BURNETT-DISSERTATION.Pdf (797.7Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lien Avec : I) Les Déchirures Continentales

L’Université Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah de Fès, Maroc En partenariat avec les Universités : Hassan II, Casablanca Cadi Ayyad, Marrakech Ibn Zohr, Agadir Chouaïb Doukkali, El Jadida Et AGRFM: Association des Géologues de la Région Fès-Meknès Organise ème Le 28 Colloque de Géologie Africaine CAG28 et La 18ème Assemblée Générale de la Société Géologique d’Afrique 9-17 Octobre 2021 Thème “Géosciences : Un substrat précieux pour le développement économique et social de l’Afrique” TROISIÈME CIRCULAIRE Programme Préliminaire Sous les auspices : De la Société Géologique d’Afrique (GSAf) Du Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale, de la Formation Professionnelle, de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche Scientifique Du ministère de l’Énergie, des Mines et de l’Environnement De l’Académie Hassan II des Sciences et Techniques Du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique et Technique Préambule Le colloque de Géologie Africaine est la plus importante manifestation géologique du continent organisée sous les auspices de la Société Géologique d’Afrique (GSAf). La 28ème édition (CAG28) se tiendra à l’Université Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah de Fès. Maroc. CAG28 a été reporté d’une année. Le programme énoncé dans la seconde circulaire est modifié, complété et repris ici. Nous espérons que la situation se sera améliorée d’ici l’automne prochain et que nous pourrons alors fêter ensemble la Géologie de notre cher continent. Le colloque couvrira toutes les disciplines des Sciences de la Terre et de l’Univers. Il propose jusqu’à présent : i) 19 thèmes. Chaque thème comporte une ou plusieurs sessions (32 sessions). Chaque session comportera une conférence dédiée ; ii) 6 conférences plénières ; iii) 7 ateliers de formation ; iv) 10 excursions couvrant l’ensemble des domaines structuraux du Maroc dont l’âge s’étale de l’Archéen au Quaternaire ; et v) un riche programme culturel. -

Marrakech Architecture Guide 2020

WHAT Architect WHERE Notes Completed in 2008, the terminal extension of the Marrakech Menara Airport in Morocco—designed by Swiss Architects E2A Architecture— uses a gorgeous facade that has become a hallmark of the airport. Light filters into the space by arabesques made up of 24 rhombuses and three triangles. Clad in white aluminum panels and featuring Marrakesh Menara stylized Islamic ornamental designs, the structure gives the terminal Airport ***** Menara Airport E2A Architecture a brightness that changes according to the time of day. It’s also an ال دول ي ال م نارة excellent example of how a contemporary building can incorporate مراك ش مطار traditional cultural motifs. It features an exterior made of 24 concrete rhombuses with glass printed ancient Islamic ornamental motives. The roof is constructed by a steel structure that continues outward, forming a 24 m canopy providing shade. Inside, the rhombuses are covered in white aluminum. ***** Zone 1: Medina Open both to hotel guests and visitors, the Delano is the perfect place to get away from the hustle and bustle of the Medina, and escape to your very own oasis. With a rooftop restaurant serving ،Av. Echouhada et from lunch into the evening, it is the ideal spot to take in the ** The Pearl Marrakech Rue du Temple magnificent sights over the Red City and the Medina, as well as the شارع دو معبد imperial ramparts and Atlas mountains further afield. By night, the daybeds and circular pool provide the perfect setting to take in the multicolour hues of twilight, as dusk sets in. Facing the Atlas Mountains, this 5 star hotel is probably one of the top spots in the city that you shouldn’t miss. -

Report of the United Nations Conference To

A/CONF.230/14 Report of the United Nations Conference to Support the Implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 14: Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development United Nations Headquarters 5-9 June 2017 United Nations New York, 2017 Note Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. [15 June 2017] Contents Chapter Page I. Resolutions adopted by the Conference ............................................. 5 II. Organization of work and other organizational matters ................................ 11 A. Date and venue of the Conference ............................................. 11 B. Attendance ................................................................ 11 C. Opening of the Conference................................................... 12 D. Election of the two Presidents and other officers of the Conference ................. 13 E. Adoption of the rules of procedure ............................................ 13 F. Adoption of the agenda of the Conference ...................................... 13 G. Organization of work, including the establishment of subsidiary bodies, and other organizational matters ....................................................... 14 H. Credentials of representatives to the Conference ................................. 14 I. Documentation ............................................................ 14 III. General debate ................................................................ -

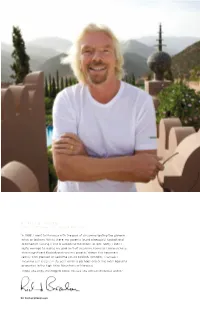

A Note from Sir Richard Branson

A NOTE FROM SIR RICHARD BRANSON “ In 1998, I went to Morocco with the goal of circumnavigating the globe in a hot air balloon. Whilst there, my parents found a beautiful Kasbah and dreamed of turning it into a wonderful Moroccan retreat. Sadly, I didn’t quite manage to realise my goal on that occasion, however I did purchase that magnificent Kasbah and now my parents’ dream has become a reality. I am pleased to welcome you to Kasbah Tamadot, (Tamadot meaning soft breeze in Berber), which is perhaps one of the most beautiful properties in the high Atlas Mountains of Morocco. I hope you enjoy this magical place; I’m sure you too will fall in love with it.” Sir Richard Branson 2- 5 THINGS YOU NEED TO KNOW 14 Babouches ACTIVITIES AT KASBAH Babysitting TAMADOT Cash and credit cards Stargazing Cigars Trekking in the Atlas Mountains Departure Asni Market Tours WELCOME TO KASBAH TAMADOT Do not disturb Cooking classes Fire evacuation routes Welcome to Kasbah Tamadot (pronounced: tam-a-dot)! Four legged friends We’re delighted you’ve come to stay with us. Games, DVDs and CDs This magical place is perfect for rest and relaxation; you can Kasbah Tamadot Gift Shop 1 5 do as much or as little as you like. Enjoy the fresh mountain air The Berber Boutique KASBAH KIDS as you wander around our beautiful gardens of specimen fruit Laundry and dry cleaning Activities for children trees and rambling rose bushes, or go on a trek through the Lost or found something? Medical assistance and pharmacy High Atlas Mountains...the choice is yours. -

Chapitre VI La Ville Et Ses Équipements Collectifs

Chapitre VI La ville et ses équipements collectifs Introduction L'intérêt accordé à la connaissance du milieu urbain et de ses équipements collectifs suscite un intérêt croissant, en raison de l’urbanisation accélérée que connaît le pays, et de son effet sur les équipements et les dysfonctionnements liés à la répartition des infrastructures. Pour résorber ce déséquilibre et assurer la satisfaction des besoins, le développement d'un réseau d'équipements collectifs appropriés s'impose. Tant que ce déséquilibre persiste, le problème de la marginalisation sociale, qui s’intensifie avec le chômage et la pauvreté va continuer à se poser La politique des équipements collectifs doit donc occuper une place centrale dans la stratégie de développement, particulièrement dans le cadre de l’aménagement du territoire. La distribution spatiale de la population et par conséquent des activités économiques, est certes liée aux conditions naturelles, difficiles à modifier. Néanmoins, l'aménagement de l'espace par le biais d'une politique active peut constituer un outil efficace pour mettre en place des conditions favorables à la réduction des disparités. Cette politique requiert des informations fiables à un niveau fin sur l'espace à aménager. La présente étude se réfère à la Base de données communales en milieu urbain (BA.DO.C) de 1997, élaborée par la Direction de la Statistique et concerne le niveau géographique le plus fin à savoir les communes urbaines, qui constituent l'élément de base de la décentralisation et le cadre d'application de la démocratie locale. Au recensement de 1982, était considéré comme espace urbain toute agglomération ayant un minimum de 1 500 habitants et qui présentait au moins quatre des sept conditions énumérées en infra1. -

The Origin and Development of the Lingua Franca”

Manuel Sedlaczek “The Origin and Development of the Lingua Franca” A historical linguistic study DIPLOMARBEIT zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Magister der Philosophie Studium: Anglistik und Amerikanistik Universität Klagenfurt Fakultät für Kulturwissenschaften Begutachter/in: O. Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Allan Richard James Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik November 2010 i Declaration of honour For Master’s Theses, Diploma Theses and Dissertations I hereby confirm on my honour that I personally prepared the present academic work and carried out myself the activities directly involved with it. I also confirm that I have used no resources other than those declared. All formulations and concepts adopted literally or in their essential content from printed, unprinted or Internet sources have been cited according to the rules for academic work and identified by means of footnotes or other precise indications of source. The support provided during the work, including significant assistance from my supervisor has been indicated in full. The academic work has not been submitted to any other examination authority. The work is submitted in printed and electronic form. I confirm that the content of the digital version is completely identical to that of the printed version. I am aware that a false declaration will have legal consequences. (Signature) (Place, date) ii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ....................................................................... 1 1.1 THE STUDY OF THE LINGUA FRANCA ............................................................. 1 1.2 HISTORICAL LINGUISTICS AND ANTHROPOLOGY ........................................... 4 1.3 THE CREATING OF HISTORY ............................................................................ 5 1.4 THE RE -INTEGRATION OF HISTORY ................................................................. 8 1.5 THE IMPORTANCE OF HISTORY ..................................................................... 10 CHAPTER 2: PROBLEMS CONCERNING THE LINGUA FRANCA ..... -

Pauvrete, Developpement Humain

ROYAUME DU MAROC HAUT COMMISSARIAT AU PLAN PAUVRETE, DEVELOPPEMENT HUMAIN ET DEVELOPPEMENT SOCIAL AU MAROC Données cartographiques et statistiques Septembre 2004 Remerciements La présente cartographie de la pauvreté, du développement humain et du développement social est le résultat d’un travail d’équipe. Elle a été élaborée par un groupe de spécialistes du Haut Commissariat au Plan (Observatoire des conditions de vie de la population), formé de Mme Ikira D . (Statisticienne) et MM. Douidich M. (Statisticien-économiste), Ezzrari J. (Economiste), Nekrache H. (Statisticien- démographe) et Soudi K. (Statisticien-démographe). Qu’ils en soient vivement remerciés. Mes remerciements vont aussi à MM. Benkasmi M. et Teto A. d’avoir participé aux travaux préparatoires de cette étude, et à Mr Peter Lanjouw, fondateur de la cartographie de la pauvreté, d’avoir été en contact permanent avec l’ensemble de ces spécialistes. SOMMAIRE Ahmed LAHLIMI ALAMI Haut Commissaire au Plan 2 SOMMAIRE Page Partie I : PRESENTATION GENERALE I. Approche de la pauvreté, de la vulnérabilité et de l’inégalité 1.1. Concepts et mesures 1.2. Indicateurs de la pauvreté et de la vulnérabilité au Maroc II. Objectifs et consistance des indices communaux de développement humain et de développement social 2.1. Objectifs 2.2. Consistance et mesure de l’indice communal de développement humain 2.3. Consistance et mesure de l’indice communal de développement social III. Cartographie de la pauvreté, du développement humain et du développement social IV. Niveaux et évolution de la pauvreté, du développement humain et du développement social 4.1. Niveaux et évolution de la pauvreté 4.2. -

Judeo-Provençal in Southern France

George Jochnowitz Judeo-Provençal in Southern France 1 Brief introduction Judeo-Provençal is also known as Judeo-Occitan, Judéo-Comtadin, Hébraïco- Comtadin, Hébraïco-Provençal, Shuadit, Chouadit, Chouadite, Chuadit, and Chuadite. It is the Jewish analog of Provençal and is therefore a Romance lan- guage. The age of the language is a matter of dispute, as is the case with other Judeo-Romance languages. It was spoken in only four towns in southern France: Avignon, Cavaillon, Caprentras, and l’Isle-sur-Sorgue. A women’s prayer book, some poems, and a play are the sources of the medieval language, and transcrip- tions of Passover songs and theatrical representations are the sources for the modern language. In addition, my own interviews in 1968 with the language’s last known speaker, Armand Lunel, provide data (Jochnowitz 1978, 1985). Lunel, who learned the language from his grandparents, not his parents, did not have occasion to converse in it. Judeo-Provençal/Shuadit is now extinct, since Armand Lunel died in 1977. Sometimes Jewish languages have a name meaning “Jewish,” such as Yiddish or Judezmo – from Hebrew Yehudit or other forms of Yehuda. This is the case with Shuadit, due to a sound change of /y/ to [š]. I use the name Judeo-Provençal for the medieval language and Shuadit for the modern language. 2 Historical background 2.1 Speaker community: Settlement, documentation Jews had lived in Provence at least as early as the first century CE. They were officially expelled from France in 1306, readmitted in 1315, expelled again in 1322, readmitted in 1359, and expelled in 1394 for a period that lasted until the French Revolution. -

The Insider's Guide to the World's Coolest Neighbourhoods

The Insider’s Guide to the World’s Coolest Neighbourhoods CONTENTS © Michael Abid / 500px; © f11photo / Shutterstock; © marchello74 / Shutterstock; © lazyllama / Shutterstock / Shutterstock; © marchello74 / Shutterstock; © f11photo © Michael Abid / 500px; © peeterv / Getty Images; © Daniel Fung / Shutterstock; © Yu Chun Christopher Wong / Shutterstock; © Elena Lar / Shutterstock © Elena Lar / Shutterstock; Wong Chun Christopher © Yu / Shutterstock; © peeterv / Getty Images; © Daniel Fung INTRODUCTION 4 Dubai 24 Hong Kong 58 Edinburgh 88 Berlin 134 NORTH AMERICA 172 Austin 216 New York City 260 Wellington 302 Buenos Aires 322 Seoul 64 London 92 Prague 144 San Francisco 174 New Orleans 224 Boston 270 Auckland 306 Rio de Janeiro 328 AFRICA & THE ASIA 30 Tokyo 68 Barcelona 100 Stockholm 150 Portland 182 Chicago 232 MIDDLE EAST 6 Mumbai 32 Paris 110 Budapest 154 Vancouver 188 Atlanta 240 OCEANIA 276 SOUTH AMERICA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 336 Marrakesh 8 Bangkok 38 EUROPE 78 Amsterdam 118 Istanbul 160 Seattle 196 Toronto 244 Perth 278 & THE CARIBBEAN 312 Cape Town 12 Singapore 46 Lisbon 80 Rome 122 Moscow 166 Los Angeles 202 Washington, DC 248 Melbourne 284 Lima 314 Tel Aviv 18 Beijing 52 Dublin 84 Copenhagen 130 Mexico City 210 Philadelphia 254 Sydney 292 Havana 318 INTRODUCTION It’s easy to fall in love with San Francisco. (p. 318), Austin (p. 216), Lima (p. 314) and But to understand what makes the city tick, Moscow (p. 166). We also included popular I needed to do a little sleuthing. cities that travellers think they know well – The first time I explored this preening blonde, beachy Sydney (p. 292); desert- peacock of a city, I dutifully toured its backed glamourpuss Dubai (p. -

Reasonable Plans. the Story of the Kasbah Du Toubkal

The Story of the Kasbah du Toubkal MARRAKECH • MOROCCO DEREK WORKMAN The Story of the Kasbah du Toubkal Marrakech • Morocco Derek WorkMan Second edition (2014) The information in this booklet can be used copyright free (without editorial changes) with a credit given to the Kasbah du Toubkal and/or Discover Ltd. For permission to make editorial changes please contact the Kasbah du Toubkal at [email protected], or tel. +44 (0)1883 744 392. Discover Ltd, Timbers, Oxted Road, Godstone, Surrey, RH9 8AD Photography: Alan Keohane, Derek Workman, Bonnie Riehl and others Book design/layout: Alison Rayner We are pleased to be a founding member of the prestigious National Geographic network Dedication Dreams are only the plans of the reasonable – dreamt by Discover realised by Omar and the Worker of Imlil (Inscription on a brass plaque at the entrance to the Kasbah du Toubkal) his booklet is dedicated to the people of Imlil, and to all those who Thelped bring the ‘reasonable plans’ to reality, whether through direct involvement with Discover Ltd. and the Kasbah du Toubkal, or by simply offering what they could along the way. Long may they continue to do so. And of course to all our guests who contribute through the five percent levy that makes our work in the community possible. CONTENTS IntroDuctIon .........................................................................................7 CHAPTER 1 • The House on the Hill .......................................13 CHAPTER 2 • Taking Care of Business .................................29 CHAPTER 3 • one hand clapping .............................................47 CHAPTER 4 • An Association of Ideas ...................................57 CHAPTER 5 • The Work of Education For All ....................77 CHAPTER 6 • By Bike Through the High Atlas Mountains .......................................99 CHAPTER 7 • So Where Do We Go From Here? .......... -

MPLS VPN Service

MPLS VPN Service PCCW Global’s MPLS VPN Service provides reliable and secure access to your network from anywhere in the world. This technology-independent solution enables you to handle a multitude of tasks ranging from mission-critical Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP), Customer Relationship Management (CRM), quality videoconferencing and Voice-over-IP (VoIP) to convenient email and web-based applications while addressing traditional network problems relating to speed, scalability, Quality of Service (QoS) management and traffic engineering. MPLS VPN enables routers to tag and forward incoming packets based on their class of service specification and allows you to run voice communications, video, and IT applications separately via a single connection and create faster and smoother pathways by simplifying traffic flow. Independent of other VPNs, your network enjoys a level of security equivalent to that provided by frame relay and ATM. Network diagram Database Customer Portal 24/7 online customer portal CE Router Voice Voice Regional LAN Headquarters Headquarters Data LAN Data LAN Country A LAN Country B PE CE Customer Router Service Portal PE Router Router • Router report IPSec • Traffic report Backup • QoS report PCCW Global • Application report MPLS Core Network Internet IPSec MPLS Gateway Partner Network PE Router CE Remote Router Site Access PE Router Voice CE Voice LAN Router Branch Office CE Data Branch Router Office LAN Country D Data LAN Country C Key benefits to your business n A fully-scalable solution requiring minimal investment -

Liste Des Revendeurs Des Pesticides a Usage Agricole

LISTE DES REVENDEURS DES PESTICIDES A USAGE AGRICOLE MISE A JOUR : 12 JANVIER 2021 Région : BENI MELLAL -KHENIFRA Commune / Province Ville / Localité Nom Adresse BENI MELLAL AGRIMATCO RUE 20 AOUT OULED MBAREK N°61 BENI MELLAL OULED IYAICH ESPACE HORTICOLE TADLA DOUAR RQUABA OULED YAICH BENI MELLAL OULED M'BAREK PHYTO BOUTRABA RUE 20 AOUT OULED MBAREK BENI MELLAL BENI MELLAL AGROPHARMA 33 AVENUE DES FAR BENI MELLAL BENI MELLAL COMPTOIR AGRICOLE DU SOUSS AGROPOLE IL14 LOT N°01OULED M’BAREK BENI MELLAL BENI MELLAL FILAHATI ELAMRIYA 2, HAY EL FATH N°1 BÉNI MELLAL BENI MELLAL COMMERCIALE SIHAM ROUTE DE MARRAKECH KM3 BENI MELLAL BENI MELLAL PROMAGRI TERRAIN 02 N°10 ZONE INDUSTRIELLE BENI MELLAL PROMAGRI LOTISSEMENT 10 QUARTIER INDUSTRIELLE BENI MELLAL ALPHACHIMIE RUE HASSSAN 2, OULED HEMDANE, DAR JDIDADA, BENI MELLAL AGHBALA AGRI-PHYTO AGHBALA QUARTIER ADMINSTRATIF AGHBALA BENI MELLAL KASBAT DU TADLA COMPTOIR AGRICOLE DU TADLA RUE FATIMA EL FIHRIA N 14 TADLA QUARTIER ADMINISTRATIF BENI MELLAL BOUAZZAOUI AVENU EL AYOUN, RUE 1, N°80 BENI MELLAL BENI MELLAL STE MATJAR ANAFA 146 AVENUE DES FAR BENI MELLAL BENI MELLAL OUADID EL MAATI 57 AVENUE DES FAR BENI MELLAL BENI MELLAL FELLAH TADLA 30 AVENUE DES FAR , UNITE COMMERCIALE BENI MELLAL SIDI JABEUR ESPACE AGRI ERRAHMA ROUTE NATIONALE N11 ,LOT ENNAJAH SIDI JABEUR SIDI JABEUR OUDIDI MUSTAPHA RUE1 N 61 SIDI JBEUR SIDI JABEUR KAMAL KANNANE LOT ENNAJAH 2 N 109 SIDI JABEUR DIR EL KSSIBA STE BOUCHAGRO CENTRE IGHREM LAALAM OULED M'BAREK IMAGRI BVD 20 AOUT , ROUTE DE MARRAKECH , OULED MBAREK BENI MELLAL