Burn Your Way to Success Studies in the Mesopotamian Ritual And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hologram Curaçao, 2018 First Edition

Hologram Curaçao, 2018 First edition This book is written by; John H Baselmans-Oracle Cover design are from the hand of; John H Baselmans-Oracle Illustrations Different artists With thanks to all those people who are supporting me. Copyrights All rights on text and drawings reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from LoBa productions, except for brief quotes with an acknowledgement. Bulk copies of this book can be obtained by contacting LoBa Productions at http://www.world-of-positive-energy.com. No part of this work is intended to be a substitute for professional medical, pastoral or psychological guidance or treatment. Production/Design: LoBa Productions ISBN 978-1-387-72155-9 Hologram Is de wereld een hologram? John H Baselmans - Oracle 4 HOLOGRAM Is de wereld een hologram? 5 Inhoud Voorwoord 8 Hoofdstuk 1 1-1 In den beginnen 11 1-2 Om gewoon eens over na te denken 14 1-3 Wat is het geheim rond en om de Anunnaki? 16 1-4 De tabletten 26 1-5 Tablet van Lord Enki 31 1-6 Even nog wat verder denken 53 1-7 Parallel Universum / Parallel Wereld 55 1-8 Even het woordje “onderwereld” 57 1-9 Wat de geleerden zeggen over Goden 59 1-10 Enkele goden vernoemd 76 1-11 Het Heelal / Universum en haar goden 87 1-12 Licht 108 Hoofdstuk 2 2-1 Inleiding 117 2-2 De onder- en de bovenwereld, bestaan deze? 117 2-3 Waarom zijn het vaticaan en de joodse gemeenschap zo bang? 124 -

1 Inanna Research Script

INANNA RESEARCH SCRIPT (to be cut and shaped for performance) By Peggy Firestone Based on Translations of Clay Tablets from Sumer By Samuel Noah Kramer 1 [email protected] (773) 384-5802 © 2008 CAST OF CHARACTERS In order of appearance Narrators ………………………………… Storytellers & Timekeepers Inanna …………………………………… Queen of Heaven and Earth, Goddess, Immortal Enki ……………………………………… Creator & Organizer of Earth’s Living Things, Manager of the Gods & Goddesses, Trickster God, Inanna’s Grandfather An ………………………………………. The Sky God Ki ………………………………………. The Earth Goddess (also known as Ninhursag) Enlil …………………………………….. The Air God, inventor of all things useful in the Universe Nanna-Sin ………………………………. The Moon God, Immortal, Father of Inanna Ningal …………………………………... The Moon Goddess, Immortal, Mother of Inanna Lilith ……………………………………. Demon of Desolation, Protector of Freedom Anzu Bird ………………………………. An Unholy (Holy) Trinity … Demon bird, Protector of Cattle Snake that has no Grace ………………. Tyrant Protector Snake Gilgamesh ……………………………….. Hero, Mortal, Inanna’s first cousin, Demi-God of Uruk Isimud ………………………………….. Enki’s Janus-faced messenger Ninshubur ……………………………… Inanna’s lieutenant, Goddess of the Rising Sun, Queen of the East Lahamma Enkums ………………………………… Monster Guardians of Enki’s Shrine House Giants of Eridu Utu ……………………………………… Sun God, Inanna’s Brother Dumuzi …………………………………. Shepherd King of Uruk, Inanna’s husband, Enki’s son by Situr, the Sheep Goddess Neti ……………………………………… Gatekeeper to the Nether World Ereshkigal ……………………………. Queen of the -

Cuneiform Monographs

VANSTIPHOUT/F1_i-vi 4/26/06 8:08 PM Page ii Cuneiform Monographs Editors t. abusch ‒ m.j. geller s.m. maul ‒ f.a.m. wiggerman VOLUME 35 frontispiece 4/26/06 8:09 PM Page ii Stip (Dr. H. L. J. Vanstiphout) VANSTIPHOUT/F1_i-vi 4/26/06 8:08 PM Page iii Approaches to Sumerian Literature Studies in Honour of Stip (H. L. J. Vanstiphout) Edited by Piotr Michalowski and Niek Veldhuis BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2006 VANSTIPHOUT/F1_i-vi 4/26/06 8:08 PM Page iv This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on http: // catalog.loc.gov ISSN 0929-0052 ISBN-10 90 04 15325 X ISBN-13 978 90 04 15325 7 © Copyright 2006 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Academic Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. printed in the netherlands VANSTIPHOUT/F1_i-vi 4/26/06 8:08 PM Page v CONTENTS Piotr Michalowski and Niek Veldhuis H. L. J. Vanstiphout: An Appreciation .............................. 1 Publications of H. -

In the Wake of the Compendia Science, Technology, and Medicine in Ancient Cultures

In the Wake of the Compendia Science, Technology, and Medicine in Ancient Cultures Edited by Markus Asper Philip van der Eijk Markham J. Geller Heinrich von Staden Liba Taub Volume 3 In the Wake of the Compendia Infrastructural Contexts and the Licensing of Empiricism in Ancient and Medieval Mesopotamia Edited by J. Cale Johnson DE GRUYTER ISBN 978-1-5015-1076-2 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-1-5015-0250-7 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-1-5015-0252-1 ISSN 2194-976X Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2015 Walter de Gruyter Inc., Boston/Berlin Typesetting: Meta Systems Publishing & Printservices GmbH, Wustermark Printing and binding: Hubert & Co. GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Notes on Contributors Florentina Badalanova Geller is Professor at the Topoi Excellence Cluster at the Freie Universität Berlin. She previously taught at the University of Sofia and University College London, and is currently on secondment from the Royal Anthropological Institute (London). She has published numerous papers and is also the author of ‘The Bible in the Making’ in Imagining Creation (2008), Qurʾān in Vernacular: Folk Islam in the Balkans (2008), and 2 (Slavonic Apocalypse of) Enoch: Text and Context (2010). Siam Bhayro was appointed Senior Lecturer in Early Jewish Studies in the Department of Theology and Religion, University of Exeter, in 2012, having previously been Lecturer in Early Jewish Studies since 2007. -

ANIMAL SACRIFICE in ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN RELIGION The

CHAPTER FOURTEEN ANIMAL SACRIFICE IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN RELIGION JOANN SCURLOCK The relationship between men and gods in ancient Mesopotamia was cemented by regular offerings and occasional sacrifices of ani mals. In addition, there were divinatory sacrifices, treaty sacrifices, and even "covenant" sacrifices. The dead, too, were entitled to a form of sacrifice. What follows is intended as a broad survey of ancient Mesopotamian practices across the spectrum, not as an essay on the developments that must have occurred over the course of several millennia of history, nor as a comparative study of regional differences. REGULAR OFFERINGS I Ancient Mesopotamian deities expected to be fed twice a day with out fail by their human worshipers.2 As befitted divine rulers, they also expected a steady diet of meat. Nebuchadnezzar II boasts that he increased the offerings for his gods to new levels of conspicuous consumption. Under his new scheme, Marduk and $arpanitum were to receive on their table "every day" one fattened ungelded bull, fine long fleeced sheep (which they shared with the other gods of Baby1on),3 fish, birds,4 bandicoot rats (Englund 1995: 37-55; cf. I On sacrifices in general, see especially Dhorme (1910: 264-77) and Saggs (1962: 335-38). 2 So too the god of the Israelites (Anderson 1992: 878). For specific biblical refer ences to offerings as "food" for God, see Blome (1934: 13). To the term tamid, used of this daily offering in Rabbinic sources, compare the ancient Mesopotamian offering term gimi "continual." 3 Note that, in the case of gods living in the same temple, this sharing could be literal. -

Judeans in Babylonia a Study of Deportees in the Sixth and Fifth Centuries BCE

Tero Alstola Judeans in Babylonia A Study of Deportees in the Sixth and Fifth Centuries BCE ACADEMIC DISSERTATION TO BE PUBLICLY DISCUSSED, BY DUE PERMISSION OF THE FACULTY OF THEOLOGY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI IN AUDITORIUM XII OF THE UNIVERSITY MAIN BUILDING, ON THE 17TH OF JANUARY, 2018 AT 12 O’CLOCK. This dissertation project has been financially supported by the ERC Starting Grant project ‘By the Rivers of Babylon: New Perspectives on Second Temple Judaism from Cuneiform Texts’ and by the Centre of Excellence in Changes in Sacred Texts and Traditions, funded by the Academy of Finland. Cover illustration by Suvi Tuominen ISBN 978-951-51-3831-6 (paperback) ISBN 978-951-51-3832-3 (PDF) Unigrafia Oy Helsinki 2017 SUMMARY Judeans in Babylonia: A Study of Deportees in the Sixth and Fifth Centuries BCE The dissertation investigates Judean deportees in Babylonia in the sixth and fifth centuries BCE. These people arrived in Babylonia from Judah in the early sixth century BCE, being but one of numerous ethnic groups deported and resettled by King Nebuchadnezzar II. Naming practices among many deportee groups have been thoroughly analysed, but there has been little interest in writing a socio-historical study of Judeans or other immigrants in Babylonia on the basis of cuneiform sources. The present dissertation fills this gap by conducting a case study of Judean deportees and placing its results in the wider context of Babylonian society. The results from the study of Judeans are evaluated by using a group of Neirabian deportees as a point of comparison. The sources of this study consist of 289 clay tablets written in Akkadian cuneiform. -

The Lost Book of Enki.Pdf

L0ST BOOK °f6NK1 ZECHARIA SITCHIN author of The 12th Planet • . FICTION/MYTHOLOGY $24.00 TH6 LOST BOOK OF 6NK! Will the past become our future? Is humankind destined to repeat the events that occurred on another planet, far away from Earth? Zecharia Sitchin’s bestselling series, The Earth Chronicles, provided humanity’s side of the story—as recorded on ancient clay tablets and other Sumerian artifacts—concerning our origins at the hands of the Anunnaki, “those who from heaven to earth came.” In The Lost Book of Enki, we can view this saga from a dif- ferent perspective through this richly con- ceived autobiographical account of Lord Enki, an Anunnaki god, who tells the story of these extraterrestrials’ arrival on Earth from the 12th planet, Nibiru. The object of their colonization: gold to replenish the dying atmosphere of their home planet. Finding this precious metal results in the Anunnaki creation of homo sapiens—the human race—to mine this important resource. In his previous works, Sitchin com- piled the complete story of the Anunnaki ’s impact on human civilization in peacetime and in war from the frag- ments scattered throughout Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian, Assyrian, Hittite, Egyptian, Canaanite, and Hebrew sources- —the “myths” of all ancient peoples in the old world as well as the new. Missing from these accounts, however, was the perspective of the Anunnaki themselves What was life like on their own planet? What motives propelled them to settle on Earth—and what drove them from their new home? Convinced of the existence of a now lost book that formed the basis of THE lost book of ENKI MFMOHCS XND PKjOPHeCieS OF XN eXTfCXUfCWJTWXL COD 2.6CHXPJA SITCHIN Bear & Company Rochester, Vermont — Bear & Company One Park Street Rochester, Vermont 05767 www.InnerTraditions.com Copyright © 2002 by Zecharia Sitchin All rights reserved. -

Thy Name Is Slave?

Verhandeling voorgelegd aan de Faculteit Letteren en Wijsbegeerte Voor het behalen van de graad van: Master in de Oosterse Talen en Culturen door: LIESELOT VANDORPE Academiejaar 2009-2010 Universiteit Gent Thy name is slave? The slave onomasticon of Old Babylonian Sippar. Promotor: Dr. K. De Graef 2 TABLE OF CONTENT List of Abbreviations 5 I. Introduction 6 A. Purpose 12 B. Status Quaestionis 13 C. Cultural Historical perspective 14 II. Slave documents 16 A. Inheritance and will documents 18 B. Purchase papers and silver loans 18 C. Donation 20 D. Litigation 20 E. Hire 20 F. Adoption/manumission 21 G. Dowry and wedding certificates 21 H. Others 22 III. Slave names unraveled 23 A. Slaves and their personal names 23 a. Male slave names 24 b. Female slave names 35 B. Ethnography and uniqueness of the slave name 50 C. Thy name is slave? 51 IV. Construction of slave names 53 A. Slave names according to Stamm 53 B. Sub-categories among Sipparian slaves 54 a. Wishes and prayers towards the master 54 b. Questions formulated to the master 55 c. Statements of trust towards the master 56 d. Praise for the master 56 e. Small categories of slave PN’s 57 1. Expression of Tenderness 57 2. Praise for physical defaults 57 3. Reference to the character and intellect of slaves 58 4. References to animals and plants 58 5. Names with geographical elements 58 6. Signs of imprisonment 58 C. Male names for female slaves 58 D. Theophoric elements in slave PN’s 59 E. Slaves and nadītu priestesses 61 F. -

Lambert Walcot Kadmos 4 Dunnu

WARNING OF COPYRIGHT RESTRICTIONS1 The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, U.S. Code) governs the maKing of photocopies or other reproductions of the copyright materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, library and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than in private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user maKes a reQuest for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. The Yale University Library reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order, if, in its judgement fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. 137 C.F.R. §201.14 2018 KADMOS ZEITSCHRIFT FOR VOR- UND FRÜHGRIECHISCIIE EPIGRAPHIK IN VERBINDUNG MIT: EMMETT L. BENNETT-MADISON • WILLIAM C. BRICE-MANCHESTER PORPHYRIOS DIKAIOS-WALTHAM • KONSTANTINOS D. KTISTOPOULOS ATHENN. OLIVIER MASSON-PARIS • PIERO MERIGGI-PAVIA • FRITZ SCHACHE RMEYR-WIEN - JOHANNES SUNDWALL-HELSINGFORS HERAUSGEGEBEN VON ERNST GRUMACH BAND IV / HEFT 1 WA LTER DE G R U Y T E R & CO. / BERLIN LUNG - J. G. VERLAG 1TAhCOMP. ~ U CHHANDLUUNG -EORGG REIMER SK IKARL J.TRUBNER TTVE 1965 WILFRED G. LAMBERT and PETER WALCOT1 A NEW BABYLONIAN THEOGONY AND HESIOD A volume of cuneiform texts just published by the British Museum2 contains a short theogony, which is of interest to Classical scholars since it is closer to Hesiod's opening list of gods than any other cuneiform material of this category. -

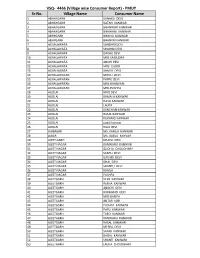

Sr No. Village Name Consumer Name VSQ- 4466 (Village Wise Consumer Report)

VSQ- 4466 (Village wise Consumer Report) - PMUY Sr No. Village Name Consumer Name 1 ABHAYGARH KANAKU DEVI 2 ABHAYGARH RATAN KANWAR 3 ABHAYGARH BHANWAR KANWAR 4 ABHAYGARH BHAWANI KANWAR 5 ABHYGARH BHIKHU KANWAR 6 ABHYGARH BHANVRI KANWAR 7 ACHALAWATA SUNDARI DEVI 8 ACHALAWATA SHOBHA DEVI 9 ACHALAWATA DAKHU DEVI 10 ACHALAWATA MRS SAMUDRA 11 ACHALAWATA ANOPI DEVI 12 ACHALAWATA MRS GUDDI 13 ACHALAWATA KAMLA DEVI 14 ACHALAWATAN MOOLI DEVI 15 ACHALAWATAN PAPPU DEVI 16 ACHALAWATAN MRS BHANVARI 17 ACHALAWATAN MRS PUSHPA 18 AGOLAI HIRO DEVI 19 AGOLAI KAMALA KANWAR 20 AGOLAI HAVA KANWAR 21 AGOLAI LALITA 22 AGOLAI KANCHAN KANWAR 23 AGOLAI RASAL KANWAR 24 AGOLAI RUKAMO KANWAR 25 AGOLAI guddi kanwar 26 AGOLAI RAJO DEVI 27 AJABASAR MS. KAMLA KANWAR 28 AJBAR MS. BABLU KANVAR 29 AJEET GARH DHAPU DEVI 30 AJEET NAGAR KANWARU KANWAR 31 AJEET NAGAR GUDIYA CHOUDHARY 32 AJEET NAGAR SANTU DEVI 33 AJEET NAGAR GAVARI DEVI 34 AJEET NAGAR DHAI DEVI 35 AJEET NAGAR SHANTU DEVI 36 AJEET NAGAR KAMLA . 37 AJEET NAGAR PUSHPA . 38 AJEETGARH VEER KANWAR 39 AJEETGARH REKHA KANWAR 40 AJEETGARH ANACHI DEVI 41 AJEETGARH RUKHAMO DEVI 42 AJEETGARH MRS BABITA 43 AJEETGARH ANTAR KOR 44 AJEETGARH PUSHPA KANWAR 45 AJEETGARH PAPU KANWAR 46 AJEETGARH TARO KANWAR 47 AJEETGARH KANWARU KANWAR 48 AJEETGARH RASAL KANWAR 49 AJEETGARH MEERA DEVI 50 AJEETGARH SAYAR KANWAR 51 AJEETGARH BADAL KANWAR 52 AJEETGARH SHANTI KANWAR 53 AJEETGARH LALITA CHOUDHARY Sr No. Village Name Consumer Name 54 AJEETGARH PEP KANWAR 55 AJEETGARH RASAL KANWAR 56 AJEETGARH JASU KANWAR 57 AJEETGARH LILA KANWAR 58 AJEETGARH KHAMMA DEVI 59 AJIT GADH SUGAN KANWAR 60 AJITGARH CHIMU DEVI 61 AJITGARH KANWARU KANWAR 62 AJJETGADH SOHNI DEVI 63 AKADEEYAWALA MAGEJ KANWAR 64 ALIDAS NAGAR PAPPU KANWAR 65 ALIDAS NAGAR PARVATI DEVI 66 ALIDAS NAGAR NAINU KANWAR 67 ALIDAS NAGAR MOHANI DEVI 68 ALIDAS NAGAR PISTA DEVI 69 ALIDAS NAGAR PRAKASH KANWAR 70 ALIDAS NAGAR NAKHTU DEVI 71 ALIDAS NAGAR DHAPU . -

Assyrian Dictionary

oi.uchicago.edu THE ASSYRIAN DICTIONARY OF THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO EDITORIAL BOARD IGNACE J. GELB, THORKILD JACOBSEN, BENNO LANDSBERGER, A. LEO OPPENHEIM 1956 PUBLISHED BY THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE, CHICAGO 37, ILLINOIS, U.S.A. AND J. J. AUGUSTIN VERLAGSBUCHHANDLUNG, GLOCKSTADT, GERMANY oi.uchicago.edu INTERNATIONAL STANDARD BOOK NUMBER: 0-918986-11-7 (SET: 0-918986-05-2) LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG CARD NUMBER: 56-58292 ©1956 by THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS Fifth Printing 1995 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA COMPOSITION BY J. J. AUGUSTIN, GLUCKSTADT oi.uchicago.edu THE ASSYRIAN DICTIONARY VOLUME 5 G A. LEO OPPENHEIM, EDITOR-IN-CHARGE WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF ERICA REINER AND MICHAEL B. ROWTON RICHARD T. HALLOCK, EDITORIAL SECRETARY oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu Foreword The present volume of the CAD follows in general the pattern established in Vol. 6 (H). Only in minor points such as the organization of the semantic section, and especially in the lay-out of the printed text, have certain simplifications and improvements been introduced which are meant to facilitate the use of the book. On p. 149ff. additions and corrections to Vol. 6 are listed and it is planned to continue this practice in the subsequent volumes of the CAD in order to list new words and important new references, as well as to correct mistakes made in previous volumes. The Supplement Volume will collect and republish alphabetically all that material. The Provisional List of Bibliographical Abbreviations has likewise been brought a jour. -

Asher-Greve / Westenholz Goddesses in Context ORBIS BIBLICUS ET ORIENTALIS

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2013 Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources Asher-Greve, Julia M ; Westenholz, Joan Goodnick Abstract: Goddesses in Context examines from different perspectives some of the most challenging themes in Mesopotamian religion such as gender switch of deities and changes of the status, roles and functions of goddesses. The authors incorporate recent scholarship from various disciplines into their analysis of textual and visual sources, representations in diverse media, theological strategies, typologies, and the place of image in religion and cult over a span of three millennia. Different types of syncretism (fusion, fission, mutation) resulted in transformation and homogenization of goddesses’ roles and functions. The processes of syncretism (a useful heuristic tool for studying the evolution of religions and the attendant political and social changes) and gender switch were facilitated by the fluidity of personality due to multiple or similar divine roles and functions. Few goddesses kept their identity throughout the millennia. Individuality is rare in the iconography of goddesses while visual emphasis is on repetition of generic divine figures (hieros typos) in order to retain recognizability of divinity, where femininity is of secondary significance. The book demonstrates that goddesses were never marginalized or extrinsic and thattheir continuous presence in texts, cult images, rituals, and worship throughout Mesopotamian history is testimony to their powerful numinous impact. This richly illustrated book is the first in-depth analysis of goddesses and the changes they underwent from the earliest visual and textual evidence around 3000 BCE to the end of ancient Mesopotamian civilization in the Seleucid period.