The Impact of Change Agents on Southern Sudan History, ١٨٩٨ – ١٩٧٣

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No More Hills Ahead?

No More Hills Ahead? The Sudan’s Tortuous Ascent to Heights of Peace Emeric Rogier August 2005 NETHERLANDS INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS CLINGENDAEL CIP-Data Koninklijke bibliotheek, The Hague Rogier, Emeric No More Hills Ahead? The Sudan’s Tortuous Ascent to Heights of Peace / E. Rogier – The Hague, Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. Clingendael Security Paper No. 1 ISBN 90-5031-102-4 Language-editing by Rebecca Solheim Desk top publishing by Birgit Leiteritz Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael Clingendael Security and Conflict Programme Clingendael 7 2597 VH The Hague Phonenumber +31(0)70 - 3245384 Telefax +31(0)70 - 3282002 P.O. Box 93080 2509 AB The Hague E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.clingendael.nl The Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael is an independent institute for research, training and public information on international affairs. It publishes the results of its own research projects and the monthly ‘Internationale Spectator’ and offers a broad range of courses and conferences covering a wide variety of international issues. It also maintains a library and documentation centre. © Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyrightholders. Clingendael Institute, P.O. Box 93080, 2509 AB The Hague, The Netherlands. Contents Foreword i Glossary of Abbreviations iii Executive Summary v Map of Sudan viii Introduction 1 Chapter 1 The Sudan: A State of War 5 I. -

The Mount Scopus Enclave, 1948–1967

Yfaat Weiss Sovereignty in Miniature: The Mount Scopus Enclave, 1948–1967 Abstract: Contemporary scholarly literature has largely undermined the common perceptions of the term sovereignty, challenging especially those of an exclusive ter- ritorial orientation and offering a wide range of distinct interpretations that relate, among other things, to its performativity. Starting with Leo Gross’ canonical text on the Peace of Westphalia (1948), this article uses new approaches to analyze the policy of the State of Israel on Jerusalem in general and the city’s Mount Scopus enclave in 1948–1967 in particular. The article exposes tactics invoked by Israel in three different sites within the Mount Scopus enclave, demilitarized and under UN control in the heart of the Jordanian-controlled sector of Jerusalem: two Jewish in- stitutions (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Hadassah hospital), the Jerusa- lem British War Cemetery, and the Palestinian village of Issawiya. The idea behind these tactics was to use the Demilitarization Agreement, signed by Israel, Transjor- dan, and the UN on July 7, 1948, to undermine the status of Jerusalem as a Corpus Separatum, as had been proposed in UN Resolution 181 II. The concept of sovereignty stands at the center of numerous academic tracts written in the decades since the end of the Cold War and the partition of Europe. These days, with international attention focused on the question of Jerusalem’s international status – that is, Israel’s sovereignty over the town – there is partic- ularly good reason to examine the broad range of definitions yielded by these discussions. Such an examination can serve as the basis for an informed analy- sis of Israel’s policy in the past and, to some extent, even help clarify its current approach. -

Shilluk Lexicography with Audio Data Bert Remijsen, Otto Gwado Ayoker & Amy Martin

Shilluk Lexicography With Audio Data Bert Remijsen, Otto Gwado Ayoker & Amy Martin Description This archive represents a resource on the lexicon of Shilluk, a Nilo-Saharan language spoken in South Sudan. It includes a table of 2530 lexicographic items, plus 10082 sound clips. The table is included in pdf and MS Word formats; the sound clips are in wav format (recorded with Shure SM10A headset mounted microphone and and Marantz PMD 660/661 solid state recorder, at a sampling frequency of 48kHz and a bit depth of 16). For each entry, we present: (a) the entry form (different for each word class, as explained below); (b) the orthographic representation of the entry form; (c) the paradigm forms and/or example(s); and (d) a description of the meaning. This collection was built up from 2013 onwards. The majority of entries were added between 2015 and 2018, in the context of the project “A descriptive analysis of the Shilluk language”, funded by the Leverhulme Trust (RPG-2015- 055). The main two methods through which the collection was built up are focused lexicography collection by semantic domain, whereby we would collect e.g. words relating to dwellings / fishing / etc., and text collection, whereby we would add entries as we came across new words in the course of the analysis of narrative text. We also added some words on the basis of two earlier lexicographic studies on Shilluk: Heasty (1974) and Ayoker & Kur (2016). We estimate that we drew a few hundred words from each. Comparing the lexicography resource presented here with these two resources, our main contribution is detail, in that we present information on the phonological form and on the grammatical paradigm. -

A History of Money in Palestine: from the 1900S to the Present

A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Mitter, Sreemati. 2014. A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12269876 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present A dissertation presented by Sreemati Mitter to The History Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts January 2014 © 2013 – Sreemati Mitter All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Roger Owen Sreemati Mitter A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present Abstract How does the condition of statelessness, which is usually thought of as a political problem, affect the economic and monetary lives of ordinary people? This dissertation addresses this question by examining the economic behavior of a stateless people, the Palestinians, over a hundred year period, from the last decades of Ottoman rule in the early 1900s to the present. Through this historical narrative, it investigates what happened to the financial and economic assets of ordinary Palestinians when they were either rendered stateless overnight (as happened in 1948) or when they suffered a gradual loss of sovereignty and control over their economic lives (as happened between the early 1900s to the 1930s, or again between 1967 and the present). -

Loyal to Israel: Transnational Solidarity with the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict

LOYAL TO ISRAEL: TRANSNATIONAL SOLIDARITY WITH THE ISRAELI- PALESTINIAN CONFLICT A STUDY OF LOYALIST TRANSNATIONAL SOLIDARITY WITH ISRAEL 1 Loyal to Israel: Transnational solidarity with the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Thesis MA Modern Middle East Studies Leiden University Andrew Graham Robertson Page Student number: 1963023 15 January 2018 Supervisor: Dr. Noa Schonmann Words: 21,676 Cover Photo: Adrian McKinty, “Israeli flags in Belfast”, Adrian McKinty Blogspot, accessed January 14, 2018, http://adrianmckinty.blogspot.nl/2015/04/the-israeli-flags-in-belfast.html. Abstract: The Ulster Loyalist community of Northern Ireland have long regarded themselves as a people besieged by Irish Republican ideology. While lacking international support, the Loyalists have formed a geographically and culturally unusual bond with the State of Israel. Loyalist support for Israel increased visibly during the 2002 Intifada and Loyalists continue to make declarations of support for Israel. Yet, the governing Likud Party in recent years has commemorated Zionist insurgents, who committed acts of terror against the British administration in the 1940s. The Israeli government’s actions have led to criticism from the Her Majesty’s British government, which the Loyalist community aims to stand alongside, to maintain the Union and prevent the triumph of Irish Republicanism. Despite British public support for Israel declining during the past few decades, Ulster Loyalist support for the Jewish State is believed to be one of the strongest in Europe. 2 Contents Page -

The Criminalization of South Sudan's Gold Sector

The Criminalization of South Sudan’s Gold Sector Kleptocratic Networks and the Gold Trade in Kapoeta By the Enough Project April 2020* A Precious Resource in an Arid Land Within the area historically known as the state of Eastern Equatoria, Kapoeta is a semi-arid rangeland of clay soil dotted with short, thorny shrubs and other vegetation.1 Precious resources lie below this desolate landscape. Eastern Equatoria, along with the region historically known as Central Equatoria, contains some of the most important and best-known sites for artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASM). Some estimates put the number of miners at 60,000 working at 80 different locations in the area, including Nanaknak, Lauro (Didinga Hills), Napotpot, and Namurnyang. Locals primarily use traditional mining techniques, panning for gold from seasonal streams in various villages. The work provides miners’ families resources to support their basic needs.2 Kapoeta’s increasingly coveted gold resources are being smuggled across the border into Kenya with the active complicity of local and national governments. This smuggling network, which involves international mining interests, has contributed to increased militarization.3 Armed actors and corrupt networks are fueling low-intensity conflicts over land, particularly over the ownership of mining sites, and causing the militarization of gold mining in the area. Poor oversight and conflicts over the control of resources between the Kapoeta government and the national government in Juba enrich opportunistic actors both inside and outside South Sudan. Inefficient regulation and poor gold outflows have helped make ASM an ideal target for capture by those who seek to finance armed groups, perpetrate violence, exploit mining communities, and exacerbate divisions. -

RVI Local Peace Processes in Sudan.Pdf

Rift Valley Institute ﻤﻌﻬﺪ اﻷﺨدود اﻟﻌﻇﻴم Taasisi ya Bonde Kuu ySMU vlˆ yU¬T tí Machadka Dooxada Rift 东非大裂谷研究院 Institut de la Vallée du Rift Local Peace Processes in Sudan A BASELINE STUDY Mark Bradbury John Ryle Michael Medley Kwesi Sansculotte-Greenidge Commissioned by the UK Government Department for International Development “Our sons are deceiving us... … Our soldiers are confusing us” Chief Gaga Riak Machar at Wunlit Dinka-Nuer Reconciliation Conference 1999 “You, translators, take my words... It seems we are deviating from our agenda. What I expected was that the Chiefs of our land, Dinka and Nuer, would sit on one side and address our grievances against the soldiers. I differ from previous speakers… I believe this is not like a traditional war using spears. In my view, our discussion should not concentrate on the chiefs of Dinka and Nuer, but on the soldiers, who are the ones who are responsible for beginning this conflict. “When John Garang and Riek Machar [leaders of rival SPLA factions] began fighting did we understand the reasons for their fighting? When people went to Bilpam [in Ethiopia] to get arms, we thought they would fight against the Government. We were not expecting to fight against ourselves. I would like to ask Commanders Salva Mathok & Salva Kiir & Commander Parjak [Senior SPLA Commanders] if they have concluded the fight against each other. I would ask if they have ended their conflict. Only then would we begin discussions between the chiefs of Dinka and Nuer. “The soldiers are like snakes. When a snake comes to your house day after day, one day he will bite you. -

Professionalizing Science: British Geography, Africa, and the Exploration of the Nile Miguel Angel Chavez Vanderbilt University

Professionalizing Science: British Geography, Africa, and the Exploration of the Nile Miguel Angel Chavez Vanderbilt University February 2019 Dissertation Prospectus Prepared for the Doctoral Committee: Dr. Lauren Benton Dr. Moses Ochonu Dr. James Epstein Dr. Jonathan Lamb 1 Abstract: This dissertation identifies the mid-nineteenth century as an inflection point in the practice, organization, and perception of science in Britain. In assessing the history of British exploration in Africa, I investigate how a new generation of explorers overcame social and economic barriers that limited scientific work to gentlemen scientists. I examine the strategies employed by explorers to bolster their scientific credentials, such as a commitment to accurate measurements; a reliance on learned institutions such as the Royal Geographical Society to confer scientific and financial capital on explorers; and a devotion to ideologies prevalent in British geographic circles such as abolitionism and the holistic description of the world. By investigating how these strategies occurred in the context of Nile exploration, I connect the issue of the professionalization of geography with questions of empire, indigenous knowledge, and the transnational nature of British geography. Finally, I chart the development of geography from its seeming unity with the establishment of the Royal Geographical Society to the division of the field between academic geographers and field scientists. It is my hope this study can assess how the legacy of Nile exploration helped transform science in the nineteenth century and reframe the relationship between science and society. Introduction Two strands of inquiry have dominated histories of science in the long nineteenth century. Assessing how class, education, and networks influenced scientific knowledge production and highlighting the natural sciences, one set of historians has placed the gentlemanly scientist at the center of British science from the seventeenth century through the mid-nineteenth century. -

Map of South Sudan

UNITED NATIONS SOUTH SUDAN Geospatial 25°E 30°E 35°E Nyala Ed Renk Damazin Al-Fula Ed Da'ein Kadugli SUDAN Umm Barbit Kaka Paloich Ba 10°N h Junguls r Kodok Āsosa 10°N a Radom l-A Riangnom UPPER NILEBoing rab Abyei Fagwir Malakal Mayom Bentiu Abwong ^! War-Awar Daga Post Malek Kan S Wang ob Wun Rog Fangak at o Gossinga NORTHERN Aweil Kai Kigille Gogrial Nasser Raga BAHR-EL-GHAZAL WARRAP Gumbiel f a r a Waat Leer Z Kuacjok Akop Fathai z e Gambēla Adok r Madeir h UNITY a B Duk Fadiat Deim Zubeir Bisellia Bir Di Akobo WESTERN Wau ETHIOPIA Tonj Atum W JONGLEI BAHR-EL-GHAZAL Wakela h i te LAKES N Kongor CENTRAL Rafili ile Peper Bo River Post Jonglei Pibor Akelo Rumbek mo Akot Yirol Ukwaa O AFRICAN P i Lol b o Bor r Towot REPUBLIC Khogali Pap Boli Malek Mvolo Lowelli Jerbar ^! National capital Obo Tambura Amadi WESTERN Terakeka Administrative capital Li Yubu Lanya EASTERN Town, village EQUATORIAMadreggi o Airport Ezo EQUATORIA 5°N Maridi International boundary ^! Juba Lafon Kapoeta 5°N Undetermined boundary Yambio CENTRAL State (wilayah) boundary EQUATORIA Torit Abyei region Nagishot DEMOCRATIC Roue L. Turkana Main road (L. Rudolf) Railway REPUBLIC OF THE Kajo Yei Opari Lofusa 0 100 200km Keji KENYA o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o 0 50 100mi CONGO o e The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

The Role of Indigenous Languages in Southern Sudan: Educational Language Policy and Planning

The Role of Indigenous Languages in Southern Sudan: Educational Language Policy and Planning H. Wani Rondyang A thesis submitted to the Institute of Education, University of London, for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2007 Abstract This thesis aims to questions the language policy of Sudan's central government since independence in 1956. An investigation of the root causes of educational problems, which are seemingly linked to the current language policy, is examined throughout the thesis from Chapter 1 through 9. In specific terms, Chapter 1 foregrounds the discussion of the methods and methodology for this research purposely because the study is based, among other things, on the analysis of historical documents pertaining to events and processes of sociolinguistic significance for this study. The factors and sociolinguistic conditions behind the central government's Arabicisation policy which discourages multilingual development, relate the historical analysis in Chapter 3 to the actual language situation in the country described in Chapter 4. However, both chapters are viewed in the context of theoretical understanding of language situation within multilingualism in Chapter 2. The thesis argues that an accommodating language policy would accord a role for the indigenous Sudanese languages. By extension, it would encourage the development and promotion of those languages and cultures in an essentially linguistically and culturally diverse and multilingual country. Recommendations for such an alternative educational language policy are based on the historical and sociolinguistic findings in chapters 3 and 4 as well as in the subsequent discussions on language policy and planning proper in Chapters 5, where theoretical frameworks for examining such issues are explained, and Chapters 6 through 8, where Sudan's post-independence language policy is discussed. -

Clanship, Conflict and Refugees: an Introduction to Somalis in the Horn of Africa

CLANSHIP, CONFLICT AND REFUGEES: AN INTRODUCTION TO SOMALIS IN THE HORN OF AFRICA Guido Ambroso TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I: THE CLAN SYSTEM p. 2 The People, Language and Religion p. 2 The Economic and Socials Systems p. 3 The Dir p. 5 The Darod p. 8 The Hawiye p. 10 Non-Pastoral Clans p. 11 PART II: A HISTORICAL SUMMARY FROM COLONIALISM TO DISINTEGRATION p. 14 The Colonial Scramble for the Horn of Africa and the Darwish Reaction (1880-1935) p. 14 The Boundaries Question p. 16 From the Italian East Africa Empire to Independence (1936-60) p. 18 Democracy and Dictatorship (1960-77) p. 20 The Ogaden War and the Decline of Siyad Barre’s Regime (1977-87) p. 22 Civil War and the Disintegration of Somalia (1988-91) p. 24 From Hope to Despair (1992-99) p. 27 Conflict and Progress in Somaliland (1991-99) p. 31 Eastern Ethiopia from Menelik’s Conquest to Ethnic Federalism (1887-1995) p. 35 The Impact of the Arta Conference and of September the 11th p. 37 PART III: REFUGEES AND RETURNEES IN EASTERN ETHIOPIA AND SOMALILAND p. 42 Refugee Influxes and Camps p. 41 Patterns of Repatriation (1991-99) p. 46 Patterns of Reintegration in the Waqoyi Galbeed and Awdal Regions of Somaliland p. 52 Bibliography p. 62 ANNEXES: CLAN GENEALOGICAL CHARTS Samaal (General/Overview) A. 1 Dir A. 2 Issa A. 2.1 Gadabursi A. 2.2 Isaq A. 2.3 Habar Awal / Isaq A.2.3.1 Garhajis / Isaq A. 2.3.2 Darod (General/ Simplified) A. 3 Ogaden and Marrahan Darod A. -

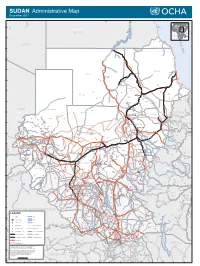

SUDAN Administrative Map December 2011

SUDAN Administrative Map December 2011 Faris IQLIT Ezbet Dush Ezbet Maks el-Qibli Ibrim DARAW KOM OMBO Al Hawwari Al-Kufrah Nagel-Gulab ASWAN At Tallab 24°N EGYPT 23°N R E LIBYA Halaib D S 22°N SUDAN ADMINISTRATED BY EGYPT Wadi Halfa E A b 'i Di d a i d a W 21°N 20°N Kho r A bu Sun t ut a RED SEA a b r A r o Porth Sudan NORTH Abu Hamad K Dongola Suakin ur Qirwid m i A ad 19°N W Bauda Karima Rauai Taris Tok ar e il Ehna N r e iv R RIVER NILE Ri ver Nile Desert De Bayouda Barbar Odwan 18°N Ed Debba K El Baraq Mib h o r Adara Wa B a r d a i Hashmet Atbara ka E Karora l Atateb Zalat Al Ma' M Idd Rakhami u Abu Tabari g a Balak d a Mahmimet m Ed Damer Barqa Gereis Mebaa Qawz Dar Al Humr Togar El Hosh Al Mahmia Alghiena Qalat Garatit Hishkib Afchewa Seilit Hasta Maya Diferaya Agra 17°N Anker alik M El Ishab El Hosh di El Madkurab Wa Mariet Umm Hishan Qalat Kwolala Shendi Nakfa a r a b t Maket A r a W w a o d H i i A d w a a Abdullah Islandti W b Kirteit m Afabet a NORTH DARFUR d CHAD a Zalat Wad Tandub ug M l E i W 16°N d Halhal Jimal Wad Bilal a a d W i A l H Aroma ERITREA Keren KHARTOUM a w a KASSALA d KHARTOUM Hagaz G Sebderat Bahia a Akordat s h Shegeg Karo Kassala Furawiya Wakhaim Surgi Bamina New Halfa Muzbat El Masid a m a g Barentu Kornoi u Malha Haikota F di Teseney Tina Um Baru El Mieiliq 15°N Wa Khashm El Girba Abu Quta Abu Ushar Tandubayah Miski Meheiriba EL GEZIRA Sigiba Rufa'ah Anka El Hasahisa Girgira NORTH KORDOFAN Ana Bagi Baashim/tina Dankud Lukka Kaidaba Falankei Abdel Shakur Um Sidir Wad Medani Sodiri Shuwak Badime Kulbus