontology Theses Gerontology Institute Summer 8-18-2010 "I Miss My Country, but My World is with My Children": Examining the Family and Social Lives of Older Indian Immigrants in the United States Karuna Sharma Gerontology Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/gerontology_theses Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Sharma, Karuna, ""I Miss My Country, but My World is with My Children": Examining the Family and Social Lives of Older Indian Immigrants in the United States." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2010. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/gerontology_theses/21 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Gerontology Institute at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gerontology Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “I MISS MY COUNTRY, BUT MY WORLD IS WITH MY CHILDREN”: EXAMINING THE FAMILY AND SOCIAL LIVES OF OLDER INDIAN IMMIGRANTS IN THE UNITED STATES by KARUNA SHARMA ABSTRACT Within the context of ongoing social and demographic transformation, including t h e t r e n d t o w a r d s globalization, changing patterns of longevity and increasing ethnic diversity, this thesis examines the lives older Asian-Indian immigrants in the United States. To date, much of what little research exists on this group of elders focuses on acculturation and related stress, but there is limited research on the daily life experiences of these older adults, particularly as they pertain to family life, the practice of filial piety, and informal support exchange within their households, as well as their social lives more generally. -

Origins of Marriage Customs

ORIGINS OF MARRIAGE CUSTOMS: AN ANALYSIS OF RELIGIOUS TRADITIONS HONORS THESIS Presented to the Honors Committee of Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation in the Honors College by Kourtney Lynn Ruth San Marcos, Texas May 2018 ORIGINS OF MARRIAGE CUSTOMS: AN ANALYSIS OF RELIGIOUS TRADITIONS Thesis Supervisor: ________________________________ Stefanie Ramirez, Ph.D. School of Family and Consumer Sciences Approved: ____________________________________ Heather C. Galloway, Ph.D. Dean, Honors College COPYRIGHT by Kourtney Ruth 2018 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Kourtney Ruth, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My thesis would not have been possible without the guidance and support of my thesis supervisor, Dr. Stefanie Ramirez. She has been diligent in providing me with feedback and suggestions since the beginning of this process. She did not have to take on the extra responsibility of supervising me during this extremely busy semester, I am so thankful for everything she has done for me! My parents have always pushed me to do my absolute best at eveything I do. They molded me into the competitive person I am today, and without their motivation and support, I would never have been in the honors college in the first place. -

Arts-Integrated Learning

ARTS-INTEGRATED LEARNING THE FUTURE OF CREATIVE AND JOYFUL PEDAGOGY The NCF 2005 states, ”Aesthetic sensibility and experience being the prime sites of the growing child’s creativity, we must bring the arts squarely into the domain of the curricular, infusing them in all areas of learning while giving them an identity of their own at relevant stages. If we are to retain our unique cultural identity in all its diversity and richness, we need to integrate art education in the formal schooling of our students for helping them to apply art-based enquiry, investigation and exploration, critical thinking and creativity for a deeper understanding of the concepts/topics. This integration broadens the mind of the student and enables her / him to see the multi- disciplinary links between subjects/topics/real life. Art Education will continue to be an integral part of the curriculum, as a co-scholastic area and shall be mandatory for Classes I to X. Please find attached the rich cultural heritage of India and its cultural diversity in a tabular form for reading purpose. The young generation need to be aware of this aspect of our country which will enable them to participate in Heritage Quiz under the aegis of CBSE. TRADITIONAL TRADITIONAL DANCES FAIRS & FESTIVALS ART FORMS STATES & UTS DRESS FOOD (ILLUSTRATIVE) (ILLUSTRATIVE) (ILLUSTRATIVE) (ILLUSTRATIVE) (ILLUSTRATIVE) Kuchipudi, Burrakatha, Tirupati Veerannatyam, Brahmotsavam, Dhoti and kurta Kalamkari painting, Pootha Remus Andhra Butlabommalu, Lumbini Maha Saree, Langa Nirmal Paintings, Gongura Pradesh Dappu, Tappet Gullu, Shivratri, Makar Voni, petticoat, Cherial Pachadi Lambadi, Banalu, Sankranti, Pongal, Lambadies Dhimsa, Kolattam Ugadi Skullcap, which is decorated with Weaving, carpet War dances of laces and fringes. -

'Aradhona' a University of Visual & Performing Arts By

‘ARADHONA’ A UNIVERSITY OF VISUAL & PERFORMING ARTS BY IFREET RAHIMA 09108004 SEMINAR II Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelors of Architecture Department of Architecture BRAC University SUMMER 2013 DISSERTATION THE DESIGN OF ‘ARADHONA’ A UNIVERSITY OF VISUAL & PERFORMING ARTS This dissertation is submitted to the Department of Architecture in partial gratification of the exigency for the degree of Bachelor of Architecture (B.Arch.) at BRAC University, Dhaka, Bangladesh IFREET RAHIMA 09108004 5TH YEAR, DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE BRAC UNIVERSITY, DHAKA FALL 2013 DECLARATION The work contained in this study has not been submitted elsewhere for any other degree or qualification and unless otherwise referenced it is the author’s own work. STATEMENT OF COPYRIGHT The copyright of this dissertation rests with the Architecture Discipline. No quotation from it should be published without their consent. RAHIMA | i ‘ARADHONA’ A UNIVERSITY OF VISUAL & PERFORMING ARTS A Design Dissertation submitted to the Department of Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree of Bachelor of Architecture (B.Arch) under the Faculty of BRAC University, Dhaka. The textual and visual contents of the Design Dissertation are the intellectual output of the student mentioned below unless otherwise mentioned. Information given within this Design Dissertation is true to the best knowledge of the student mentioned below. All possible efforts have been made by the author to acknowledge the secondary sources information. Right to further modification and /or publication of this Design Dissertation in any form belongs to its author. Contents within this Design Dissertation can be reproduced with due acknowledgement for academic purposes only without written consent from the author. -

A Journey of a Woman in Search of True Love and She Drifted to Understand the Concept of Transcendental Oneness

Laali A journey of a woman in search of true love and she drifted to understand the concept of transcendental oneness. 1 About the Author The author has education in epistemology and taught philosophy and culture in the university. He is working as a senior journalist and covered socio- economic stories in Rajasthan and Gujarat- great states of culture and customs of India. 2 The story of an illiterate woman of Rajasthan in India who in her journey of finding transcendental love realizes that marriage is not only the answer. After her broken marriage she tries several live in-relationships to find true love. She knows that the feeling of transcendental love, a love beyond logic and reasoning, exists and she starts searching the meaning of love, during her journey, she tries to understand principles of Hindu religion and philosophy to understand the reality and truth that fabricates the society to live in accordance with right knowledge. The lower communities that remained suppressed for thousands of years have their own customs and rituals and have their own closed society but unfortunately their literatures and customs got no place in writing because education was mostly limited to upper class. The story also tells that Indian philosophy was never applied to get the real advantage of such knowledge. And therefore philosophies remained just reciting of books and prevailing system of society and confused common man. I am thankful to my daughter Sanghamitra and son Kumar Bodhisattva who persuaded me to continue my writing. They came in my life as little angels. 3 Index 1.