Gift Exchange in Seventeenth-Century Holland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tulip Symbolism in the Seventeenth-Century Dutch Emblem Book

Tulip symbolism in the seventeenth-century Dutch emblem book 0 Tulip symbolism in the seventeenth-century Dutch emblem book Research Master’s Thesis Utrecht University Faculty of the Humanities Art History of the Low Countries Emily Campbell 6114563 Supervisor: Prof. dr. Thijs Weststeijn Second reader: Prof. dr. Els Stronks Date: 10 July 2019 Title page illustration: Roemer Visscher, Emblem V, Sinnepoppen, I. Amsterdam, by W. Iansz., 1614, p. 5., shelfmark: OTM: OK 62-9148. Collection of Allard Pierson. 1 Table of Contents Introduction 4 Why study the tulip in Dutch emblem books? 4 Relevance to the Field 7 Research Questions 8 Theoretical Context 9 Methodology 20 Chapter Overview 23 Chapter 1: What is the historiography relating to the symbolic function of the tulip in seventeenth-century Dutch art? 24 1.1 The Emergence of Emblematics 24 1.2 Tulip Symbolism in Dutch Flower Paintings 26 1.3 Confusing Accounts: The Phases of the Tulipmania 29 Chapter 2: The Tulip as a Symbol of Virtue 39 2.1 Devotion 39 2.2 Chastity and Honorable Industry 44 2.3 The Multiplicity of Creation 49 Chapter 3: The Tulip as a Symbol of Vice in Roemer Visscher’s Sinnepoppen 57 3.1 Pre-iconographic Analysis 57 3.2 Iconographic Analysis 58 3.3 Iconological Analysis 61 Conclusion 70 Images 73 Appendix: List of Tulips in Dutch Emblem Books (1600-1700), in chronological order 84 Bibliography 105 2 Acknowledgements Writing this thesis has been the largest undertaking of my life. First, thanks are due to my thesis supervisor, prof. dr. Thijs Weststeijn, for assisting me with this, my first, thesis. -

De Gedichten

De gedichten Maria Tesselschade Roemers Visscher editie A. Agnes Sneller en Olga van Marion (met medewerking van Netty van Megen) bron A. Agnes Sneller en Olga van Marion (ed.), De gedichten van Tesselschade Roemers. Verloren, Hilversum 1994 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/viss002gedi01_01/colofon.htm © 2001 dbnl / A. Agnes Sneller, Olga van Marion 7 Voorwoord Een reeks van mensen heeft met ons meegelezen en materiaal voor de uitgave geleverd. Wij danken hiervoor drs. Ingrid Biesheuvel, Esther van Bijsterveld, dr. Ton Harmsen, Puck Hundepool, Babs Martens, Karin Pierens, Boukje Thijs, drs. Hans Verstraate, drs. Ingrid Weekhout en dr. Ton van der Wouden. Het werk van drs. Elizabeth Bouman, renaissancist, drs. Johan Koppenol, universitair docent oudere letterkunde RUG, drs. Dick van der Mark, renaissancist, en dr. Marijke Mooijaart, redacteur WNT, kon gebruikt worden om een definitieve vorm voor de bundel vast te stellen. Drs. Erna van Koeven stelde haar afstudeerscriptie beschikbaar. Dr. Wim Hüsken wees op het onuitgegeven handschrift van dr. P. Leendertz Jr. Dr. Louis Grijp leverde een bijdrage over de muzikale activiteiten van de dichter. de redactie herfst 1994 Maria Tesselschade Roemers Visscher, De gedichten 8 Tekening van H. Goltzius. Portret van een jonge vrouw (ca. 1605). Amsterdams Historisch Museum. Maria Tesselschade Roemers Visscher, De gedichten 9 Inleiding In de literatuurwetenschap bestaat het besef dat er geen oorzakelijke samenhang behoeft te zijn tussen het niveau van een auteur en de reputatie die deze geniet. Er zijn voortreffelijke eenlingen geweest onder de schrijvers die in bijna volstrekte vergetelheid zijn geraakt en anderzijds houdt de reputatie van sommigen niet noodzakelijk in dat hun verzen of verhalen van uitzonderlijke kwaliteit zijn (Sötemann 1994: 146). -

Consuls, Corsairs, and Captives: the Creation of Dutch Diplomacy in The

University of Miami Scholarly Repository Open Access Dissertations Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2012-11-21 Consuls, Corsairs, and Captives: the Creation of Dutch Diplomacy in the Early Modern Mediterranean, 1596-1699 Erica Heinsen-Roach University of Miami, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlyrepository.miami.edu/oa_dissertations Recommended Citation Heinsen-Roach, Erica, "Consuls, Corsairs, and Captives: the Creation of Dutch Diplomacy in the Early Modern Mediterranean, 1596-1699" (2012). Open Access Dissertations. 891. https://scholarlyrepository.miami.edu/oa_dissertations/891 This Embargoed is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at Scholarly Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI CONSULS, CORSAIRS, AND CAPTIVES: THE CREATION OF DUTCH DIPLOMACY IN THE EARLY MODERN MEDITERRANEAN, 1596-1699 By Erica Heinsen-Roach A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Miami in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Coral Gables, Florida December 2012 ©2012 Erica Heinsen-Roach All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy CONSULS, CORSAIRS, AND CAPTIVES: THE CREATION OF DUTCH DIPLOMACY IN THE EARLY MODERN MEDITERRANEAN, 1596-1699 Erica Heinsen-Roach Approved: ________________ _________________ Mary Lindemann, Ph.D. M. Brian Blake, Ph.D. Professor of History Dean of the Graduate School ________________ _________________ Hugh Thomas, Ph.D. Ashli White, Ph.D. Professor of History Professor of History ________________ Frank Palmeri, Ph.D. -

Alcohol, Tobacco, and the Intoxicated Social Body in Dutch Painting

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2-24-2014 Sobering Anxieties: Alcohol, Tobacco, and the Intoxicated Social Body in Dutch Painting During the True Freedom, 1650-1672 David Beeler University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Scholar Commons Citation Beeler, David, "Sobering Anxieties: Alcohol, Tobacco, and the Intoxicated Social Body in Dutch Painting During the True Freedom, 1650-1672" (2014). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4983 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sobering Anxieties: Alcohol, Tobacco, and the Intoxicated Social Body in Dutch Painting During the True Freedom, 1650-1672 by David Beeler A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Annette Cozzi, Ph.D. Cornelis “Kees” Boterbloem, Ph.D. Brendan Cook, Ph.D. Date of Approval: February 24, 2014 Keywords: colonialism, foreign, otherness, maidservant, Burgher, mercenary Copyright © 2014, David Beeler Table of Contents List of Figures .................................................................................................................................ii -

Het Muiderslot Het

Het Muiderslot Het Muiderslot - Beleef zeven eeuwen geschiedenis in het echt! Het Muiderslot heeft de afgelopen zeven eeuwen heel wat meegemaakt: van ridders, graaf Floris, samenzweringen, slimme bouwtrucs en martelingen tot literaire feesten, P.C. Hooft, dichters en Het Muiderslot kunstenaars, vrolijk gezang, oorlogen, overstromingen, sloop en renovatie en de geleidelijke groei naar een volwaardig Rijksmuseum. Lees over de vele indrukwekkende hoogte- en dieptepunten in de roerige Beleef zeven eeuwen geschiedenis in het echt! geschiedenis van dit mooiste middeleeuwse kasteel van Nederland. Beleef zeven eeuwen geschiedenis in het geschiedenis eeuwen echt! Beleef zeven www.muiderslot.nl Annick Huijbrechts & Yvonne Molenaar Het Muiderslot Beleef zeven eeuwen geschiedenis in het echt! Annick Huijbrechts & Yvonne Molenaar © 2013 Stichting Rijksmuseum Muiderslot Colofon Partners Auteur: Annick Huijbrechts (Turtle Art) Deze uitgave is mogelijk gemaakt met steun van: Tekst- en beeldinbreng: Yvonne Molenaar Tekstredactie: Ida Schuurman Vormgeving: Endeloos Grafisch Ontwerp Fotografie: Mike Bink, Kropot en Endeloos Grafisch Ontwerp © 2013 Stichting Rijksmuseum Muiderslot 0 Inleiding: de roerige geschiedenis van het Muiderslot 5 Zeven eeuwen vol trots, tragiek en temperament 1 Floris de Vijfde – de held van het volk 8 Grondlegger van het Muiderslot 2 Het mooiste middeleeuwse kasteel van Nederland 14 De bouw van het Muiderslot Inhoud 3 Vernuftig bouwwerk vol onaangename verrassingen 19 Muiderslot als verdedigingsburcht 4 Er was eens… een romantisch -

PDF (Nellen, Petronella Moens Over Hugo De Groot)

MOENSIANA nummer 10 september 2013 Petronella Moens en haar vaderlandse helden een uitgave van Moensiana Nr 10 - september 2013 Petronella Moens en haar vaderlandse helden. Van de redactie Moensiana, de jaarlijkse nieuwsbrief van de Stichting Petronella Moens, De Vriendin van ‘t Vaderland beleeft in 2013 zijn tiende jaargang. Met deze aflevering van Moensiana, gevuld met een viertal artikelen rond het thema ‘Petronella Moens en haar vaderlandse helden’, willen wij het tweede lustrum kleur geven. Behalve de nieuwsberichten over Petronella Moens en het aan haar gewijde onderzoek, die u kunt terugvinden in de rubriek Varia aan het einde van deze nieuwsbrief, brengen wij een aantal artikelen waarin het gaat om de visie op helden als Hugo de Groot en de gebroeders De Witt, zoals Petronella Moens en haar goede vriend Adriaan Loosjes die in poëzie en proza verwoordden. Het herdenkingsjaar 1813 vormt een gerede aanleiding om de positie van Petronella Moens in dat jaar en in de woelige decennia daarvoor nader te bepalen. Waar stond Petronella in 1813 en hoe heeft zij in haar publicaties gereageerd op de jaren van revolutie en contra-revolutie? Die laatste vragen komen aan de orde in de bijdrage van Ans Veltman. Zij laat zien hoe Petronella Moens in de jaren van de Bataafse Omwenteling haar plaats trachtte te vinden. Henk Nellen, kenner van Hugo de Groot bij uitstek, laat zijn licht schijnen over het boek Hugo de Groot in zeven zangen (1790) van Petronella Moens. Over De Gebroeders De Witten (1791) van Moens gaat de bijdrage van Peter Altena. Ook Adriaan Loosjes, tijdgenoot en vriend van Petronella Moens, schreef over de zo beestachtig vermoorde broers, in zijn roman Johan de Witt, raadpensionaris van Holland (1805) en in een treurspel uit 1807. -

Download PDF Van Tekst

Gedichten Jacob Westerbaen Editie Johan Koppenol bron Jacob Westerbaen, Gedichten (ed. Johan Koppenol). Athenaeum - Polak & Van Gennep, Amsterdam 2001 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/west001gedi05_01/colofon.php © 2016 dbnl / Johan Koppenol 7 Minnedichten Jacob Westerbaen, Gedichten 9 De verhuizing van Cupido (fragmenten) aant. Jupiter viert zijn verjaardagsfeestje op de Olympus. Helaas gooit twistgodin Eris roet in het eten, of eigenlijk gif in de wijn... Zo haast als deze wijn was in het lijf gegoten, heeft het vergif zijn kracht straks naar het hart geschoten, om dat te roeren om, en halen voor de dag al 't geen dat van tevoor wel diep gerekend lag. 5 De zalen werden stil, de een begon te morren en op de anderen al morrende te knorren; men zag 't en was geen deeg, en dat het honden zou, doch niemand liet de gek nog kijken uit de mouw. Maar als het met de wijn omhoog begon te trekken 10 en in der goden brein zijn krachten uit te strekken en Bacchus uit hun hoofd de gulden rede stal, toen ving het kijven aan, en 't werd geheel van 't mal. Gelijk een heim'lijk vuur, dat weinig van te voren in een besloten huis zichzelve scheen te smoren, 15 wanneer het raakt omhoog en in de daken slaat, zijn vlammen overal aan ieder kijken laat, zo toont het twistvenijn zijn onbeschofte vlagen, nu 't in de hersenpan der goden is geslagen. Nu is er dam, noch dijk, noch sluis, noch slot, noch wal 20 die iemand van de goôn het bakkes sluiten zal. -

Vroomen Geboren Te Zwijndrecht

Taal van de Republiek Het gebruik van vaderlandretoriek in Nederlandse pamfletten, 1618-1672 The Language of the Republic The Rhetoric of Fatherland in Dutch Pamphlets, 1618-1672 Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam op gezag van de rector magnificus Prof.dr. H.G. Schmidt en volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties. De openbare verdediging zal plaatsvinden op dinsdag 15 mei 2012 om 13.30 uur door Ingmar Henrik Vroomen geboren te Zwijndrecht Promotiecommissie Promotor: Prof.dr. R.C.F. von Friedeburg Overige leden: Prof.dr. H.J.M. Nellen Prof.dr. J.S. Pollmann Prof.dr. N.C.F. van Sas ii Inhoudsopgave Woord vooraf v Afkortingen vi 1. Inleiding 1 1.1 Introductie 1 1.2. Historiografie, patria en patriotten 4 Nederlandse nationale geschiedenis 4 De ‘canon van het modernisme’ 8 Office en patriot 12 De herkomst van vaderland 16 Patriottisme in de zeventiende-eeuwse Republiek 20 1.3 Onderzoek en methode 26 De Nederlandse Republiek 1618-1672: drie crises, vier jaren 26 Bronnen en analyse 29 2. De fundamenten van het vaderland – 1618-1619: De Bestandstwisten 35 2.1 Introductie 35 Onderzoekscorpus 38 2.2 Achtergrond 41 Het Twaalfjarig Bestand (1609-1621) 41 Maurits en Oldenbarnevelt 45 Arminianen en gomaristen 50 1610-1617: Naar de breuk 55 2.3 1618: Climax 59 Onrust in Hollandse steden: Leiden, Oudewater, Haarlem 61 De ‘grooten pensionaris’ en de Barneveltse Ligue 75 Maurits grijpt in 93 2.4 1619: Winnaars en verliezers 102 De Nationale Synode 102 De executie van Oldenbarnevelt 106 Remonstranten in het nauw 109 2.5 Conclusie 114 3. -

Landsadvocaat Van Oldenbarnevelt 3

Nummer Toegang: 3.01.14 Inventaris van het archief van Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, 1586-1619 Versie: 15-08-2019 H.J.Ph.G. Kaajan Nationaal Archief, Den Haag 1984 This finding aid is written in Dutch. 3.01.14 Landsadvocaat Van Oldenbarnevelt 3 INHOUDSOPGAVE Beschrijving van het archief.....................................................................................13 Aanwijzingen voor de gebruiker...............................................................................................14 Openbaarheidsbeperkingen......................................................................................................14 Beperkingen aan het gebruik....................................................................................................14 Materiële beperkingen..............................................................................................................14 Aanvraaginstructie.................................................................................................................... 14 Citeerinstructie.......................................................................................................................... 14 Archiefvorming..........................................................................................................................15 Geschiedenis van de archiefvormer..........................................................................................15 A Geschiedenis..................................................................................................................... -

The Netherlands

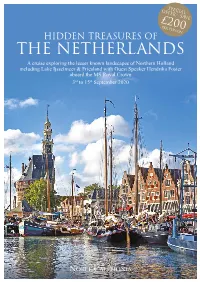

SPECIAL OFFER - SAVE £200 PER PERSON HIDDEN TREASURES OF THE NETHERLANDS A cruise exploring the lesser known landscapes of Northern Holland including Lake Ijsselmeer & Friesland with Guest Speaker Hendrika Foster aboard the MS Royal Crown 3rd to 15th September 2020 The historic town of Enkhuizen oin the MS Royal Crown in Haarlem and discover the rural tranquillity of The Netherland’s northernmost provinces. Along our route we will explore NORTH Franeker J SEA Leeuwarden the rich history and unique flora and fauna of this peaceful and unspoilt area, Harlingen Alkmaar Friesland Hoorn Lemmer visit its picturesque towns and villages and encounter highlights of the region’s Edam & Marken Enkhuizen Haarlem glorious maritime past, and present. This is true Holland as the native Dutch Amsterdam De Weerribben- Wieden NP would describe it. Lelystad THE NETHERLANDS Rhine Our journey begins in delightful Haarlem which today still retains much of its Medieval character of gabled houses and cobbled streets. We then cruise north CZECH to discover the shores of the Zuiderzee, sailing across the Ijsselmeer, the largest REPUBLIC freshwater lake in The Netherlands. We will spend some time in the ancient seaport of Harlingen, with its FRANCE SLOVAKIA age-old merchant houses, canals and atmospheric inner harbours, from where we can visit nearby Leeuwarden,Rhine famous as the birthplace of the World War I spy, Mata Hari. Also included are visits to the Afsluitdijk, Europe’s DANUBE BEND longest dam, the Woudagemaal Steam Pumping Station and Batavia Shipyard, all great testaments to the AUSTRIA HUNGARY immense engineering and building achievements of the Dutch nation. -

University of Dundee Confiscated Manuscripts and Books Van Ittersum, Martine Julia

University of Dundee Confiscated Manuscripts And Books Van Ittersum, Martine Julia Published in: Lost Books DOI: 10.1163/9789004311824_018 Publication date: 2016 Licence: CC BY-NC-ND Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Discovery Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Van Ittersum, M. J. (2016). Confiscated Manuscripts And Books: What Happened to the Personal Library and Archive of Hugo Grotius Following His Arrest on Charges of High Treason in August 1618? In F. Bruni, & A. Pettegree (Eds.), Lost Books: Reconstructing the Print World of Pre-Industrial Europe (pp. 362-385). (Library of the Written Word; Vol. 46). Brill Academic Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004311824_018 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in Discovery Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from Discovery Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 chapter 17 Confiscated Manuscripts and Books: What Happened to the Personal Library and Archive of Hugo Grotius Following His Arrest on Charges of High Treason in August 1618? Martine Julia van Ittersum Mindful of his own mortality, Hugo Grotius (1583–1645) wrote to his younger brother in March 1643 that he was preparing a set of manuscripts – “for the writing of which God created me in the first place” – for publication by his heirs. -

4. Persoons- En Plaatsnamenregister. Index Op De Delen I-Xvii Van De Briefwisseling Van Hugo Grotius

4. PERSOONS- EN PLAATSNAMENREGISTER. INDEX OP DE DELEN I-XVII VAN DE BRIEFWISSELING VAN HUGO GROTIUS De Romeinse cijfers verwijzen naar de `Lijst van geciteerde plaatsen´ en het `Register van persoonsnamen, aardrijkskundige namen en boektitels´ in de afzonderlijke delen Aa (Aha), rivier: XV Aa., Anthony Willemsz. van der: IV, V, XVII Aa, echtgenote van Anthony Willemsz: zie Walenburch, Adriana Pietersdochter van Aarau (Aro): VII, IX-XII, XIV, XV, XVII Aardenburg: XII Aare: X Aargau: X-XII Aarlanderveen: I, IV Aarlanderveen, heer van: zie Nooms, Willem Aarschot: VI Aarschot, hertog van: zie Aremberg, Philips Karel van Aartshertogen: zie Albert (Albrecht) van Oostenrijk, Isabella van Oostenrijk Abarbanel: zie Abravanel, Isaac Abascantus: IX Abbas I, sjah: X, XVII Abbas II, sjah: XI, XIV, XV, XVI Abbatia Heijllesema: VI Abbatisvilla: zie Abbeville Abbazel: zie Appenzell Abbé, d´: zie Labbé, Charles Abbekerk: IV Abbenbroek: I Abbesteech, mijnheer van: V Abbesteech, Barthout van: XII Abbesteech, Pauwels van: XII Abbesteegh, Willem van: VI, VII, VIII Abbeville (Abbevilla): V, VI, VII, IX-XII Abbiategrasso: VII Abbot, George, aartsbisschop van Canterbury: I, III-V, XVI, XVII Abbot, Maurice: I, XVII Abbot, Robert, bisschop van Salisbury: I, II, VI Abcoude: XV Abdallah ibn Abi-l-Yasir ibn Abi-l-Makarim ibn al-Amid: IV Abegg, Johann Christoph: XVI Abenada: XII Abenestra(s): zie Abraham ibn Ezra Aberdeen (Aberdeenshire): IX, X, XV, XVI Aberdeen, bisschop van: zie Bannatyne, Adam Abernethy, John, bisschop van Caithness: X, XI Abessinië (Abyssinië;