Reasonable Plans. the Story of the Kasbah Du Toubkal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marrakech Architecture Guide 2020

WHAT Architect WHERE Notes Completed in 2008, the terminal extension of the Marrakech Menara Airport in Morocco—designed by Swiss Architects E2A Architecture— uses a gorgeous facade that has become a hallmark of the airport. Light filters into the space by arabesques made up of 24 rhombuses and three triangles. Clad in white aluminum panels and featuring Marrakesh Menara stylized Islamic ornamental designs, the structure gives the terminal Airport ***** Menara Airport E2A Architecture a brightness that changes according to the time of day. It’s also an ال دول ي ال م نارة excellent example of how a contemporary building can incorporate مراك ش مطار traditional cultural motifs. It features an exterior made of 24 concrete rhombuses with glass printed ancient Islamic ornamental motives. The roof is constructed by a steel structure that continues outward, forming a 24 m canopy providing shade. Inside, the rhombuses are covered in white aluminum. ***** Zone 1: Medina Open both to hotel guests and visitors, the Delano is the perfect place to get away from the hustle and bustle of the Medina, and escape to your very own oasis. With a rooftop restaurant serving ،Av. Echouhada et from lunch into the evening, it is the ideal spot to take in the ** The Pearl Marrakech Rue du Temple magnificent sights over the Red City and the Medina, as well as the شارع دو معبد imperial ramparts and Atlas mountains further afield. By night, the daybeds and circular pool provide the perfect setting to take in the multicolour hues of twilight, as dusk sets in. Facing the Atlas Mountains, this 5 star hotel is probably one of the top spots in the city that you shouldn’t miss. -

FAO-GIAHS: Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems a Legacy for the Future!

FAO-GIAHS: Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems A LEGACY FOR THE FUTURE! Our Efforts on Biodiversity in Our Strategy on Biodiversity Do you believe in the role of Development Cooperation Our Aichi Priorities family farming communities espe- FACT 1 goal cially women in conservation and A sustainable use of biodiversity ? Leverage global and national recognition of Mainstreaming the importance of agricultural heritage systems 2 3 and its biodiversity for their institutional support Integration 1 4 Awareness Place your post-its with and safeguard 5 Jane dela Cruz ©FAO/Mary 0 Incentives 2 Resource Mobilization your answer below: Resources 6 Photo: FACT 2 Sustainable Use Use of Natural goal 1 to 20 The Aichi 9 Supporting active and informed participation of Biodiversity B 1 Loss of Habitats 7 Knowledge E Targets goal The GIAHS Initiative in China have brought significant indigenous and local communities in biodiversity Sustainable Fisheries Enhancing Areas Under Sust. Management 8 Implementation 8 Pollution development in Qingtian, our government and local management and conservation Traditional Knowledge 1 9 Invasive Alien Species community have come to understand the value of our V FACT 3 Short Term ulnerable Ecosystems National Biodiversity 1 7 Strategies traditional rice fish culture and biodiversity. Agriculture is 0 1 Coordination and harmonization of activities to a way of our lives and to live in harmony with nature... Protected Areas Agricultural Biodiversity Preventing Extinctions promote efficient management of resources and 1 Access and 1 6 Benefit Sharing “Traditional rice fish provides us organic food products, which sells higher than 1 encourage multi-stakeholder participation Medium Term non-organic, and making our annual higher than before. -

Tradition and Sustainability in Vernacular Architecture of Southeast Morocco

sustainability Article Tradition and Sustainability in Vernacular Architecture of Southeast Morocco Teresa Gil-Piqueras * and Pablo Rodríguez-Navarro Centro de Investigación en Arquitectura, Patrimonio y Gestión para el Desarrollo Sostenible–PEGASO, Universitat Politècnica de València, Cno. de Vera, s/n, 46022 Valencia, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This article is presented after ten years of research on the earthen architecture of southeast- ern Morocco, more specifically that of the natural axis connecting the cities of Midelt and Er-Rachidia, located North and South of the Moroccan northern High Atlas. The typology studied is called ksar (ksour, pl.). Throughout various research projects, we have been able to explore this territory, documenting in field sheets the characteristics of a total of 30 ksour in the Outat valley, 20 in the mountain range and 53 in the Mdagra oasis. The objective of the present work is to analyze, through qualitative and quantitative data, the main characteristics of this vernacular architecture as a perfect example of an environmentally respectful habitat, obtaining concrete data on its traditional character and its sustainability. The methodology followed is based on case studies and, as a result, we have obtained a typological classification of the ksour of this region and their relationship with the territory, as well as the social, functional, defensive, productive, and building characteristics that define them. Knowing and puttin in value this vernacular heritage is the first step towards protecting it and to show our commitment to future generations. Keywords: ksar; vernacular architecture; rammed earth; Morocco; typologies; oasis; High Atlas; sustainable traditional architecture Citation: Gil-Piqueras, T.; Rodríguez-Navarro, P. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 13 April 2015 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Kaislaniemi, L. and van Hunen, J. (2014) 'Dynamics of lithospheric thinning and mantle melting by edge-driven convection : application to Moroccan Atlas mountains.', Geochemistry, geophysics, geosystems., 15 (8). pp. 3175-3189. Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/2014GC005414 Publisher's copyright statement: c 2014. The Authors. This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License, which permits use and distribution in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and no modications or adaptations are made. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk PUBLICATIONS Geochemistry, -

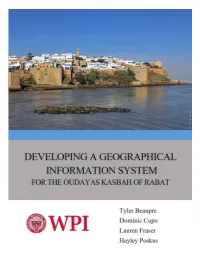

Developing a Geographical Information System for the Oudayas Kasbah of Rabat

Developing a Geographical Information System for the Oudayas Kasbah of Rabat An Interactive Qualifying Project (IQP) Proposal submitted to the faculty of Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelors of Science in cooperation with The Prefecture of Rabat Submitted by: Project Advisors: Tyler Beaupre Professor Ingrid Shockey Dominic Cupo Professor Gbetonmasse Somasse Lauren Fraser Hayley Poskus Submitted to: Mr. Hammadi Houra, Sponsor Liaison Submitted on October 12th, 2016 ABSTRACT An accurate map of a city is essential for supplementing tourist traffic and management by the local government. The city of Rabat was lacking such a map for the Kasbah of the Oudayas. With the assistance of the Prefecture of Rabat, we created a Geographical Information System (GIS) for that section of the medina using QGIS software. Within this GIS, we mapped the area, added historical landmarks and tourist attractions, and created a walking tour of the Oudayas Kasbah. This prototype remains expandable, allowing the prefecture to extend the system to all the city of Rabat. i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction In 2012, the city of Rabat, Morocco was awarded the status of a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) world heritage site for integrating both Western Modernism and Arabo-Muslim history, creating a unique juxtaposition of cultures (UNESCO, 2016). The Kasbah of the Oudayas, a twelfth century fortress in the city, exemplifies this connection. A view of the Bab Oudaya is shown below in Figure 1. It is a popular tourist attraction and has assisted Rabat in bringing in an average of 500,000 tourists per year (World Bank, 2016). -

A Note from Sir Richard Branson

A NOTE FROM SIR RICHARD BRANSON “ In 1998, I went to Morocco with the goal of circumnavigating the globe in a hot air balloon. Whilst there, my parents found a beautiful Kasbah and dreamed of turning it into a wonderful Moroccan retreat. Sadly, I didn’t quite manage to realise my goal on that occasion, however I did purchase that magnificent Kasbah and now my parents’ dream has become a reality. I am pleased to welcome you to Kasbah Tamadot, (Tamadot meaning soft breeze in Berber), which is perhaps one of the most beautiful properties in the high Atlas Mountains of Morocco. I hope you enjoy this magical place; I’m sure you too will fall in love with it.” Sir Richard Branson 2- 5 THINGS YOU NEED TO KNOW 14 Babouches ACTIVITIES AT KASBAH Babysitting TAMADOT Cash and credit cards Stargazing Cigars Trekking in the Atlas Mountains Departure Asni Market Tours WELCOME TO KASBAH TAMADOT Do not disturb Cooking classes Fire evacuation routes Welcome to Kasbah Tamadot (pronounced: tam-a-dot)! Four legged friends We’re delighted you’ve come to stay with us. Games, DVDs and CDs This magical place is perfect for rest and relaxation; you can Kasbah Tamadot Gift Shop 1 5 do as much or as little as you like. Enjoy the fresh mountain air The Berber Boutique KASBAH KIDS as you wander around our beautiful gardens of specimen fruit Laundry and dry cleaning Activities for children trees and rambling rose bushes, or go on a trek through the Lost or found something? Medical assistance and pharmacy High Atlas Mountains...the choice is yours. -

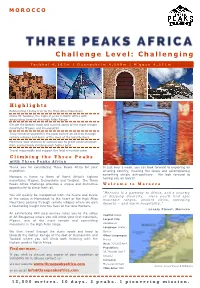

Challenge Level: Challenging

MOROCCO Challenge Level: Challenging Toubkal 4,167m | O u a n o u k r i m 4 , 0 8 9 m | M ’ g o u n 4 , 0 7 1 m H i g h l i g h t s Exhilarating 10 day trek to the High Atlas Mountains Climb Mt Toubkal, the highest peak in North Africa with astounding views of the High Atlas Range Get off the beaten track and summit some of the most remote mountains M’goun and Ouanoukrim Truly immerse yourself in the local culture as we trek through remote villages and learn of the lives of the local Berbers Maximise your chances of success due to great acclimatisation from successively climbing each higher peak Travel responsibly and support the local mountain crew Climbing the Three Peaks with Three Peaks Africa Thank you for considering Three Peaks Africa for your In just over a week, you can look forward to exploring an expedition. amazing country, meeting the locals and accomplishing something simply extraordinary. We look forward to Morocco is home to three of North Africa’s highest having you on board! mountains; M’goun, Ouanoukrim and Toubkal. The Three Peaks Africa Challenge provides a unique and distinctive Welcome to Morocco opportunity to climb them all. “Morocco is a gateway to Afr ica, and a country You will quickly be transported from the hustle and bustle of d iz zy ing d ivers ity . Here you’ ll f ind ep ic of the souks in Marrakech to the heart of the High Atlas mountain ranges, anc ie nt c ities, sweeping Mountains passing through remote villages where we gain deserts – and warm hospitality .” a fascinating insight into the lives of the local Berbers. -

Pauvrete, Developpement Humain

ROYAUME DU MAROC HAUT COMMISSARIAT AU PLAN PAUVRETE, DEVELOPPEMENT HUMAIN ET DEVELOPPEMENT SOCIAL AU MAROC Données cartographiques et statistiques Septembre 2004 Remerciements La présente cartographie de la pauvreté, du développement humain et du développement social est le résultat d’un travail d’équipe. Elle a été élaborée par un groupe de spécialistes du Haut Commissariat au Plan (Observatoire des conditions de vie de la population), formé de Mme Ikira D . (Statisticienne) et MM. Douidich M. (Statisticien-économiste), Ezzrari J. (Economiste), Nekrache H. (Statisticien- démographe) et Soudi K. (Statisticien-démographe). Qu’ils en soient vivement remerciés. Mes remerciements vont aussi à MM. Benkasmi M. et Teto A. d’avoir participé aux travaux préparatoires de cette étude, et à Mr Peter Lanjouw, fondateur de la cartographie de la pauvreté, d’avoir été en contact permanent avec l’ensemble de ces spécialistes. SOMMAIRE Ahmed LAHLIMI ALAMI Haut Commissaire au Plan 2 SOMMAIRE Page Partie I : PRESENTATION GENERALE I. Approche de la pauvreté, de la vulnérabilité et de l’inégalité 1.1. Concepts et mesures 1.2. Indicateurs de la pauvreté et de la vulnérabilité au Maroc II. Objectifs et consistance des indices communaux de développement humain et de développement social 2.1. Objectifs 2.2. Consistance et mesure de l’indice communal de développement humain 2.3. Consistance et mesure de l’indice communal de développement social III. Cartographie de la pauvreté, du développement humain et du développement social IV. Niveaux et évolution de la pauvreté, du développement humain et du développement social 4.1. Niveaux et évolution de la pauvreté 4.2. -

The Insider's Guide to the World's Coolest Neighbourhoods

The Insider’s Guide to the World’s Coolest Neighbourhoods CONTENTS © Michael Abid / 500px; © f11photo / Shutterstock; © marchello74 / Shutterstock; © lazyllama / Shutterstock / Shutterstock; © marchello74 / Shutterstock; © f11photo © Michael Abid / 500px; © peeterv / Getty Images; © Daniel Fung / Shutterstock; © Yu Chun Christopher Wong / Shutterstock; © Elena Lar / Shutterstock © Elena Lar / Shutterstock; Wong Chun Christopher © Yu / Shutterstock; © peeterv / Getty Images; © Daniel Fung INTRODUCTION 4 Dubai 24 Hong Kong 58 Edinburgh 88 Berlin 134 NORTH AMERICA 172 Austin 216 New York City 260 Wellington 302 Buenos Aires 322 Seoul 64 London 92 Prague 144 San Francisco 174 New Orleans 224 Boston 270 Auckland 306 Rio de Janeiro 328 AFRICA & THE ASIA 30 Tokyo 68 Barcelona 100 Stockholm 150 Portland 182 Chicago 232 MIDDLE EAST 6 Mumbai 32 Paris 110 Budapest 154 Vancouver 188 Atlanta 240 OCEANIA 276 SOUTH AMERICA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 336 Marrakesh 8 Bangkok 38 EUROPE 78 Amsterdam 118 Istanbul 160 Seattle 196 Toronto 244 Perth 278 & THE CARIBBEAN 312 Cape Town 12 Singapore 46 Lisbon 80 Rome 122 Moscow 166 Los Angeles 202 Washington, DC 248 Melbourne 284 Lima 314 Tel Aviv 18 Beijing 52 Dublin 84 Copenhagen 130 Mexico City 210 Philadelphia 254 Sydney 292 Havana 318 INTRODUCTION It’s easy to fall in love with San Francisco. (p. 318), Austin (p. 216), Lima (p. 314) and But to understand what makes the city tick, Moscow (p. 166). We also included popular I needed to do a little sleuthing. cities that travellers think they know well – The first time I explored this preening blonde, beachy Sydney (p. 292); desert- peacock of a city, I dutifully toured its backed glamourpuss Dubai (p. -

REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY of AFRICA. Uganda Certificate of Education

REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY OF AFRICA. Uganda Certificate of Education. GEOGRAPHY Code: 273/2, Paper 2 2 hours 30 minutes PART I : THE REST OF AFRICA. INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES: This paper consists of two sections: Part I Rest of Africa. Answer two questions from part I @ question carry 25marks. Any additional question (s) answered will not be marked. Four questions are set and a candidate is required to answer only two questions. This region covers 50% of paper 273/2. 1) Download and print out a hard copy then copy this notes in a fresh book for Rest of Africa paper2. 2) If You need a copy of this work organized by the teacher for Rest of Africa. Call 0775 534057 for a book of Africa and it will be delivered. Emihen – Utec 1 SIZE, SHAPE AND POSITION. POSITION OF AFRICA. Africa is one of the largest continents of the world. It’s the second to the largest landmass combined of Eurasia i.e. Europe and Asia continents. LOCATION: Africa lies between latitudes 37.51’N just West of Cape Blanc in Tunisia to Cape Aghulhas at Latitude 34.51’S a distance of 8,000kms. Africa also lies between Cape Ras Hagun 51.50’E and Cape Verde 17.32’W. SIZE: Africa covers land area of about 30,300,300km2. THE SHAPE: Africa’s shape is unbalanced; with her northern part being bulky and wide, while the southern part being thinner and narrower in appearance. Emihen-Utec 2 The Latitude EQUATOR divides the continent into TWO HALVES, there being approximately; 3800kms between the Cape Agulhas in the south and Equator while between Tunisia and Equator in the North is 4,100kms. -

Climbing in the Atlas Mountains a Survey

HAMISH BROWN Climbing in the Atlas Mountains A Survey (Plates 24-27) magine a country with eighty per cent sunshine throughout the year, I grand mountain scenery, its rock climbing potential barely touched, all within easy reach, with no political hassles orcostly fees, and a lovely people. It may sound too good to be true but it all exists in Europe's nearest truly exotic foreign country: Morocco. The Atlas Mountains, which sweep across from north-east to south-west, separating 'the desert and the sown', offer a climber's paradise. Quite why the Atlas has suffered neglect by climbers from Britain is hard to understand. Perhaps the names are too difficult - there's no kudos in reporting unpronounceable climbs - or the information is hidden away in French publications. 1 Time the cat escaped from out of the bag. I spent a winter in the Atlas in 1965 and repeated this delight in 1966. Having gone there specifically to climb (Notes in AJ 1966) I ended simply hooked on the whole Atlas ambience and began to wander rather than be restricted to one area. The natural outcome of this was an end-to-end trek 2 in 1995 : 96 days, 900 miles and about 30 peaks bagged. Farfrom rounding off my knowledge, the trip introduced me to a score of new worthy areas to visit and I've had five Atlas months every year since. 3 The scope for climbing is vast. The country must have 50 limestone gorges, miles long and up to 2000 feet deep, each ofwhich would fill volumes ofclimbs if located in Europe, while on the mountains there are crests to be traversed and notable granite faces still virgin. -

Africa: Physical Geography

R E S O U R C E L I B R A R Y E N C Y C L O P E D I C E N T RY Africa: Physical Geography Africa has an array of diverse ecosystems, from sandy deserts to lush rain forests. G R A D E S 6 - 12+ S U B J E C T S Biology, Ecology, Earth Science, Geology, Geography, Physical Geography C O N T E N T S 10 Images For the complete encyclopedic entry with media resources, visit: http://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/africa-physical-geography/ Africa, the second-largest continent, is bounded by the Mediterranean Sea, the Red Sea, the Indian Ocean, and the Atlantic Ocean. It is divided in half almost equally by the Equator. Africas physical geography, environment and resources, and human geography can be considered separately. Africa has eight major physical regions: the Sahara, the Sahel, the Ethiopian Highlands, the savanna, the Swahili Coast, the rain forest, the African Great Lakes, and Southern Africa. Some of these regions cover large bands of the continent, such as the Sahara and Sahel, while others are isolated areas, such as the Ethiopian Highlands and the Great Lakes. Each of these regions has unique animal and plant communities. Sahara The Sahara is the worlds largest hot desert, covering 8.5 million square kilometers (3.3 million square miles), about the size of the South American country of Brazil. Defining Africa's northern bulge, the Sahara makes up 25 percent of the continent. The Sahara has a number of distinct physical features, including ergs, regs, hamadas, and oases.