Garces-Mascarenas-Labour Migra WT-01.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boletín Oficial Del Estado

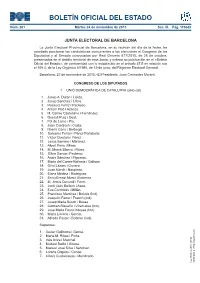

BOLETÍN OFICIAL DEL ESTADO Núm. 281 Martes 24 de noviembre de 2015 Sec. III. Pág. 110643 JUNTA ELECTORAL DE BARCELONA La Junta Electoral Provincial de Barcelona, en su reunión del día de la fecha, ha acordado proclamar las candidaturas concurrentes a las elecciones al Congreso de los Diputados y al Senado convocadas por Real Decreto 977/2015, de 26 de octubre, presentadas en el ámbito territorial de esta Junta, y ordena su publicación en el «Boletín Oficial del Estado», de conformidad con lo establecido en el artículo 47.5 en relación con el 169.4, de la Ley Orgánica 5/1985, de 19 de junio, del Régimen Electoral General. Barcelona, 23 de noviembre de 2015.–El Presidente, Joan Cremades Morant. CONGRESO DE LOS DIPUTADOS 1. UNIÓ DEMOCRÀTICA DE CATALUNYA (unio.cat) 1. Josep A. Duran i Lleida. 2. Josep Sanchez i Llibre. 3. Rosaura Ferriz i Pacheco. 4. Antoni Picó i Azanza. 5. M. Carme Castellano i Fernández. 6. Queralt Puig i Gual. 7. Pol de Lamo i Pla. 8. Joan Contijoch i Costa. 9. Noemi Cano i Berbegal. 10. Salvador Ferran i Pérez-Portabella. 11. Víctor Gonzalo i Pérez. 12. Jesús Serrano i Martínez. 13. Albert Peris i Miras. 14. M. Mercè Blanco i Ribas. 15. Sílvia Garcia i Pacheco. 16. Anaïs Sánchez i Figueras. 17. Maria del Carme Ballesta i Galiana. 18. Oriol Lázaro i Llovera. 19. Joan March i Naspleda. 20. Elena Medina i Rodríguez. 21. Enric-Ernest Munt i Gutierrez. 22. M. Jesús Cucurull i Farré. 23. Jordi Lluís Bailach i Aspa. 24. Eva Cordobés i Millán. -

«Este Es Un Daño Directo Del Independentismo»

EL MUNDO. MARTES 21 DE NOVIEMBRE DE 2017 43 ECONOMÍA i culo 155 en Cataluña es lo que ha impedido que Barcelona terminara DINERO como sede de la EMA. En un men- FRESCO saje en Twitter, calificó de «éxito del 155» que la capital catalana hubiera CARLOS sido eliminada de la carrera. Puigdemont recordó que hasta SEGOVIA el pasado 1 de octubre, fecha del referéndum ilegal, Barcelona «era España no da la favorita» para acoger este orga- nismo europeo. «Con violencia, re- una en la UE troceso democrático y el 155, el Estado la ha sentenciado», conclu- yó el ex mandatario autonómico. Los gobiernos de la UE decidieron En la misma línea se pronunció que no sólo Ámsterdam y Milán, si- el portavoz parlamentario del PDe- no incluso Copenhague –que está CAT, Carles Campuzano, quien fuera del euro– y Bratislava –cuyo afirmó que el Gobierno «no ha es- mejor aeropuerto es el de Viena– tado a la altura». eran candidatas más válidas que En un comentario publicado en Barcelona. La Ciudad Condal, que su cuenta personal de Twitter, el in- ofrecía la Torre Agbar como sede y dependentista catalán asume que el apoyo de una de las más sólidas no ganar la sede de la EMA es, «sin agencias estatales del medicamento duda, una mala noticia», si bien re- como no pasó de primera ronda, lo calca que «ni Cataluña ni Barcelo- que puede calificarse de humillación. na son quienes han fallado». A su Culpar de este fiasco totalmente al juicio, es el Gobierno quien «no ha Gobierno central como ha hecho el estado a la altura» y recuerda que ya ex presidente de la Generalitat, el Ejecutivo del PP es el principal Carles Puigdemont o parcialmente responsable ante la UE. -

The Spanish Gay and Lesbian Movement in Comparative

Instituto Juan March Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Ciencias Sociales (CEACS) Juan March Institute Center for Advanced Study in the Social Sciences (CEACS) Pursuing membership in the polity : the Spanish gay and lesbian movement in comparative perspective, 1970-1997 Author(s): Calvo, Kerman Year: 2005 Type Thesis (doctoral) University: Instituto Juan March de Estudios e Investigaciones, Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Ciencias Sociales, University of Essex, 2004. City: Madrid Number of pages: ix, 298 p. Abstract: El título de la tesis de Kerman Calvo Borobia es Pursuing membership in the polity: the Spanish gay and lesbian movement in comparative perspective, (1970–1997). Lo que el estudio aborda es por qué determinados movimientos sociales varían sus estrategias ante la participación institucional. Es decir, por qué pasan de rechazar la actuación dentro del sistema político a aceptarlo. ¿Depende ello del contexto político y de cambios sociales? ¿Depende de razones debidas al propio movimiento? La explicación principal radica en las percepciones políticas y los mapas intelectuales de los activistas, en las variaciones de estas percepciones a lo largo del tiempo según distintas experiencias de socialización. Atribuye por el contrario menor importancia a las oportunidades políticas, a factores exógenos al propio movimiento, al explicar los cambios en las estrategias de éste. La tesis analiza la evolución en el movimiento de gays y de lesbianas en España desde una perspectiva comparada, a partir de su nacimiento en los años 70 hasta final del siglo, con un importante cambio hacia una estrategia de incorporación institucional a finales de los años 80. La tesis fue dirigida por la profesora Yasemin Soysal, miembro del Consejo Científico, y fue defendida en la Universidad de Essex. -

Report of the United Nations Conference To

A/CONF.230/14 Report of the United Nations Conference to Support the Implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 14: Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development United Nations Headquarters 5-9 June 2017 United Nations New York, 2017 Note Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. [15 June 2017] Contents Chapter Page I. Resolutions adopted by the Conference ............................................. 5 II. Organization of work and other organizational matters ................................ 11 A. Date and venue of the Conference ............................................. 11 B. Attendance ................................................................ 11 C. Opening of the Conference................................................... 12 D. Election of the two Presidents and other officers of the Conference ................. 13 E. Adoption of the rules of procedure ............................................ 13 F. Adoption of the agenda of the Conference ...................................... 13 G. Organization of work, including the establishment of subsidiary bodies, and other organizational matters ....................................................... 14 H. Credentials of representatives to the Conference ................................. 14 I. Documentation ............................................................ 14 III. General debate ................................................................ -

Labour Migration from Indonesia

LABOUR MIGRATION FROM INDONESIA IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benets migrants and society. As an intergovernmental body, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and wellbeing of migrants. This publication is produced with the generous nancial support of the Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration (United States Government). Opinions expressed in this report are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reect the views of IOM. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher: International Organization for Migration Mission in Indonesia LABOUR MIGRATION FROM INDONESIA Sampoerna Strategic Square, North Tower Floor 12A Jl. Jend. Sudirman Kav. 45-46 An Overview of Indonesian Migration to Selected Destinations in Asia and the Middle East Jakarta 12930 Indonesia © 2010 International Organization for Migration (IOM) IOM International Organization for Migration IOM International Organization for Migration Labour Migration from Indonesia TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii PREFACE ix EXECUTIVE SUMMARY xi ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS 1 INTRODUCTION 3 Purpose 3 Terminology 3 Methodology -

Julio Loras, Albert Fabà Aquellos Polvos Trajeron Estos Lodos. Diálogos Postelectorales Diciembre De 2019

Julio Loras, Albert Fabà Aquellos polvos trajeron estos lodos. Diálogos postelectorales Diciembre de 2019. La preocupación sobre el crecimiento de Vox dio lugar a un diálogo, a vuelapluma y poco sistemático, entre Julio Loras, biólogo y Alber Fabà, sociolingüista. Esas reflexiones se publicaron en Pensamiento crítico en su edición de enero. Ahora siguen dialogando, pero en este caso sobre el resultado de las últimas elecciones generales, la reacción en Catalunya a la sentencia del procés o la posibilidad de un gobierno de coalición que, en el momento en que se han redactado estas notas, aún no ha cuajado, a consecuencia de las dudas sobre la abstención (o no) de ERC en la investidura. ALBERT. Durante los últimos meses me acuerdo a menudo de Borgen, la serie de ficción en la cual tiene un notable protagonismo Kasper Juul, responsable de prensa de Birgitte Nyborg, primera ministra de Dinamarca. ¿Conoces la saga? JULIO. Hace mucho tiempo que no veo ni cine ni series. Llegaron a aburrirme. Por lo general, veía desde el principio por dónde iban a ir los tiros y perdían todo aliciente para mí. Aunque tengo algo de idea sobre esa serie por los medios. Creo que va de asesores de los políticos. ¿No es así? A. Exacto. Me viene al pelo, por eso del papel que parece que ha tenido Ivan Redondo en las decisiones que se han tomado en el PSOE, des de la moción de censura a Rajoy hasta ahora. Redondo es un típico asesor “profesional”. Que yo sepa, asesoró al candidato del PP en las municipales de Badalona en 2011. -

Title Protecting and Assisting Refugees and Asylum-Seekers in Malaysia

Title Protecting and assisting refugees and asylum-seekers in Malaysia : the role of the UNHCR, informal mechanisms, and the 'Humanitarian exception' Sub Title Author Lego, Jera Beah H. Publisher Global Center of Excellence Center of Governance for Civil Society, Keio University Publication year 2012 Jtitle Journal of political science and sociology No.17 (2012. 10) ,p.75- 99 Abstract This paper problematizes Malaysia's apparently contradictory policies – harsh immigration rules applied to refugees and asylum seekers on the one hand, and the continued presence and functioning of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) on the other hand. It asks how it has been possible to protect and assist refugees and asylum seekers in light of such policies and how such protection and assistance is implemented, justified, and maintained. Giorgio Agamben's concept of the state of exception is employed in analyzing the possibility of refugee protection and assistance amidst an otherwise hostile immigration regime and in understanding the nature of juridical indeterminacy in which refugees and asylum seekers in Malaysia inhabit. I also argue that the exception for refugees in Malaysia is a particular kind of exception, that is, a 'humanitarian exception.' Insofar as the state of exception is decided on by the sovereign, in Carl Schmitt's famous formulation, I argue that it is precisely in the application of 'humanitarian exception' for refugees and asylum seekers that the Malaysian state is asserting its sovereignty. As for the protection and assistance to refugees and asylum seekers, it remains an exception to the rule. In other words, it is temporary, partial, and all together insufficient for the preservation of the dignity of refugees and asylum seekers. -

Malaysian Chinese Ethnography

MALAYSIAN CHINESE ETHNOGRAPHY Introduction The Chinese are quickly becoming world players in areas of business, economics, and technology. At least one in five persons on the planet are of a Chinese background. Chinese are immigrating all over the globe at a rate that may eclipse any historical figure. These immigrants, known as overseas Chinese, are exerting tremendous influence on the communities they live in. This ethnography will focus specifically on those overseas Chinese living in urban Malaysia. Malaysian Chinese have developed a unique culture that is neither mainland Chinese nor Malay. In order to propose a strategy for reaching them with the gospel several historical and cultural considerations must first be examined. This paper will provide a history of Chinese immigration to Malaysia, then explore the unique Chinese Malay culture, and finally will present a strategy for reaching the Malaysian Chinese with a culturally appropriate method. It will be demonstrated that a successful strategy will take into account the unique culture of Malaysian Chinese, including reshaping the animistic worldview, finding a solution to the practice of ancestor worship by redeeming the cultural rituals, and delivering biblical teaching through a hybrid oral/literate style. History of Immigration Malaysia has long been influenced by travelling cultures and neighboring nations. Halfway between India and China, Malaysia has been influenced by both. Historically, India has had more influence on Malaysia than has China. The primary reason is that the Chinese have 1 2 long been a self-sustaining empire, seeing themselves as the center of the world (zhong guo) and were not prone to long sea voyages. -

Illegal Immigration to Singapore Siew Hoon

ILLEGAL IMMIGRATION TO SINGAPORE SIEW HOON TAN A thesis submitted in fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts School of History and Philosophy University of N.S.W February, 2009 ~~ ntf! UN~!IIT'f(W' _ tovlll 'fIl,lIU.I n IPllI .... ' _.r ...... _r..... - fW __£WHODN ~,- 'It • .""............._" ... -- _ ItlllOllY ~ _ 08l)II0('>' .. ~ - r......, N\'TII KICW. 8ClENC£1 r.. U£OotC. ~T1CH ..lIlNGM'CIIt: - I ~gapore 1& I COWltry built entllety by m!gram.. The topic of ~mlon thus fonm a very mpolUnc put of the hlsllCNy of SIngapore, In wllkh mudllftftrth IIn bMn <!oM. Ho.,•.,. one uPKt of the "lOde< " migration h"'tory of Sl~ hill not been _Il-.tudild, and tMI .. -.gal Immlgtllltkln. SIne, centuries 8gO, ~~ been smUO\lItd Ofl" very W;J~'" th.t modem 51"0'110'" _ Its prospertty to. Today, people .... ~ll enlltring and Illting the ~ntry c:lolIndesdnaly Iaing the __ w,",.",ys. Ho••••r. _ tKhnology dI.lICi'P'I. ttll ~by which ltIeH ~.. UH to Inter SingapoR c:IIMMllnely .re eonsmntly cIwInglng. R~1eM of the ehangot In methods, loch c:llIndestlM mlgntlXln on.n lnvol¥ft; gI'Mt clang....nd hardship for ItIoM who d.... to .,.,blltlf on lhe founwy. Jutt .. lhe WlIy It w.. In lhe pIIll. This III 1...ln man ~ I' SlnglpoN tum. from • colony to In lndl!*'dent eotlnlry, .nd II the Independent oov-mmll1t InctNllngly ufi'Cls.. mOAl control on lhe typll of Immlgl1lnts It .1I0WI Into Its ~nt to MIp tth tht c:ountry to IItHter heights In term. -

Palau De La Musica Catalana De Barcelona 36

Taula de contingut CITES 7 La Vanguardia - Catalán - 21/01/2018 "El ideal de justicia" con Javier del Pino, José Martí Gómez, José Mª Mena, José Mª Fernández Seijo y 8 Mateo Seguí que junto a Lourdes Lancho comentan la sentencia del Caso Palau que se dio a conocer .... Cadena Ser - A VIVIR QUE SON DOS DIAS - 21/01/2018 Ana Pastor, Javier Maroto, Juan Carlos Girauta, Carles Campuzano, Óscar Puente, Joan Tardá y Pablo 10 Echenique debaten sobre la corrupción política que afecta a partidos como el PP o CDC. LA SEXTA - EL OBJETIVO - 21/01/2018 Javier del Pino, Quique Peinado, Antonio Castelo y David Navarro comentan en clave de humor noticias 12 de la semana: caso Palau, trama Púnica, rama valenciana de la Gürtel, etc. Cadena Ser - A VIVIR QUE SON DOS DIAS - 20/01/2018 Entrevista a Mónica Oltra, vicepresidenta de la Generalitat Valenciana, para hablar de asuntos como los 13 recortes del gobierno, las pensiones, la corrupción en el PP y en la antigua Convergéncia o la .... LA SEXTA - LA SEXTA NOCHE - 20/01/2018 Iñaki López y los contertulios Ester Capella, Joan Mena, Maribel Martínez, Esperanza García, Lorena 16 Roldán y Carles Rivas debaten sobre la corrupción política, especialmente los casos juzgados esta .... LA SEXTA - LA SEXTA NOCHE - 20/01/2018 Iñaki López y los contertulios Ester Capella, Joan Mena, Maribel Martínez, Esperanza García, Lorena 19 Roldán y Carles Rivas debaten sobre el caso Palau de la Música y cómo afecta al PdeCAT, antigua .... LA SEXTA - LA SEXTA NOCHE - 20/01/2018 Iñaki López y el periodista Carlos Quílez analizan el caso de corrupción en Cataluña relacionado con el 21 caso Palau de la Música y cómo afecta al PdeCAT, antigua Convergència. -

Preses I Presos Bascos Al País Basc

Drets humans. Solucions. Pau. Preses i presos bascos al País Basc. Deixant enrere un conflicte que s’ha allargat massa, tant en temps com en patiment, al País Basc s’han obert noves oportunitats per construir un escenari de pau. Les converses i els acords adoptats entre diferents agents del País Basc, l’alto-el-foc d’ETA i la implicació i ajuda de la comunitat internacional, han obert el camí per solucionar el conflicte basc. Aquest ha deixat conseqüències de tot tipus i totes han de ser solucionades. Per avançar-hi, cal posar atenció també a la situació dels i les ciutadanes que a causa del conflicte estan empresonades o a l’exili, dispersats a centenars de quilometres del País Basc, amb el patiment afegit que suposa tant per a ells i elles com per als seus familiars. Com a primer pas, doncs, creiem que cal respectar els drets humans bàsics dels presos i preses basques. Respecte que comporta: · Traslladar al País Basc a tots el presos i preses bascos. · Alliberar els presos i preses amb malalties greus. · Acabar amb la prolongació de les condemnes i derogar les mesures que comporten la cadena perpètua. · Respectar tots els drets humans que els corresponen com a presos i com a persones. Per tal de reclamar als estats espanyol i francès que facin passos cap a una solució democràtica, les persones sotasignants subscrivim aquestes reivindicacions amb l’esperit d’impulsar-les des de Catalunya. I, alhora, donem suport a la mobilització del proper 12 de gener a Bilbao, convocada p e r Herrira -plataforma en defensa dels drets dels presos bascos-, amb l’adhesió d’un ampli suport social, així com de nombroses personalitats de la cultura, l’esport i la política basca. -

The Impact on Domestic Policy of the EU Code of Conduct on Arms Exports the Czech Republic, the Netherlands and Spain

The Impact on Domestic Policy of the EU Code of Conduct on Arms Exports The Czech Republic, the Netherlands and Spain SIPRI Policy Paper No. 21 Mark Bromley Stockholm International Peace Research Institute May 2008 © SIPRI, 2008 ISSN 1652-0432 (print) ISSN 1653-7548 (online) Printed in Sweden by CM Gruppen, Bromma Contents Contents iii Preface iv Abbreviations v 1. Introduction 1 2. EU engagement in arms export policies 5 The origins of the EU Code of Conduct 5 The development of the EU Code of Conduct since 1998 9 The impact on the framework of member states’ arms export policies 11 The impact on the process of member states’ arms export policies 12 The impact on the outcomes of member states’ arms export policies 13 Box 2.1. Non-EU multilateral efforts in the field of arms export policies 6 3. Case study: the Czech Republic 17 The Czech Republic’s engagement with the EU Code of Conduct 17 The impact on the framework of Czech arms export policy 19 The impact on the process of Czech arms export policy 21 The impact on the outcomes of Czech arms export policy 24 Box 3.1. Key Czech legislation on arms export controls 18 Table 3.1. Czech exports of military equipment, 1997–2006 24 4. Case study: the Netherlands 29 The Netherlands’ engagement with the EU Code of Conduct 29 The impact on the framework of Dutch arms export policy 31 The impact on the process of Dutch arms export policy 32 The impact on the outcomes of Dutch arms export policy 34 Box 4.1.