The New Brunswick Railway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

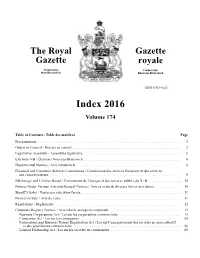

The Royal Gazette Index 2016

The Royal Gazette Gazette royale Fredericton Fredericton New Brunswick Nouveau-Brunswick ISSN 0703-8623 Index 2016 Volume 174 Table of Contents / Table des matières Page Proclamations . 2 Orders in Council / Décrets en conseil . 2 Legislative Assembly / Assemblée législative. 6 Elections NB / Élections Nouveau-Brunswick . 6 Departmental Notices / Avis ministériels. 6 Financial and Consumer Services Commission / Commission des services financiers et des services aux consommateurs . 9 NB Energy and Utilities Board / Commission de l’énergie et des services publics du N.-B. 10 Notices Under Various Acts and General Notices / Avis en vertu de diverses lois et avis divers . 10 Sheriff’s Sales / Ventes par exécution forcée. 11 Notices of Sale / Avis de vente . 11 Regulations / Règlements . 12 Corporate Registry Notices / Avis relatifs au registre corporatif . 13 Business Corporations Act / Loi sur les corporations commerciales . 13 Companies Act / Loi sur les compagnies . 54 Partnerships and Business Names Registration Act / Loi sur l’enregistrement des sociétés en nom collectif et des appellations commerciales . 56 Limited Partnership Act / Loi sur les sociétés en commandite . 89 2016 Index Proclamations Lagacé-Melanson, Micheline—OIC/DC 2016-243—p. 1295 (October 26 octobre) Acts / Lois Saulnier, Daniel—OIC/DC 2016-243—p. 1295 (October 26 octobre) Therrien, Michel—OIC/DC 2016-243—p. 1295 (October 26 octobre) Credit Unions Act, An Act to Amend the / Caisses populaires, Loi modifiant la Loi sur les—OIC/DC 2016-113—p. 837 (July 13 juillet) College of Physicians and Surgeons of New Brunswick / Collège des médecins Energy and Utilities Board Act / Commission de l’énergie et des services et chirurgiens du Nouveau-Brunswick publics, Loi sur la—OIC/DC 2016-48—p. -

Railroad Commissioners

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from scanned originals with text recognition applied (searchable text may contain some errors and/or omissions) Public Documents of iV1aine: BEING THE ANNUAL REPORTS OF THE VARIOUS Pu\Jlic Officers and Institutions FOR THE TEAR ~1886~ VOLUME II. AUGUSTA: SPRAGUE & SON, PRINTERS TO THE ST.ATE. 1886. REPORT OF THE Railroad Commissioners OF THE STATE OF MAINE. 1885. AUGUSTA: SPRAGUE & SON, PRINTERS TO THE STATE. 18 8 6. REPORT. To the Governor of the State of 11faine: Agreeably to the provisions of section 114 of chapter 51 of the Revjsed Statutes, we submit the Twenty-Seventh An nual Report of the Board of Railroad Commitisioncrs of the State, for the year ending December 1, 1885. While, by the laws of this State the Board of Commis sioners have not the general supervision of railroads and rail ways, as such hoards have in many of the other States, our powers and duties being more particularly defined, still, ·we deem it our privil<>ge and duty, as we have in the past, to make such suggestions and recommendations as we have thought may be beneficial to railroad managers and the public genernlly, basing it upon the theory that if any wrong;::; arn imffered by the puhlie, or any bene1ieial 1·esult:, may be ac complished, publieity would tend, to a great extent, to right such wrongs and stimulate managers of railroads to make such alterations and changes as might reasonably be expected to give more efficient service. -

2011 Volume 169

The Royal Gazette Gazette royale Fredericton Fredericton New Brunswick Nouveau-Brunswick ISSN 0703-8623 Index 2011 Volume 169 Table of Contents / Table des matières Page Proclamations . 2 Orders in Council / Décrets en conseil . 2 Legislative Assembly / Assemblée législative. 6 Elections NB / Élections Nouveau-Brunswick . 6 Departmental Notices / Avis ministériels . 6 NB Energy and Utilities Board / Commission de l’énergie et des services publics du N.-B. 10 New Brunswick Securities Commission / Commission des valeurs mobilières du Nouveau-Brunswick . 10 Notices Under Various Acts and General Notices / Avis en vertu de diverses lois et avis divers . 11 Sheriff’s Sales / Ventes par exécution forcée . 11 Notices of Sale / Avis de vente . 12 Regulations / Règlements . 14 Corporate Affairs Notices / Avis relatifs aux entreprises . 15 Business Corporations Act / Loi sur les corporations commerciales . 15 Companies Act / Loi sur les compagnies . 52 Partnerships and Business Names Registration Act / Loi sur l’enregistrement des sociétés en nom collectif et des appellations commerciales . 54 Limited Partnership Act / Loi sur les sociétés en commandite . 87 2011 Index Proclamations MacGregor, Scott R.—OIC/DC 2011-314—p. 1424 (November 16 novembre) Acts / Lois Pickett, James A.—OIC/DC 2011-204—p. 899 (August 3 août) Robichaud, Gérard—OIC/DC 2011-204—p. 899 (August 3 août) Auditor General Act, An Act to Amend the / Vérificateur général, Loi Stephen, Jason Andre—OIC/DC 2011-39—p. 283 (March 16 mars) modifiant la Loi sur le—OIC/DC 2011-245—p. 1052 (August 31 août) Sturgeon, Wayne—OIC/DC 2011-204—p. 899 (August 3 août) Credit Unions Act, An Act to Amend the / Caisses populaires, Loi modifiant Therrien, Roy—OIC/DC 2011-204—p. -

Secretary's Report from Chris Anstead

The Newsletter of the Canadian R.P.O. Study Group (B.N.A.P.S) Volume 32 - No. 4 Whole No. 171 March-April, 2004 In this issue, we study the postmarks used on the predecessor lines, which eventually formed the Cana- dian Pacific Railway in New Brunswick and an important connecting link to Quebec, the International Railway. Additionally, Bob Lane contributes some recollections of a former western R.P.O. clerk and Murray Smith and Jon Cable report new early and late dates. Congratulations to Peter McCarthy on receiving a Vermeil at Orapex in Ottawa for his exhibit, “Can- cellations used by Railroad Post Offices” and to Bob Lane on being awarded a Vermeil at the Edmonton National level show and a Gold at Orapex in Ottawa for his exhibit, “Railway Post Office Cancellations used in Manitoba”. Bob advises us that the BNAPS Manitoba and Northwestern Ontario Regional Group, and Brandon University, have agreed to produce the Jory Collection on the Internet. This collection of early Manitoba covers, which resides in the university’s archives and is rich in interesting RPO strikes. Secretary’s Report from Chris Anstead Two have joined our study group. Murray Smith 1092 TBRS, Bluewater Beach, RR # 1 Wyevale, ON, L0L 2T0 is a regular attendee of the BNAPEX meetings and a keen collector of Newfoundland postmarks. And Walter J. Veraart, Pr. Mauritsstraat 13, 1901 CL Castricum, The Netherlands, is our first Dutch member. His interests include R.P.O.s from coast to coast with a side interest in comic postcards with a R.P.O. -

Canadian Rail

Canadian Rail No. 431 NOVEMBER - DECEMBER 1992 CANADIAN RAIL ISSN 0008-4875 PUBLISHED BI-MONTHLY BY TH E CANADIAN RAILROAD HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION EDITOR: Fred F. Angus For your membership in the CRHA, which includes a CO-EDITOR: Douglas N. W_ Smith subscripliOfl 10 Canadian Rail. write 10: PRODUCTION: A. Stephen Walbridge CRHA. 120 Rue St-Pierre, Sf. Constant, Que. J5A 2G9 CARTOGRAPHER : William A. Germaniuk Rates: in Canada: $29 (including GST). lAYOUT: =-ed F, An gus outside Canada: $26 . in U.S. funds. I-' RINTING: Procel Printing TAB LE OF CO~ITENTS THE PHOENIX FOUNDRY AND GEORGE FLEMING (PART 2) ....... FRITZ LEHMANN .... .. .............. 183 THE RAILWAYS AND CANADA'S GREATEST DiSASTER .............. DOUGLAS N.W. SMITH ........... 201 5909'5 NEW YEAR'S EVE -- A ROUNDHOUSE FANTASy .. .............. NICHOLAS MORANT .............. 214 DRAWINGS OF CANADA'S RAILWAYS IN WORLD WAR 11. .. .......... THURSTAN TOPHAM ............. 215 RAIL CANADA DECISIONS ............. .... ....................... ....... .............. DOUGLAS N,W. SMITH ........... 216 Canadian Ra il is continually In need of news, stories, historical data. photos. maps and other material. Please send all coolributions to the editor: Fred F. Angus, 3021 Tratalgar Ave. Mootreat. P.O. H3Y 1H 3. No payment can be made for contributions. but the contrlbuter will begivencredit for material submined. Material will be returned to tllecontnbutori1 reQUested. Remember "Knowledge is ol linle value unless it is shared with others". NATIONAL DIRECTORS Frederick F. Angus Hugues W. Bonin J. Christopher Kyle Douglas N.w. S'nith Lawrence M. Unwlf: Jack A. Beatty Robert Carl son William Le Surt Charles De Jean Bernard Martin Richzrd Viberg Wal:cr J . Bedbrook Gerard t- 'echeue Roben V.V. -

PORT RISK CLASSIFICATION Dr

PORT RISK CLASSIFICATION Dr. Philip John, Fleet Manager, Coastal Shipping Ltd. Dr. James Christie, Professor, University of New Brunswick, and Dr. Michael Ircha, Association of Canadian Port Authorities Introduction Canada is a model for nations striving to achieve high standards of living and prosperity. It is vital that Canada take steps to demonstrate its continued commitment to economic progress in the marine sector, without compromising its respect for the environment and future generations. This is especially crucial in the current era of burgeoning maritime trade and the discovery and exploitation of new offshore oil and gas fields on the east coast. In 2010, the authors designed and successfully tested a port risk assessment procedure for port risk management.1 The procedure was applied to 21 ports on the east coast; five ports in each of the provinces of Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and one in Maine. These 21 ports were classified according to the level of risk pertaining to bringing a stricken oil tanker with hull damage into a place of refuge in the port. As prime examples at opposite ends of the risk spectrum, two ports are assessed for risk, one is a ‘Very High Risk’ port (the port of Miramichi) and the other a ‘Low Risk’ port (the port of Saint John). The findings of the port risk classification and the financial resources needed to upgrade the refuge suitability of the ports are presented in this paper. This risk classification has general applicability and can be extended to include all 369 Canadian ports or any port in the world. -

Captain S. S. Heller and the First Organized Danish Migration to Canada

The Bridge Volume 29 Number 1 Article 7 2006 Captain S. S. Heller and the First Organized Danish Migration to Canada Erik John Nielsen Lang Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/thebridge Part of the European History Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, and the Regional Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Lang, Erik John Nielsen (2006) "Captain S. S. Heller and the First Organized Danish Migration to Canada," The Bridge: Vol. 29 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/thebridge/vol29/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Bridge by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Captain S. S. Heller and the First Organized Danish Migration to Canada by Erik John Nielsen Lang The first, largest, and only organized migration of Danish settlers to Canada in the 19th century was directed to the settlement of New Denmark in the Canadian province of New Brunswick. The active recruitment of Danish migrants was a shift of focus for the provincial government, which had before relied almost exclusively on British settlers. Established in 1872, New Denmark's location placed it amongst the traditional ethnic groups of Victoria County: French-Canadian, English, Scottish, and Irish. Danes would not have chosen to migrate to the province at all had it not been for a Danish emigration promoter whose life, motivations, and intentions have remained understudied. The main stimulus for the Danish migration to New Brunswick resulted from a proposal put forth in 1871 by Captain S0ren Severin Heller and George Stymest to the provincial government. -

Maine State Legislature

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from scanned originals with text recognition applied (searchable text may contain some errors and/or omissions) Public Documents of Maine: BEING THE ANNUAL REPORTS OF THE VARIOUS Pu~lic Officers an~ Institutions FOR THE YEAR ~/ ~188, ~ VOLUME IL AUGUSTA: BURLEIGH & FLYNT, PRINTERS TO THE STAT.14;, 1889. REPORT OF THE Railroad Commissioners OF THE STATE OF nifA_INE. 1887. ---- ·------ AUGUSTA: BURLEIGH & FLYNT, PRINTERS TO THE S-TA'l!E~ 18 8 8. REPORT. To the Gove1·n01· of the State of iliaine: The Board of Railroad Commissioners respectfully submits this their twenty-ninth annual report. It is with a feeling of gratitude and pleasure that we can note the fact, that, while a series of appalling accidents have oc curred on many railroads in other States during the past year, the railroads in Maine have been comparatively free from ac cidents of any kind. This result, we believe, is very largely due to the wisdom, care and efficiency of those entrusted with the management of the several· railroads in the State, in the selection of subordinates and cmployes, and in looking care fully to the physical condition of their roads, and in the adop tion of and adhesion to modern systems of running trains thereon. The reports of the several railroad companies in the State show a most gratifying and, as appears, permanent increase in business both in passenger and freight earnings, notwith standing the fact that in the early part of the season many railroads on the seaboard were seriously effected by some of the provis10ns of the :ilnterstate Commerce Law," which pro visions, in effect, tended to divert freight traffic from railroads to steam and other vessels, at all competing points. -

A Short History of Carleton County New Brunswick

B E N P G R IF F IT H an o l E U T . , fficer r ’ iA D L n s cor s s aid to a in e a c ey p , h ve been the first per m an ent settler in the town — o r pa r is h of Wo o dstock From a n oil p a inting . C H A P T E R I . aking t o pla ce before the pu blic s ome impress i ons and facts of d nd a a a a a c ounty an , incidentally , o f Victor ia a M d w sk , my ide is o m a al to establish a guide post here and there , which , with the c pious tter n n o a re ady published , m ay a id s ome one in the future , with a incli ation to l c l o a f o o f A hist ry in the l arger t sk o editing a c omplete hist ry the c ounty . good d eal of l o cal tra dition ab out the upper S t . J ohn Valley c ountry i s worthy o f more permanent rec ord . l ve h ave le a rned th a t hi st ory t o b e ih r s in f n d an te e t g , consis ts not o nly of the d oings o kings a c ourtiers d s oldiers an d th e d escripti on of b attles , in m any c a ses , m ore bl oody th an gl o ri ous . -

Right of Way and Track Maps of the Bangor & Aroostook Railroad Co

Right of Way and Track Maps of the Bangor & Aroostook Railroad Co. MCC-00453 Finding Aid Prepared by Anne Chamberland, February 2019 Acadian Archives/Archives acadiennes University of Maine at Fort Kent Fort Kent, Maine Title: Right of Way and Track Maps of the Bangor & Aroostook Railroad Co. Creator/Collector: Collection number: MCC-00453 Shelf list number: K-453 (mobile map file) Dates: 1916 - 1927 Extent: 20 maps (0.94 cubic feet) Provenance: Material was acquired from Daniel ‘Danny’ Nicolas on May 1, 2018. Language: English Conservation notes: All maps were inserted in clear archival sleeves for protection and placed in individual blueprint storage tube. Access restrictions: None. Physical restrictions: None. Technical restrictions: None. Copyright: Copyright has not been assigned to the Acadian Archives/Archives acadiennes. All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Acadian Archives/Archives acadiennes Citation: Right of Way and Track Maps of the Bangor & Aroostook Railroad Co., MCC-00453, Acadian Archives/Archives acadiennes, University of Maine at Fort Kent Separated materials: 1870 Penobscot County Census on microfilm; 1850 Piscataquis County Census on microfilm; 1870 Androscoggin County Census on microfilm. Related materials: DVD HE2791 .B33 2004 Bangor & Aroostook Railroad [videorecording] : the first 100 years, 1891-1991. HE2791.B33 B36 1966 The Bangor and Aroostook, 1891-1966. MCC-00159 Bangor and Aroostook Railroad and connections map, circa 1910-1961. MCC-00333 Acadian Archives/Archives acadiennes collection on the Bangor and Aroostook Railroad in Fort Kent (Me.), 1975-2004. Location of originals: Not applicable. Location of copies: Not applicable. Published in: Not applicable. -

New Brunswick

Roster by location - New Brunswick Road Number Builder Serial Date Type Disposition Notes Austin Brook - Northern New Brunswick and Seaboard Austin Brook from the Drummond Mines at Austin Brook to the Intercolonial Railway, 1909 Northern New Brunswick and Seaboard 23 Unknown uu3338 2-8-0 DU [1p] Northern New Brunswick & Seaboard #23. Bathurst Bathurst Power and Paper 1 MLW 6646212 1925 2-6-0 Scr [np] Bathurst Power & Paper #1 (lettered Bathurst Company). 2 Porter uu2433 0-4-0T DU [1p] Bathurst Power & Paper #2. 3:1 GE 299375 1949 45T [n] Bathurst Power & Paper #3:1; [2p] Malagash Salt No#; [3] National Gypsum #3, Milford, 10/1959; [4] National Gypsum #3, Dartmouth. 3:2 MLW 7728112 1953 S-3 [n] Bathurst Power & Paper #3:2; [2p] Consolidated Bathurst #3; [3] Stone Consolidated #3, 1989. 5 Pittsburgh 7019 1883 4-6-0 Scr (np) Pittsburgh & Lake Erie #9196 (257, 163); (2) Atlantic Equipment (D), 4/1909; [3p] Willard Kitchen #1, 4/1909; [4] M.P. & J.T. Davis #4; [5] Bathurst Power & Paper #5; [6p] Stelco #10, 10/19/1918; [7] Canada Coal #4, 4/1945; Belledune Belledune Fertilizer 97 GE 3461110 1963 50T (n) General Aniline & Film #T120, Grasselli/Linden, NJ; [2] Belledune Fertilizer #97, 11/1973; [3] Brunswick Smelting & Fertilizer #97. Campbellton International Railway of New Brunswick 5 MLW 49469 1910 4-6-0 DU [n] International Railway of New Brunswick #5. Chipman Barnes Construction Manchester 7021 1875 4-4-0 DU [1] Barnes Construction (Norton to Chipman construction); [2] ICR #52; [3p] New Brunswick Coal & Railway #4. -

Maine Northern Railway Company— 3 the Transaction in Docket No

Federal Register / Vol. 76, No. 107 / Friday, June 3, 2011 / Notices 32265 aircraft passengers. Any such Advisory Committee (FAAC) notice.1 MNRC recognizes that, although submission must specify whether such Recommendation #22 the trackage rights agreement covers request is to block the aircraft 3. Update on FAA Response to Process some track in Canada, Board identification number prior to the FAA’s Improvement Working Group jurisdiction only extends to the U.S.- release of the data-feed, or to block the (PIWG) Recommendations Canada border at Van Buren, Me. aircraft identification number from 4. Review of the Retrospective This trackage rights transaction stems release by the Direct Subscribers. Regulatory Review Report from MMA’s attempt to abandon a Should a specific request not be made, 5. Issue Area Status Reports From connecting line in Northern Maine. The the FAA will block the identification Assistant Chairs Board granted an application to number prior to its release of the data- 6. Remarks From Other EXCOM abandon that line, which is feed. Members approximately 233 miles long, in a The FAA will contact each Direct Attendance is open to the interested decision served in December 2010.2 The Subscriber to execute a revised MOA, public but limited to the space 233 miles of line was then acquired by incorporating the modified section nine, available. The FAA will arrange the State of Maine, by and through its within 60 days of this Notice. teleconference service for individuals Department of Transportation (State), in Issued in Washington, DC, on May 27, wishing to join in by teleconference if January 2011.