A History of Money in Palestine: from the 1900S to the Present

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Secretariats of Roads Transportation Report 2015

Road Transportation Report: 2015. Category Transfer Fees Amount Owed To lacal Remained No. Local Authority Spent Amount Clearing Amount classification 50% Authorities 50% amount 1 Albireh Don’t Exist Municipality 1,158,009.14 1,158,009.14 0.00 1,158,009.14 2 Alzaytouneh Don’t Exist Municipality 187,634.51 187,634.51 0.00 187,634.51 3 Altaybeh Don’t Exist Municipality 66,840.07 66,840.07 0.00 66,840.07 4 Almazra'a Alsharqia Don’t Exist Municipality 136,262.16 136,262.16 0.00 136,262.16 5 Banizeid Alsharqia Don’t Exist Municipality 154,092.68 154,092.68 0.00 154,092.68 6 Beitunia Don’t Exist Municipality 599,027.36 599,027.36 0.00 599,027.36 7 Birzeit Don’t Exist Municipality 137,285.22 137,285.22 0.00 137,285.22 8 Tormos'aya Don’t Exist Municipality 113,243.26 113,243.26 0.00 113,243.26 9 Der Dibwan Don’t Exist Municipality 159,207.99 159,207.99 0.00 159,207.99 10 Ramallah Don’t Exist Municipality 832,407.37 832,407.37 0.00 832,407.37 11 Silwad Don’t Exist Municipality 197,183.09 197,183.09 0.00 197,183.09 12 Sinjl Don’t Exist Municipality 158,720.82 158,720.82 0.00 158,720.82 13 Abwein Don’t Exist Municipality 94,535.83 94,535.83 0.00 94,535.83 14 Atara Don’t Exist Municipality 68,813.12 68,813.12 0.00 68,813.12 15 Rawabi Don’t Exist Municipality 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 16 Surda - Abu Qash Don’t Exist Municipality 73,806.64 73,806.64 0.00 73,806.64 17 Hay Alkarama Don’t Exist Village Council 7,551.17 7,551.17 0.00 7,551.17 18 Almoghayar Don’t Exist Village Council 71,784.87 71,784.87 0.00 71,784.87 19 Alnabi Saleh Don’t Exist Village Council -

Jerusalem Chronology 2015 January Jan. 1: the Israeli Supreme Court

Jerusalem Chronology 2015 January Jan. 1: The Israeli Supreme Court rejects an appeal to prevent the demolition of the homes of four Palestinians from East Jerusalem who attacked Israelis in West Jerusalem in recent months. - Marabouts at Al-Aqsa Mosque confront a group of settlers touring Al-Aqsa compound. Jan. 3: Palestinian MK Ahmad Tibi joins hundreds of Palestinians marching toward the Al-Aqsa Mosque in the Old City of Jerusalem to mark the Prophet Muhammad's birthday. Jan. 5: Settlers tour Al-Aqsa Mosque compound while Israeli forces confiscate the IDs of Muslims trying to enter. - Around 50 Israeli forces along with 18 settlers tour Al-Aqsa compound. Jan. 8: A Jewish Israeli man is stabbed and injured by an unknown assailant while walking near the Old City’s Damascus Gate. Jan. 9: Israeli police detain at least seven Palestinians in a series of raids in the Old City over the stabbing a day earlier. - Yedioth Ahronoth reports that the Israeli Intelligence (Shabak) frustrated an operation that was intended to blow the Dome of the Rock by an American immigrant. Jan. 11: Israeli police forces detain seven Palestinians from Silwan after a settler vehicle was torched in the area. Jan. 12: A Jerusalem magistrate court has ruled that Israeli settlers who occupied Palestinian homes in East Jerusalem may not make substantial changes to the properties. - Settlers tour Al-Aqsa Mosque compound. Jan. 13: Israeli forces detained three 14-year old youth during a raid on Issawiyya and two women while leaving Al-Aqsa Mosque. Jan. 14: Jewish extremists morning punctured the tires of 11 vehicles in Beit Safafa. -

Beit Sahour City Profile

Beit Sahour City Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation Azahar Program 2010 Palestinian Localities Study Bethlehem Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project through the Azahar Program. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, village committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 1 Palestinian Localities Study Bethlehem Governorate Background This booklet is part of a series of booklets, which contain compiled information about each city, town, and village in Bethlehem Governorate. These booklets came as a result of a comprehensive study of all localities in Bethlehem Governorate, which aims at depicting the overall living conditions in the governorate and presenting developmental plans to assist in developing the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Village Profiles and Azahar Needs Assessment;" the project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) and the Azahar Program. The "Village Profiles and Azahar Needs Assessment" was designed to study, investigate, analyze and document the socio-economic conditions and the needed programs and activities to mitigate the impact of the current unsecure political, economic and social conditions in Bethlehem Governorate with particular focus on the Azahar program objectives and activities concerning water, environment, and agriculture. -

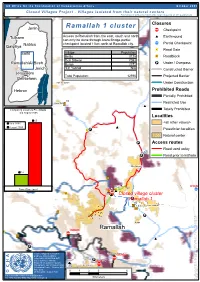

Ramallah 1 Cluster Closures Jenin ‚ Checkpoint

D UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs October 2005 º¹P Closed Villages Project - Villages isolated from their natural centers º¹P Palestinians without permits (the large majority of the population) /" ## Ramallah 1 cluster Closures Jenin ¬Ç Checkpoint ## Tulkarm AccessSalfit to Ramallah from the east, south and north Earthmound can only be done through Atara Bridge partial ¬Ç Nablus checkpoint located 11km north of Ramallah city. Partial Checkpoint Qalqiliya D Road## Gate Salfit Village Population Beitin 3125 /" Roadblock Deir Dibwan 7093 º¹ Ramallah/Al Bireh Burqa 2372 P Under / Overpass 'Ein Yabrud N/A ## Jericho ### Constructed Barrier Jerusalem Total Population: 12590 ## Projected Barrier Bethlehem ## Deir as Sudan Deir as Sudan ## Under Construction ## Hebron Prohibited Roads C /" An Nabi Salih Partially Prohibited ¬Ç ## 15 Umm Safa/" Restricted Use ## # # Comparing situations Pre-Intifada Totally Prohibited and August 2005 Localities 65 Year 2000 <all other values> August 2005 Atara ## D ¬Çº¹P Palestinian localities Natural center º¹P Access routes Road used today 11 12 ##º¹P/" Road prior to Intifada 'Ein'Ein YabrudYabrud 12 /" /" 10 At Tayba /" 9 Beitin Ç Travel Time (min) DCO 2 D ¬ /"Ç## /" ¬/"3 ## 1 Closed village cluster Ramallahº¹P 1 42 /" 43 Deir Dibwan /" /" º¹P the part of the the of part the Burqa Ramallah delimitation the concerning D ¬Ç Beituniya /" ## º¹DP Closure mapping is a work in Qalandiya QalandiyaCamp progress. Closure data is Ç collected by OCHA field staff º¹ ¬ Beit Duqqu and is subject to change. P Atarot 144 Maps will be updated regularly. ### ¬Ç Cartography: OCHA Humanitarian 170 Al Judeira Information Centre - October 2005 Al Jib Beit 'Anan ## Bir Nabala Base data: Al 036Jib 12 O C H A O C H OCHA updateBeit AugustIjza 2005 losedFor comments village contact <[email protected]> cluster # # Tel. -

10Th Anniversary Israel, Chicago

From the Office of For Release: May 12, 1958 Senator Hubert H. Humphrey Monday a.m. 140 Senate Office Building Washington 25, D. c. CApitol 4-3121, Ext. 2424 REGIONAL MIDE.A.sr.r . I OPEN SKIES I INSPEC,TlON PEOPOSED AS I PILOT I DISARMAMENT PROJEC'l' An 'open skies' a ~ial and ground inspection system in the Middle East was urged by Senator Hubert H. Humphrey (D-Minn.) in Chicago last night as "a pilot project· of inestimable value for the cause of world disarmament. " Addressing the Independence Festival in. Chicago Stadium celebrating Israel's lOth Anniversary, Senator Humphrey, chairman of. both the Disarmament and Middle East Subcommittees in the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, called attention to Prime Minister Ben-Gurion '·s support for a regional dis- armament pact in the Middle East and declared that an adequate inspection system in that area "could allay apprehension over the possibility of a sur- prise attack by one state upon another." "All of the countries of the Middle East should seriously consider this proposal," Senator Humphrey declared. "The United States should take the initiative in calling.' it 1.1P for discus sion before the United Nations. "The people of the Middle East, who have already themselves shown their aspirations for peace by accepting new forms of peacekeeping machinery such as the United Nations Emer gency Force, could make another significant contribution to world peace if they would be the first to adopt, in their own region, the principle of inspection against surprise attack. "That many of the Middle Eastern governments favor this principle was demonstrated in 1955 ~en they supported a United Nations resolution on the open skies plan, and again a week or two ago when they continued their support of the concept in the Artie debate in the United Nations. -

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Open Jerusalem Edited by Vincent Lemire (Paris-Est Marne-la-Vallée University) and Angelos Dalachanis (French School at Athens) VOLUME 1 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/opje Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City Edited by Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire LEIDEN | BOSTON Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing CC-BY-NC-ND License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. The Open Jerusalem project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) (starting grant No 337895) Note for the cover image: Photograph of two women making Palestinian point lace seated outdoors on a balcony, with the Old City of Jerusalem in the background. American Colony School of Handicrafts, Jerusalem, Palestine, ca. 1930. G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/mamcol.054/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Dalachanis, Angelos, editor. -

Deir Dibwan Town Profile

Deir Dibwan Town Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation 2012 Palestinian Localities Study Ramallah Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, village committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 1 Palestinian Localities Study Ramallah Governorate Background This report is part of a series of booklets, which contain compiled information about each city, town, and village in the Ramallah Governorate. These booklets came as a result of a comprehensive study of all localities in Ramallah Governorate, which aims at depicting the overall living conditions in the governorate and presenting developmental plans to assist in developing the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment;" the project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID). The "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment" was designed to study, investigate, analyze and document the socio-economic conditions and the needed programs and activities to mitigate the impact of the current unsecure political, economic and social conditions in Ramallah Governorate. The project's objectives are to survey, analyze, and document the available natural, human, socioeconomic and environmental resources, and the existing limitations and needs assessment for the development of the rural and marginalized areas in Ramallah Governorate. -

Pursuing the Zionist Dream on the Palestinian Frontier: a Critical Approach to Herzl’S Altneuland

61 ACTA NEOPHILOLOGICA UDK: 323.13(=411.16) DOI: 10.4312/an.53.1-2.61-81 Pursuing the Zionist Dream on the Palestinian Frontier: A Critical Approach to Herzl’s Altneuland Saddik Mohamed Gohar Abstract This paper critically examines Theodore Herzl’s canonical Zionist novel, Altneuland /Old New Land as a frontier narrative which depicts the process of Jewish immigration to Pal- estine as an inevitable historical process aiming to rescue European Jews from persecution and establish a multi-national Utopia on the land of Palestine. Unlike radical Zionist narratives which underlie the necessity of founding a purely Jewish state in the holy land, Altneuland depicts an egalitarian and cosmopolitan community shared by Jews, Arabs and other races. The paper emphasizes that Herzl’s Zionist project in Altneuland is not an extension of western colonialism par excellence. Herzl’s narrative is a pragmatic appropri- ation of frontier literature depicting Palestine as a new frontier and promoting a construct of mythology about enthusiastic individuals who thrived in the desert while serving the needs of an enterprising and progressive society. Unlike western colonial narratives which necessitate the elimination of the colonized natives, Herzl’s novel assimilates the indige- nous population in the emerging frontier community. Keywords: Zionism, Frontier, Immigration, Palestine, Narrative, History, Jews, Colonization Acta_Neophilologica_2020_FINAL.indd 61 23. 11. 2020 07:19:49 62 SADDIK MOHAMED GOHAR INTRODUCTION The story of the Zionist immigration to Palestine continues to live; Zionist lit- erature reflects and recreates this experience in a heroic mode, re-enacting again and again the first moments of the colonization and settlement of the Palestinian landscape. -

AUGUST 6, 1976 ~ PER COPY 16 PAGES up to a Year in Jail May Be Im- Tive to Jan

J , R.I. J EW IS H HISTORICAL ASS OC . 13 0 SESSIOC'lS ST . PROVIDE NCE , RI 0 2 906 Senate Provision Curbs Boycotting Or Bribery WASHINGTON: Under a provi $100 million in 1977. sion approved by the Senate recent The antiboycett language would ly. American concerns that boycott affect transactions made 30 days or Israel or use bribery as a foreign more after the provisions become sales tool arc in line to lose millions law. The anti-bribe section would of dollars in tax benefits. generally become effective retroac I V()LUME LIX, NUMBER 23 FRIDAY, AUGUST 6, 1976 ~ PER COPY 16 PAGES Up to a year in jail may be im- tive to Jan. I. ---------------------------------;::;;;;;;;;;;----- posed upon any business executives In approving the package of who fail to report corporate income amendments dealing with foreign -j derived as a result of a bribe. or income, the Senate killed one of earnings in any country that dozens of provisions that have been requires participation in a boycott. attacked as favoring special The provision was added to a interests. multibillion dollar tax bill. Still sub Tnists Abroad ject to House consideration, the In writing the tax bill, the provision is much tougher than Finance Committee accepted a recommended by the Ford Ad House-approved section that ministration. tooghened tax treatment of trusts The anti-boycott and anti-bribery set up in foreign countries by provisions were tacked on to a Americans to benefit their children . package that affects tax treatment The House language would have of income earned by Americans or applied the stricter rules as of May US businesses abroad. -

The Banking System in Israel

CHAPTER XIV THE BANKING SYSTEM IN ISRAEL I. DEVELOPMENT OF THE BANKING SYSTEM Israel possesses a welldeveloped banking system, evidenced by the fact that bank deposits constitute some 60 per cent of the money supply. Apart from one or two banks founded in the period of the Ottoman Empire (such as, for example, the Bank Leumi LeTsrael B.M., formerly the AngloPalestine Bank Ltd.), most of the banks now functioning in Israel were established during the British Mandate. During this period, some dozens of banks were founded; but the economic crises which hit Palestine during the Abyssinian War and again at the outbreak of World War II, resulted in the liquidation of many of the smaller, and the strengthening of the more solid, institutions. The Banking Ordinance, 1921, which ifxed the legal basis of bank operations, was amended several times and the changes were eventually consolidated in the Banking Ordinance, 1941, which is still in force today. The Ordinance provided, inter alia, that no banking business might be conducted without a permit from the High Commissioner, that the minimum approved nominal capital of a bank be £P. 50,000, the minimum paidup capital be £P.25,000; and that all banks submit a monthly report to the Financial Secretary on their assets and liabilities. The Ordin ance also imposed on all banks the obligation to publish an annual balance sheet and a profit and loss account. The High Commissioner appointed a Controller of Banks and an Advisory Committee for Banking. With the creation of the State of Israel, the powers exercised by the High Commissioner under the Banking Ordinance were transferred to the Minister of Finance, and the control over banking activities was vested in the Department of Bank Control, a partofthe Ministryof Finance A new Advisory Committee for Bank ing was appointed by the Minister of Finance; its function was to consider problems relating to the activities of the banking system and to submit its recommendations to the Minister. -

Weekly Report on Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory ( 05-11 June 2014) Thursday, 12 June 2014 00:00

Weekly Report On Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory ( 05-11 June 2014) Thursday, 12 June 2014 00:00 Tulkarm- Israeli forces destroy a house belonging to a Palestinian family in Far’one village. Reuters Israeli forces continue systematic attacks against Palestinian civilians and property in the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) In a new extra-judicial execution, Israeli forces killed a member of an armed group and wounded 3 civilians, including a child, in the Gaza Strip A Palestinian civilian died as he was previously wounded by the Israeli forces in the northwest of Beit Lahia in the northern Gaza Strip. Israeli forces continued to use excessive force against peaceful protesters in the West Bank. 3 Palestinian demonstrators were wounded in the demonstrations of Ni’lin and Bil’in, west of Ramallah. 5 Palestinian civilians, including a child, were wounded in a demonstration organized in solidarity with the Palestinian administrative detainees on hunger strike. Israeli forces conducted 76 incursions into Palestinian communities in the West Bank. 28 Palestinian civilians, including 4 children and woman, were arrested. A Palestinian civilian was wounded when Israeli forces moved into al-‘Arroub refugee camp, north of Hebron. Israel has continued its efforts to create a Jewish majority in occupied East Jerusalem Israeli forces raided the Pal Media office and arrested two of its workers and a guest of “Good Morning Jerusalem” program. Israel continued to impose a total closure on the oPt and has isolated the Gaza Strip from the outside world. Israeli forces established dozens of checkpoints in the West Bank. -

Domestically Owned Versus Foreign-Owned Banks in Israel

Domestic bank intermediation: domestically owned versus foreign-owned banks in Israel David Marzuk1 1. The Israeli banking system – an overview A. The structure of the banking system and its scope of activity Israel has a highly developed banking system. At the end of June 2009, there were 23 banking corporations registered in Israel, including 14 commercial banks, two mortgage banks, two joint-service companies and five foreign banks. Despite the spate of financial deregulation in recent years, the Israeli banking sector still plays a key role in the country’s financial system and overall economy. It is also highly concentrated – the five main banking groups (Bank Hapoalim, Bank Leumi, First International Bank, Israel Discount Bank and Mizrahi-Tefahot Bank) together accounted for 94.3% of total assets as of June 2009. The two largest groups (Bank Leumi and Bank Hapoalim) accounted for almost 56.8% of total assets. The sector as a whole and the large banking groups in particular are organised around the concept of “universal” banking, in which commercial banks offer a full range of retail and corporate banking services. Those services include: mortgages, leasing and other forms of finance; brokerage in the local and foreign capital markets; underwriting and investment banking; and numerous specialised services. Furthermore, until the mid-1990s, the banking groups were deeply involved in non-financial activities. However, a law passed in 1996 forced the banks to divest their controlling stakes in non-financial companies and conglomerates (including insurance companies). This development was part of a privatisation process which was almost completed in 2005 (with the important exception of Bank Leumi).