The Spanish Gay and Lesbian Movement in Comparative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boletín Oficial Del Estado

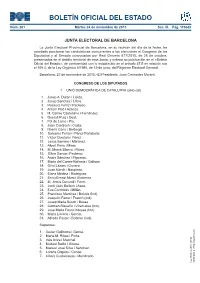

BOLETÍN OFICIAL DEL ESTADO Núm. 281 Martes 24 de noviembre de 2015 Sec. III. Pág. 110643 JUNTA ELECTORAL DE BARCELONA La Junta Electoral Provincial de Barcelona, en su reunión del día de la fecha, ha acordado proclamar las candidaturas concurrentes a las elecciones al Congreso de los Diputados y al Senado convocadas por Real Decreto 977/2015, de 26 de octubre, presentadas en el ámbito territorial de esta Junta, y ordena su publicación en el «Boletín Oficial del Estado», de conformidad con lo establecido en el artículo 47.5 en relación con el 169.4, de la Ley Orgánica 5/1985, de 19 de junio, del Régimen Electoral General. Barcelona, 23 de noviembre de 2015.–El Presidente, Joan Cremades Morant. CONGRESO DE LOS DIPUTADOS 1. UNIÓ DEMOCRÀTICA DE CATALUNYA (unio.cat) 1. Josep A. Duran i Lleida. 2. Josep Sanchez i Llibre. 3. Rosaura Ferriz i Pacheco. 4. Antoni Picó i Azanza. 5. M. Carme Castellano i Fernández. 6. Queralt Puig i Gual. 7. Pol de Lamo i Pla. 8. Joan Contijoch i Costa. 9. Noemi Cano i Berbegal. 10. Salvador Ferran i Pérez-Portabella. 11. Víctor Gonzalo i Pérez. 12. Jesús Serrano i Martínez. 13. Albert Peris i Miras. 14. M. Mercè Blanco i Ribas. 15. Sílvia Garcia i Pacheco. 16. Anaïs Sánchez i Figueras. 17. Maria del Carme Ballesta i Galiana. 18. Oriol Lázaro i Llovera. 19. Joan March i Naspleda. 20. Elena Medina i Rodríguez. 21. Enric-Ernest Munt i Gutierrez. 22. M. Jesús Cucurull i Farré. 23. Jordi Lluís Bailach i Aspa. 24. Eva Cordobés i Millán. -

«Este Es Un Daño Directo Del Independentismo»

EL MUNDO. MARTES 21 DE NOVIEMBRE DE 2017 43 ECONOMÍA i culo 155 en Cataluña es lo que ha impedido que Barcelona terminara DINERO como sede de la EMA. En un men- FRESCO saje en Twitter, calificó de «éxito del 155» que la capital catalana hubiera CARLOS sido eliminada de la carrera. Puigdemont recordó que hasta SEGOVIA el pasado 1 de octubre, fecha del referéndum ilegal, Barcelona «era España no da la favorita» para acoger este orga- nismo europeo. «Con violencia, re- una en la UE troceso democrático y el 155, el Estado la ha sentenciado», conclu- yó el ex mandatario autonómico. Los gobiernos de la UE decidieron En la misma línea se pronunció que no sólo Ámsterdam y Milán, si- el portavoz parlamentario del PDe- no incluso Copenhague –que está CAT, Carles Campuzano, quien fuera del euro– y Bratislava –cuyo afirmó que el Gobierno «no ha es- mejor aeropuerto es el de Viena– tado a la altura». eran candidatas más válidas que En un comentario publicado en Barcelona. La Ciudad Condal, que su cuenta personal de Twitter, el in- ofrecía la Torre Agbar como sede y dependentista catalán asume que el apoyo de una de las más sólidas no ganar la sede de la EMA es, «sin agencias estatales del medicamento duda, una mala noticia», si bien re- como no pasó de primera ronda, lo calca que «ni Cataluña ni Barcelo- que puede calificarse de humillación. na son quienes han fallado». A su Culpar de este fiasco totalmente al juicio, es el Gobierno quien «no ha Gobierno central como ha hecho el estado a la altura» y recuerda que ya ex presidente de la Generalitat, el Ejecutivo del PP es el principal Carles Puigdemont o parcialmente responsable ante la UE. -

Julio Loras, Albert Fabà Aquellos Polvos Trajeron Estos Lodos. Diálogos Postelectorales Diciembre De 2019

Julio Loras, Albert Fabà Aquellos polvos trajeron estos lodos. Diálogos postelectorales Diciembre de 2019. La preocupación sobre el crecimiento de Vox dio lugar a un diálogo, a vuelapluma y poco sistemático, entre Julio Loras, biólogo y Alber Fabà, sociolingüista. Esas reflexiones se publicaron en Pensamiento crítico en su edición de enero. Ahora siguen dialogando, pero en este caso sobre el resultado de las últimas elecciones generales, la reacción en Catalunya a la sentencia del procés o la posibilidad de un gobierno de coalición que, en el momento en que se han redactado estas notas, aún no ha cuajado, a consecuencia de las dudas sobre la abstención (o no) de ERC en la investidura. ALBERT. Durante los últimos meses me acuerdo a menudo de Borgen, la serie de ficción en la cual tiene un notable protagonismo Kasper Juul, responsable de prensa de Birgitte Nyborg, primera ministra de Dinamarca. ¿Conoces la saga? JULIO. Hace mucho tiempo que no veo ni cine ni series. Llegaron a aburrirme. Por lo general, veía desde el principio por dónde iban a ir los tiros y perdían todo aliciente para mí. Aunque tengo algo de idea sobre esa serie por los medios. Creo que va de asesores de los políticos. ¿No es así? A. Exacto. Me viene al pelo, por eso del papel que parece que ha tenido Ivan Redondo en las decisiones que se han tomado en el PSOE, des de la moción de censura a Rajoy hasta ahora. Redondo es un típico asesor “profesional”. Que yo sepa, asesoró al candidato del PP en las municipales de Badalona en 2011. -

Palau De La Musica Catalana De Barcelona 36

Taula de contingut CITES 7 La Vanguardia - Catalán - 21/01/2018 "El ideal de justicia" con Javier del Pino, José Martí Gómez, José Mª Mena, José Mª Fernández Seijo y 8 Mateo Seguí que junto a Lourdes Lancho comentan la sentencia del Caso Palau que se dio a conocer .... Cadena Ser - A VIVIR QUE SON DOS DIAS - 21/01/2018 Ana Pastor, Javier Maroto, Juan Carlos Girauta, Carles Campuzano, Óscar Puente, Joan Tardá y Pablo 10 Echenique debaten sobre la corrupción política que afecta a partidos como el PP o CDC. LA SEXTA - EL OBJETIVO - 21/01/2018 Javier del Pino, Quique Peinado, Antonio Castelo y David Navarro comentan en clave de humor noticias 12 de la semana: caso Palau, trama Púnica, rama valenciana de la Gürtel, etc. Cadena Ser - A VIVIR QUE SON DOS DIAS - 20/01/2018 Entrevista a Mónica Oltra, vicepresidenta de la Generalitat Valenciana, para hablar de asuntos como los 13 recortes del gobierno, las pensiones, la corrupción en el PP y en la antigua Convergéncia o la .... LA SEXTA - LA SEXTA NOCHE - 20/01/2018 Iñaki López y los contertulios Ester Capella, Joan Mena, Maribel Martínez, Esperanza García, Lorena 16 Roldán y Carles Rivas debaten sobre la corrupción política, especialmente los casos juzgados esta .... LA SEXTA - LA SEXTA NOCHE - 20/01/2018 Iñaki López y los contertulios Ester Capella, Joan Mena, Maribel Martínez, Esperanza García, Lorena 19 Roldán y Carles Rivas debaten sobre el caso Palau de la Música y cómo afecta al PdeCAT, antigua .... LA SEXTA - LA SEXTA NOCHE - 20/01/2018 Iñaki López y el periodista Carlos Quílez analizan el caso de corrupción en Cataluña relacionado con el 21 caso Palau de la Música y cómo afecta al PdeCAT, antigua Convergència. -

Preses I Presos Bascos Al País Basc

Drets humans. Solucions. Pau. Preses i presos bascos al País Basc. Deixant enrere un conflicte que s’ha allargat massa, tant en temps com en patiment, al País Basc s’han obert noves oportunitats per construir un escenari de pau. Les converses i els acords adoptats entre diferents agents del País Basc, l’alto-el-foc d’ETA i la implicació i ajuda de la comunitat internacional, han obert el camí per solucionar el conflicte basc. Aquest ha deixat conseqüències de tot tipus i totes han de ser solucionades. Per avançar-hi, cal posar atenció també a la situació dels i les ciutadanes que a causa del conflicte estan empresonades o a l’exili, dispersats a centenars de quilometres del País Basc, amb el patiment afegit que suposa tant per a ells i elles com per als seus familiars. Com a primer pas, doncs, creiem que cal respectar els drets humans bàsics dels presos i preses basques. Respecte que comporta: · Traslladar al País Basc a tots el presos i preses bascos. · Alliberar els presos i preses amb malalties greus. · Acabar amb la prolongació de les condemnes i derogar les mesures que comporten la cadena perpètua. · Respectar tots els drets humans que els corresponen com a presos i com a persones. Per tal de reclamar als estats espanyol i francès que facin passos cap a una solució democràtica, les persones sotasignants subscrivim aquestes reivindicacions amb l’esperit d’impulsar-les des de Catalunya. I, alhora, donem suport a la mobilització del proper 12 de gener a Bilbao, convocada p e r Herrira -plataforma en defensa dels drets dels presos bascos-, amb l’adhesió d’un ampli suport social, així com de nombroses personalitats de la cultura, l’esport i la política basca. -

The Impact on Domestic Policy of the EU Code of Conduct on Arms Exports the Czech Republic, the Netherlands and Spain

The Impact on Domestic Policy of the EU Code of Conduct on Arms Exports The Czech Republic, the Netherlands and Spain SIPRI Policy Paper No. 21 Mark Bromley Stockholm International Peace Research Institute May 2008 © SIPRI, 2008 ISSN 1652-0432 (print) ISSN 1653-7548 (online) Printed in Sweden by CM Gruppen, Bromma Contents Contents iii Preface iv Abbreviations v 1. Introduction 1 2. EU engagement in arms export policies 5 The origins of the EU Code of Conduct 5 The development of the EU Code of Conduct since 1998 9 The impact on the framework of member states’ arms export policies 11 The impact on the process of member states’ arms export policies 12 The impact on the outcomes of member states’ arms export policies 13 Box 2.1. Non-EU multilateral efforts in the field of arms export policies 6 3. Case study: the Czech Republic 17 The Czech Republic’s engagement with the EU Code of Conduct 17 The impact on the framework of Czech arms export policy 19 The impact on the process of Czech arms export policy 21 The impact on the outcomes of Czech arms export policy 24 Box 3.1. Key Czech legislation on arms export controls 18 Table 3.1. Czech exports of military equipment, 1997–2006 24 4. Case study: the Netherlands 29 The Netherlands’ engagement with the EU Code of Conduct 29 The impact on the framework of Dutch arms export policy 31 The impact on the process of Dutch arms export policy 32 The impact on the outcomes of Dutch arms export policy 34 Box 4.1. -

Nous Lideratges En Moments De Canvi Reflexions Sobre Lideratge I Transformació Social Marc Parés Carola Castellà Joan Subirats (Coordinadors)

Nous lideratges en moments de canvi Reflexions sobre lideratge i transformació social Marc Parés Carola Castellà Joan Subirats (coordinadors) Informes breus #52 Nous lideratges en moments de canvi. Reflexions sobre lideratge i transformació social Marc Parés (coord.), Carola Castellà (coord.), Joan Subirats (coord.), Helena Cruz, Marc Grau-Solés i Gemma Sánchez Nous lideratges en moments de canvi Reflexions sobre lideratge i transformació social Marc Parés Carola Castellà Joan Subirats (coordinadors) Informes breus 52 EDUCACIÓ Informes breus és una col·lecció de la Marc Parés (coord.) és investigador de Fundació Jaume Bofill en què s’hi publiquen l’Institut de Govern i Polítiques Públiques els resums i les conclusions principals (UAB). d’investigacions i seminaris promoguts per la Fundació. També inclou alguns documents Carola Castellà (coord.) és investigadora de inèdits en llengua catalana. Les opinions l’Institut de Govern i Polítiques Públiques que s’hi expressen corresponen als autors. (UAB). Els Informes breus de la Fundació Jaume Bofill Joan Subirats (coord.) és investigador de estan disponibles per a descàrrega al web l’Institut de Govern i Polítiques Públiques www.fbofill.cat. (UAB). Primera edició: juliol de 2014 Helena Cruz és consultora a Sòcol Tecnolo- gia Social. © Fundació Jaume Bofill, 2014 Provença, 324 Marc Grau-Solés és consultor a Sòcol Tec- 08037 Barcelona nologia Social. [email protected] http://www.fbofill.cat Gemma Sánchez és consultora a Sòcol Tecnologia Social. Aquest treball està subjecte a la llicència Creative -

Compromesos Amb Les Persones!

15 i 16 març 2014 compromesos CENTRE DE amb les persones! CONVENCIONS convenció nacional INTERNACIONAL DE BARCELONA PROGRAMA DISSABTE 15 DE MARÇ MATÍ 09:30h Acreditacions 10:00h Benvinguda Pep Solé, Director de la Convenció Nacional Meritxell Borràs, Presidenta de la Comissió Nacional de Política Sectorial 10:15h ÀMBIT SOCIAL Presentació document Compromesos amb l’Estat del benestar Introducció: Carles Campuzano, Relator de la Convenció Nacional i Diputat de CiU al Congrés Presenten: Anna Figueras, Sectorial de Política Social i Família; Francesc Sancho, Sectorial de Sanitat; Jordi Roig, Sectorial d’Ensenyament Taula d’experts “Un país amb cohesió i justícia social” Rita Marzoa, Periodista; Enric Canet, Director de Relacions ciutadanes del Casal dels Infants - Acció social als barris; Salvador Busquets, Coordinador de les entitats socials de la Companyia de Jesús a Catalunya Moderadora: Esther Padró, Relatora de la Convenció Nacional i Directora del Servei de tutel·les de la Fundació Bellaterra Torn obert de paraules 11:30h a 12:00h Pausa 12:00h Intervencions: Josep Lluís Cleries, President de la Convenció Nacional Lluís Corominas, Vicesecretari general de Coordinació Institucional Josep Rull, Secretari d’Organització 12:30h ÀMBIT EUROPA Presentació document Compromesos amb Europa Introducció: Mireia Canals, Sectorial de Política Europea i Internacional Presenten: Marc Guerrero, Vicepresident de l’ALDE Party; Víctor Terradellas, Secretari de Relacions Internacionals de CDC Taula d’experts “Catalunya en una Europa millor” Martí Anglada, -

Garces-Mascarenas-Labour Migra WT-01.Indd

BURUH MIGRASI IMISCOE - MIGRACIŌN LABORAL State regulation of labour migration is confronted with a double paradox. First, RESEARCH while markets require a policy of open borders to ful l demands for migrant workers, the boundaries of citizenship impose some degree of closure to the outside. Second, BURUH MIGRASI while the exclusivity of citizenship requires closed membership, civil and human rights undermine the state’s capacity to exclude foreigners once they are in the country. MIGRACIŌN LABORAL By considering how Malaysia and Spain have responded to the demand for foreign labour, this book analyses what may be identi ed as the trilemma between markets, Labour Migration MIGRACIŌN LABORAL citizenship and rights. For though their markets are similar, the two countries have di erent approaches to citizenship and rights. We must thus ask: how do such Labour Migration in Malaysia and Spain MIGRACIŌN LABORAL divergences a ect state responses to market demands? How, in turn, do state regulations in Malaysia and Spain impact labour migration ows? And what does this mean for contemporary migration BURUH MIGRASI overall? Markets, Citizenship and Rights LABOUR MIGRATION Blanca Garcés-Mascareñas is a Juan de la Cierva postdoctoral researcher with the Interdisciplinary Research Group in Immigration (¥¦§¦) at Pompeu Fabra - BURUH MIGRASI University in Barcelona. MIGRACIŌN LABORAL “What does it mean to control immigration? at is the fundamental question posed in this intriguing comparative study, which breaks new theoretical ground. e Spanish and Malaysian states are caught on the horns of a familiar BURUH MIGRASI dilemma: how to satisfy the needs of the marketplace without compromising the social contract. -

Spain Moves Toward Military Rule in Catalonia

افغانستان آزاد – آزاد افغانستان AA-AA چو کشور نباشـد تن من مبـــــــاد بدین بوم وبر زنده یک تن مــــباد همه سر به سر تن به کشتن دهیم از آن به که کشور به دشمن دهیم www.afgazad.com [email protected] زبان های اروپائی European Languages http://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2017/10/12/spai-o12.html Spain moves toward military rule in Catalonia By Alex Lantier 12 October 2017 In a menacing speech to the Spanish Congress on Wednesday, Popular Party (PP) Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy stated that, in response to Catalan regional Premier Carles Puigdemont’s speech affirming the October 1 independence referendum, he was preparing to invoke Article 155 of the Spanish Constitution. This provision allows Madrid to suspend the authority of the Catalan regional government and seize control of the region’s finances and administration. With the Spanish media discussing the invocation of Article 116 to impose a state of emergency or state of siege, it is clear that Rajoy is moving rapidly to establish military rule not only in Catalonia, but across all of Spain. Army sources told El País Wednesday morning that they are preparing to move into Catalonia and crush any opposition from sections of the 17,000-strong Catalan regional police, the Mossos d'Esquadra, or civilians loyal to the Catalan nationalist parties. Under the attack plan, code- named Cota de Malla (Chain Mail), the army will back police and Guardia Civil operations in Catalonia. It will march significant forces into the region to support two units already there—a motorized infantry battalion in Barcelona and an armored battalion in Sant Climent Sescebes. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 ESADE Foundation GRI Tablesintheannexes

1 2015 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 ESADE Foundation ANNUAL REPORT ESADE FOUNDATION 2015-2016 This Report meets the guidelines of the Global Reporting Initiative. The inner margins of some pages contain references related to the GRI tables in the annexes. COVER GRI: G4 - 3 / 28 COVER CONTENTS 10 16 28 1. NEW DEVELOPMENTS 2. MISSION, VALUES 3. AcADEMIC AND KEY FACTS AND SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY UNITS 42 58 74 4. RESEARCH 5. OUTREACH 6. GLOBAL AND KNOWLEDGE AND SOCIAL DEBATE OUTLOOK 90 98 110 7. PEOPLE, 8. PRIVATE 9. GOVERNING INFRASTRUCTURE AND RESOURCES CONTRIBUTIONS BODIES 116 126 130 10. ESADE 11. ECONOMIC ANNEXES ALUMNI INFORMATION BUSINESS SCHOOL LAW SCHOOL FACULTY CAMPUS 2,459 1,104 1,103 85 66 77,287 m2 Students International Students International Other Total area students students 155 faculty members Faculty 28 BCN MAD Core Language 32,655 m2 BCN · Pedralbes 2,625 m2 Madrid campus instructors 42,007 m2 BCN · St. Cugat STAFF MEMBERS INCOME 364 50 €99 M People Internationals In gross income 1,190 in the Bachelor of Business Administration (BBA) 328 in the Bachelor in Law 217 in the Double Degree in Business Administration and Law 116 in the Bachelor in Global Governance 669 in the MSc Programmes in Management 217 in the Double Degree in Business Administration and Law 335 in the MBA 279 in the Master in Legal Practice 11 in the Master of Research 148 in master’s and postgraduate programes 37 in the PhD Programme 15 in the PhD Programme €11 M for ESADE Law School #5 €41 M for ESADE Business School EUROPEAN BUSINESS SCHOOL €35 M for Executive -

Leaders for Social Change

Ignasi Carreras, Amy Leaverton and Maria Sureda Leaders for social change Characteristics and competencies of leadership in NGOs Esade‐PwC Social Leadership Program 2008‐09 ESADE-PwC Social Leadership Program This publication forms part of the ESADE-PwC Social Leadership Pro- gram, organised by ESADE’s Institute for Social Innovation and the PricewaterhouseCoopers Foundation. It is a joint initiative aimed at gen- erating and spreading knowledge about leadership in NGOs and other non-profit organisations, as well as creating an area where social lead- ers can reflect and exchange experiences. The program’s objectives are: ► To generate knowledge on leadership in the NGO and non-profit or- ganisation sector. ► To help develop leadership capacities in Spanish non-profit organisa- tions. ► To spread the knowledge generated to all organisations in the sector. ► To help reinforce the credibility of the organisations in the third sector. In order to achieve this, the program combines the following elements: ► Leadership Forums: Working and exchange sessions with the manag- ers participating in the program ► Research ► The creation of case studies ► Annual publication with results ► Public engagements ► Regular diffusion. Ignasi Carreras, Amy Leaverton and Maria Sureda Leaders for social change Characteristics and competencies of leadership in NGOs Leaders for social change: Characteristics and competencies of leadership in NGOs Authors: Ignasi Carreras, Amy Leaverton and Maria Sureda With the collaboration of PricewaterhouseCoopers Foundation Revision and correction: Marita Osés Edition and Design: Institute for Social Innovation, ESADE, 2009 www.socialinnovation.esade.edu [email protected] Front and back cover images: © Ackley Road Photos - Fotolia.com ISBN: 978-84-88971-31-9 The contents of this document are the property of their authors and may not be used for com- mercial purposes.