Virginian Writers Fugitive Verse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origins of a Free Press in Prerevolutionary Virginia: Creating

Dedication To my late father, Curtis Gordon Mellen, who taught me that who we are is not decided by the advantages or tragedies that are thrown our way, but rather by how we deal with them. Table of Contents Foreword by David Waldstreicher....................................................................................i Acknowledgements .........................................................................................................iii Chapter 1 Prologue: Culture of Deference ...................................................................................1 Chapter 2 Print Culture in the Early Chesapeake Region...........................................................13 A Limited Print Culture.........................................................................................14 Print Culture Broadens ...........................................................................................28 Chapter 3 Chesapeake Newspapers and Expanding Civic Discourse, 1728-1764.......................57 Early Newspaper Form...........................................................................................58 Changes: Discourse Increases and Broadens ..............................................................76 Chapter 4 The Colonial Chesapeake Almanac: Revolutionary “Agent of Change” ...................97 The “Almanacks”.....................................................................................................99 Chapter 5 Women, Print, and Discourse .................................................................................133 -

A-1 Layout 1

Deer Hunt S UBSCRIBE ONLINE AT Kids: Free Ticket ‘Til March 2 THEHERALDADVOCATE.COM To State Fair . Column 12A . Story 10A The Herald-Advocate Hardee County’s Hometown Coverage 114th Year, No. 10 3 Sections, 32 Pages 70¢ Plus 5¢ Sales Tax Thursday, February 6, 2014 Boyfriend Charged In Baby’s Murder By CYNTHIA KRAHL Wauchula, has been charged Attorney’s Office, jury members permanent disability or perma- Rivera, 22, the baby’s mother, A Hardee County Grand Jury with first-degree murder and ag- agreed there was sufficient nent disfigurement.” are currently being held in the has handed up a murder indict- gravated child abuse in the Nov. cause to charge Jaimes with cap- It further accused Jaimes of Hardee County Jail on other, but ment against the boyfriend of a 5 death of 15-month-old Joel ital-felony murder and first-de- causing such “trauma to the similar, charges. Both had been woman whose baby was pro- Jordan Chavez. gree-felony abuse. head and body” of the baby be- arrested on Nov. 6 on a felony nounced dead by an Emergency Grand jurors delivered the in- Their indictment alleges that tween Nov. 4 and Nov. 5 to count of child neglect after Room doctor. dictment on Friday. between Oct. 1 and Nov. 5, cause his death “from a premed- officers investigating Joel’s Hector Tavera Jaimes, 24, of After hearing testimony and Jaimes abused Joel to the point itated design.” death allegedly disco- 310 W. Townsend St., evidence presented by the State of causing “great bodily harm, Jaimes and Kaycha Lynn See MURDER 2A Brant BRAVE BEAUTIES Jaimes Avoids Man, 81, Prison Accused Of By CYNTHIA KRAHL Of The Herald-Advocate A former city commissioner and funeral director has avoided Attempted prison and been sentenced to a lengthy probation following charges he defrauded a number of clients. -

Waiting for God by Simone Weil

WAITING FOR GOD Simone '111eil WAITING FOR GOD TRANSLATED BY EMMA CRAUFURD rwith an 1ntroduction by Leslie .A. 1iedler PERENNIAL LIBilAilY LIJ Harper & Row, Publishers, New York Grand Rapids, Philadelphia, St. Louis, San Francisco London, Singapore, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto This book was originally published by G. P. Putnam's Sons and is here reprinted by arrangement. WAITING FOR GOD Copyright © 1951 by G. P. Putnam's Sons. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written per mission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address G. P. Putnam's Sons, 200 Madison Avenue, New York, N.Y.10016. First HARPER COLOPHON edition published in 1973 INTERNATIONAL STANDARD BOOK NUMBER: 0-06-{)90295-7 96 RRD H 40 39 38 37 36 35 34 33 32 31 Contents BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Vll INTRODUCTION BY LESLIE A. FIEDLER 3 LETTERS LETTER I HESITATIONS CONCERNING BAPTISM 43 LETTER II SAME SUBJECT 52 LETTER III ABOUT HER DEPARTURE s8 LETTER IV SPIRITUAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY 61 LETTER v HER INTELLECTUAL VOCATION 84 LETTER VI LAST THOUGHTS 88 ESSAYS REFLECTIONS ON THE RIGHT USE OF SCHOOL STUDIES WITII A VIEW TO THE LOVE OF GOD 105 THE LOVE OF GOD AND AFFLICTION 117 FORMS OF THE IMPLICIT LOVE OF GOD 1 37 THE LOVE OF OUR NEIGHBOR 1 39 LOVE OF THE ORDER OF THE WORLD 158 THE LOVE OF RELIGIOUS PRACTICES 181 FRIENDSHIP 200 IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT LOVE 208 CONCERNING THE OUR FATHER 216 v Biographical 7\lote• SIMONE WEIL was born in Paris on February 3, 1909. -

Powers of the Earth Vs. Godby Father Rick Bolte

May 2012 Powers of the Earth vs. God by Father Rick Bolte “Power corrupts; absolute power corrupts absolutely.” vision of God coming in power as we know it is that these That adage proves itself over and over again throughout predictions began in the Old Testament and applied as history. Even when good people and institutions gain much to Jesus’ first coming as to his second. One of the access to power, corruption comes in. We’ve seen this in reason the Jews missed Jesus as the long awaited Messiah our Catholic Church particularly with the Inquisition and was that his manifestations of power did not fit the earthly the corrupt popes of the Middle Ages. expressions they expected. This could happen to us as well. The Companion Defined in Webster’s, power is “a possession of control, Jesus’ expression of power is vastly different than the is the newsletter of authority, or influence over others.” We normally think of power the world recognizes. 1 John 4:8 tells us that “God St. Timothy Parish power as the ability to get things done regardless of the is love”. Jesus’ power was the power of love. This is not a P.O. Box 120 obstacles that may get in the way. Power comes from power the world gives must attention to. This is not a Union, KY 41091-0120 859.384.1100 leadership roles where we have the influence, authority, power that can force anyone to do anything. This doesn’t and the right connections to make things happen. Power seem to have any power over evil. -

Music and the American Civil War

“LIBERTY’S GREAT AUXILIARY”: MUSIC AND THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR by CHRISTIAN MCWHIRTER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2009 Copyright Christian McWhirter 2009 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Music was almost omnipresent during the American Civil War. Soldiers, civilians, and slaves listened to and performed popular songs almost constantly. The heightened political and emotional climate of the war created a need for Americans to express themselves in a variety of ways, and music was one of the best. It did not require a high level of literacy and it could be performed in groups to ensure that the ideas embedded in each song immediately reached a large audience. Previous studies of Civil War music have focused on the music itself. Historians and musicologists have examined the types of songs published during the war and considered how they reflected the popular mood of northerners and southerners. This study utilizes the letters, diaries, memoirs, and newspapers of the 1860s to delve deeper and determine what roles music played in Civil War America. This study begins by examining the explosion of professional and amateur music that accompanied the onset of the Civil War. Of the songs produced by this explosion, the most popular and resonant were those that addressed the political causes of the war and were adopted as the rallying cries of northerners and southerners. All classes of Americans used songs in a variety of ways, and this study specifically examines the role of music on the home-front, in the armies, and among African Americans. -

Measurement System Evaluation for Upwind/Downwind Sampling of Fugitive Dust Emissions

Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 11: 331–350, 2011 Copyright © Taiwan Association for Aerosol Research ISSN: 1680-8584 print / 2071-1409 online doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2011.03.0028 Measurement System Evaluation for Upwind/Downwind Sampling of Fugitive Dust Emissions John G. Watson1,2*, Judith C. Chow1,2, Li Chen1, Xiaoliang Wang1, Thomas M. Merrifield3, Philip M. Fine4, Ken Barker5 1 Desert Research Institute, 2215 Raggio Parkway, Reno, NV, USA 89512 2 Institute of Earth Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 10 Fenghui South Road, Xi’an High-Tech Zone, Xi’an, China 710075 3 BGI Incorporated, 58 Guinan Street, Waltham, MA, USA, 02451 4 South Coast Air Quality Management District, 21865 Copley Drive, Diamond Bar, CA, USA 91765 5 Sully-Miller Contracting Co., 135 S. State College Boulevard, Brea, CA, USA 92821 ABSTRACT Eight different PM10 samplers with various size-selective inlets and sample flow rates were evaluated for upwind/ downwind assessment of fugitive dust emissions from two sand and gravel operations in southern California during September through October 2008. Continuous data were acquired at one-minute intervals for 24 hours each day. Integrated filters were acquired at five-hour intervals between 1100 and 1600 PDT on each day because winds were most consistent during this period. High-volume (hivol) size-selective inlet (SSI) PM10 Federal Reference Method (FRM) filter samplers were comparable to each other during side-by-side sampling, even under high dust loading conditions. Based on linear regression slope, the BGI low-volume (lovol) PQ200 FRM measured ~18% lower PM10 levels than a nearby hivol SSI in the source-dominated environment, even though tests in ambient environments show they are equivalent. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT of INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION in Re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMEN

USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 1 of 354 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION ) Case No. 3:05-MD-527 RLM In re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE ) (MDL 1700) SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMENT ) PRACTICES LITIGATION ) ) ) THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO: ) ) Carlene Craig, et. al. v. FedEx Case No. 3:05-cv-530 RLM ) Ground Package Systems, Inc., ) ) PROPOSED FINAL APPROVAL ORDER This matter came before the Court for hearing on March 11, 2019, to consider final approval of the proposed ERISA Class Action Settlement reached by and between Plaintiffs Leo Rittenhouse, Jeff Bramlage, Lawrence Liable, Kent Whistler, Mike Moore, Keith Berry, Matthew Cook, Heidi Law, Sylvia O’Brien, Neal Bergkamp, and Dominic Lupo1 (collectively, “the Named Plaintiffs”), on behalf of themselves and the Certified Class, and Defendant FedEx Ground Package System, Inc. (“FXG”) (collectively, “the Parties”), the terms of which Settlement are set forth in the Class Action Settlement Agreement (the “Settlement Agreement”) attached as Exhibit A to the Joint Declaration of Co-Lead Counsel in support of Preliminary Approval of the Kansas Class Action 1 Carlene Craig withdrew as a Named Plaintiff on November 29, 2006. See MDL Doc. No. 409. Named Plaintiffs Ronald Perry and Alan Pacheco are not movants for final approval and filed an objection [MDL Doc. Nos. 3251/3261]. USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 2 of 354 Settlement [MDL Doc. No. 3154-1]. Also before the Court is ERISA Plaintiffs’ Unopposed Motion for Attorney’s Fees and for Payment of Service Awards to the Named Plaintiffs, filed with the Court on October 19, 2018 [MDL Doc. -

APRIL 1995 R!' a ! DY April 1995 Number 936

APRIL 1995 R!' A ! DY April 1995 Number 936 I Earthquake epicen.,.s -IN THE SEA ?ABOVE THE SEA 4 The wave 22Weather prediction 6 What's going on? 24What is El Nino? 8 Knowledge is power 26Clouds, typhoons and hurricanes 10 Bioluminescence 28Highs, lows and fronts 11 Sounds in the sea 29Acid rain 12 Why is the ocean blue? 30 Waves 14 The sea floor 31The Gulf Stream 16 Going with the floe 32 The big picture: blue and littoral waters 18 Tides *THE ENVIRONMENT 34 TheKey West Campaign 19 Navyoceanographers 36 What's cookin' on USS Theodore Roosevek c 20Sea lanes of communication 38 GW Sailors put the squeeze on trash 40 Cleaning up on the West Coast 42Whale flies south after rescue 2 CHARTHOUSE M BEARINGS 48 SHIPMATES On the Covers Front cover: View of the Western Pacific takenfrom Apollo 13, in 1970. Photo courtesy of NASA. Opposite page: "Destroyer Man,"oil painting by Walter Brightwell. Back cover: EM3 Jose L. Tapia aboard USS Gary (FFG 51). Photo by JO1 Ron Schafer. so ” “I Charthouse Drug Education For Youth program seeks sponsors The Navy is looking for interested active and reserve commandsto sponsor the Drug Education For Youth (DEFY) program this summer. In 1994, 28 military sites across the nation helped more than 1,500 youths using the prepackaged innovative drug demand reduction program. DEFY reinforces self-esteem, goal- setting, decision-making and sub- stance abuse resistance skills of nine to 12-year-old children. This is a fully- funded pilot program of theNavy and DOD. DEFY combines a five to eight- day, skill-building summer camp aboard a military base with a year-long mentor program. -

Paleoseismology of the North Anatolian Fault at Güzelköy

Paleoseismology of the North Anatolian Fault at Güzelköy (Ganos segment, Turkey): Size and recurrence time of earthquake ruptures west of the Sea of Marmara Mustapha Meghraoui, M. Ersen Aksoy, H Serdar Akyüz, Matthieu Ferry, Aynur Dikbaş, Erhan Altunel To cite this version: Mustapha Meghraoui, M. Ersen Aksoy, H Serdar Akyüz, Matthieu Ferry, Aynur Dikbaş, et al.. Pale- oseismology of the North Anatolian Fault at Güzelköy (Ganos segment, Turkey): Size and recurrence time of earthquake ruptures west of the Sea of Marmara. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, AGU and the Geochemical Society, 2012, 10.1029/2011GC003960. hal-01264190 HAL Id: hal-01264190 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01264190 Submitted on 1 Feb 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Article Volume 13, Number 4 12 April 2012 Q04005, doi:10.1029/2011GC003960 ISSN: 1525-2027 Paleoseismology of the North Anatolian Fault at Güzelköy (Ganos segment, Turkey): Size and recurrence time of earthquake ruptures west of the Sea of Marmara Mustapha Meghraoui Institut de Physique du Globe de Strasbourg (UMR 7516), F-67084 Strasbourg, France ([email protected]) M. Ersen Aksoy Institut de Physique du Globe de Strasbourg (UMR 7516), F-67084 Strasbourg, France Eurasia Institute of Earth Sciences, Istanbul Technical University, 34469 Istanbul, Turkey Now at Instituto Dom Luiz, Universidade de Lisboa, P-1750-129 Lisbon, Portugal H. -

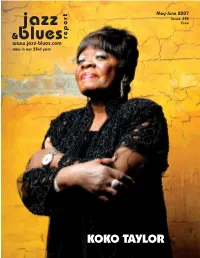

May-June 293-WEB

May-June 2007 Issue 293 jazz Free &blues report www.jazz-blues.com now in our 33rd year KOKO TAYLOR KOKO TAYLOR Old School Published by Martin Wahl A New CD... Communications On Tour... Editor & Founder Bill Wahl & Appearing at the Chicago Blues Festival Layout & Design Bill Wahl The last time I saw Koko Taylor Operations Jim Martin she was a member of the audience at Pilar Martin Buddy Guy’s Legends in Chicago. It’s Contributors been about 15 years now, and while I Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, no longer remember who was on Kelly Ferjutz, Dewey Forward, stage that night – I will never forget Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, Koko sitting at a table surrounded by Peanuts, Wanda Simpson, Mark fans standing about hoping to get an Smith, Dave Sunde, Duane Verh, autograph...or at least say hello. The Emily Wahl and Ron Weinstock. Queen of the Blues was in the house that night...and there was absolutely Check out our costantly updated no question as to who it was, or where website. Now you can search for CD Reviews by artists, titles, record she was sitting. Having seen her elec- labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 trifying live performances several years of reviews are up and we’ll be times, combined with her many fine going all the way back to 1974. Alligator releases, it was easy to un- derstand why she was engulfed by so Koko at the 2006 Pocono Blues Festival. Address all Correspondence to.... many devotees. Still trying, but I still Jazz & Blues Report Photo by Ron Weinstock. -

AMERICAN MANHOOD in the CIVIL WAR ERA a Dissertation Submitted

UNMADE: AMERICAN MANHOOD IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Michael E. DeGruccio _________________________________ Gail Bederman, Director Graduate Program in History Notre Dame, Indiana July 2007 UNMADE: AMERICAN MANHOOD IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA Abstract by Michael E. DeGruccio This dissertation is ultimately a story about men trying to tell stories about themselves. The central character driving the narrative is a relatively obscure officer, George W. Cole, who gained modest fame in central New York for leading a regiment of black soldiers under the controversial General Benjamin Butler, and, later, for killing his attorney after returning home from the war. By weaving Cole into overlapping micro-narratives about violence between white officers and black troops, hidden war injuries, the personal struggles of fellow officers, the unbounded ambition of his highest commander, Benjamin Butler, and the melancholy life of his wife Mary Barto Cole, this dissertation fleshes out the essence of the emergent myth of self-made manhood and its relationship to the war era. It also provides connective tissue between the top-down war histories of generals and epic battles and the many social histories about the “common soldier” that have been written consciously to push the historiography away from military brass and Lincoln’s administration. Throughout this dissertation, mediating figures like Cole and those who surrounded him—all of lesser ranks like major, colonel, sergeant, or captain—hem together what has previously seemed like the disconnected experiences of the Union military leaders, and lowly privates in the field, especially African American troops. -

Separating Fact from Fiction in the Aiolian Migration

hesperia yy (2008) SEPARATING FACT Pages399-430 FROM FICTION IN THE AIOLIAN MIGRATION ABSTRACT Iron Age settlementsin the northeastAegean are usuallyattributed to Aioliancolonists who journeyed across the Aegean from mainland Greece. This articlereviews the literary accounts of the migration and presentsthe relevantarchaeological evidence, with a focuson newmaterial from Troy. No onearea played a dominantrole in colonizing Aiolis, nor is sucha widespread colonizationsupported by the archaeologicalrecord. But the aggressive promotionof migrationaccounts after the PersianWars provedmutually beneficialto bothsides of theAegean and justified the composition of the Delian League. Scholarlyassessments of habitation in thenortheast Aegean during the EarlyIron Age are remarkably consistent: most settlements are attributed toAiolian colonists who had journeyed across the Aegean from Thessaly, Boiotia,Akhaia, or a combinationof all three.1There is no uniformityin theancient sources that deal with the migration, although Orestes and his descendantsare named as theleaders in mostaccounts, and are credited withfounding colonies over a broadgeographic area, including Lesbos, Tenedos,the western and southerncoasts of theTroad, and theregion betweenthe bays of Adramyttion and Smyrna(Fig. 1). In otherwords, mainlandGreece has repeatedly been viewed as theagent responsible for 1. TroyIV, pp. 147-148,248-249; appendixgradually developed into a Mountjoy,Holt Parker,Gabe Pizzorno, Berard1959; Cook 1962,pp. 25-29; magisterialstudy that is includedhere Allison Sterrett,John Wallrodt, Mal- 1973,pp. 360-363;Vanschoonwinkel as a companionarticle (Parker 2008). colm Wiener, and the anonymous 1991,pp. 405-421; Tenger 1999, It is our hope that readersinterested in reviewersfor Hesperia. Most of trie pp. 121-126;Boardman 1999, pp. 23- the Aiolian migrationwill read both articlewas writtenin the Burnham 33; Fisher2000, pp.