Lambert Walcot Kadmos 4 Dunnu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burn Your Way to Success Studies in the Mesopotamian Ritual And

Burn your way to success Studies in the Mesopotamian Ritual and Incantation Series Šurpu by Francis James Michael Simons A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics, Ancient History and Archaeology School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham March 2017 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The ritual and incantation series Šurpu ‘Burning’ is one of the most important sources for understanding religious and magical practice in the ancient Near East. The purpose of the ritual was to rid a sufferer of a divine curse which had been inflicted due to personal misconduct. The series is composed chiefly of the text of the incantations recited during the ceremony. These are supplemented by brief ritual instructions as well as a ritual tablet which details the ceremony in full. This thesis offers a comprehensive and radical reconstruction of the entire text, demonstrating the existence of a large, and previously unsuspected, lacuna in the published version. In addition, a single tablet, tablet IX, from the ten which comprise the series is fully edited, with partitur transliteration, eclectic and normalised text, translation, and a detailed line by line commentary. -

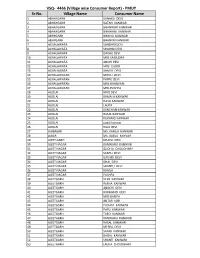

Sr No. Village Name Consumer Name VSQ- 4466 (Village Wise Consumer Report)

VSQ- 4466 (Village wise Consumer Report) - PMUY Sr No. Village Name Consumer Name 1 ABHAYGARH KANAKU DEVI 2 ABHAYGARH RATAN KANWAR 3 ABHAYGARH BHANWAR KANWAR 4 ABHAYGARH BHAWANI KANWAR 5 ABHYGARH BHIKHU KANWAR 6 ABHYGARH BHANVRI KANWAR 7 ACHALAWATA SUNDARI DEVI 8 ACHALAWATA SHOBHA DEVI 9 ACHALAWATA DAKHU DEVI 10 ACHALAWATA MRS SAMUDRA 11 ACHALAWATA ANOPI DEVI 12 ACHALAWATA MRS GUDDI 13 ACHALAWATA KAMLA DEVI 14 ACHALAWATAN MOOLI DEVI 15 ACHALAWATAN PAPPU DEVI 16 ACHALAWATAN MRS BHANVARI 17 ACHALAWATAN MRS PUSHPA 18 AGOLAI HIRO DEVI 19 AGOLAI KAMALA KANWAR 20 AGOLAI HAVA KANWAR 21 AGOLAI LALITA 22 AGOLAI KANCHAN KANWAR 23 AGOLAI RASAL KANWAR 24 AGOLAI RUKAMO KANWAR 25 AGOLAI guddi kanwar 26 AGOLAI RAJO DEVI 27 AJABASAR MS. KAMLA KANWAR 28 AJBAR MS. BABLU KANVAR 29 AJEET GARH DHAPU DEVI 30 AJEET NAGAR KANWARU KANWAR 31 AJEET NAGAR GUDIYA CHOUDHARY 32 AJEET NAGAR SANTU DEVI 33 AJEET NAGAR GAVARI DEVI 34 AJEET NAGAR DHAI DEVI 35 AJEET NAGAR SHANTU DEVI 36 AJEET NAGAR KAMLA . 37 AJEET NAGAR PUSHPA . 38 AJEETGARH VEER KANWAR 39 AJEETGARH REKHA KANWAR 40 AJEETGARH ANACHI DEVI 41 AJEETGARH RUKHAMO DEVI 42 AJEETGARH MRS BABITA 43 AJEETGARH ANTAR KOR 44 AJEETGARH PUSHPA KANWAR 45 AJEETGARH PAPU KANWAR 46 AJEETGARH TARO KANWAR 47 AJEETGARH KANWARU KANWAR 48 AJEETGARH RASAL KANWAR 49 AJEETGARH MEERA DEVI 50 AJEETGARH SAYAR KANWAR 51 AJEETGARH BADAL KANWAR 52 AJEETGARH SHANTI KANWAR 53 AJEETGARH LALITA CHOUDHARY Sr No. Village Name Consumer Name 54 AJEETGARH PEP KANWAR 55 AJEETGARH RASAL KANWAR 56 AJEETGARH JASU KANWAR 57 AJEETGARH LILA KANWAR 58 AJEETGARH KHAMMA DEVI 59 AJIT GADH SUGAN KANWAR 60 AJITGARH CHIMU DEVI 61 AJITGARH KANWARU KANWAR 62 AJJETGADH SOHNI DEVI 63 AKADEEYAWALA MAGEJ KANWAR 64 ALIDAS NAGAR PAPPU KANWAR 65 ALIDAS NAGAR PARVATI DEVI 66 ALIDAS NAGAR NAINU KANWAR 67 ALIDAS NAGAR MOHANI DEVI 68 ALIDAS NAGAR PISTA DEVI 69 ALIDAS NAGAR PRAKASH KANWAR 70 ALIDAS NAGAR NAKHTU DEVI 71 ALIDAS NAGAR DHAPU . -

Mesopotamian Culture

MESOPOTAMIAN CULTURE WORK DONE BY MANUEL D. N. 1ºA MESOPOTAMIAN GODS The Sumerians practiced a polytheistic religion , with anthropomorphic monotheistic and some gods representing forces or presences in the world , as he would later Greek civilization. In their beliefs state that the gods originally created humans so that they serve them servants , but when they were released too , because they thought they could become dominated by their large number . Many stories in Sumerian religion appear homologous to stories in other religions of the Middle East. For example , the biblical account of the creation of man , the culture of The Elamites , and the narrative of the flood and Noah's ark closely resembles the Assyrian stories. The Sumerian gods have distinctly similar representations in Akkadian , Canaanite religions and other cultures . Some of the stories and deities have their Greek parallels , such as the descent of Inanna to the underworld ( Irkalla ) resembles the story of Persephone. COSMOGONY Cosmogony Cosmology sumeria. The universe first appeared when Nammu , formless abyss was opened itself and in an act of self- procreation gave birth to An ( Anu ) ( sky god ) and Ki ( goddess of the Earth ), commonly referred to as Ninhursag . Binding of Anu (An) and Ki produced Enlil , Mr. Wind , who eventually became the leader of the gods. Then Enlil was banished from Dilmun (the home of the gods) because of the violation of Ninlil , of which he had a son , Sin ( moon god ) , also known as Nanna . No Ningal and gave birth to Inanna ( goddess of love and war ) and Utu or Shamash ( the sun god ) . -

Sibel Özbudun

Sibel Özbudun SİYASAL İKTİDARIN KURULMA VE KURUMSALLAŞMA SURECİNDE TÖRENLERİN İŞLEVLERİ 7H17IRC7IR K O P L 7 IR ARAŞTIRMA - İNCELEME DİZİSİ ANAHTAR KİTAPLAR YAYINEVİ Kloüfarer Cad. İletişim Han No:7 Kat:2 34400 Cağaloğlu-İstanbul Tel.: (0.212) 518 54 42 Fax: (0.212)638 11 12 SİBEL ÖZBUDUN AYİNDEN TÖRENE SİYASAL İKTİDARIN KURULMA VE KURUMSALLAŞMA SÜRECİNDE TÖRENLERİN İŞLEVLERİ AYİNDEN TÖRENE SİBEL ÖZBUDUN Kitabın Özgün Adı: Ayinden Törene Yayın Hakları: © Sibel Özbudun / Anahtar Kitaplar - 1997 Kapak Grafik: İrfan Ertel Kapak Resmi Tasarımlı Mustafa Deniz Arun Kapak Filmi: Ebru Grafik Baskı: Ceylan Matbaacılık Birinci Basım: Mart 1997 ISBN 975-7787-52-3 SİBEL ÖZBUDUN AYİNDEN • • TÖRENE SİYASAL İKTİDARIN KURULMA VE KURUMSALLAŞMA SÜRECİNDE TÖRENLERİN İŞLEVLERİ Geleceğin ‘töremiz’ toplumu için... S.Ö. İÇİNDEKİLER Önsöz........................................... .............................. 9 1. Bölüm: Kuramsal Çerçeve, Yöntem, Tanımlar, Yaklaşımlar........................................................ 11 1.1. Kuramsal Çerçeve.............................................................. 11 1.2. Yöntem................................................ *........ .................. 13 1.3. Tanımlar........................................................................... 16 1.4. Yaklaşımlar....................................................................... 21 1.4.1. Antropolojide Başlıca Yaklaşımlar............................. 21 1.4.2. Mitos ve Ayin Hareketi............................................. 24 1.4.3. Son Dönem Yaklaşımları......................................... -

The Mesopotamians Hungered for What? Literature, Material Culture, and Other Histories

Recebido: December 28, 2017│ Accepted: January 12, 2018 THE MESOPOTAMIANS HUNGERED FOR WHAT? LITERATURE, MATERIAL CULTURE, AND OTHER HISTORIES Kátia Maria Paim Pozzer1 Abstract The analyzes of the symbolic meaning of food, the culinary habits and the behavior at the table were stimulated by the New Cultural History and favored the studies on the relations between food, culture and social structure. Thus, in this article we intend to discuss the Mesopotamian banquet, its sacred roots, the myths of food creation, the material culture and the rich iconography on the subject. Keywords Mesopotamia; food; material culture; literature. Resumo As análises sobre a significação simbólica dos alimentos, os hábitos culinários e o comportamento à mesa foram impulsionadas pela Nova História Cultural e favoreceram os estudos sobre as relações entre alimentação, cultura e estrutura social. Assim, neste artigo pretendemos discutir o banquete mesopotâmico, suas raízes sagradas, os mitos de criação dos alimentos, a cultura material e a rica iconografia existente sobre o tema. Palavras-chave Mesopotâmia; alimentação; cultura material; literatura. 1 Assistant Professor, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil. E- mail: [email protected] Heródoto, Unifesp, Guarulhos, v. 2, n. 2, Dezembro, 2017. p. 153-167 - 153 - Participate in an academic homage to Prof. Pedro Paulo de Abreu Funari is a privilege because it means that at some point in my professional life I met Pedro Paulo (as he is affectionately called) and I was able to share his wisdom and generosity. Undoubtedly, Prof. Funari is one of the Brazilian exponents of History and Archeology, with greater insertion and international recognition. -

Mythsandlegends 11

하얀파도의 神話想像世界 11 - 메소포타미아 2010 신화ㆍ상상세계 사전 (神話ㆍ想像世界 辭典) 제11권 메소포타미아 일러두기 이 글을 제가 여기저기의 글을 편집해서 만든 신화ㆍ상상세계 사전의 열한 번째 부분이다. 티그리스와 유프라테스 강 사이에 있는 메소포타미아의 신화와 전설을 모 았다. 아직까지 Encyclopedia Mythica와 조철수의 『수메스 신화』에서 발췌한 내 용이 대부분이다. 하지만 조철수 교수는 세계에서 수메르어를 전공한 몇 안되는 분 중 한 분이기 때문에 앞으로 영어로 표기된 발음이 아니고 수메르어에 가까운 표기 로 수메르 신화를 접할 수 있을 것 같다. [ ] 안에 지역을 집어넣어 구별할 수 있도록 하였습니다. 책이름은 『 』에 넣 고, 잡지나 신문 등 기타는 「 」에 넣었다. (2008.8) 수메르 사람들은 기원전 4천경에 물건을 상징하는 물표를 만들어 그 표면에 물건 의 특색을 그려 넣어서 사용했다. 기원전 3300년경에 상형문자와 숫자를 쓰기 시작 했다. 그들은 중국 사람들처럼 많은 상형문자를 만들지 않았다. 기원전 2600년경에 는 사용하는 문자가 줄어들어 약 700개의 문자만 썼다. 수메르 사람들은 기존의 문 자를 조합해서 새로운 낱말로 만들어 썼다. 중국 사람들도 기존의 글자를 이용해서 새로운 뜻을 표현했지만, 그들은 새로운 글자를 만들어 냄으로써 글자 수가 기하급 수적으로 늘어나게 만들었다. 수메르 사람들은 “루(lu2, 사람)”와 “갈(gal, 큰)”을 합쳐서 갈루(GAL.LU2)로 표기 하고 루갈로 읽었다. 그 뜻은 “왕”이 되었다. 하지만 “큰 사람”을 말하는 경우에는 루-갈(lu2-gal)로 표기했다. 한편 한 문자를 여러 음으로 발음하고 그 뜻도 각기 다 른 경우가 있다. “입”은 카(ka)인데, “말하다”라는 뜻인 “둑(dug4)”으로 읽거나 “말 씀”이라는 뜻인 “이님(inim)”, “이빨”이라는 뜻인 “주(zu)”로 읽기도 했다. 수메르 사람들은 모든 단어를 표의문자로 만들지 않았다. “꿈”이라는 단어는 “마 무드(mamud)”라고 하는데, “꿈”이라는 표의문자를 만들지 않고 2개 음절로 “마-무 드(ma-mud)”로 표기했다. -

Ledgers and Prices: Early Mesopotamian Merchant Accounts

Ledgers and Prices Larly Mesopotamian Merchant Accounts 1)ANIl:l. C. SNEI-L \ew Haven and London Yale University Press Yale Near Eastern Researches, 8 EDlTORlA L COMMITTEE \VILL.IAM W HAL-LO. ed~tor MARVlh H. POPE WILLIAM K. SIMPSON Published with assistance from the In memory of Yale Babylonian Collection Iva Hawkins Snell and Clair John Snell Copyright @ 1982 by Yale University. All rights reser~ed. my first and best teachers This book may not be reproduced. in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the C.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press). without written permission from the publishers. Designed b! Sali! Harm and set In Timez Roman t!pe. Printed in the l'nited State\ of America b! The \'ail-Ballou Press. Bingharnton. S.Y. Librar~of Congress Cataloging In Publ~cationData Snell. Daniel C Ledgers and prices-earl! Mesopotamian merchant accounts (Yale Sear Eastern researches: 8) A re\ision of the author's thesis. Yale. 1975. Bihl~ograph!: p. Includes ~ndcx. I. Bookkeeping-~Histor! 2. .Accounting-~lraq History. 3. ?rlerchnnts - Iraq- hist to^-!. I. Title. 11. Series. HF5616.172S63 1982 657'.0935 80-26604 ISBh 0-300-025 17-3 Contents Tables ix Plates xi Acknowledgments xiii Abbreviations xv Metrological Tables xix Introduction i Study of Merchants 3 Study of Prices 6 1 The Forms of the Silver Accounts 11 Accounts Here Studied 12 A Representative Text 17 Parts of the Accounts 24 Toward a Definition 36 Distinctions .Among Accounts 40 Composition and Point of \'iew 45 -

Dictionary of Gods and Goddesses.Pdf

denisbul denisbul dictionary of GODS AND GODDESSES second edition denisbulmichael jordan For Beatrice Elizabeth Jordan Dictionary of Gods and Goddesses, Second Edition Copyright © 2004, 1993 by Michael Jordan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data denisbulJordan, Michael, 1941– Dictionary of gods and godesses / Michael Jordan.– 2nd ed. p. cm. Rev. ed. of: Encyclopedia of gods. c1993. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-5923-3 1. Gods–Dictionaries. 2. Goddesses–Dictionaries. I. Jordan, Michael, 1941– Encyclopedia of gods. II. Title. BL473.J67 2004 202'.11'03–dc22 2004013028 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by David Strelecky Cover design by Cathy Rincon Printed in the United States of America VBFOF10987654321 This book is printed on acid-free paper. CONTENTS 6 PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION v INTRODUCTION TO THE FIRST EDITION vii CHRONOLOGY OF THE PRINCIPAL RELIGIONS AND CULTURES COVERED IN THIS BOOK xiii DICTIONARY OF GODS AND GODDESSES denisbul1 BIBLIOGRAPHY 361 INDEX 367 denisbul PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION 6 It is explained in the introduction to this volume and the Maori. -

Divine Mediation and the Rise of Civilization in Mesopotamian Literature and in Genesis 1–11

The Journal of Hebrew Scriptures ISSN 1203-1542 http://www.jhsonline.org and http://purl.org/jhs Articles in JHS are being indexed in the ATLA Religion Database, RAMBI, and BiBIL. Their abstracts appear in Reli- gious and Theological Abstracts. The journal is archived by Library and Archives Canada and is accessible for consultation and research at the Electronic Collection site maintained by Library and Archives Canada (for a direct link, click here). Volume 10, Article 17 DAVID P. MELVIN, DIVINE MEDIATION AND THE RISE OF CIVILIZATION IN MESOPOTAMIAN LITERATURE AND IN GENESIS 1–11 1 2 JOURNAL OF HEBREW SCRIPTURES DIVINE MEDIATION AND THE RISE OF CIVILIZATION IN MESOPOTAMIAN LITERATURE AND IN GENESIS 1–11 DAVID P. MELVIN BAYLOR UNIVERSITY INTRODUCTION In the study of Genesis 1–11, it is common for scholars to make comparisons between the biblical material and ancient Near East- ern myths. The discovery of large numbers of texts from Mesopo- tamia and Ugarit during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries created a veritable deluge of comparative studies of the primeval history. While the observation of the many continuities between Genesis 1–11 and Mesopotamian myths has contributed greatly to our understanding of this portion of the biblical text, it is also im- portant to note the discontinuities between the biblical and extra- biblical material. One such discontinuity relates to the origin of human civilization. In Mesopotamian myths, civilization arises via the intervention of gods or other divine beings. It is portrayed variously as a gift bestowed directly upon humanity, an institution preceding the creation of humanity (via the creation of patron dei- ties of various technologies), or the bestowal of knowledge upon humans by gods, sometimes through intermediary beings. -

The Animated Temple and Its Agency in the Urban Life of the City in Ancient Mesopotamia Beate Pongratz-Leisten, NYU, ISAW

religions Article The Animated Temple and Its Agency in the Urban Life of the City in Ancient Mesopotamia Beate Pongratz-Leisten, NYU, ISAW Beate Pongratz-Leisten Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (ISAW), New York University, New York, NY 10028, USA; [email protected] Abstract: In ancient Mesopotamia, the functions of the temple were manifold. It could operate as an administrative center, as a center of learning, as a place of jurisdiction, as a center for healing, and as an economic institution, as indicated in both textual and archaeological sources. All these functions involved numerous and diverse personnel and generated interaction with the surrounding world, thereby turning the temple into the center of urban life. Because the temple fulfilled all these functions in addition to housing the divinity, it acquired agency in its own right. Thus, temple, city, and divinity could merge into concerted action. It is this aspect of the temple that lies at the center of the following considerations. Keywords: temple; divinity; community; agency “Arbela, O Arbela, heaven without equal, Arbela! ... Arbela, temple of reason and Citation: Pongratz-Leisten, Beate. 1 2021. The Animated Temple and Its counsel!” (Livingstone 1989, no. 8). This Neo-Assyrian salute to the city of Arbela stands Agency in the Urban Life of the City at the end of a long history of texts that ponder the origin of temples and cities and their in Ancient Mesopotamia Beate role in the cosmic plan. Glorifying the city, it conflates it with both the divine realm and Pongratz-Leisten, NYU, ISAW. the temple in terms of agency in a manner that is typical of the ancient world view and Religions 12: 638. -

Part One by Peter Goodgame

The Giza Discovery Part One By Peter Goodgame The Giza Discovery Volume 1 By Peter Goodgame Index 1. The Search for the Hidden Tomb The Hallway of Osiris The French Initiative The Hawass Initiative The Giza Wall 2. The Myth and Religion of Osiris the God Egyptian Religion The Myth of Osiris The Symbols of Osiris The Pyramid Texts Giza and the Cult of Osiris The Mysteries of Osiris 3. The Saviors of the Ancient World The Real Debate Ugaritic Baal Melqart of Tyre Adonis of Byblos Eshmun of Sidon Dumuzi of Sumeria Osiris of Egypt The Osiris Agenda 4. Egypt's Forgotten Origins Flinders Petrie The Dynastic Race The Rise, Fall and Resurrection of a Theory Data: The Nakada Artifacts Data: Writing Data: Architecture The Square Boat Invasion The Great Migration 5. The Spirit World and Civilization The Sumerian Perspective The Creation of Man The Great Flood The Transfer of Divine Authority The Hebrew Perspective The Creation of Man The Crime and Banishment of Cain Eridu: the Place of Descent The Great Flood The Tower of Babel Enmerkar and the Shrine of the Abzu Evidence for Eridu's Tower The Egyptian Connection The Historical Osiris 6. Domination by Deception Israel's God and the Gods of Sumer Enki Unmasked History is Written by the Victor The Biblical Response God Against the Gods God's Nation The Kosmokrators and the Occult Hermeticism Gnosticism The Kabbalah The Kosmokrators, Egypt and Freemasonry The End of the "World Powers" 7. The Second Coming of ... Introduction The Beast The Seven Kings of Satan The First Seal of the Apocalypse Seven Kings -

Abhiyoga Jain Gods

A babylonian goddess of the moon A-a mesopotamian sun goddess A’as hittite god of wisdom Aabit egyptian goddess of song Aakuluujjusi inuit creator goddess Aasith egyptian goddess of the hunt Aataentsic iriquois goddess Aatxe basque bull god Ab Kin Xoc mayan god of war Aba Khatun Baikal siberian goddess of the sea Abaangui guarani god Abaasy yakut underworld gods Abandinus romano-celtic god Abarta irish god Abeguwo melansian rain goddess Abellio gallic tree god Abeona roman goddess of passage Abere melanisian goddess of evil Abgal arabian god Abhijit hindu goddess of fortune Abhijnaraja tibetan physician god Abhimukhi buddhist goddess Abhiyoga jain gods Abonba romano-celtic forest goddess Abonsam west african malicious god Abora polynesian supreme god Abowie west african god Abu sumerian vegetation god Abuk dinkan goddess of women and gardens Abundantia roman fertility goddess Anzu mesopotamian god of deep water Ac Yanto mayan god of white men Acacila peruvian weather god Acala buddhist goddess Acan mayan god of wine Acat mayan god of tattoo artists Acaviser etruscan goddess Acca Larentia roman mother goddess Acchupta jain goddess of learning Accasbel irish god of wine Acco greek goddess of evil Achiyalatopa zuni monster god Acolmitztli aztec god of the underworld Acolnahuacatl aztec god of the underworld Adad mesopotamian weather god Adamas gnostic christian creator god Adekagagwaa iroquois god Adeona roman goddess of passage Adhimukticarya buddhist goddess Adhimuktivasita buddhist goddess Adibuddha buddhist god Adidharma buddhist goddess