INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: August 6th, 2007 I, __________________Julia K. Baker,__________ _____ hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Philosophy in: German Studies It is entitled: The Return of the Child Exile: Re-enactment of Childhood Trauma in Jewish Life-Writing and Documentary Film This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Dr. Katharina Gerstenberger Dr. Sara Friedrichsmeyer Dr. Todd Herzog The Return of the Child Exile: Re-enactment of Childhood Trauma in Jewish Life-Writing and Documentary Film A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) In the Department of German Studies Of the College of Arts and Sciences 2007 by Julia K. Baker M.A., Bowling Green State University, 2000 M.A., Karl Franzens University, Graz, Austria, 1998 Committee Chair: Katharina Gerstenberger ABSTRACT “The Return of the Child Exile: Re-enactment of Childhood Trauma in Jewish Life- Writing and Documentary Film” is a study of the literary responses of writers who were Jewish children in hiding and exile during World War II and of documentary films on the topic of refugee children and children in exile. The goal of this dissertation is to investigate the relationships between trauma, memory, fantasy and narrative in a close reading/viewing of different forms of Jewish life-writing and documentary film by means of a scientifically informed approach to childhood trauma. Chapter 1 discusses the reception of Binjamin Wilkomirski’s Fragments (1994), which was hailed as a paradigmatic traumatic narrative written by a child survivor before it was discovered to be a fictional text based on the author’s invented Jewish life-story. -

French and German Cultural Cooperation, 1925-1954 Elana

The Cultivation of Friendship: French and German Cultural Cooperation, 1925-1954 Elana Passman A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: Dr. Donald M. Reid Dr. Christopher R. Browning Dr. Konrad H. Jarausch Dr. Alice Kaplan Dr. Lloyd Kramer Dr. Jay M. Smith ©2008 Elana Passman ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT ELANA PASSMAN The Cultivation of Friendship: French and German Cultural Cooperation, 1925-1954 (under the direction of Donald M. Reid) Through a series of case studies of French-German friendship societies, this dissertation investigates the ways in which activists in France and Germany battled the dominant strains of nationalism to overcome their traditional antagonism. It asks how the Germans and the French recast their relationship as “hereditary enemies” to enable them to become partners at the heart of today’s Europe. Looking to the transformative power of civic activism, it examines how journalists, intellectuals, students, industrialists, and priests developed associations and lobbying groups to reconfigure the French-German dynamic through cultural exchanges, bilingual or binational journals, conferences, lectures, exhibits, and charitable ventures. As a study of transnational cultural relations, this dissertation focuses on individual mediators along with the networks and institutions they developed; it also explores the history of the idea of cooperation. Attempts at rapprochement in the interwar period proved remarkably resilient in the face of the prevalent nationalist spirit. While failing to override hostilities and sustain peace, the campaign for cooperation adopted a new face in the misguided shape of collaborationism during the Second World War. -

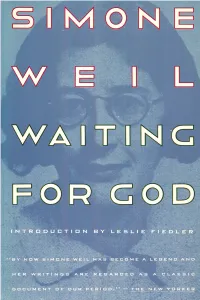

Waiting for God by Simone Weil

WAITING FOR GOD Simone '111eil WAITING FOR GOD TRANSLATED BY EMMA CRAUFURD rwith an 1ntroduction by Leslie .A. 1iedler PERENNIAL LIBilAilY LIJ Harper & Row, Publishers, New York Grand Rapids, Philadelphia, St. Louis, San Francisco London, Singapore, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto This book was originally published by G. P. Putnam's Sons and is here reprinted by arrangement. WAITING FOR GOD Copyright © 1951 by G. P. Putnam's Sons. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written per mission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address G. P. Putnam's Sons, 200 Madison Avenue, New York, N.Y.10016. First HARPER COLOPHON edition published in 1973 INTERNATIONAL STANDARD BOOK NUMBER: 0-06-{)90295-7 96 RRD H 40 39 38 37 36 35 34 33 32 31 Contents BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Vll INTRODUCTION BY LESLIE A. FIEDLER 3 LETTERS LETTER I HESITATIONS CONCERNING BAPTISM 43 LETTER II SAME SUBJECT 52 LETTER III ABOUT HER DEPARTURE s8 LETTER IV SPIRITUAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY 61 LETTER v HER INTELLECTUAL VOCATION 84 LETTER VI LAST THOUGHTS 88 ESSAYS REFLECTIONS ON THE RIGHT USE OF SCHOOL STUDIES WITII A VIEW TO THE LOVE OF GOD 105 THE LOVE OF GOD AND AFFLICTION 117 FORMS OF THE IMPLICIT LOVE OF GOD 1 37 THE LOVE OF OUR NEIGHBOR 1 39 LOVE OF THE ORDER OF THE WORLD 158 THE LOVE OF RELIGIOUS PRACTICES 181 FRIENDSHIP 200 IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT LOVE 208 CONCERNING THE OUR FATHER 216 v Biographical 7\lote• SIMONE WEIL was born in Paris on February 3, 1909. -

CHRONOLOGIE Herbert Harrer

CHRONOLOGIE Herbert Harrer 1836 Am lZ Februar sucht Simon Georg Sina 1845 Am 15. Januar wird der Bau der Streckenach 1855 Am 12. Februarwird der Kauf der Linie 1873 Am 4. Mai werden die neuenTrassen Freiherr von Hodos um eine Konzession Brucka.d. Leitha neuerlich aufgenommen. Wien - Bruck a.d. Leitha genehmigt, die der Verbindungsbahn Richtung Haupt fOreine Bahn Wien - Raab an. Der Bahn 1845 Der Raaber Bahnhof(an der Stelle des Obernahme durch die StEG erfolgt am zollamt (heute Wien Mitte) durch den hof ist beim "Canalhafen" (des Wiener spateren Ostbahnhofes) wird weitgehend 1.Oktober 1855. Arsenal- und den Steudeltunnel mit Neustiidter Kanals, heute BahnhofWien fertiggestellt. 1856 Simon Georg Sina Freiherrvon Hodos Aufnahme des Personenverkehrs Mitte) geplant. 1846 Am 31. Juliwird die StreckeWien - Bruck stirbt am 18. MaL er6ffnet. 1837 Am 1. Marz akzeptiert Sina geanderte Be a.d. Leithaeingleisig fertiggestellt. Die 1857 Am 1.August fiihrt der erste Schnellzug 1873 Der Frachtenbahnhof der StEG (AufschGt dingungen der Regierung - damit ist der Eroffnung des Bahnhofs und der Strecke von Wien nach Ljubljana (Laibach). tung bis 5 Meter) wird mit 15Gleisen Standort des spatersn SOd- und Ostbahn verzogertsich wegen Hochwassers 1857 Am 15. Oktober wird die Verbindungsbahn gebaut. hofes fixiert. bis 12. September. zum Hauptzollamt (heute Wien Mitte) mit 1873 Am 15. Mai wird die Strecke Favoriten 1838 Sina erhalt am 2. Januareine vcrlauflge 1848 Von 9.Oktober bis 15. Novemberist der der Trasse Gberden Ghegaplatz und durch Frachtenbahnhof der StEG - als erste Baugenehmigung. Verkehrauf der BruckerLiniewegen der den SchweizerGarten eroffnet. direkte Verbindung zwischen SOd- und 1838 20. Marz, GrOndung der Wien-Raaber Revolution eingestellt. -

Apalast Schlafen Haben Was Verf

Zeitschri des Max-Planck-Instituts für europäische Rechtsgeschichte Rechts R geschichte g Rechtsgeschichte www.rg.mpg.de http://www.rg-rechtsgeschichte.de/rg2 Rg 2 2003 231 – 234 Zitiervorschlag: Rechtsgeschichte Rg 2 (2003) http://dx.doi.org/10.12946/rg02/231-234 Iring Fetscher Deckname Z. Dieser Beitrag steht unter einer Creative Commons cc-by-nc-nd 3.0 231 Deckname Z. * Das »Office for Strategic Studies« (OSS) hochrangigen Kriegsgefangenen und Kommu- wurde erst 1942, ein Jahr nach Kriegseintritt nisten bestehenden »Nationalkomitees Freies der USA geschaffen, es war ein Vorläufer des Deutschland« in den USA unter deutschen Emig- CIA. Seine Aufgaben bestanden nicht allein in ranten und in der Öffentlichkeit gemacht hatte. der Beschaffung von Informationen über den Bemühungen, ein ähnlich glaubwürdig demo- Zustand der feindlichen Streitkräfte in Europa kratisches Manifest zustande zu bringen, schei- und Asien, sondern unter anderem auch in der terten schließlich daran, dass Thomas Mann sich Entwicklung von Möglichkeiten und Vorstel- im letzten Augenblick der Mitarbeit entzog. lungen für die – nach erfolgreicher Beendigung Erika Mann veröffentlichte zur gleichen Zeit der Kämpfe – einsetzende Aufbauarbeit in den einen Artikel in der Exilzeitung »Aufbau«, in zu besetzenden Ländern. Dieser Aufgabe diente dem sie den samt und sonders nazistisch ge- auch die Beauftragung Carl Zuckmayers mit wordenen Deutschen so gut wie alles Recht auf einem informativen Bericht über die politische eine ersprießliche Zukunft absprach. Auf diesen und moralische Zuverlässigkeit, oder wenigstens Artikel antwortete Zuckmayer in einem »offe- »Brauchbarkeit« von Angehörigen der künstle- nen Brief« im gleichen Blatt und verteidigte die rischen Elite, soweit sie im Deutschen Reich Notwendigkeit, zwischen verantwortlichen und geblieben war; brauchbar nämlich für Betei- schuldigen Nazis auf der einen Seite und anderen ligung am kulturellen Leben in einem neuen, Deutschen zu unterscheiden. -

Measurement System Evaluation for Upwind/Downwind Sampling of Fugitive Dust Emissions

Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 11: 331–350, 2011 Copyright © Taiwan Association for Aerosol Research ISSN: 1680-8584 print / 2071-1409 online doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2011.03.0028 Measurement System Evaluation for Upwind/Downwind Sampling of Fugitive Dust Emissions John G. Watson1,2*, Judith C. Chow1,2, Li Chen1, Xiaoliang Wang1, Thomas M. Merrifield3, Philip M. Fine4, Ken Barker5 1 Desert Research Institute, 2215 Raggio Parkway, Reno, NV, USA 89512 2 Institute of Earth Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 10 Fenghui South Road, Xi’an High-Tech Zone, Xi’an, China 710075 3 BGI Incorporated, 58 Guinan Street, Waltham, MA, USA, 02451 4 South Coast Air Quality Management District, 21865 Copley Drive, Diamond Bar, CA, USA 91765 5 Sully-Miller Contracting Co., 135 S. State College Boulevard, Brea, CA, USA 92821 ABSTRACT Eight different PM10 samplers with various size-selective inlets and sample flow rates were evaluated for upwind/ downwind assessment of fugitive dust emissions from two sand and gravel operations in southern California during September through October 2008. Continuous data were acquired at one-minute intervals for 24 hours each day. Integrated filters were acquired at five-hour intervals between 1100 and 1600 PDT on each day because winds were most consistent during this period. High-volume (hivol) size-selective inlet (SSI) PM10 Federal Reference Method (FRM) filter samplers were comparable to each other during side-by-side sampling, even under high dust loading conditions. Based on linear regression slope, the BGI low-volume (lovol) PQ200 FRM measured ~18% lower PM10 levels than a nearby hivol SSI in the source-dominated environment, even though tests in ambient environments show they are equivalent. -

The Formation of the Communist Party of Germany and the Collapse of the German Democratic Republi C

Enclosure #2 THE NATIONAL COUNCI L FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEA N RESEARC H 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, N .W . Washington, D.C . 20036 THE NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARC H TITLE : Politics Unhinged : The Formation of the Communist Party of Germany and the Collapse of the German Democratic Republi c AUTHOR : Eric D . Weitz Associate Professo r Department of History St . Olaf Colleg e 1520 St . Olaf Avenu e Northfield, Minnesota 5505 7 CONTRACTOR : St . Olaf College PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR : Eric D . Weit z COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 806-3 1 DATE : April 12, 199 3 The work leading to this report was supported by funds provided by the National Council for Soviet and East Europea n Research. The analysis and interpretations contained in the report are those of the author. i Abbreviations and Glossary AIZ Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung (KPD illustrated weekly newspaper ) Alter Verband Mineworkers Union Antifas Antifascist Committee s BL Bezirksleitung (district leadership of KPD ) BLW Betriebsarchiv der Leuna-Werke BzG Beiträge zur Geschichte der Arbeiterbewegung Comintern Communist International CPSU Communist Party of the Soviet Unio n DMV Deutscher Metallarbeiter Verband (German Metalworkers Union ) ECCI Executive Committee of the Communist Internationa l GDR German Democratic Republic GW Rosa Luxemburg, Gesammelte Werke HIA, NSDAP Hoover Institution Archives, NSDAP Hauptarchi v HStAD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf IGA, ZPA Institut für Geschichte der Arbeiterbewegung, Zentrales Parteiarchi v (KPD/SED Central Party Archive -

Guest Information English

English Guest information dfgdfgd Location and how to get here Bus The city is well-connected and situated in the tri-city Central bus station (ZOB), Bahnhofstraße, area Bremen, Hanover and Hamburg; the well-develo- station forecourt ped infrastructure allows a comfortable arrival from City bus all directions. Allerbus, Verden-Walsroder Eisenbahn (VWE), Tel. (0)4231 92270, www.allerbus.de, www.vwe-verden.de VBN-PLUS shared taxi Tel. (0)4231 68 888 Regional bus Hamburg Verkehrsverbund Bremen/Niedersachsen (VBN), A27 Tel. (0)421 596059, www.vbn.de A29 Taxi A28 Bremen A1 Taxi Böschen Tel. (0)4231 66160 or 69001 Taxi Kahrs Tel. (0)4231 82906 A7 Taxi Köhler Tel. (0)4231 5500 Taxi Sieling Tel. (0)4231 930000 Verden A27 Car parks The city of Verden has a car park routing system taking Weser Aller A1 you safely and comfortably into the city centre. Car park P 1, multi-storey car parks P 3 and ‘Nordertor‘ are recommended if you want to visit the shopping street Hannover and the historic old town. Caravan park Conrad-Wode-Straße 15 spaces up to a length of max. 12 m GPS coordinates: E = 9° 13‘ 42“ N = 52° 55‘ 32“ Marina of the Verden motor boat club International telephone code for Germany: 0049 Höltenwerder 2 Connections Car rental Motorway A27 (Hanover-Bremen) Hertz Federal road B215 (Rotenburg/Wümme-Minden) Marie-Curie-Straße 4, Tel. (0)4231 965015 Airports Access to the attractions and sights of the city Bremen 40 km Before you reach the city centre, the tourist information Hanover 80 km system and the parking information system will direct Hamburg 125 km you to the attractions, sights, hotels and car parks. -

German (GERM) 1

German (GERM) 1 GERM 2650. Business German. (4 Credits) GERMAN (GERM) Development of oral proficiency used in daily communication within the business world, preparing the students both in technical vocabulary and GERM 0010. German for Study Abroad. (2 Credits) situational usage. Introduction to specialized vocabulary in business and This course prepares students for studying abroad in a German-speaking economics. Readings in management, operations, marketing, advertising, country with no or little prior knowledge of German. It combines learning banking, etc. Practice in writing business correspondence. Four-credit the basics of German with learning more about Germany, and its courses that meet for 150 minutes per week require three additional subtleties and specifics when it comes to culture. It is designed for hours of class preparation per week on the part of the student in lieu of undergraduate and graduate students, professionals and language an additional hour of formal instruction. learners at large, and will introduce the very basics of German grammar, Attribute: IPE. vocabulary, and everyday topics (how to open up a bank account, register Prerequisite: GERM 2001. for classes, how to navigate the Meldepflicht, or simply order food). It GERM 2800. German Short Stories. (4 Credits) aims to help you get ready for working or studying abroad, and better This course follows the development of the short story as a genre in communicate with German-speaking colleagues, family and friends. German literature with particular emphasis on its manifestation as a GERM 1001. Introduction to German I. (5 Credits) means of personal and social integration from the middle of the 20th An introductory course that focuses on the four skills: speaking, reading, century to the present day. -

Nr. 49 „Erweiterung Campingpark Südheide“

Gemeinde Winsen (Aller) OT Winsen – Landkreis Celle Bebauungsplan Winsen (Aller) Nr. 49 „Erweiterung Campingpark Südheide“ Begründung Verf.-Stand: §§ 3(1) + 4(1) BauGB §§ 3(2) + 4(2) BauGB § 10 BauGB Begründung: 16.12.2010 31.03.2011 27.09.2011 Plan: 13.10.2010 31.03.2011 27.09.2011 Dr.-Ing. S. Strohmeier Dipl.-Geogr. K. Schröder-Effinghausen Dipl.-Ing. B.-O. Bennedsen Gemeinde Winsen (Aller) – OT Winsen – Bebauungsplan Nr. 49 „Erweiterung Campingpark Südheide“ INHALT TEIL 1: ZIELE, GRUNDLAGEN UND INHALTE DES BEBAUUNGSPLANES...................1 1 Erfordernis der Planänderung: Allgemeine Ziele und Zwecke..........................................................1 2 Räumlicher Geltungsbereich.............................................................................................................1 3 Bestand.............................................................................................................................................2 3.1 Erschließung...........................................................................................................................2 3.2 Flächennutzung und Flächenausbildung ................................................................................2 4 Planungsvorgaben ............................................................................................................................2 4.1 Überörtliche Planungen ..........................................................................................................2 4.1.1 Raumordnung und Landesplanung ...........................................................................2 -

The Kafka Protagonist As Knight Errant and Scapegoat

tJBIa7I vAl, O7/ THE KAFKA PROTAGONIST AS KNIGHT ERRANT AND SCAPEGOAT THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Mary R. Scrogin, B. A. Denton, Texas August, 1975 10 Scrogin, Mary R., The Kafka Protagonist as night Errant and Scapegoat. Master of Arts (English), August, 1975, 136 pp., bibliography, 34 titles. This study presents an alternative approach to the novels of Franz Kafka through demonstrating that the Kafkan protagonist may be conceptualized in terms of mythic arche- types: the knight errant and the pharmakos. These complementary yet contending personalities animate the Kafkan victim-hero and account for his paradoxical nature. The widely varying fates of Karl Rossmann, Joseph K., and K. are foreshadowed and partially explained by their simultaneous kinship and uniqueness. The Kafka protagonist, like the hero of quest- romance, is engaged in a quest which symbolizes man's yearning to transcend sterile human existence. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION . .......... 1 II. THE SPARED SACRIFICE...-.-.................... 16 III. THE FAILED QUEST... .......... 49 IV. THE REDEMPTIVE QUEST........... .......... 91 BIBLIOGRAPHY.. --...........-.......-.-.-.-.-....... 134 iii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Speaking of the allegorical nature of much contemporary American fiction, Raymond Olderman states in Beyond the Waste Land that it "primarily reinforces the sense that contemporary fact is fabulous and may easily refer to meanings but never to any one simple Meaning." 1 A paraphrase of Olderman's comment may be appropriately applied to the writing of Franz Kafka: a Kafkan fable may easily refer to meanings but never to any one Meaning. -

Die Deutsche Jugendbewegung

Deinz S. Rosenbusch Die deutsche Jugendbewegung in ihren pädagogischen Formen und Wirkungen dipa-Verlag Frankfurt am Main INHALT Seite Vorbemerkung 7 Abkürzungen 9 Einleitung 11 Erstes Kapitel 15 Die Phasen der deutschen Jugendbewegung I. Die gesellschaftliche Situation für die Entstehung der 15 Jugendbewegung 11. Die Schule als besonderer Kritikpunkt 19 III. Ludwig Gurlitts Bedeutung für die frühe Jugendbewegung 22 IV. Der geschichtliche Ablauf der Jugendbewegung 24 V. Topologische Darstellung der Jugendbewegung 37 VI. Das Verhältnis zur Schule 39 VII. Das Verhältnis der Jugendbewegung zu Parteien 44 VIII. Das Menschenbild der Jugendbewegung 50 Zweites Kapitel 63 Praxis und Prinzipien jugendbewegter Erziehung I. Erziehung als tertiäre, partikularistische Kategorie in der 63 vital-regressiven Phase 11. Hans Breuers Vorstellungen von der Erziehung zum Wandervogel- 67 deutschen III. Das Prinzip der Sel~sterziehung in der introversiv-reflektorischen 69 Phase 1. Die Erziehungsvorstellungen der studentischen Verbände 69 a) Die Akademischen Freischaren 69 b) Die Akademischen Vereinigungen 71 2_ Die Erziehungsvorstellungen des Wandervogels 72 3. Die DefInition der Selbsterziehung durch Bruno Lemke 73 4. P'adagogische Betrachtung der Meißnerformel 75 IV. Erziehung als gesellschaftliche Aufgabe in der utopisch-progressiven 76 Phase 1. Die Erfahrungen mit der Selbsterziehung im Krieg 76 2. Erziehung als gesellschaftlich defmiertes Engagement 78 3. Erziehungspolitische Forderungen der Jenaer Tagung - Erziehung 80 als Instrument der Revolution v. Der pädagogische Aktivismus der resignativ-sektiererischen Phase 83 VI. Die Gemeinschaft in ihrer Erziehungsfunktion ' 84 Drittes Kapitel 91 Das Führerturn als wichtige erzieherische Konponente der Jugendbewegung I. Vorbemerkungen 91 ll. Funktionsdifferenzierung der Führerrollen 92 llI. Führertypen der vital-regressiven Phase und die Bedeutung von 93 Führern flir die Entwicklung der Jugendbewegung überhaupt IV.