Climbing in the Atlas Mountains a Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Initiation Au Maroc

INITIATION AU MAROC INSTITUT DES HAUTES ÉTUDES MAROCAINES INITIATION AU MAROC Nouvelle édition mise à jour VANOEST LES EDITIONS D'ART ET D'HISTOIRE I)i\ R 1 S MCMXLV OAT COLLABORÉ A CET OUVRAGE : 1 MM. É. LÉVI-PROVENÇAL, directeur honoraire de l'Institut des Hautes Études Marocaines, professeur à la Faculté des Lettres d'Alger. J. CÉLÉRIER, directeur d'études de géographie à l'Institut des Hautes Études Marocaines. G. S. COLIN, directeur d'études de linguistique nord-afri- caine à l'Institut des Hautes Études Marocaines, pro- fesseur à l'École des Langues orientales. L EMBERGER, ancien chef du service botanique à l'Institut Scientifique Chérifien, professeur à la Faculté des Sciences de Montpellier. E. LAOUST, directeur d'études honoraire de dialectes berbè- res à l'Institut des Hautes Études Marocaines. Le docteur H.-P.-J. RENAUD, directeur d'études d'histoire des sciences à l'Institut des Hautes Études Marocaines. HENRI TERRASSE, directeur de l'Institut des Hautes Études Marocaines, correspondant de l'Institut. II MM. RENÉ HOFFHERR, maître des requêtes au Conseil d'État, an- cien directeur des Centres d'études juridiques et admi- nistratives \à l'Institut des Hautes Études Marocaines. PAUL MAUCHAUSSÉ, MARCEL BOUSSER et JACQUES MTLLERON, maîtres de conférences aux Centres d'études juridi- ques et administratives. HENRI MAZOYER, contrôleur civil, CLAUDE ECORCHEVILLE, J. PLASSE et JEAN FINES, contrôleurs civils adjoints. J. VALLET, Chef du Bureau de documentation économique au Service du Commerce. AVANT-PROPOS DE LA PREMIÈRE ÉDITION (1932) Jusqu'à une date récente, le Français qui arrivait au Ma- roc recevait un choc : du premier coup, une impression puissante d'étrangeté, de dépaysement le saisissait. -

Moroccan Climbing: Rock, Sun and Snow

PAUL KNOTT Moroccan Climbing: Rock, Sun and Snow OroCCO fascinates me. It has a rich complexity, retaining an alluring M mystique despite being well travelled and documented. During 1998 and 1999 I was lucky enough to get a real insight into the country and its climbing through a post at the delightful Al Akhawayn University in the Middle Atlas Mountains. Here I give a flavour of the rock climbing, skiing and mountain walking, all of them spiced with the cultural interest inherent in Morocco's mountain country. After three days' driving from the UK, I sped through dry limestone plateaux to Ifrane with its promise of sunshine and snow. I found myself sharing an office with Michael Peyron - Alpine Club member, Atlas guidebook author and Berber expert. Along with other companions, we escaped at weekends to explore the wealth of lesser-known mountains a short drive from the fairy-tale campus. We sought and found crags and mountains with European-style ease of access. For big, unexplored rock climbs one of my favourite places was the Dades Gorge. This was visited by Trevor Jones and Les Brown in 1990, but otherwise seems to have seen little or no climbing. Above Boumalne-de Dades the valley becomes strikingly beautiful, with its kasbahs and its unusual rock features (doigts de singes or monkey fingers) set amongst emerald green jardins. On my first visit we got no further than this; the downpour sent raging torrents across the road and stranded us at Ait-Arbi. We found the doigts disappointing for climbing. I returned some weeks later, to the gorge itself. -

A Note from Sir Richard Branson

A NOTE FROM SIR RICHARD BRANSON “ In 1998, I went to Morocco with the goal of circumnavigating the globe in a hot air balloon. Whilst there, my parents found a beautiful Kasbah and dreamed of turning it into a wonderful Moroccan retreat. Sadly, I didn’t quite manage to realise my goal on that occasion, however I did purchase that magnificent Kasbah and now my parents’ dream has become a reality. I am pleased to welcome you to Kasbah Tamadot, (Tamadot meaning soft breeze in Berber), which is perhaps one of the most beautiful properties in the high Atlas Mountains of Morocco. I hope you enjoy this magical place; I’m sure you too will fall in love with it.” Sir Richard Branson 2- 5 THINGS YOU NEED TO KNOW 14 Babouches ACTIVITIES AT KASBAH Babysitting TAMADOT Cash and credit cards Stargazing Cigars Trekking in the Atlas Mountains Departure Asni Market Tours WELCOME TO KASBAH TAMADOT Do not disturb Cooking classes Fire evacuation routes Welcome to Kasbah Tamadot (pronounced: tam-a-dot)! Four legged friends We’re delighted you’ve come to stay with us. Games, DVDs and CDs This magical place is perfect for rest and relaxation; you can Kasbah Tamadot Gift Shop 1 5 do as much or as little as you like. Enjoy the fresh mountain air The Berber Boutique KASBAH KIDS as you wander around our beautiful gardens of specimen fruit Laundry and dry cleaning Activities for children trees and rambling rose bushes, or go on a trek through the Lost or found something? Medical assistance and pharmacy High Atlas Mountains...the choice is yours. -

Rowan C. Martindale Curriculum Vitae Associate Professor (Invertebrate Paleontology) at the University of Texas at Austin

ROWAN C. MARTINDALE CURRICULUM VITAE ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR (INVERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY) AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN Department of Geological Sciences E-mail: [email protected] Jackson School of Geosciences Website: www.jsg.utexas.edu/martindale/ 2275 Speedway Stop C9000 Orchid ID: 0000-0003-2681-083X Austin, TX 78712-1722 Phone: 512-475-6439 Office: JSG 3.216A RESEARCH INTERESTS The overarching theme of my work is the connection between Earth and life through time, more precisely, understanding ancient (Mesozoic and Cenozoic) ocean ecosystems and the evolutionary and environmental events that shaped them. My research is interdisciplinary, (paleontology, sedimentology, biology, geochemistry, and oceanography) and focuses on: extinctions and carbon cycle perturbation events (e.g., Oceanic Anoxic Events, acidification events); marine (paleo)ecology and reef systems; the evolution of reef builders (e.g., coral photosymbiosis); and exceptionally preserved fossil deposits (Lagerstätten). ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Associate Professor, University of Texas at Austin September 2020 to Present Assistant Professor, University of Texas at Austin August 2014 to August 2020 Postdoctoral Researcher, Harvard University August 2012 to July 2014 Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology; Mentor: Dr. Andrew H. Knoll. EDUCATION Doctorate, University of Southern California 2007 to 2012 Dissertation: “Paleoecology of Upper Triassic reef ecosystems and their demise at the Triassic-Jurassic extinction, a potential ocean acidification event”. Advisor: Dr. David J. Bottjer, degree conferred August 7th, 2012. Bachelor of Science Honors Degree, Queen’s University 2003 to 2007 Geology major with a general concentration in Biology (Geological Sciences Medal Winner). AWARDS AND RECOGNITION Awards During Tenure at UT Austin • 2019 National Science Foundation CAREER Award: Awarded to candidates who are judged to have the potential to serve as academic role models in research and education. -

Crustal Versus Asthenospheric Origin of the Relief of the Atlas Mountains of Morocco

Crustal versus asthenospheric origin of the relief of the Atlas Mountains of Morocco. Y. Missenard, H. Zeyen, D. Frizon de Lamotte, P. Leturmy, C. Petit, M. Sebrier To cite this version: Y. Missenard, H. Zeyen, D. Frizon de Lamotte, P. Leturmy, C. Petit, et al.. Crustal versus astheno- spheric origin of the relief of the Atlas Mountains of Morocco.. Journal of Geophysical Research, American Geophysical Union, 2006, 111, pp.B03401. 10.1029/2005JB003708. hal-00092374 HAL Id: hal-00092374 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00092374 Submitted on 1 Mar 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 111, B03401, doi:10.1029/2005JB003708, 2006 Crustal versus asthenospheric origin of relief of the Atlas Mountains of Morocco Yves Missenard,1 Hermann Zeyen,2 Dominique Frizon de Lamotte,1 Pascale Leturmy,1 Carole Petit,3 Michel Se´brier,3 and Omar Saddiqi4 Received 2 March 2005; revised 18 October 2005; accepted 9 November 2005; published 1 March 2006. [1] We investigate the respective roles of crustal tectonic shortening and asthenospheric processes on the topography of the High Atlas and surrounding areas (Morocco). -

New Distribution Notes for Terrestrial Herpetofauna from Morocco

North-Western Journal of Zoology Vol. 6, No. 2, 2010, pp.309-315 P-ISSN: 1584-9074, E-ISSN: 1843-5629 Article No.: 061208 New distribution notes for terrestrial herpetofauna from Morocco D. James HARRIS1,2*, Ana PERERA1, Mafalda BARATA1,2,3, Pedro TARROSO1 and Daniele SALVI1 1. CIBIO-UP, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Campus Agrário de Vairão, 4485-661 Vairão, Portugal. 2. Departamento de Biologia, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade do Porto, 4099-002 Porto, Portugal. 3. Universitat de Biologia, Dep. Biologia Animal, Av. Diagonal, 645, 08028 Barcelona, Spain. *Corresponding author: D.J. Harris, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Additional data on the distribution of terrestrial herpetofauna from Morocco are pre- sented, based on fieldwork carried out in March and May 2008. Thirty-eight species were recorded from 78 localities. Some of these represent considerable range extensions for the species, indicating that more prospection is needed to complement the existing knowledge of herpetofauna from this country. Key words: Distribution, Morocco, reptiles, amphibians Morocco covers an area of over 400,000 km2 in sions for several species (e.g. Fahd et al. 2008, Northwest Africa, and has the highest diversity Harris et al. 2008), indicating that more field- of herpetofauna in the Western Mediterranean work is necessary to precisely delimit the region. Together with Tunisia and Algeria it ranges of many species and subspecies. Here forms the Maghreb, a well defined bio- we report the findings of two trips to Morocco, geographic entity. Including a wide variety of carried out in March and May 2008, both of habitats, from Saharan through to Mediterra- approximately 2 weeks. -

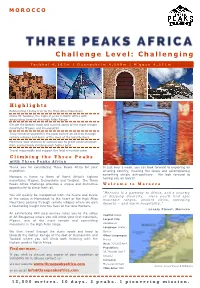

Challenge Level: Challenging

MOROCCO Challenge Level: Challenging Toubkal 4,167m | O u a n o u k r i m 4 , 0 8 9 m | M ’ g o u n 4 , 0 7 1 m H i g h l i g h t s Exhilarating 10 day trek to the High Atlas Mountains Climb Mt Toubkal, the highest peak in North Africa with astounding views of the High Atlas Range Get off the beaten track and summit some of the most remote mountains M’goun and Ouanoukrim Truly immerse yourself in the local culture as we trek through remote villages and learn of the lives of the local Berbers Maximise your chances of success due to great acclimatisation from successively climbing each higher peak Travel responsibly and support the local mountain crew Climbing the Three Peaks with Three Peaks Africa Thank you for considering Three Peaks Africa for your In just over a week, you can look forward to exploring an expedition. amazing country, meeting the locals and accomplishing something simply extraordinary. We look forward to Morocco is home to three of North Africa’s highest having you on board! mountains; M’goun, Ouanoukrim and Toubkal. The Three Peaks Africa Challenge provides a unique and distinctive Welcome to Morocco opportunity to climb them all. “Morocco is a gateway to Afr ica, and a country You will quickly be transported from the hustle and bustle of d iz zy ing d ivers ity . Here you’ ll f ind ep ic of the souks in Marrakech to the heart of the High Atlas mountain ranges, anc ie nt c ities, sweeping Mountains passing through remote villages where we gain deserts – and warm hospitality .” a fascinating insight into the lives of the local Berbers. -

Quaternary Glaciations of the Atlas Mountains, North Africa

The University of Manchester Research Quaternary Glaciations of the Atlas Mountains, North Africa DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53447-7.00076-3 Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Hughes, P. D., Fenton, C. R., & Gibbard, P. L. (2011). Quaternary Glaciations of the Atlas Mountains, North Africa. In Developments in Quaternary Science|Dev. Quat. Sci. (Vol. 15, pp. 1065-1074). Elsevier BV. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53447-7.00076-3 Published in: Developments in Quaternary Science|Dev. Quat. Sci. Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:03. Oct. 2021 Provided for non-commercial research and educational use only. Not for reproduction, distribution or commercial use. This chapter was originally published in the book Developments in Quaternary Science, Vol.15, published by Elsevier, and the attached copy is provided by Elsevier for the author's benefit and for the benefit of the author's institution, for non- commercial research and educational use including without limitation use in instruction at your institution, sending it to specific colleagues who know you, and providing a copy to your institution’s administrator. -

Nostalgias in Modern Tunisia Dissertation

Images of the Past: Nostalgias in Modern Tunisia Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By David M. Bond, M.A. Graduate Program in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: Sabra J. Webber, Advisor Johanna Sellman Philip Armstrong Copyrighted by David Bond 2017 Abstract The construction of stories about identity, origins, history and community is central in the process of national identity formation: to mould a national identity – a sense of unity with others belonging to the same nation – it is necessary to have an understanding of oneself as located in a temporally extended narrative which can be remembered and recalled. Amid the “memory boom” of recent decades, “memory” is used to cover a variety of social practices, sometimes at the expense of the nuance and texture of history and politics. The result can be an elision of the ways in which memories are constructed through acts of manipulation and the play of power. This dissertation examines practices and practitioners of nostalgia in a particular context, that of Tunisia and the Mediterranean region during the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Using a variety of historical and ethnographical sources I show how multifaceted nostalgia was a feature of the colonial situation in Tunisia notably in the period after the First World War. In the postcolonial period I explore continuities with the colonial period and the uses of nostalgia as a means of contestation when other possibilities are limited. -

Reasonable Plans. the Story of the Kasbah Du Toubkal

The Story of the Kasbah du Toubkal MARRAKECH • MOROCCO DEREK WORKMAN The Story of the Kasbah du Toubkal Marrakech • Morocco Derek WorkMan Second edition (2014) The information in this booklet can be used copyright free (without editorial changes) with a credit given to the Kasbah du Toubkal and/or Discover Ltd. For permission to make editorial changes please contact the Kasbah du Toubkal at [email protected], or tel. +44 (0)1883 744 392. Discover Ltd, Timbers, Oxted Road, Godstone, Surrey, RH9 8AD Photography: Alan Keohane, Derek Workman, Bonnie Riehl and others Book design/layout: Alison Rayner We are pleased to be a founding member of the prestigious National Geographic network Dedication Dreams are only the plans of the reasonable – dreamt by Discover realised by Omar and the Worker of Imlil (Inscription on a brass plaque at the entrance to the Kasbah du Toubkal) his booklet is dedicated to the people of Imlil, and to all those who Thelped bring the ‘reasonable plans’ to reality, whether through direct involvement with Discover Ltd. and the Kasbah du Toubkal, or by simply offering what they could along the way. Long may they continue to do so. And of course to all our guests who contribute through the five percent levy that makes our work in the community possible. CONTENTS IntroDuctIon .........................................................................................7 CHAPTER 1 • The House on the Hill .......................................13 CHAPTER 2 • Taking Care of Business .................................29 CHAPTER 3 • one hand clapping .............................................47 CHAPTER 4 • An Association of Ideas ...................................57 CHAPTER 5 • The Work of Education For All ....................77 CHAPTER 6 • By Bike Through the High Atlas Mountains .......................................99 CHAPTER 7 • So Where Do We Go From Here? .......... -

Biscutella, Ser

El género Biscutella, ser. Biscutella: aspectos taxonómicos, nomenclaturales y filogenéticos Alicia Vicente Caviedes Instituto de la Biodiversidad-CIBIO Facultad de Ciencias El género Biscutella, ser. Biscutella: aspectos taxonómicos, nomenclaturales y filogenéticos Tesis Doctoral Memoria presentada por Alicia Vicente Caviedes para aspirar al grado de DOCTOR POR LA UNIVERSIDAD DE ALICANTE Biodiversidad y Conservación Bajo la dirección de: María Ángeles Alonso Vargas y Manuel Benito Crespo Villalba Alicante, septiembre 2017 ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN ........................................................................................................... 1 El tratamiento infragenérico ................................................................................................................. 2 Aspectos morfológicos ......................................................................................................................... 4 Número cromosómicos ...................................................................................................................... 12 Antecedentes históricos ..................................................................................................................... 13 Estudios moleculares ......................................................................................................................... 20 Objetivos generales ............................................................................................................................ 21 Material y métodos ........................................................................................................................... -

Download Download

BORN IN THE MEDITERRANEAN: Alicia Vicente,3 Ma Angeles´ Alonso,3 and COMPREHENSIVE TAXONOMIC Manuel B. Crespo3* REVISION OF BISCUTELLA SER. BISCUTELLA (BRASSICACEAE) BASED ON MORPHOLOGICAL AND PHYLOGENETIC DATA1,2 ABSTRACT Biscutella L. ser. Biscutella (5 Biscutella ser. Lyratae Malin.) comprises mostly annual or short-lived perennial plants occurring in the Mediterranean basin and the Middle East, which exhibit some diagnostic floral features. Taxa in the series have considerable morphological plasticity, which is not well correlated with clear geographic or ecologic patterns. Traditional taxonomic accounts have focused on a number of vegetative and floral characters that have proved to be highly variable, a fact that contributed to taxonomic inflation mostly in northern Africa. A detailed study and re-evaluation of morphological characters, together with recent phylogenetic data based on concatenation of two plastid and one nuclear region sequence data, yielded the basis for a taxonomic reappraisal of the series. In this respect, a new comprehensive integrative taxonomic arrangement for Biscutella ser. Biscutella is presented in which 10 taxa are accepted, namely seven species and three additional varieties. The name B. eriocarpa DC. is reinterpreted and suggested to include the highest morphological variation found in northern Morocco. Its treatment here accepts two varieties, one of which is described as new (B. eriocarpa var. riphaea A. Vicente, M. A.´ Alonso & M. B. Crespo). In addition, the circumscriptions of several species, such as B. boetica Boiss. & Reut., B. didyma L., B. lyrata L., and B. maritima Ten., are revisited. Nomenclatural types, synonymy, brief descriptions, cytogenetic data, conservation status, distribution maps, and identification keys are included for the accepted taxa, with seven lectotypes and one epitype being designated here.