Competition and the Workplace in the British Automobile Industry, 1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Motor Industry Heritage Trust

British Motor Industry Heritage Trust COLLECTIONS DEVELOPMENT POLICY British Motor Museum Banbury Road, Gaydon, Warwick CV35 0BJ svl/2016 This Collections Development Policy relates to the collections of motor cars, motoring related artefacts and archive material held at the British Motor Museum, Gaydon, Warwick, United Kingdom. Name of governing body: British Motor Industry Heritage Trust (BMIHT) Date on which this policy was approved by governing body: 13th April 2016 The Collections Development Policy will be published and reviewed from time to time, at least once every five years. The anticipated date on which this policy will be reviewed is December 2019. Arts Council England will be notified of any changes to the Collections Development Policy and the implication of any such changes for the future of collections. 1. Relationship to other relevant polices/plans of the organisation: 1.1 BMIHT’s Statement of Purpose is: To collect, conserve, research and display for the benefit of the nation, motor vehicles, archives, artefacts and ancillary material relating to the motor industry in Britain. To seek the opportunity to include motor and component manufacturers in Britain. To promote the role the motor industry has played in the economic, technical and social development of both Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The motor industry in Britain is defined by companies that have manufactured or assembled vehicles or components within the United Kingdom for a continuous period of not less than five years. 1.2 BMIHT’s Board of Trustees will ensure that both acquisition and disposal are carried out openly and with transparency. 1.3 By definition, BMIHT has a long-term purpose and holds collections in trust for the benefit of the public in relation to its stated objectives. -

Report on the Affairs of Phoenix Venture Holdings Limited, Mg Rover Group Limited and 33 Other Companies Volume I

REPORT ON THE AFFAIRS OF PHOENIX VENTURE HOLDINGS LIMITED, MG ROVER GROUP LIMITED AND 33 OTHER COMPANIES VOLUME I Gervase MacGregor FCA Guy Newey QC (Inspectors appointed by the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry under section 432(2) of the Companies Act 1985) Report on the affairs of Phoenix Venture Holdings Limited, MG Rover Group Limited and 33 other companies by Gervase MacGregor FCA and Guy Newey QC (Inspectors appointed by the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry under section 432(2) of the Companies Act 1985) Volume I Published by TSO (The Stationery Office) and available from: Online www.tsoshop.co.uk Mail, Telephone, Fax & E-mail TSO PO Box 29, Norwich, NR3 1GN Telephone orders/General enquiries: 0870 600 5522 Fax orders: 0870 600 5533 E-mail: [email protected] Textphone 0870 240 3701 TSO@Blackwell and other Accredited Agents Customers can also order publications from: TSO Ireland 16 Arthur Street, Belfast BT1 4GD Tel 028 9023 8451 Fax 028 9023 5401 Published with the permission of the Department for Business Innovation and Skills on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown Copyright 2009 All rights reserved. Copyright in the typographical arrangement and design is vested in the Crown. Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to the Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU. First published 2009 ISBN 9780 115155239 Printed in the United Kingdom by the Stationery Office N6187351 C3 07/09 Contents Chapter Page VOLUME -

How British Leyland Grew Itself to Death by Geoff Wheatley British Car Network

How British Leyland Grew Itself To Death By Geoff Wheatley British Car Network I have always wondered how a British motor company that made trucks and other commercial vehicles, ever got its hands on Jaguar, Triumph, and of course MG. Furthermore, how this successful commercial company managed to lose the goodwill and loyal customers of these popular vehicles. The story starts some fifteen years before British Leyland became part of the domestic vehicle market in the UK, and of course overseas, especially for Jaguar, a top international brand name in the post war years. In the early 1950s the idea of Group Industries was the flavor of the month. Any company worth its salt was ready to join forces with a willing competitor, or several competitors to form a “Commercial Group”. In consequence we had the Textile Groups, International Banking Groups, The British Nylon Group, Shell and BP Group etc. The theory was simple, by forming production groups producing similar products and exchanging both marketing and production techniques, costs would be reduced and sales would increase. The British Government, who had an investment in the British Motor Industry to help the growth of exports to earn needed US Dollars, was very much in favor of the Group Policy being applied to the major production companies in the UK including the Nuffield Organization and Austin Corporation. Smaller companies like Jaguar who were also successful exporters were encouraged to take the same view on production and sales, however they did not jump on the “Group” bandwagon and remained independent for a few more years. -

Universal Joints

GKN Driveline Rösrath GKN Driveline Stockholm GKN Service International GmbH GKN Driveline Service Scandinavia AB Nußbaumweg 19-21 P.O. Box 3100, Stensätravägen 9 Universal Joints D-51503 Rösrath SE-127 03 Skärholmen Fon: ++ 49 - 22 05 - 806- 0 Fon: ++ 46 8 6039700 Edition 2005 / 2006 Fax: ++ 49 - 22 05 - 806 - 204 Fax: ++ 46 8 6039701 GKN Driveline Barcelona GKN Driveline Carrières Pol. Ind Can Salvatella GKN Glenco SAS Avda. Arrahona, 54 170 rue Léonard de Vinci E-08210 Barberá del Vallés (Barcelona) F-78955 Carrières sous Poissy Almacén/Warehouse: Fon: ++ 33 1 30 06 84 00 Fon: ++ 34 93 718 40 15 Fax: ++ 33 1 30 06 84 01 Fax: ++ 34 93 729 54 14 Oficina/Office: Fon: ++ 34 93 718 64 85 GKN Driveline Minworth Fax: ++ 34 93 729 47 59 GKN Driveline Service Limited Unit 5, Kingsbury Business Park Kingsbury Road GKN Driveline Amsterdam Minworth GKN Service Benelux B.V. Birmingham Haarlemmerstraatweg 155-159 GB-B76 9DL NL-1165 MK Halfweg Fon: ++ 44 121 313 1661 Nederland Fax: ++ 44 121 313 2074 Fon: ++ 31-20-40 70 207 Fax: ++ 31-20-40 70 227 GKN Driveline Leek GKN Driveline Service Limited GKN Driveline Brussel Higher Woodcroft GKN Service Benelux B.V. Leek 410, rue Emile Pathéstraat Staffordshire B-1190 Brussel - Bruxelles GB-ST13 5QF Fon: ++ 32-2 334 9880 Fon: ++ 44 1538 384278 Fax: ++ 32-2 334 9892 Fax: ++ 44 1538 371265 ervices 07/2005 S GKN Driveline Milano GKN Driveline Wien Uni-Cardan Italia S.p.A. GKN Service Austria GmbH Via G. Ferraris, 125 Slamastraße 32 I-20021 Ospiate di Bollate (MI) Postfach 36A Fon: ++ 39 02 38338.1 A-1230 Wien Fax: ++ 39 02 33301030 Fon: ++ 43 1 616 38 80 Fax: ++ 43 1 616 38 28 Copyright: GKN Industrial & Distribution GB General Information 1. -

Alan and Richard Jensen Produced Their First Car in 1928 When They

Alan and Richard Jensen produced their first car in 1928 when they converted a five year old Austin 7 Chummy Saloon into a very stylish two seater with cycle guards, louvred bonnet and boat-tail. This was soon sold and replaced with another Austin 7. Then came a car produced on a Standard chassis followed by a series of specials based on the Wolseley Hornet, a popular sporting small car of the time. The early 1930s saw the brothers becoming joint managing directors of commercial coachbuilders W J Smith & Sons and within three years the name of the company was changed to Jensen Motors Limited. Soon bodywork conversions followed on readily available chassis from Morris, Singer, Standard and Wolseley. Jensen’s work did not go unnoticed as they received a commission from actor Clark Gable to produced a car on a US Ford V8 chassis. This stylish car led to an arrangement with Edsel Ford for the production of a range of sports cars using a Jensen designed chassis and powered by Ford V8 engines equipped with three speed Ford transmissions. Next came a series of sporting cars powered by the twin-ignition straight eight Nash engine or the Lincoln V12 unit. On the commercial side of the business Jensen’s were the leaders in the field of the design and construction of high-strength light alloys in commercial vehicles and produced a range of alloy bodied trucks and busses powered by either four-cylinder Ford engines, Ford V8s, or Perkins diesels. World War Two saw sports car production put aside and attentions were turned to more appropriate activities such as producing revolving tank gun turrets, explosives and converting the Sherman Tank for amphibious use in the D-Day invasion of Europe. -

British Motor Corporation and Leyland Motor Corporation Photographs, 1963-1970. Archival Collection 104

British Motor Corporation and Leyland Motor Corporation photographs, 1963-1970. Archival Collection 104 British Motor Corporation and Leyland Motor Corporation photographs, 1963-1970. Archival Collection 104 Revs Institute Page 1 of 3 British Motor Corporation and Leyland Motor Corporation photographs, 1963-1970. Archival Collection 104 Title: British Motor Corporation and Leyland Motor Corporation photographs, 1963-1970. Creator: Camisasca, Henry P. Call Number: Archival Collection 104 Quantity: 1 linear foot (1 clamshell binder) Abstract: The British Motor Corporation and Leyland Motor Corporation photographs, 1963- 1970 consist of 713 color image slides from the 12 Hours of Sebring at the Sebring International Raceway. Language: Materials are in English. Biography: British Motor Corporation was a UK based vehicle manufacturer founded in 1952. Some car models included the Austin, MG, Morris, Riley, and Wolseley. In 1966, BMC merged with Jaguar Cars Limited and Pressed Steel to become British Motor Holdings Limited (BMH). Leyland Motor Corporation was a British vehicle manufacturer founded in 1896 that began by producing lorries, buses, and trolleybuses. They were involved in tank production during WWII, creating the Cromwell Tank. In 1968 British Motor Holdings and Leyland Motor Corporation merged to become British Leyland after being nationalized. British Leyland faced financial difficulties in 1974 and the main surviving organizations are Mini and Jaguar Land Rover. Acquisition Note: Accession number: 2019-004 Access Restrictions: The British Motor Corporation and Leyland Motor Corporation photographs, 1963-1970 are open for research. Publication Rights: Copyright has been assigned to the Revs Institute. Although copyright was transferred by the donor, copyright in some items in the collection may still be held by their respective creator. -

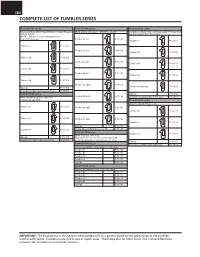

Complete List of Tumbler Series

184 COMPLETE LIST OF TUMBLER SERIES P-13-101/104 series P-13-131/144 series P-14-121/125 series Mercedes-Benz, BMW, General Motors, Eagle, Daewoo, BMW using 4-track keys – S7BWP / HU58AP Land Rover, Range Rover, Sterling using X170 type keys Suzuki, Saturn (ignition locks & some door locks) NOTE: This series is interchangeable with P-21-111/114 series. Tumbler #1 left P-13-131 Tumbler #1 P-14-121 Tumbler #1 P-13-101 Tumbler #2 left P-13-132 Tumbler #2 P-14-122 Tumbler #2 P-13-102 Tumbler #3 left P-13-133 Tumbler #3 P-14-123 Tumbler #3 P-13-103 Tumbler #4 left P-13-134 Tumbler #4 P-14-124 Tumbler #4 P-13-104 Tumbler #1 right P-13-141 Tumbler #2 alternate P-14-125 Springs P-31-100 Keying kit containing this series only A-13-101 P-13-121/123 series Springs P-31-100 Tumbler #2 right P-13-142 BMW (deadlocking door locks only) Keying kit containing this series only A-14-101 using X144 type keys P-14-131/133 series Jaguar using X177 type keys Tumbler #1 P-13-121 Tumbler #3 right P-13-143 Tumbler #1 P-14-131 Tumbler #2 P-13-122 Tumbler #4 right P-13-144 Tumbler #2 P-14-132 Springs P-31-100 Tumbler #3 P-13-123 Keying kit containing this series only A-13-103 P-13-181/184 series Tumbler #3 P-14-133 BMW internal 2-track keys Springs P-31-100 Now use P-31-175-178 series (also VW / Audi) Keying kit containing this series only A-13-102 previously available in keying kit no. -

The Case of Nissan's Direct Investment in Great Britain and Its

Do State and Politics Matter? The Case of Nissan‘s Direct Investment in Great Britain and Its Implications for British Leyland Tommaso Pardi This essay looks at a quite neglected side of the history of foreign direct investment (FDI) and multinationals: the political and diplomatic negotiations that often surround FDI projects and their wider implications for both the investors and the indigenous companies that might be affected by the entrance of new competitors. From this perspective, the case study analyzed here is of great relevance: it is the first direct investment made by a Japanese carmaker in Europe, and it was negotiated from 1981 to 1984 between Nissan and the British government led by Margaret Thatcher, which was also at the time the owner of the ―national champion‖ British Leyland (BL). Funding BL while attracting a new powerful competitor seemed at the time and still appears today as a very contradictory strategy. The essay will show, however, that this strategy was coherent with the shift in political support from the ailing national carmaker to its first-tier suppliers. It will also provide some new insights into the more general debate concerning the decline of BL and the role that the state and politics have played in that story. Foreign direct investment (FDI) and strategies of internationalization by multinational companies are traditional subjects of research in business history.1 But the political and diplomatic negotiations that very often 1 Mira Wilkins, The Maturing of Multinational Enterprise: American Business Abroad from 1914 to 1970 (Cambridge, Mass., 1974); Mira Wilkins, The History Tommaso Pardi <[email protected]> is a doctoral candidate in history at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales and is affiliated with Cultures et Sociétés Urbaines–CNRS, Paris. -

September 2020

Vol 38 No 9 September 2020 It’s been a very humid and wet month, not conducive for driv- Prez Sez ing the LBC’s with the top down. I did take advantage of a short somewhat cool morning and rolled the Mercedes on the By Dave Rosato rotisserie out of the garage and gave the entire car a coating of sandable primer. I’m at the finish stages of the body work. About a month ago I got a call from Patrick Lane. He took the Spitfire out for a drive and when he got home the engine started acting up. After shutting it off, it wouldn’t start again. He sug- gested a blown head gasket. So I suggested he trailer it over and we’d take a look at it. He bought a gasket set for the engine. When he brought it over, I thought I’d check the compression before pulling the head, just to confirm. I pulled all the plugs and put the gauge in number 4. Patrick cranked the engine. I immediately got showered with an oil/water mix coming out from the open spark plug holes. That confirmed a blown head gasket. We removed the carb and exhaust then the head bolts. We lifted the head and sure enough, #4 cylinder was full of water. It was interest- ing in that the top of the #4 piston was clean as new from being washed with hot water. We cleaned up the head and top of the block then put the engine back together with the new head gasket. -

Morris Garages Ltd, Then Morris Motors

Official name: Morris Garages Ltd, then Morris Motors, then The Nuffield Organisation, then British Motor Corporation, then British Motor Holdings, Leyland Motor Corporation, British Leyland Motor Corporation, British Leyland Limited, Austin Rover Group, then Rover Group, then MG Rover. The company went bankrupt in 2005. Owned by: Shanghai Automotive Industry Corporation. Current situation: MGs are now built in China, with a few assembled at the old MG factory in England. However, many car designs are very old and all are poorly built. MG has not been a a big hit in China and sales outside China have been dreadful. Chances of survival: poor. SAIC is staying alive thanks to Chinese government handouts and joint ventures with Western companies. If MG’s new owners are relying on Western sales to prosper, they are probably in for a lonely old age • 1 All content © The Dog & Lemon Guide 2016 • All rights reserved A brief history of MG (and why things went so badly wrong) WAS ORIGINALLY an abbreviation MGof Morris Garages. Founded in 1924 by William Morris, MG sportscars were based on the basic structure of Morris’s other cars from that era. MGs soon developed a reputation for being fast and nimble. Sales boomed. Originally owned personally by William Morris, MG was sold in 1935 to the Morris parent company. This put MG on a sound financial footing, but also made MG a tiny subsiduary of a major corporation. Uncredited images are believed to be in the public domain. Credited images are copyright their respective 2 All content © The Dog & Lemon Guide 2016 • All rights reserved owners. -

Expected in Such a Sale, Save for Formal Warranties to 1

No L 25/92 Official Journal of the European Communities 28 . 1 . 89 ' COMMISSION DECISION of 13 July 1988 concerning aid provided by the United Kingdom Government to the Rover Group, an undertaking producing motor vehicles (Only the English text is authentic) (89/58/EEC) THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Treaty, the other Member States and third parties were also given notice to submit their comments . Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, and in particular the first subparagraph of Article 93 (2) thereof, II Having given notice in accordance with the above Article to interested parties to submit their comments, The United Kingdom authorities presented their comments under the procedure by letters dated 29 April, Whereas : 18 May, 26 May, 6 June, 14 June, 7 July and 12 July 1988 providing detailed information on the precise terms of the agreement, on the restructuring efforts to be undertaken by Rover Group in the future, on the group's I activities, its financial and fiscal situation and its future prospects . I By letter of 14 March 1988 from its Permanent Represen tative the United Kingdom Government notified the In particular, the United Kingdom authorities Commission of its intention to provide new capital to the communicated the following principal terms of the sales Rover Group in the context of the sale of the remaining agreement which was reached on 29 March 1988 : car and jeep businesses of the group to British Aerospace. This notification followed a statement to the United — the United Kingdom Government intends to make a Kingdom Parliament on 1 March 1988 that British capital injection of £ 800 million into Rover Group to Aerospace had declared its interest in acquiring the eliminate the company's indebtedness, Government's shareholding in the company and it expected that negotiations on an exclusive basis would be — British Aerospace would immediately thereafter pay £ concluded by 30 April . -

TVR - the EVOLUTION & STORY – by Hi-Link Account Manager Angelo Bonvenuto

TVR - The EVOLUTION & STORY – By Hi-Link Account Manager Angelo Bonvenuto THE STORY – After selling my last motorcycle & having an empty “Short Bay” in my Garage I started looking for a toy to fill the space. Based on overall length it came down to a few options but I narrowed it down to a choice between a Lotus Elan & a TVR. The Lotus prices were about 3 times the TVR prices & that combined with parts availability along with several other factors like frame construction & my preference for a hard top it narrowed my search to the TVR. I found my car in MA in 2005 & the saga began. TVR is a handmade limited production English car that raided the British Leyland parts bin for many components thus it is an uncommon car made with common parts. The mid-engine cockpit to the rear, tubular steel chassis, 4 wheel independent suspension, fiberglass body & wide variety of engines makes it very innovative for its time. The TVR name comes from the consonants of the founder Trevor Wilkinson’s first name. My car is an “M-Series” which was named after Martin Lilley & was made for 5 years but TVR made a total worldwide production of only 947. The original 2500M was a good car for its day but the 3000M was a more balanced performance car & that was the “Resto-Mod” (restored / modified) car that I found. The legend was that the car was the object of a contentious divorce & the “Woman Scorned” set fire the 2500M. My goal was to put a V-8 into it eventually but the 3.0 liter engine spun a bearing so the process was accelerated.