16 · Cartography in the Ancient World: a Conclusion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nicolas-Auguste Tissot: a Link Between Cartography and Quasiconformal Theory

NICOLAS-AUGUSTE TISSOT: A LINK BETWEEN CARTOGRAPHY AND QUASICONFORMAL THEORY ATHANASE PAPADOPOULOS Abstract. Nicolas-Auguste Tissot (1824{1897) published a series of papers on cartography in which he introduced a tool which became known later on, among geographers, under the name of the Tissot indicatrix. This tool was broadly used during the twentieth century in the theory and in the practical aspects of the drawing of geographical maps. The Tissot indicatrix is a graph- ical representation of a field of ellipses on a map that describes its distortion. Tissot studied extensively, from a mathematical viewpoint, the distortion of mappings from the sphere onto the Euclidean plane that are used in drawing geographical maps, and more generally he developed a theory for the distor- sion of mappings between general surfaces. His ideas are at the heart of the work on quasiconformal mappings that was developed several decades after him by Gr¨otzsch, Lavrentieff, Ahlfors and Teichm¨uller.Gr¨otzsch mentions the work of Tissot and he uses the terminology related to his name (in particular, Gr¨otzsch uses the Tissot indicatrix). Teichm¨ullermentions the name of Tissot in a historical section in one of his fundamental papers where he claims that quasiconformal mappings were used by geographers, but without giving any hint about the nature of Tissot's work. The name of Tissot is also missing from all the historical surveys on quasiconformal mappings. In the present paper, we report on this work of Tissot. We shall also mention some related works on cartography, on the differential geometry of surfaces, and on the theory of quasiconformal mappings. -

The Dunhuang Chinese Sky: a Comprehensive Study of the Oldest Known Star Atlas

25/02/09JAHH/v4 1 THE DUNHUANG CHINESE SKY: A COMPREHENSIVE STUDY OF THE OLDEST KNOWN STAR ATLAS JEAN-MARC BONNET-BIDAUD Commissariat à l’Energie Atomique ,Centre de Saclay, F-91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France E-mail: [email protected] FRANÇOISE PRADERIE Observatoire de Paris, 61 Avenue de l’Observatoire, F- 75014 Paris, France E-mail: [email protected] and SUSAN WHITFIELD The British Library, 96 Euston Road, London NW1 2DB, UK E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This paper presents an analysis of the star atlas included in the medieval Chinese manuscript (Or.8210/S.3326), discovered in 1907 by the archaeologist Aurel Stein at the Silk Road town of Dunhuang and now held in the British Library. Although partially studied by a few Chinese scholars, it has never been fully displayed and discussed in the Western world. This set of sky maps (12 hour angle maps in quasi-cylindrical projection and a circumpolar map in azimuthal projection), displaying the full sky visible from the Northern hemisphere, is up to now the oldest complete preserved star atlas from any civilisation. It is also the first known pictorial representation of the quasi-totality of the Chinese constellations. This paper describes the history of the physical object – a roll of thin paper drawn with ink. We analyse the stellar content of each map (1339 stars, 257 asterisms) and the texts associated with the maps. We establish the precision with which the maps are drawn (1.5 to 4° for the brightest stars) and examine the type of projections used. -

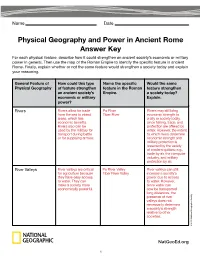

Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer

Name Date Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key For each physical feature, describe how it could strengthen an ancient society’s economic or military power in general. Then use the map of the Roman Empire to identify the specific feature in ancient Rome. Finally, explain whether or not the same feature would strengthen a society today and explain your reasoning. General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. a society today? economic or military Explain. power? Rivers Rivers allow for trade Po River Rivers may still bring from the sea to inland Tiber River economic strength to areas, which has a city or society today, economic benefits. since fishing, trade, and Rivers also can be protection are offered by used by the military for water. However, the extent transport during battle to which rivers determine or for supplying armies. economic strength and military protection is lessened by the variety of modern options: e.g., trade by air, the computer industry, and military protection by air. River Valleys River valleys are critical Po River Valley River valleys can still for agriculture because Tiber River Valley increase a society’s they have easy access power due to access to water. They can to water. However, make a society more since water can economically powerful. now be transported long distances, the presence of river valleys does not necessarily determine a society’s strength relative to other societies. © 2015 National Geographic Society NatGeoEd.org 1 Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key, continued General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. -

Mercator-15Dec2015.Pdf

THE MERCATOR PROJECTIONS THE NORMAL AND TRANSVERSE MERCATOR PROJECTIONS ON THE SPHERE AND THE ELLIPSOID WITH FULL DERIVATIONS OF ALL FORMULAE PETER OSBORNE EDINBURGH 2013 This article describes the mathematics of the normal and transverse Mercator projections on the sphere and the ellipsoid with full deriva- tions of all formulae. The Transverse Mercator projection is the basis of many maps cov- ering individual countries, such as Australia and Great Britain, as well as the set of UTM projections covering the whole world (other than the polar regions). Such maps are invariably covered by a set of grid lines. It is important to appreciate the following two facts about the Transverse Mercator projection and the grids covering it: 1. Only one grid line runs true north–south. Thus in Britain only the grid line coincident with the central meridian at 2◦W is true: all other meridians deviate from grid lines. The UTM series is a set of 60 distinct Transverse Mercator projections each covering a width of 6◦in latitude: the grid lines run true north–south only on the central meridians at 3◦E, 9◦E, 15◦E, ... 2. The scale on the maps derived from Transverse Mercator pro- jections is not uniform: it is a function of position. For ex- ample the Landranger maps of the Ordnance Survey of Great Britain have a nominal scale of 1:50000: this value is only ex- act on two slightly curved lines almost parallel to the central meridian at 2◦W and distant approximately 180km east and west of it. The scale on the central meridian is constant but it is slightly less than the nominal value. -

Read Book the Atlas

THE ATLAS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK William T. Vollmann | 496 pages | 01 Jun 1997 | Penguin Books Australia | 9780140254495 | English | Hawthorn, Australia The Atlas PDF Book For a collection of maps, see atlas. For Atlas had worked out the science of astrology to a degree surpassing others and had ingeniously discovered the spherical nature of the stars, and for that reason was generally believed to be bearing the entire firmament upon his shoulders. On the Customize screen turn off the Use default mobile theme option under Advanced Options. Although Paloma was very young, she was a very happy and dedicated mother. Ancient Greek deities by affiliation. In addition to presenting geographic features and political boundaries, many atlases often feature geopolitical , social, religious and economic statistics. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Selected Weekly Fruit Movement and Price describes the change in shipment volume, farm prices, and retail prices of select fruit for the week noted. The people behind the movement. Namespaces Article Talk. Police never caught them, although the street was surveyed by video cameras. It provides fascinating insights into the world of politics, art, education, foreign policy, science, and more, rewarding you with a rich understanding of how ideas shape your world. October 20, AM Fruit and Tree Nuts Data Fruit and Tree Nuts Data provide users with comprehensive statistics on fresh and processed fruits, melons, and tree nuts in the United States, as well as some global data for these sectors. One is for sure the food. Examine the aspirations, arguments, strategies, and disasters of socialist theory and practice. -

Physical Geography of Southeast Asia

Physical Geography of SE Asia ©2012, TESCCC World Geography Unit 12, Lesson 01 Archipelago • A group of islands. Cordilleras • Parallel mountain ranges and plateaus, that extend into the Indochina Peninsula. Living on the Mainland • Mainland countries include Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos • Laos is a landlocked country • The landscape is characterized by mountains, rivers, river deltas, and plains • The climate includes tropical and mild • The monsoon creates a dry and rainy season ©2012, TESCCC Identify the mainland countries on your map. LAOS VIETNAM MYANMAR THAILAND CAMBODIA Human Settlement on the Mainland • People rely on the rivers that begin in the mountains as a source of water for drinking, transportation, and irrigation • Many people live in small villages • The river deltas create dense population centers • River create rich deposits of sediment that settle along central plains ©2012, TESCCC Major Cities on the Mainland • Myanmar- Yangon (Rangoon), Mandalay • Thailand- Bangkok • Vietnam- Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) • Cambodia- Phnom Penh ©2012, TESCCC Label the major cities on your map BANGKOK YANGON HO CHI MINH CITY PHNOM PEHN Chao Phraya River • Flows into the Gulf of Thailand, Bangkok is located along the river’s delta Irrawaddy River • Located in Myanmar, Rangoon located along the river Mekong River • Longest river in the region, forms part of the borders of Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand, empties into the South China Sea in Vietnam Label the important rivers and the bodies of water on your map. MEKONG IRRAWADDY CHAO PRAYA ©2012, TESCCC Living on the Islands • The island nations are fragmented • Nations are on islands are made up of island groups. -

Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia

CHRISTINA SKELTON Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia The Ancient Greek dialect of Pamphylia shows extensive influence from the nearby Anatolian languages. Evidence from the linguistics of Greek and Anatolian, sociolinguistics, and the histor- ical and archaeological record suggest that this influence is due to Anatolian speakers learning Greek as a second language as adults in such large numbers that aspects of their L2 Greek became fixed as a part of the main Pamphylian dialect. For this linguistic development to occur and persist, Pamphylia must initially have been settled by a small number of Greeks, and remained isolated from the broader Greek-speaking community while prevailing cultural atti- tudes favored a combined Greek-Anatolian culture. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND The Greek-speaking world of the Archaic and Classical periods (ca. ninth through third centuries BC) was covered by a patchwork of different dialects of Ancient Greek, some of them quite different from the Attic and Ionic familiar to Classicists. Even among these varied dialects, the dialect of Pamphylia, located on the southern coast of Asia Minor, stands out as something unusual. For example, consider the following section from the famous Pamphylian inscription from Sillyon: συ Διϝι̣ α̣ ̣ και hιιαροισι Μανεˉ[ς .]υαν̣ hελε ΣελυW[ι]ιυ̣ ς̣ ̣ [..? hι†ια[ρ]α ϝιλ̣ σιι̣ ọς ̣ υπαρ και ανιιας̣ οσα περ(̣ ι)ι[στα]τυ ̣ Wοικ[. .] The author would like to thank Sally Thomason, Craig Melchert, Leonard Neidorf and the anonymous reviewer for their valuable input, as well as Greg Nagy and everyone at the Center for Hellenic Studies for allowing me to use their library and for their wonderful hospitality during the early stages of pre- paring this manuscript. -

THE LYCIAN PEOPLE and THEIR ENVIRONMENT 1 Geography And

CHAP'IERTWO THE LYCIAN PEOPLE AND THEIR ENVIRONMENT 1 Geography and communications in Lycia1 Lycia lies on the south-west coast of Asia Minor, between Caria and Pam phylia. At the period of its smallest extent, at the time of the Persian con quest, the Lycian state covered an area comparable in size to Attica, ex tending over most of the territory of the Xanthos valley, probably as far north as Araxa, more than forty kilometres away from Xanthos, and nearly fifty from the Mediterranean; Bryce has argued that to Homer 'Lycia' meant no more than the Xanthos valley. 2 At its largest, under Perikle of Limyra (pp. 154-70), the Lycian state was comparable in size to the south ern Peloponnese (i.e. Laconia and Messenia), stretching from Phaselis in the east to Telemessos in the north-west, nearly a hundred and thirty kilo metres as the crow flies, and included a large section of southern Milyas, if not all of it (p. 20). It is separated from its neighbours by high mountains which hampered movement in antiquity. 3 This remoteness continued into modern times-when Bean first visited the area in 1946 he found a country where tractors were unknown, and: When I asked, 'What do you do in the winter?', the answer was, 'We sit'.4 Three great chains determine access to and within Lycia. In the west two spurs of the western Tauros, the Boncuk Daglan and the Baba Dag1 (this latter being ancient Mt. Kragos and Mt. Antikragos) restrict access to Ly cia to the pass between them, east of Telemessos. -

A New Geography of European Power?

A NEW GEOGRAPHY OF EUROPEAN POWER? EGMONT PAPER 42 A NEW GEOGRAPHY OF EUROPEAN POWER? James ROGERS January 2011 The Egmont Papers are published by Academia Press for Egmont – The Royal Institute for International Relations. Founded in 1947 by eminent Belgian political leaders, Egmont is an independent think-tank based in Brussels. Its interdisciplinary research is conducted in a spirit of total academic freedom. A platform of quality information, a forum for debate and analysis, a melting pot of ideas in the field of international politics, Egmont’s ambition – through its publications, seminars and recommendations – is to make a useful contribution to the decision- making process. *** President: Viscount Etienne DAVIGNON Director-General: Marc TRENTESEAU Series Editor: Prof. Dr. Sven BISCOP *** Egmont - The Royal Institute for International Relations Address Naamsestraat / Rue de Namur 69, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Phone 00-32-(0)2.223.41.14 Fax 00-32-(0)2.223.41.16 E-mail [email protected] Website: www.egmontinstitute.be © Academia Press Eekhout 2 9000 Gent Tel. 09/233 80 88 Fax 09/233 14 09 [email protected] www.academiapress.be J. Story-Scientia NV Wetenschappelijke Boekhandel Sint-Kwintensberg 87 B-9000 Gent Tel. 09/225 57 57 Fax 09/233 14 09 [email protected] www.story.be All authors write in a personal capacity. Lay-out: proxess.be ISBN 978 90 382 1714 7 D/2011/4804/19 U 1547 NUR1 754 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publishers. -

General Index

General Index Italic page numbers refer to illustrations. Authors are listed in ical Index. Manuscripts, maps, and charts are usually listed by this index only when their ideas or works are discussed; full title and author; occasionally they are listed under the city and listings of works as cited in this volume are in the Bibliograph- institution in which they are held. CAbbas I, Shah, 47, 63, 65, 67, 409 on South Asian world maps, 393 and Kacba, 191 "Jahangir Embracing Shah (Abbas" Abywn (Abiyun) al-Batriq (Apion the in Kitab-i balJriye, 232-33, 278-79 (painting), 408, 410, 515 Patriarch), 26 in Kitab ~urat ai-arc!, 169 cAbd ai-Karim al-Mi~ri, 54, 65 Accuracy in Nuzhat al-mushtaq, 169 cAbd al-Rabman Efendi, 68 of Arabic measurements of length of on Piri Re)is's world map, 270, 271 cAbd al-Rabman ibn Burhan al-Maw~ili, 54 degree, 181 in Ptolemy's Geography, 169 cAbdolazlz ibn CAbdolgani el-Erzincani, 225 of Bharat Kala Bhavan globe, 397 al-Qazwlni's world maps, 144 Abdur Rahim, map by, 411, 412, 413 of al-BlrunI's calculation of Ghazna's on South Asian world maps, 393, 394, 400 Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra, 60 longitude, 188 in view of world landmass as bird, 90-91 Abu, Mount, Rajasthan of al-BlrunI's celestial mapping, 37 in Walters Deniz atlast, pl.23 on Jain triptych, 460 of globes in paintings, 409 n.36 Agapius (Mabbub) religious map of, 482-83 of al-Idrisi's sectional maps, 163 Kitab al- ~nwan, 17 Abo al-cAbbas Abmad ibn Abi cAbdallah of Islamic celestial globes, 46-47 Agnese, Battista, 279, 280, 282, 282-83 Mu\:lammad of Kitab-i ba/Jriye, 231, 233 Agnicayana, 308-9, 309 Kitab al-durar wa-al-yawaqft fi 11m of map of north-central India, 421, 422 Agra, 378 n.145, 403, 436, 448, 476-77 al-ra~d wa-al-mawaqft (Book of of maps in Gentil's atlas of Mughal Agrawala, V. -

The Magic of the Atwood Sphere

The magic of the Atwood Sphere Exactly a century ago, on June Dr. Jean-Michel Faidit 5, 1913, a “celestial sphere demon- Astronomical Society of France stration” by Professor Wallace W. Montpellier, France Atwood thrilled the populace of [email protected] Chicago. This machine, built to ac- commodate a dozen spectators, took up a concept popular in the eigh- teenth century: that of turning stel- lariums. The impact was consider- able. It sparked the genesis of modern planetariums, leading 10 years lat- er to an invention by Bauersfeld, engineer of the Zeiss Company, the Deutsche Museum in Munich. Since ancient times, mankind has sought to represent the sky and the stars. Two trends emerged. First, stars and constellations were easy, especially drawn on maps or globes. This was the case, for example, in Egypt with the Zodiac of Dendera or in the Greco-Ro- man world with the statue of Atlas support- ing the sky, like that of the Farnese Atlas at the National Archaeological Museum of Na- ples. But things were more complicated when it came to include the sun, moon, planets, and their apparent motions. Ingenious mecha- nisms were developed early as the Antiky- thera mechanism, found at the bottom of the Aegean Sea in 1900 and currently an exhibi- tion until July at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers in Paris. During two millennia, the human mind and ingenuity worked constantly develop- ing and combining these two approaches us- ing a variety of media: astrolabes, quadrants, armillary spheres, astronomical clocks, co- pernican orreries and celestial globes, cul- minating with the famous Coronelli globes offered to Louis XIV. -

The History of Cartography, Volume Six: Cartography in the Twentieth Century

The AAG Review of Books ISSN: (Print) 2325-548X (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rrob20 The History of Cartography, Volume Six: Cartography in the Twentieth Century Jörn Seemann To cite this article: Jörn Seemann (2016) The History of Cartography, Volume Six: Cartography in the Twentieth Century, The AAG Review of Books, 4:3, 159-161, DOI: 10.1080/2325548X.2016.1187504 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/2325548X.2016.1187504 Published online: 07 Jul 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 312 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rrob20 The AAG Review OF BOOKS The History of Cartography, Volume Six: Cartography in the Twentieth Century Mark Monmonier, ed. Chicago, document how all cultures of all his- IL: University of Chicago Press, torical periods represented the world 2015. 1,960 pp., set of 2 using maps” (Woodward 2001, 28). volumes, 805 color plates, What started as a chat on a relaxed 119 halftones, 242 line drawings, walk by these two authors in Devon, England, in May 1977 developed into 61 tables. $500.00 cloth (ISBN a monumental historia cartographica, 978-0-226-53469-5). a cartographic counterpart of Hum- boldt’s Kosmos. The project has not Reviewed by Jörn Seemann, been finished yet, as the volumes on Department of Geography, Ball the eighteenth and nineteenth cen- State University, Muncie, IN. tury are still in preparation, and will probably need a few more years to be published.