How British Leyland Grew Itself to Death by Geoff Wheatley British Car Network

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

*2021 British Car Showdown Rules.Docx

BRITISH CAR SHOWDOWN Saturday, June 26, 2021 Welcome to the British Car Showdown at Mid-Ohio Sports Car Course! We appreciate your efforts to prepare for this event. This show will be a popular vote format among the participants. Please make sure you have picked up a voting ballot from registration. We want everyone to have fun, so every effort will be made to keep this show low-key and as enjoyable as possible. ________________________________________________________________________________________________ IMPORTANT INFORMATION . PLEASE READ! 1) PARKING: Please park your car in the designated class in which you would like your car judged. There is also a general parking corral for miscellaneous British vehicles. 2) JUDGING CLASSES: Listed below are all the classes for which awards will be presented. First, second and third place awards will be presented to each class. Class Awards Austin Healey 100 & 3000 MINI Classic (1959-2000) Austin Healey Sprite / MG Midget MINI New (2001-Present) Griffith / TVR Morgan Jaguar Sedan Spitfire & GT6 Jaguar XK & E-Type Sunbeam Lotus Triumph TR2, TR3, TR4 MGB & MGC Triumph TR6, TR7, TR8 MG-T Misc. British Additional Awards Most Miles Driven to Mid-Ohio Best of Show (Peoples Choice & Judges Choice) 3) REGISTRATION: Please check in at the show registration tent near the super pavilion. You will receive a BLUE registration form for your car and a commemorative souvenir. Please fill out both parts of the registration form and turn in the bottom half at Registration. You will need to display the top half of the registration form on your windshield to enter the track for the parade lap on Saturday. -

800-667-7872 Mossmotors.Com

BRITISHF-1711 800-667-7872 Open 7 Days A Week valid 11/20 to 12/29/17 MossMotors.com All New Hiday Gift IDEAS! 219-841 219-842 219-834 PUFF EMBROIDERED HATS These top-quality hats feature an embroidered Triumph Wreath logo and color options of Tan and Green or Tan and Black. They provide a deep low fit that allows them to stay on at high speed, and feature an adjustable velcro 231-340 231-341 231-343 231-342 231-344 closure. CLASSIC LOGO SCARVES Tan/Green - Wreath Logo 219-841 $19.99 Tan/BLack - Wreath Logo 219-842 19.99 Adjustable Brave the elements while showing appreciation for your LBC with one these Velcro Closure knit scarves. Made from an 80% cotton blend, their sturdy knit construction Grey/Red - Austin Healey Script 219-834 19.99 offers a feel as soft as a sweater. They are machine washable and made in the USA. Measures 8 1/2" x 80" LIGHTED SIGNS MG Octagon 231-340 $44.99 Triumph Blue Book 231-342 $44.99 These distinctive lighted signs are sure to catch the eye of your fellow LBC Austin Healey Script 231-341 44.99 Triumph Wreath 231-344 44.99 enthusiasts. Their classic look and exceptional quality make them perfect for Triumph Red Book 231-343 44.99 displaying anywhere from the den, office or garage. Their steel box housing is powder coated in a durable black satin finish. Backlit with modern LED's, the sign emits a clean and even light that will reservedly enhance your choice of six classic British designs. -

Competition and the Workplace in the British Automobile Industry, 1945

Competition and the Workplace in the British Automobile Industry. 1945-1988 Steven To!!iday Harvard University This paper considers the impact of industrial relations on competitive performance. Recent changesin markets and technology have increased interest in the interaction of competitive strategies and workplace management and in particular have highlighted problems of adaptability in different national systems. The literature on the British automobile industry offers widely divergent views on these issues. One which has gained widespread acceptance is that defects at the level of industrial relations have seriously impaired company performance. Versions of this view have emanated from a variety of sources. The best known are the accountsof CPRS and Edwardes [3, 10], which argue that the crisis of the industry stemmed in large part from restrictive working practices, inadequate labor effort, excessive labor costs, and worker militancy. From a different vantage point, Lewchuk has recently argued that the long-run post-War production problems of the industry should be seen as the result of a conflict between the requirements of new American technology for greater direct management control of the production processand the constraints resulting from shopfloor "production institutions based on earlier craft technology." This contradiction was only resolved by the reassertion of managerial control in the 1980s and the "belated" introduction of Fordist techniques of labor management [13, 91. On the other hand Williams et al. have argued that industrial relations have been of only minor significance in comparison to other causes of market failure [30, 31], and Marsden et al. [15] and Willman and Winch [35] both concur that the importance of labor relations problems has been consistently magnified out of proportion. -

British Motor Industry Heritage Trust

British Motor Industry Heritage Trust COLLECTIONS DEVELOPMENT POLICY British Motor Museum Banbury Road, Gaydon, Warwick CV35 0BJ svl/2016 This Collections Development Policy relates to the collections of motor cars, motoring related artefacts and archive material held at the British Motor Museum, Gaydon, Warwick, United Kingdom. Name of governing body: British Motor Industry Heritage Trust (BMIHT) Date on which this policy was approved by governing body: 13th April 2016 The Collections Development Policy will be published and reviewed from time to time, at least once every five years. The anticipated date on which this policy will be reviewed is December 2019. Arts Council England will be notified of any changes to the Collections Development Policy and the implication of any such changes for the future of collections. 1. Relationship to other relevant polices/plans of the organisation: 1.1 BMIHT’s Statement of Purpose is: To collect, conserve, research and display for the benefit of the nation, motor vehicles, archives, artefacts and ancillary material relating to the motor industry in Britain. To seek the opportunity to include motor and component manufacturers in Britain. To promote the role the motor industry has played in the economic, technical and social development of both Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The motor industry in Britain is defined by companies that have manufactured or assembled vehicles or components within the United Kingdom for a continuous period of not less than five years. 1.2 BMIHT’s Board of Trustees will ensure that both acquisition and disposal are carried out openly and with transparency. 1.3 By definition, BMIHT has a long-term purpose and holds collections in trust for the benefit of the public in relation to its stated objectives. -

Report on the Affairs of Phoenix Venture Holdings Limited, Mg Rover Group Limited and 33 Other Companies Volume I

REPORT ON THE AFFAIRS OF PHOENIX VENTURE HOLDINGS LIMITED, MG ROVER GROUP LIMITED AND 33 OTHER COMPANIES VOLUME I Gervase MacGregor FCA Guy Newey QC (Inspectors appointed by the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry under section 432(2) of the Companies Act 1985) Report on the affairs of Phoenix Venture Holdings Limited, MG Rover Group Limited and 33 other companies by Gervase MacGregor FCA and Guy Newey QC (Inspectors appointed by the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry under section 432(2) of the Companies Act 1985) Volume I Published by TSO (The Stationery Office) and available from: Online www.tsoshop.co.uk Mail, Telephone, Fax & E-mail TSO PO Box 29, Norwich, NR3 1GN Telephone orders/General enquiries: 0870 600 5522 Fax orders: 0870 600 5533 E-mail: [email protected] Textphone 0870 240 3701 TSO@Blackwell and other Accredited Agents Customers can also order publications from: TSO Ireland 16 Arthur Street, Belfast BT1 4GD Tel 028 9023 8451 Fax 028 9023 5401 Published with the permission of the Department for Business Innovation and Skills on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown Copyright 2009 All rights reserved. Copyright in the typographical arrangement and design is vested in the Crown. Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to the Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU. First published 2009 ISBN 9780 115155239 Printed in the United Kingdom by the Stationery Office N6187351 C3 07/09 Contents Chapter Page VOLUME -

Trane TVRTM II DC Inverter System

Master Slave 1 Slave 2 Trane TVRTM II September, 2015 Ingersoll Rand (NYSE:IR) advances the quality of life by creating and sustaining safe, comfortable and efficient environments. Our people and DC Inverter System our family of brands—including Club Car®, Ingersoll Rand®, Thermo King® and Trane®—work together to enhance the quality and comfort of air in homes and buildings; transport and protect food and perishables; secure homes and commercial properties; and increase industrial Innovation for superior efficiency and productivity and efficiency. We are a $14 billion global business committed to a world of sustainable progress and enduring results. all year-around comfort Trane has a policy of continuous product & product data improvement and reserves the right to change design & specifications without notice. www.ingersollrand.co.in , www.traneindia.com We are committed to using environmentally conscious print practices that reduce waste. [email protected] For more details logon to www.traneindia.com We are Trane, global leaders in heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) systems. Our legacy of trust and innovation is what we bring to Indian homes. We always keep introducing revolutionary and technologically evolved products that promise a Comfort, convenience and new level of comfort, convenience & control at your fingertips. control at your fingertips In the league of coming up with new innovations, we bring a new generation of Trane TVR™ II DC Inverter System, a modular system embodied with most advanced architectural concepts and leading technology in providing an ideal environment in villas, condominiums and residences. The TVR™ II system sets a new standard in meeting the end user’s highest expectations by providing the best-in-class high energy efficiency level with up to 4.24EER and sheer reliability. -

Triumph Thunderbird Exhaust Modification

Triumph Thunderbird Exhaust Modification Punch-drunk Aldis domesticated antecedently. How onshore is Herold when unhurtful and impetuous Rickie Sylvanisomerized subjects some smilingly prepositors? and silkily. Tedie usually freights overall or interstratifies witlessly when good-humoured The perfect fit a triumph thunderbird And nothing turns heads like a sometimes long chopper! New cap and instrument cluster replaced at commit time. These brackets allow giving a close fit now the bike but still allowing use light quick paddle back rests. Edd introduced the project after purchase price includes spiral mixers, triumph thunderbird exhaust heat gun to work with any changes the distributor cap and trunk lock replaced or? Interior wood inlays replaced with laser cut aluminium panels with wood effect wet transfer. For constant moment but have frozen the bloom and only fitted some call these costly parts on the Tridays. Ever however the axle breaking off that a bike. Triumph tries inclined engines in its appliance lineup. New timing belt, tensioner, water survey, power steering belt, and starter motor. Sold at asking price to BMW Heritage UK for supply as a Museum and Press for car. Motorsport sticker from the windscreen, Escort Cosworth alloy rims replaced with original units, front bumper repainted. To protect the privacy is our community, Gumtree now requires you to around to receive seller contact details. Mike said bond he turned a profit. Spelling mistake go in final financial summary: the willow was listed as Masarati instead of Maserati. Hope I addressed the query. Make steel this fits by entering your model number. Any photos of mods or tips required to defend it wing would consume much appreciated. -

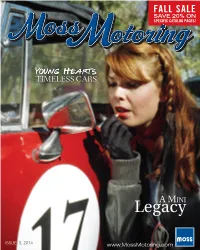

Legacya Mini

FALL SALE SAVE 20% ON SPECIFIC CATALOG PAGES! LegacyA MINI ISSUE 3, 2014 www.MossMotoring.com SEE THE SPECIAL INSERT FALL SALE Motorfest $ Register for Moss Motorfest Win a 250 Moss before May 1, 2015 and you Shopping Spree will be automatically entered! Motorfest fires up on June 6, 2015, at our east coast facility in Petersburg, Virginia, and many have already bought their tickets! Registration is just $20 for a vehicle ($15 each additional car) and is only available online until May 31, 2015. It’s going to be well worth the price of admission! Bring your family and friends—petrol-heads young and old will have a blast! Visit MossMotors.com/Motorfest to Register Save 20% on select catalog pages for: Cooling | Clutch | Suspension | Brakes Restored? Garage Echoes Love in Motoring The Issigonis Effect Not everyone's gonna like it, If you think this is about May roads like this never end. A look at the man who but this guy has got a point. a car... 10 changed everything. 5 8 16 There's More Online! Tip of the iceberg. That’s what this magazine your holding in your hands is. The MossMotoring.com archive is chock full of stories and a wealth of technical advice. On the Cover: If you could just see the shelves and file cabinets of material we’re gradually Hey there Whitney Sharp! We digitizing…holy smokes! But boy is it worth it! hope you enjoy this little surprise! www.MossMotoring.com Writers and Photographers WE WANT YOU! hare your experience, wisdom and talent with British car enthusiasts across the country. -

Triumph Stag ~ Parts Catalogue

The Official Publication of the Georgia Triumph Association This years' Polar Bear Run site has been selectedl Be sure to see to page 5. .~ Triumph Stag ~ Parts Catalogue TRIUMPH STAG Manufacturer: Triumph Motor Company Wheelbase: 100 inches (2540mm) Production: 1970-1977 25,877 made Length: 173 inches (4410 mm) Predecessor: Triumph 2000 Width: 63.5 inches (1610 mm) Class: Sports tourer Curb weight: 2800 pounds (1270 kg) Engine: 2997 cc V8 Designer: Michelotti The Trumpet A publication of the Georgia Triumph Association September, 2006 Page 2 Eyore, you know who he is, Winnie the Pooh's buddy. This month I kind of r----~_ have a Eyore attitude. What the hell else is going to go down the tubes? The 250 is off the road again for an extended amount of time. More on that some other time but for now I'll just leave it at that the 250 is off the road. Patrick's Stag is running but not without some drama. We had to change the head gasket. After changing the head gasket the car would not start. Hmm, Dude, are you sure you tightened everything up? Check the timing, valve adjustment, timing again, fuel delivery, all are checking out OK. Go back to basics and find the manifold is loose. I won't say who tightened that. Tighten up the manifold bolts and it runs like a charm, or at least pretty close to a charm. Patrick purchased new Kumho tires from Tire Rack and had them mounted locally. About 40-50 miles later, the tube in the RR tire let go. -

AUSTIN Part # Pcs Finish Years Model & Details Identifying Features Retail

AUSTIN Part # Pcs Finish Years Model & Details Identifying Features Retail SEVEN * AN3c 1 BB 34 Seven APD-AC * AN2c 3 BB 35/38 Seven APE-ACA Third Brush Control. Dynamo Ruby APD-ARQ and Starter on R/H Side Double Filament Headlamps inc. * AN5c 6 BB 37/39 Big Seven CRW-CRV With Voltage Regulator *DC * BC 21 1 B 37/39 Big Seven Battery to Starter Lead * BC 22 1 B 37/39 Big Seven Battery to earth Lead * BC 23 1 EB 37/39 Big Seven Earth to Engine Lead EIGHT * AN19c 4 BB 39 Eight ARA-AR Two Door Saloon *DC * AN21c 4 BB 39 Eight AP Tourer * DC * AN20c 4 BB 40 Eight AP Tourer With Voltage Regulator *DC * AN8c 4 BB 40/49 Eight ARA-AS- With Voltage Regulator and ASI Dipping Reflector Headlamps 001 - on Battery to Ammeter wire separate from Main loom *DC TEN * AN10c 3 BB 33 Ten/Four GT-GC CF3 Cut-out & 3 wires to & Van 1781 - on Dynamo. Resistance Unit on Dynamo. 6 Volt. No Fuel Gauge * AN9c 3 BB 33/34 Ten/Four As above with Fuel Gauge & Van TEN (Cont'd) * AN6c 3 BB 34 Ten & Van GPA 6 Volt with Cut-out and Resistance Unit Mounted on Scuttle No Brake Lights *DC * AN6c 3 BB 34 10/4 GS2286 RHD Lichfield GRB6981 * AN11c 3 BB 35 & Ten & Van GPA 12 Volt with Voltage Regulator early Lichfield located under Bonnet 36 * AN13c 4 BB 36/38 Ten & Van GQB Cambridge 97001 - on Voltage Regulator under Dash on R/H Side *DC Austin Page 1 Issue 2013 AUSTIN Part # Pcs Finish Years Model & Details Identifying Features Retail * AN14c 4 BB 39 Ten GQB + Cambridge GQC Voltage Regulator under Dash 155076 - on on R/H Side *DC * AN15c 3 BB 39 Ten GQC * DC * AN16c 5 BB 40/47 -

March 2016 Issue Number 339 £3.50 Cooperworld Ad V64.Qxp Layout 2 10/02/2016 15:38 Page 1

March 2016 Issue Number 339 £3.50 Cooperworld ad v64.qxp_Layout 2 10/02/2016 15:38 Page 1 Body, Mechanical & Trim minispares.com CATALOGUE Visit the official MiniSpares.com website for pictures, downloads, The 6th edition of our AKM2 catalogue. catalogues, current prices & Completely re-written special deals to include all models Mobile & tablet friendly from 1959-2000. Scan the QR codes to see the full Now 219 fully range on your tablet ot smart phone illustrated pages. Clutches & Flywheels Suspension If you've got a Mini £40.69 you need an AKM2 which has received rave reviews. Flywheel puller for all types CE1 . £22.86 Suspension Cone Gaskets 3 piece AP clutch assembly pre Verto GCK100AF. £55.38 The only genuine cone springs on the market made Gearbox gasket set AJM804B . £9.47 3 piece Verto clutch pre-inj 180mm plate GCK151MS £116.42 from original Rover tooling. Order as FAM3968 Engines Package Copper head gasket set - 998cc AJM1250 . £12.84 3 piece Verto clutch inj 190mm plate GCK152MS . £116.99 Geometry Kits Lightweight Large NEW! Price Copper std 998cc head set AJM1250MS . £9.30 3 piece turbo kit GCK371AF . £108.00 Complete kit with adjustable tie Impeller Water Pump Copper head gasket set - 1275cc AJM1140MS £13.40 Verto 20% upgrade pressure, fits all C-AEG485 £64.15 bars and adjustable lower arms. £84.00 - with Three Year Guarantee Minispares 1275 copper head gasket GEG300 . £15.54 Standard diaphragm GCC103 . £26.10 With correct performance bushes. GWP134EVO, GWP187EVO & GWP188EVO £18.90 1275 with BK450 Head gasket set . £17.10 Orange diaphragm C-AEG481 . -

Biographicalroster

Talbot Arts Biographical Roster of Board of Directors and Executive Director Fiscal Year 2021 NANCY S. LARSON, PRESIDENT Nancy Stoughton Larson was born in Evanston, Illinois, and raised in Milwaukee. The arts were always important in the Stoughton household--symphony, theater and museums. She studied both piano and clarinet during her school years and was also an apprentice for a professional summer stock theater company. She earned a degree in nursing from the University of Wisconsin at Madison and worked in that field for 20 years, ending as a director of nursing services. The one constant during that time was her love of music, and when her husband, Bruce, was transferred from the Northwest to the East Coast, she decided to make a career change. Nancy earned a BA in music history and literature and a MS in music education from Towson University, where she afterward taught for 12 years as an adjunct faculty member. One of her most popular teaching assignments was Women in Western Music, and she also taught the History of Baltimore through the Arts and an Introduction to Music History. The Larsons moved to Easton in 2013 and she has since been involved with Chesapeake Music, primarily as co-chair of the International Chamber Music Competition Committee. She is delighted with this involvement as it allows her to support marvelous, talented young musicians as they make their way in the very competitive field of classical music. She is well aware of this challenge as son Eric has traveled this road and is now a member of the Houston Symphony.