Reportative Evidentiality, Attribution and Epistemic Modality: a Corpus-Based Diachronic Study of Latin Secundum NP (‘According to NP’)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Veridicality and Utterance Meaning

2011 Fifth IEEE International Conference on Semantic Computing Veridicality and utterance understanding Marie-Catherine de Marneffe, Christopher D. Manning and Christopher Potts Linguistics Department Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305 {mcdm,manning,cgpotts}@stanford.edu Abstract—Natural language understanding depends heavily on making the requisite inferences. The inherent uncertainty of assessing veridicality – whether the speaker intends to convey that pragmatic inference suggests to us that veridicality judgments events mentioned are actual, non-actual, or uncertain. However, are not always categorical, and thus are better modeled as this property is little used in relation and event extraction systems, and the work that has been done has generally assumed distributions. We therefore treat veridicality as a distribution- that it can be captured by lexical semantic properties. Here, prediction task. We trained a maximum entropy classifier on we show that context and world knowledge play a significant our annotations to assign event veridicality distributions. Our role in shaping veridicality. We extend the FactBank corpus, features include not only lexical items like hedges, modals, which contains semantically driven veridicality annotations, with and negations, but also structural features and approximations pragmatically informed ones. Our annotations are more complex than the lexical assumption predicts but systematic enough to of world knowledge. The resulting model yields insights into be included in computational work on textual understanding. the complex pragmatic factors that shape readers’ veridicality They also indicate that veridicality judgments are not always judgments. categorical, and should therefore be modeled as distributions. We build a classifier to automatically assign event veridicality II. CORPUS ANNOTATION distributions based on our new annotations. -

Measuring the Comprehension of Negation in 2- to 4-Year-Old Children Ann E

Measuring the comprehension of negation in 2- to 4-year-old children Ann E. Nordmeyer Michael C. Frank [email protected] [email protected] Department of Psychology Department of Psychology Stanford University Stanford University Abstract and inferential negation (i.e. negation of inferred beliefs of others). Regardless of taxonomy, negation is used in a variety Negation is one of the most important concepts in human lan- guage, and yet little is known about children’s ability to com- of contexts to express a range of different thoughts. prehend negative sentences. In this experiment, we explore The relationship between different types of negation is un- how children’s comprehension of negative sentences changes between 2- to 4-year-old children, as well as how comprehen- known. One possibility is that distinct categories of negation sion is influenced by how negative sentences are used. Chil- belong to a single cohesive concept. Even pre-linguistically, dren between the ages of 2 and 4 years watched a video in nonexistence, rejection, and denial could all fall under a su- which they heard positive and negative sentences. Negative sentences, such as “look at the boy with no apples”, referred perordinate conceptual category of negation. It is also pos- either to an absence of a characteristic or an alternative char- sible, however, that these types of negation represent fun- acteristic. Older children showed significant improvements in damentally different concepts. For example, the situation in speed and accuracy of looks to target. Children showed more rejection difficulty when the negative sentence referred to nothing, com- which a child expresses a dislike for going outside ( ) pared to when it referred to an alternative. -

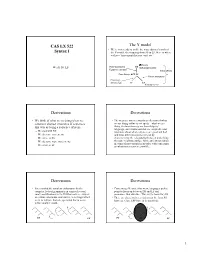

CAS LX 522 Syntax I the Y Model

CAS LX 522 The Y model • We’re now ready to tackle the most abstract branch of Syntax I the Y-model, the mapping from SS to LF. Here is where we have “movement that you can’t see”. θ Theory Week 10. LF Overt movement, DS Subcategorization Expletive insertion X-bar theory Case theory, EPP SS Covert movement Phonology/ Morphology PF LF Binding theory Derivations Derivations • We think of what we’re doing when we • The steps are not necessarily a reflection of what construct abstract structures of sentences we are doing online as we speak—what we are this way as being a sequence of steps. doing is characterizing our knowledge of language, and it turns out that we can predict our – We start with DS intuitions about what sentences are good and bad – We do some movements and what different sentences mean by – We arrive at SS characterizing the relationship between underlying – We do some more movements thematic relations, surface form, and interpretation in terms of movements in an order with constraints – We arrive at LF on what movements are possible. Derivations Derivations • It seems that the simplest explanation for the • Concerning SS, under this view, languages pick a complex facts of grammar is in terms of several point to focus on between DS and LF and small modifications to the DS that each are subject pronounce that structure. This is (the basis for) SS. to certain constraints, sometimes even things which • There are also certain restrictions on the form SS seem to indicate that one operation has to occur has (e.g., Case, EPP have to be satisfied). -

8. Binding Theory

THE COMPLICATED AND MURKY WORLD OF BINDING THEORY We’re about to get sucked into a black hole … 11-13 March Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 2 OUR ROADMAP •Overview of Basic Binding Theory •Binding and Infinitives •Some cross-linguistic comparisons: Icelandic, Ewe, and Logophors •Picture NPs •Binding and Movement: The Nixon Sentences 3 SOME TERMINOLOGY • R-expression: A DP that gets its meaning by referring to an entity in the world. • Anaphor: A DP that obligatorily gets its meaning from another DP in the sentence. 1. Heidi bopped herself on the head with a zucchini. [Carnie 2013: Ch. 5, EX 3] • Reflexives: Myself, Yourself, Herself, Himself, Itself, Ourselves, Yourselves, Themselves • Reciprocals: Each Other, One Another • Pronoun: A DP that may get its meaning from another DP in the sentence or contextually, from the discourse. 2. Art said that he played basketball. [EX5] • “He” could be Art or someone else. • I/Me, You/You, She/Her, He/Him, It/It, We/Us, You/You, They/Them • Nominative/Accusative Pronoun Pairs in English • Antecedent: A DP that gives its meaning to another DP. • This is familiar from control; PRO needs an antecedent. Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 4 OBSERVATION 1: NO NOMINATIVE FORMS OF ANAPHORS • This makes sense, since anaphors cannot be subjects of finite clauses. 1. * Sheselfi / Herselfi bopped Heidii on the head with a zucchini. • Anaphors can be the subjects of ECM clauses. 2. Heidi believes herself to be an excellent cook, even though she always bops herself on the head with zucchini. SOME DESCRIPTIVE OBSERVATIONS Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. -

Annotating Tense, Mood and Voice for English, French and German

Annotating tense, mood and voice for English, French and German Anita Ramm1;4 Sharid Loaiciga´ 2;3 Annemarie Friedrich4 Alexander Fraser4 1Institut fur¨ Maschinelle Sprachverarbeitung, Universitat¨ Stuttgart 2Departement´ de Linguistique, Universite´ de Geneve` 3Department of Linguistics and Philology, Uppsala University 4Centrum fur¨ Informations- und Sprachverarbeitung, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat¨ Munchen¨ [email protected] [email protected] fanne,[email protected] Abstract features. They may, for instance, be used to clas- sify texts with respect to the epoch or region in We present the first open-source tool for which they have been produced, or for assigning annotating morphosyntactic tense, mood texts to a specific author. Moreover, in cross- and voice for English, French and Ger- lingual research, tense, mood, and voice have been man verbal complexes. The annotation is used to model the translation of tense between based on a set of language-specific rules, different language pairs (Santos, 2004; Loaiciga´ which are applied on dependency trees et al., 2014; Ramm and Fraser, 2016)). Identi- and leverage information about lemmas, fying the morphosyntactic tense is also a neces- morphological properties and POS-tags of sary prerequisite for identifying the semantic tense the verbs. Our tool has an average accu- in synthetic languages such as English, French racy of about 76%. The tense, mood and or German (Reichart and Rappoport, 2010). The voice features are useful both as features extracted tense-mood-voice (TMV) features may in computational modeling and for corpus- also be useful for training models in computational linguistic research. linguistics, e.g., for modeling of temporal relations (Costa and Branco, 2012; UzZaman et al., 2013). -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

A Syntactic Analysis of Rhetorical Questions

A Syntactic Analysis of Rhetorical Questions Asier Alcázar 1. Introduction* A rhetorical question (RQ: 1b) is viewed as a pragmatic reading of a genuine question (GQ: 1a). (1) a. Who helped John? [Mary, Peter, his mother, his brother, a neighbor, the police…] b. Who helped John? [Speaker follows up: “Well, me, of course…who else?”] Rohde (2006) and Caponigro & Sprouse (2007) view RQs as interrogatives biased in their answer set (1a = unbiased interrogative; 1b = biased interrogative). In unbiased interrogatives, the probability distribution of the answers is even.1 The answer in RQs is biased because it belongs in the Common Ground (CG, Stalnaker 1978), a set of mutual or common beliefs shared by speaker and addressee. The difference between RQs and GQs is thus pragmatic. Let us refer to these approaches as Option A. Sadock (1971, 1974) and Han (2002), by contrast, analyze RQs as no longer interrogative, but rather as assertions of opposite polarity (2a = 2b). Accordingly, RQs are not defined in terms of the properties of their answer set. The CG is not invoked. Let us call these analyses Option B. (2) a. Speaker says: “I did not lie.” b. Speaker says: “Did I lie?” [Speaker follows up: “No! I didn’t!”] For Han (2002: 222) RQs point to a pragmatic interface: “The representation at this level is not LF, which is the output of syntax, but more abstract than that. It is the output of further post-LF derivation via interaction with at least a sub part of the interpretational component, namely pragmatics.” RQs are not seen as syntactic objects, but rather as a post-syntactic interface phenomenon. -

Minimal Pronouns1

1 Minimal Pronouns1 Fake Indexicals as Windows into the Properties of Bound Variable Pronouns Angelika Kratzer University of Massachusetts at Amherst June 2006 Abstract The paper challenges the widely accepted belief that the relation between a bound variable pronoun and its antecedent is not necessarily submitted to locality constraints. It argues that the locality constraints for bound variable pronouns that are not explicitly marked as such are often hard to detect because of (a) alternative strategies that produce the illusion of true bound variable interpretations and (b) language specific spell-out noise that obscures the presence of agreement chains. To identify and control for those interfering factors, the paper focuses on ‘fake indexicals’, 1st or 2nd person pronouns with bound variable interpretations. Following up on Kratzer (1998), I argue that (non-logophoric) fake indexicals are born with an incomplete set of features and acquire the remaining features via chains of local agreement relations established in the syntax. If fake indexicals are born with an incomplete set of features, we need a principled account of what those features are. The paper derives such an account from a semantic theory of pronominal features that is in line with contemporary typological work on possible pronominal paradigms. Keywords: agreement, bound variable pronouns, fake indexicals, meaning of pronominal features, pronominal ambiguity, typologogy of pronouns. 1 . I received much appreciated feedback from audiences in Paris (CSSP, September 2005), at UC Santa Cruz (November 2005), the University of Saarbrücken (workshop on DPs and QPs, December 2005), the University of Tokyo (SALT XIII, March 2006), and the University of Tromsø (workshop on decomposition, May 2006). -

The Syntax of Answers to Negative Yes/No-Questions in English Anders Holmberg Newcastle University

The syntax of answers to negative yes/no-questions in English Anders Holmberg Newcastle University 1. Introduction This paper will argue that answers to polar questions or yes/no-questions (YNQs) in English are elliptical expressions with basically the structure (1), where IP is identical to the LF of the IP of the question, containing a polarity variable with two possible values, affirmative or negative, which is assigned a value by the focused polarity expression. (1) yes/no Foc [IP ...x... ] The crucial data come from answers to negative questions. English turns out to have a fairly complicated system, with variation depending on which negation is used. The meaning of the answer yes in (2) is straightforward, affirming that John is coming. (2) Q(uestion): Isn’t John coming, too? A(nswer): Yes. (‘John is coming.’) In (3) (for speakers who accept this question as well formed), 1 the meaning of yes alone is indeterminate, and it is therefore not a felicitous answer in this context. The longer version is fine, affirming that John is coming. (3) Q: Isn’t John coming, either? A: a. #Yes. b. Yes, he is. In (4), there is variation regarding the interpretation of yes. Depending on the context it can be a confirmation of the negation in the question, meaning ‘John is not coming’. In other contexts it will be an infelicitous answer, as in (3). (4) Q: Is John not coming? A: a. Yes. (‘John is not coming.’) b. #Yes. In all three cases the (bare) answer no is unambiguous, meaning that John is not coming. -

Tenses and Conjugation (Pdf)

Created by the Evergreen Writing Center Library 3407 867-6420 Tenses and Conjugation Using correct verb forms is crucial to communicating coherently. Understanding how to apply different tenses and properly conjugate verbs will give you the tools with which to craft clear, effective sentences. Conjugations A conjugation is a list of verb forms. It catalogues the person, number, tense, voice, and mood of a verb. Knowing how to conjugate verbs correctly will help you match verbs with their subjects, and give you a firmer grasp on how verbs function in different sentences. Here is a sample conjugation table: Present Tense, Active Voice, Indicative Mood: Jump Person Singular Plural 1st Person I jump we jump 2nd Person you jump you jump 3rd Person he/she/it jumps they jump Person: Person is divided into three categories (first, second, and third person), and tells the reader whether the subject is speaking, is spoken to, or is spoken about. Each person is expressed using different subjects: first person uses I or we; second person uses you; and third person uses he/she/it or they. Keep in mind that these words are not the only indicators of person; for example in the sentence “Shakespeare uses images of the divine in his sonnets to represent his own delusions of grandeur”, the verb uses is in the third person because Shakespeare could be replaced by he, an indicator of the third person. Number: Number refers to whether the verb is singular or plural. Tense: Tense tells the reader when the action of a verb takes place. -

Double Classifiers in Navajo Verbs *

Double Classifiers in Navajo Verbs * Lauren Pronger Class of 2018 1 Introduction Navajo verbs contain a morpheme known as a “classifier”. The exact functions of these morphemes are not fully understood, although there are some hypotheses, listed in Sec- tions 2.1-2.3 and 4. While the l and ł-classifiers are thought to have an effect on averb’s transitivity, there does not seem to be a comparable function of the ; and d-classifiers. However, some sources do suggest that the d-classifier is associated with the middle voice (see Section 4). In addition to any hypothesized semantic functions, the d-classifier is also one of the two most common morphemes that trigger what is known as the d-effect, essentially a voicing alternation of the following consonant explained in Section 3 (the other mor- pheme is the 1st person dual plural marker ‘-iid-’). When the d-effect occurs, the ‘d’ of the involved morpheme is often realized as null in the surface verb. This means that the only evidence of most d-classifiers in a surface verb is the voicing alternation of the following stem-initial consonant from the d-effect. There is also a rare phenomenon where two *I would like to thank Jonathan Washington and Emily Gasser for providing helpful feedback on earlier versions of this thesis, and Jeremy Fahringer for his assistance in using the Swarthmore online Navajo dictionary. I would also like to thank Ted Fernald, Ellavina Perkins, and Irene Silentman for introducing me to the Navajo language. 1 classifiers occur in a single verb, something that shouldn’t be possible with position class morphology. -

Binding Theory

HG4041 Theories of Grammar Binding Theory Francis Bond Division of Linguistics and Multilingual Studies http://www3.ntu.edu.sg/home/fcbond/ [email protected] Lecture 5 Location: HSS SR3 HG4041 (2013) Overview ➣ What we are trying to do ➣ Last week: Semantics ➣ Review of Chapter 1’s informal binding theory ➣ What we already have that’s useful ➣ What we add in Ch 7 (ARG-ST, ARP) ➣ Formalized Binding Theory ➣ Binding and PPs ➣ Imperatives Sag, Wasow and Bender (2003) — Chapter 7 1 What We’re Trying To Do ➣ Objectives ➢ Develop a theory of knowledge of language ➢ Represent linguistic information explicitly enough to distinguish well- formed from ill-formed expressions ➢ Be parsimonious, capturing linguistically significant generalizations. ➣ Why Formalize? ➢ To formulate testable predictions ➢ To check for consistency ➢ To make it possible to get a computer to do it for us Binding Theory 2 How We Construct Sentences ➣ The Components of Our Grammar ➢ Grammar rules ➢ Lexical entries ➢ Principles ➢ Type hierarchy (very preliminary, so far) ➢ Initial symbol (S, for now) ➣ We combine constraints from these components. ➣ More in hpsg.stanford.edu/book/slides/Ch6a.pdf, hpsg.stanford.edu/book/slides/Ch6b.pdf Binding Theory 3 Review of Semantics Binding Theory 4 Overview ➣ Which aspects of semantics we’ll tackle ➣ Semantics Principles ➣ Building semantics of phrases ➣ Modification, coordination ➣ Structural ambiguity Binding Theory 5 Our Slice of a World of Meanings Aspects of meaning we won’t account for (in this course) ➣ Pragmatics ➣ Fine-grained lexical semantics The meaning of life is ➢ life or life′ or RELN life "INST i # ➢ Not like wordnet: life1 ⊂ being1 ⊂ state1 . ➣ Quantification (covered lightly in the book) ➣ Tense, Mood, Aspect (covered in the book) Binding Theory 6 Our Slice of a World of Meanings MODE prop INDEX s RELN save RELN name RELN name SIT s RESTR , NAME Chris , NAME Pat * SAVER i + NAMED i NAMED j SAVED j “.