Sequence and Salience in Namia Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PAPERS in NEW GUINEA LINGUISTICS No. 18

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS S e.ft-<- e..6 A - No. 4 0 PAPERS IN NEW GUINEA LINGUISTICS No. 18 by R. Conrad and W. Dye N.P. Thomson L.P. Bruce, Jr. Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Conrad, R., Dye, W., Thomson, N. and Bruce Jr., L. editors. Papers in New Guinea Linguistics No. 18. A-40, iv + 106 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1975. DOI:10.15144/PL-A40.cover ©1975 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS is published by the Ling ui��ic Ci�cl e 06 Canbe��a and consists of four series: SERIES A - OCCAS IONAL PAPERS SERIES B - MONOGRAPHS SERIES C - BOOKS SERIES V - SPECIAL PUBLICATIONS . EDITOR: S.A. Wurm . ASSOCIATE EDITORS: D.C. Laycock , C.L. Voorhoeve . ALL CORRESPONDENCE concerning PACIFIC LINGUISTICS, including orders and subscriptions, should be addressed to: The Secretary, PACIFIC LINGUISTICS, Department of Linguistics, School of Pacific Studies, The Australian National University, Canberra , A.C.T. 2600. Australia . Copyright � The Authors. First published 1975 . The editors are indebted to the Australian National University for help in the production of this series. This publication was made possible by an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund. National Library of Australia Card Number and ISBN 0 85883 118 X TABLE OF CONTENTS Page SOME LANGUAGE RELATIONSHIPS IN THE UPPER SEPIK REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA, by Robert Conrad and Wayne Dye 1 O. INTRODUCTION 1 1 . -

Papers on Six Languages of Papua New Guinea

Papers on six languages of Papua New Guinea Pacific Linguistics 616 Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in grammars and linguistic descriptions, dictionaries and other materials on languages of the Pacific, Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, East Timor, southeast and south Asia, and Australia. Pacific Linguistics, established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund, is associated with the School of Culture, History and Language in the College of Asia and the Pacific at The Australian National University. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Publications are refereed by scholars with relevant expertise, who are usually not members of the editorial board. FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: I Wayan Arka and Malcolm Ross (Managing Editors), Mark Donohue, Nicholas Evans, David Nash, Andrew Pawley, Paul Sidwell, Jane Simpson, and Darrell Tryon EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD: Karen Adams, Arizona State University Marian Klamer, Universiteit Leiden Alexander Adelaar, University of Melbourne Harold Koch, The Australian National Peter Austin, School of Oriental and African University Studies Frantisek Lichtenberk, University of Byron Bender, University of Hawai‘i Auckland Walter Bisang, Johannes Gutenberg- John Lynch, University of the South Pacific Universität Mainz Patrick McConvell, Australian Institute of Robert Blust, University of Hawai‘i Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander David Bradley, La Trobe University Studies Lyle Campbell, University of Utah William McGregor, Aarhus Universitet James Collins, Universiti Kebangsaan Ulrike Mosel, Christian-Albrechts- Malaysia Universität zu Kiel Bernard Comrie, Max Planck Institute for Claire Moyse-Faurie, Centre National de la Evolutionary Anthropology Recherche Scientifique Matthew Dryer, State University of New York Bernd Nothofer, Johann Wolfgang Goethe- at Buffalo Universität Frankfurt am Main Jerold A. -

Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands

Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands First compiled by Nancy Sack and Gwen Sinclair Updated by Nancy Sack Current to January 2020 Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands Background An inquiry from a librarian in Micronesia about how to identify subject headings for the Pacific islands highlighted the need for a list of authorized Library of Congress subject headings that are uniquely relevant to the Pacific islands or that are important to the social, economic, or cultural life of the islands. We reasoned that compiling all of the existing subject headings would reveal the extent to which additional subjects may need to be established or updated and we wish to encourage librarians in the Pacific area to contribute new and changed subject headings through the Hawai‘i/Pacific subject headings funnel, coordinated at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.. We captured headings developed for the Pacific, including those for ethnic groups, World War II battles, languages, literatures, place names, traditional religions, etc. Headings for subjects important to the politics, economy, social life, and culture of the Pacific region, such as agricultural products and cultural sites, were also included. Scope Topics related to Australia, New Zealand, and Hawai‘i would predominate in our compilation had they been included. Accordingly, we focused on the Pacific islands in Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia (excluding Hawai‘i and New Zealand). Island groups in other parts of the Pacific were also excluded. References to broader or related terms having no connection with the Pacific were not included. Overview This compilation is modeled on similar publications such as Music Subject Headings: Compiled from Library of Congress Subject Headings and Library of Congress Subject Headings in Jewish Studies. -

Languages of the Upper Sepik and Central New Guinea

LANGUAGES OF THE UPPER SEPIK AND CENTRAL NEW GUINEA Report prepared by Martin Steer September 2005 Edits and Appendix 9.2 by B. Craig 2011 1 CONTENTS 1. Introduction 5 1.1 Overview 5 1.2 Methods of comparison 6 1.3 Structure of the report 9 2. Amto-Musian Family: Amto 10 3. Border Stock, Waris Family: Amanab and Waina 11 4. Kwomtari Stock: Baibai, Biaka and Kwomtari 15 5. Senagi Family: Anggor 18 6. Sepik Phylum 24 6.1 Abau 24 6.2 Yellow River Family: Ak, Awun, Namie 26 7. Trans New Guinea Phylum 28 7.1 The Mountain Ok family 28 7.2 The Mountain Ok languages 31 7.3 Lexical comparisons 34 7.4 Phonology and morphology 36 7.5 Discussion 38 7.6 Oksapmin 39 8. Isolates/Ungrouped 40 8.1 Busa 40 8.2 Yuri/Karkar 41 8.3 Nagatman/Yale 42 9. Appendices 44 9.1 Percentages of Cognates - Amanab sub-district and Upper Serpik 44 9.2 Data relating to Tifal and Faiwol language boundaries (by B.Craig) 45 10. Bibliography 53 2 List of Tables 1. Languages of the study area 5 2. Populkation of the study area 6 3. Relatedness of languages 8 4. A scale of relatedness 9 5. Codification of relationships 10 6. Amto 10 7. Amanab and Waina 11 8. Some Waris pronouns 12 9. Baibai, Biaka and Kwomtari 16 10. Some Kwomtari pronouns 17 11. Anggor 18 12. Dera versus languages to the north and west 20 13. pTNG and Dera 22 14. Anggor villages and dialects 23 15. -

Online Appendix To

Online Appendix to Hammarström, Harald & Sebastian Nordhoff. (2012) The languages of Melanesia: Quantifying the level of coverage. In Nicholas Evans & Marian Klamer (eds.), Melanesian Languages on the Edge of Asia: Challenges for the 21st Century (Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication 5), 13-34. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ’Are’are [alu] < Austronesian, Nuclear Austronesian, Malayo- Polynesian, Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian, Eastern Malayo- Polynesian, Oceanic, Southeast Solomonic, Longgu-Malaita- Makira, Malaita-Makira, Malaita, Southern Malaita Geerts, P. 1970. ’Are’are dictionary (Pacific Linguistics: Series C 14). Canberra: The Australian National University [dictionary 185 pp.] Ivens, W. G. 1931b. A Vocabulary of the Language of Marau Sound, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies VI. 963–1002 [grammar sketch] Tryon, Darrell T. & B. D. Hackman. 1983. Solomon Islands Languages: An Internal Classification (Pacific Linguistics: Series C 72). Canberra: Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University. Bibliography: p. 483-490 [overview, comparative, wordlist viii+490 pp.] ’Auhelawa [kud] < Austronesian, Nuclear Austronesian, Malayo- Polynesian, Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian, Eastern Malayo- Polynesian, Oceanic, Western Oceanic linkage, Papuan Tip linkage, Nuclear Papuan Tip linkage, Suauic unknown, A. (2004 [1983?]). Organised phonology data: Auhelawa language [kud] milne bay province http://www.sil.org/pacific/png/abstract.asp?id=49613 1 Lithgow, David. 1987. Language change and relationships in Tubetube and adjacent languages. In Donald C. Laycock & Werner Winter (eds.), A world of language: Papers presented to Professor S. A. Wurm on his 65th birthday (Pacific Linguistics: Series C 100), 393-410. Canberra: Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University [overview, comparative, wordlist] Lithgow, David. -

Steps Towards a Typology of Partial Agreement

Séminaire FieldLing Phonology Sebastian Fedden Université Paris 3/ LACITO 4 Sept 2018 Mianmin 2004 A brief CV • PhD with Nick Evans in Melbourne (2003-2007) • Research fellow at the MPI for Psycholinguistics with Steve Levinson (2007-2009) • Research fellow at the Surrey Morphology Group with Grev Corbett (2009-2014) • Assistant Professor at the University of Sydney with Nick Enfield (2015-2016) • Since 2016 Professor of Linguistics at Paris 3 Sorbonne Nouvelle / LACITO 2 My research - Papuan languages • A grammar of Mian (2011) • Synchronic and diachronic study of the structure of Mian and other Papuan languages • Tone • Gender • Ditransitives • Reciprocals • ‘Switch-reference’ • Grammaticalization • Trans New Guinea 3 My research - Typology • Nominal classification (gender and classifiers) • Corbett, Greville G., Sebastian Fedden and Raphael A. Finkel. 2017. Single versus concurrent feature systems: nominal classification in Mian. Linguistic Typology 21. 209-260. • Fedden, Sebastian & Greville G. Corbett. 2017. Gender and classifiers in concurrent systems: Refining the typology of nominal classification. Glossa: a journal of general linguistics 2(1). 34, 1-47. • Corbett, Greville G. & Sebastian Fedden. 2016. Canonical gender. Journal of Linguistics 52. 495-531. • Referential hierarchies and argument marking • using psycholinguistic experimentation (specially prepared video stimuli) 4 Overview • My research (New Guinea) • Segmental phonology • Tonal phonology 5 MY RESEARCH Séminaire FieldLing - Phonology 6 Google map New Guinea 7 Indigenous -

Introduction to the Namia Dictionary Becky Feldpausch, SIL PNG 2011

Introduction to the Namia Dictionary Becky Feldpausch, SIL PNG 2011 The Namia language community The 7000 speakers of Namia live in the northwest part of Papua New Guinea. The area they live in is swamp and grass-covered plains located north of the Sepik River in the Lumi Sub-District of Sandaun Province, although some Namia people also live south of the river in East Sepik Province. The language area extends from the Sand River on the west to approximately 15 kilometres east of the Yellow River, and from just south of the Sepik River north to near Kweifteim and the southern border of the Pouye language area. It has the largest population of any of the surrounding languages (Pouye, Awun, Amal, Ama, Abau, Yale, Kwomtari, Guriaso; see map 1). There are no road links between the provincial capital (Vanimo) and other district headquarters. Travel from the coast (usually from Aitape) has traditionally been on foot, and from the south people come by canoe upstream on the Sepik River from Ambunti or Pagwi. However, starting around the year 2000 timber and mining companies have begun work to the north of the Namia area, and they have established roads that give easier access going north and east. Traditionally, the staple diet of the Namia people is sago, supplemented by hunting and fishing and some gardening. The people inhabit an area of approximately 1200 square kilometres. There are 21 villages each with populations of 50-300 people, and one government station (see map 2) in the 5 social division areas listed below: The northwest area of -

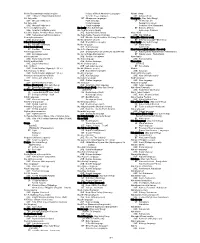

LCSH Section N

N-(3-trifluoromethylphenyl)piperazine Indians of North America—Languages Na'ami sheep USE Trifluoromethylphenylpiperazine West (U.S.)—Languages USE Awassi sheep N-3 fatty acids NT Athapascan languages Naamyam (May Subd Geog) USE Omega-3 fatty acids Eyak language UF Di shui nan yin N-6 fatty acids Haida language Guangdong nan yin USE Omega-6 fatty acids Tlingit language Southern tone (Naamyam) N.113 (Jet fighter plane) Na family (Not Subd Geog) BT Ballads, Chinese USE Scimitar (Jet fighter plane) Na Guardis Island (Spain) Folk songs, Chinese N.A.M.A. (Native American Music Awards) USE Guardia Island (Spain) Naar, Wadi USE Native American Music Awards Na Hang Nature Reserve (Vietnam) USE Nār, Wādī an N-acetylhomotaurine USE Khu bảo tồn thiên nhiên Nà Hang (Vietnam) Naʻar (The Hebrew word) USE Acamprosate Na-hsi (Chinese people) BT Hebrew language—Etymology N Bar N Ranch (Mont.) USE Naxi (Chinese people) Naar family (Not Subd Geog) BT Ranches—Montana Na-hsi language UF Nahar family N Bar Ranch (Mont.) USE Naxi language Narr family BT Ranches—Montana Na Ih Es (Apache rite) Naardermeer (Netherlands : Reserve) N-benzylpiperazine USE Changing Woman Ceremony (Apache rite) UF Natuurgebied Naardermeer (Netherlands) USE Benzylpiperazine Na-ion rechargeable batteries BT Natural areas—Netherlands n-body problem USE Sodium ion batteries Naas family USE Many-body problem Na-Kara language USE Nassau family N-butyl methacrylate USE Nakara language Naassenes USE Butyl methacrylate Ná Kê (Asian people) [BT1437] N.C. 12 (N.C.) USE Lati (Asian people) BT Gnosticism USE North Carolina Highway 12 (N.C.) Na-khi (Chinese people) Nāatas N.C. -

Abau Grammar

Data Papers on Papua New Guinea Languages Volume 57 Abau Grammar Arnold (Arjen) Hugo Lock 2011 SIL-PNG Academic Publications Ukarumpa, Papua New Guinea Papers in the series Data Papers on Papua New Guinea Languages express the authors’ knowledge at the time of writing. They normally do not provide a comprehensive treatment of the topic and may contain analyses which will be modified at a later stage. However, given the large number of undescribed languages in Papua New Guinea, SIL-PNG feels that it is appropriate to make these research results available at this time. René van den Berg, Series Editor Copyright © 2011 SIL-PNG Papua New Guinea [email protected] Published 2011 Printed by SIL Printing Press Ukarumpa, Eastern Highlands Province Papua New Guinea ISBN 9980 0 3614 1 Table of Contents List of maps and tables .......................................................................... ix Abbreviations ........................................................................................ xi 1. Introduction .................................................................................... 1 1.1 Location and population .......................................................... 1 1.2 Language name ....................................................................... 2 1.3 Affiliation and earlier studies................................................... 2 1.4 Dialects ................................................................................... 3 1.5 Language use and bilingualism ............................................... -

LCSH Section N

N-(3-trifluoromethylphenyl)piperazine Na Guardis Island (Spain) Naassenes USE Trifluoromethylphenylpiperazine USE Guardia Island (Spain) [BT1437] N-3 fatty acids Na Hang Nature Reserve (Vietnam) BT Gnosticism USE Omega-3 fatty acids USE Khu bảo tồn thiên nhiên Nà Hang (Vietnam) Nāatas N-6 fatty acids Na-hsi (Chinese people) USE Navayats USE Omega-6 fatty acids USE Naxi (Chinese people) Naath (African people) N.113 (Jet fighter plane) Na-hsi language USE Nuer (African people) USE Scimitar (Jet fighter plane) USE Naxi language Naath language N.A.M.A. (Native American Music Awards) Na Ih Es (Apache rite) USE Nuer language USE Native American Music Awards USE Changing Woman Ceremony (Apache rite) Naaude language N-acetylhomotaurine Na-Kara language USE Ayiwo language USE Acamprosate USE Nakara language Nab River (Germany) N Bar N Ranch (Mont.) Na-khi (Chinese people) USE Naab River (Germany) BT Ranches—Montana USE Naxi (Chinese people) Nabā, Jabal (Jordan) N Bar Ranch (Mont.) Na-khi language USE Nebo, Mount (Jordan) BT Ranches—Montana USE Naxi language Naba Kalebar Festival N-benzylpiperazine Na language USE Naba Kalebar Yatra USE Benzylpiperazine USE Sara Kaba Náà language Naba Kalebar Yatra (May Subd Geog) n-body problem Na-len-dra-pa (Sect) (May Subd Geog) UF Naba Kalebar Festival USE Many-body problem [BQ7675] BT Fasts and feasts—Hinduism N-butyl methacrylate UF Na-lendra-pa (Sect) Naba language USE Butyl methacrylate Nalendrapa (Sect) USE Nabak language N-carboxy-aminoacid-anhydrides BT Buddhist sects Nabagraha (Hindu deity) (Not Subd Geog) USE Amino acid anhydrides Sa-skya-pa (Sect) [BL1225.N38-BL1225.N384] N-cars Na-lendra-pa (Sect) BT Hindu gods USE General Motors N-cars USE Na-len-dra-pa (Sect) Nabak language (May Subd Geog) N Class (Destroyers) (Not Subd Geog) Na Maighdeanacha (Northern Ireland) UF Naba language BT Destroyers (Warships) USE Maidens, The (Northern Ireland) Wain language N. -

Towards a Typology of Participles

Department of Modern Languages University of Helsinki Towards a typology of participles Ksenia Shagal ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XII (Main Building), on the 1st of April, 2017 at 10 o’clock. Helsinki 2017 ISBN 978-951-51-2957-4 (paperback) ISBN 978-951-51-2958-1 (PDF) Printed by Unigrafia Helsinki 2017 Abstract The dissertation is a typological study of participles based on the concept of participle specifically designed for cross-linguistic comparison. In a few words, participles are defined as non-finite verb forms that can be employed for adnominal modification, e.g. the form written in the book [written by my supervisor]. The study is based on the data from more than 100 genetically and geographically diverse languages possessing the relevant forms. The data for the research comes mainly from descriptive grammars, but first-hand materials from native speakers, including those collected in several field trips, are also of utmost importance. The main theoretical aim of the dissertation is to describe the diversity of verb forms and clausal structures involved in participial relativization in the world’s languages, as well as to examine the paradigms formed by participial forms. In different chapters of the dissertation, participles are examined with respect to several parameters, such as participial orientation, expression of temporal, aspectual and modal meanings, possibility of verbal and/or nominal agreement, encoding of arguments, and some others. Finally, all the parameters are considered together in the survey of participial systems. The findings reported in the dissertation are representative of a significant diversity in the morphology of participles, their syntactic behaviour and the oppositions they form in the system of the language. -

LCSH Section Y

Y-Bj dialects Yabakei (Japan) Yachats River (Or.) USE Yugambeh-Bundjalung dialects USE Yaba Valley (Japan) BT Rivers—Oregon Y-cars Yabarana Indians (May Subd Geog) Yachats River Valley (Or.) USE General Motors Y-cars UF Yaurana Indians UF Yachats Valley (Or.) Y chromosome BT Indians of South America—Venezuela BT Valleys—Oregon UF Chromosome Y Yabbie culture Yachats Valley (Or.) BT Sex chromosomes USE Yabby culture USE Yachats River Valley (Or.) — Abnormalities (May Subd Geog) Yabbies (May Subd Geog) Yachikadai Iseki (Haga-machi, Tochigi-ken, Japan) BT Sex chromosome abnormalities [QL444.M33 (Zoology)] USE Yachikadai Site (Haga-machi, Tochigi-ken, Y Fenai (Wales) BT Cherax Japan) USE Menai Strait (Wales) Yabby culture (May Subd Geog) Yachikadai Site (Haga-machi, Tochigi-ken, Japan) Y-G personality test [SH380.94.Y32] This heading is not valid for use as a geographic USE Yatabe-Guilford personality test UF Yabbie culture subdivision. Y.M.C.A. libraries Yabby farming UF Yachikadai Iseki (Haga-machi, Tochigi-ken, USE Young Men's Christian Association libraries BT Crayfish culture Japan) Y maze Yabby farming BT Japan—Antiquities BT Maze tests USE Yabby culture Yachinaka Tate Iseki (Hinai-machi, Japan) Y Mountain (Utah) YABC (Behavioral assessment) USE Yachinaka Tate Site (Hinai-machi, Japan) BT Mountains—Utah USE Young Adult Behavior Checklist Yachinaka Tate Site (Hinai-machi, Japan) Wasatch Range (Utah and Idaho) Yabe family (Not Subd Geog) This heading is not valid for use as a geographic subdivision. Y-particles Yabem (Papua New Guinean