Newly Recovered Content from the Ur Version of the Sumerian Flood Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cuneiform Monographs

VANSTIPHOUT/F1_i-vi 4/26/06 8:08 PM Page ii Cuneiform Monographs Editors t. abusch ‒ m.j. geller s.m. maul ‒ f.a.m. wiggerman VOLUME 35 frontispiece 4/26/06 8:09 PM Page ii Stip (Dr. H. L. J. Vanstiphout) VANSTIPHOUT/F1_i-vi 4/26/06 8:08 PM Page iii Approaches to Sumerian Literature Studies in Honour of Stip (H. L. J. Vanstiphout) Edited by Piotr Michalowski and Niek Veldhuis BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2006 VANSTIPHOUT/F1_i-vi 4/26/06 8:08 PM Page iv This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on http: // catalog.loc.gov ISSN 0929-0052 ISBN-10 90 04 15325 X ISBN-13 978 90 04 15325 7 © Copyright 2006 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Academic Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. printed in the netherlands VANSTIPHOUT/F1_i-vi 4/26/06 8:08 PM Page v CONTENTS Piotr Michalowski and Niek Veldhuis H. L. J. Vanstiphout: An Appreciation .............................. 1 Publications of H. -

Burn Your Way to Success Studies in the Mesopotamian Ritual And

Burn your way to success Studies in the Mesopotamian Ritual and Incantation Series Šurpu by Francis James Michael Simons A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics, Ancient History and Archaeology School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham March 2017 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The ritual and incantation series Šurpu ‘Burning’ is one of the most important sources for understanding religious and magical practice in the ancient Near East. The purpose of the ritual was to rid a sufferer of a divine curse which had been inflicted due to personal misconduct. The series is composed chiefly of the text of the incantations recited during the ceremony. These are supplemented by brief ritual instructions as well as a ritual tablet which details the ceremony in full. This thesis offers a comprehensive and radical reconstruction of the entire text, demonstrating the existence of a large, and previously unsuspected, lacuna in the published version. In addition, a single tablet, tablet IX, from the ten which comprise the series is fully edited, with partitur transliteration, eclectic and normalised text, translation, and a detailed line by line commentary. -

The Sumerian King List the Sumerian King List (SKL) Dates from Around 2100 BCE—Near the Time When Abram Was in Ur

BcResources Genesis The Sumerian King List The Sumerian King List (SKL) dates from around 2100 BCE—near the time when Abram was in Ur. Most ANE scholars (following Jacobsen) attribute the original form of the SKL to Utu-hejel, king of Uruk, and his desire to legiti- mize his reign after his defeat of the Gutians. Later versions included a reference or Long Chronology), 1646 (Middle to the Great Flood and prefaced the Chronology), or 1582 (Low or Short list of postdiluvian kings with a rela- Chronology). The following chart uses tively short list of what appear to be the Middle Chronology. extremely long-reigning antediluvian Text. The SKL text for the following kings. One explanation: transcription chart was originally in a narrative form or translation errors resulting from and consisted of a composite of several confusion of the Sumerian base-60 versions (see Black, J.A., Cunningham, and the Akkadian base-10 systems G., Fluckiger-Hawker, E, Robson, E., of numbering. Dividing each ante- and Zólyomi, G., The Electronic Text diluvian figure by 60 returns reigns Corpus of Sumerian Literature (http:// in harmony with Biblical norms (the www-etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk/), Oxford bracketed figures in the antediluvian 1998-). The text was modified by the portion of the chart). elimination of manuscript references Final versions of the SKL extended and by the addition of alternative the list to include kings up to the reign name spellings, clarifying notes, and of Damiq-ilicu, king of Isin (c. 1816- historical dates (typically in paren- 1794 BCE). thesis or brackets). The narrative was Dates. -

Lambert Walcot Kadmos 4 Dunnu

WARNING OF COPYRIGHT RESTRICTIONS1 The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, U.S. Code) governs the maKing of photocopies or other reproductions of the copyright materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, library and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than in private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user maKes a reQuest for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. The Yale University Library reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order, if, in its judgement fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. 137 C.F.R. §201.14 2018 KADMOS ZEITSCHRIFT FOR VOR- UND FRÜHGRIECHISCIIE EPIGRAPHIK IN VERBINDUNG MIT: EMMETT L. BENNETT-MADISON • WILLIAM C. BRICE-MANCHESTER PORPHYRIOS DIKAIOS-WALTHAM • KONSTANTINOS D. KTISTOPOULOS ATHENN. OLIVIER MASSON-PARIS • PIERO MERIGGI-PAVIA • FRITZ SCHACHE RMEYR-WIEN - JOHANNES SUNDWALL-HELSINGFORS HERAUSGEGEBEN VON ERNST GRUMACH BAND IV / HEFT 1 WA LTER DE G R U Y T E R & CO. / BERLIN LUNG - J. G. VERLAG 1TAhCOMP. ~ U CHHANDLUUNG -EORGG REIMER SK IKARL J.TRUBNER TTVE 1965 WILFRED G. LAMBERT and PETER WALCOT1 A NEW BABYLONIAN THEOGONY AND HESIOD A volume of cuneiform texts just published by the British Museum2 contains a short theogony, which is of interest to Classical scholars since it is closer to Hesiod's opening list of gods than any other cuneiform material of this category. -

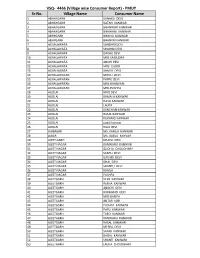

Sr No. Village Name Consumer Name VSQ- 4466 (Village Wise Consumer Report)

VSQ- 4466 (Village wise Consumer Report) - PMUY Sr No. Village Name Consumer Name 1 ABHAYGARH KANAKU DEVI 2 ABHAYGARH RATAN KANWAR 3 ABHAYGARH BHANWAR KANWAR 4 ABHAYGARH BHAWANI KANWAR 5 ABHYGARH BHIKHU KANWAR 6 ABHYGARH BHANVRI KANWAR 7 ACHALAWATA SUNDARI DEVI 8 ACHALAWATA SHOBHA DEVI 9 ACHALAWATA DAKHU DEVI 10 ACHALAWATA MRS SAMUDRA 11 ACHALAWATA ANOPI DEVI 12 ACHALAWATA MRS GUDDI 13 ACHALAWATA KAMLA DEVI 14 ACHALAWATAN MOOLI DEVI 15 ACHALAWATAN PAPPU DEVI 16 ACHALAWATAN MRS BHANVARI 17 ACHALAWATAN MRS PUSHPA 18 AGOLAI HIRO DEVI 19 AGOLAI KAMALA KANWAR 20 AGOLAI HAVA KANWAR 21 AGOLAI LALITA 22 AGOLAI KANCHAN KANWAR 23 AGOLAI RASAL KANWAR 24 AGOLAI RUKAMO KANWAR 25 AGOLAI guddi kanwar 26 AGOLAI RAJO DEVI 27 AJABASAR MS. KAMLA KANWAR 28 AJBAR MS. BABLU KANVAR 29 AJEET GARH DHAPU DEVI 30 AJEET NAGAR KANWARU KANWAR 31 AJEET NAGAR GUDIYA CHOUDHARY 32 AJEET NAGAR SANTU DEVI 33 AJEET NAGAR GAVARI DEVI 34 AJEET NAGAR DHAI DEVI 35 AJEET NAGAR SHANTU DEVI 36 AJEET NAGAR KAMLA . 37 AJEET NAGAR PUSHPA . 38 AJEETGARH VEER KANWAR 39 AJEETGARH REKHA KANWAR 40 AJEETGARH ANACHI DEVI 41 AJEETGARH RUKHAMO DEVI 42 AJEETGARH MRS BABITA 43 AJEETGARH ANTAR KOR 44 AJEETGARH PUSHPA KANWAR 45 AJEETGARH PAPU KANWAR 46 AJEETGARH TARO KANWAR 47 AJEETGARH KANWARU KANWAR 48 AJEETGARH RASAL KANWAR 49 AJEETGARH MEERA DEVI 50 AJEETGARH SAYAR KANWAR 51 AJEETGARH BADAL KANWAR 52 AJEETGARH SHANTI KANWAR 53 AJEETGARH LALITA CHOUDHARY Sr No. Village Name Consumer Name 54 AJEETGARH PEP KANWAR 55 AJEETGARH RASAL KANWAR 56 AJEETGARH JASU KANWAR 57 AJEETGARH LILA KANWAR 58 AJEETGARH KHAMMA DEVI 59 AJIT GADH SUGAN KANWAR 60 AJITGARH CHIMU DEVI 61 AJITGARH KANWARU KANWAR 62 AJJETGADH SOHNI DEVI 63 AKADEEYAWALA MAGEJ KANWAR 64 ALIDAS NAGAR PAPPU KANWAR 65 ALIDAS NAGAR PARVATI DEVI 66 ALIDAS NAGAR NAINU KANWAR 67 ALIDAS NAGAR MOHANI DEVI 68 ALIDAS NAGAR PISTA DEVI 69 ALIDAS NAGAR PRAKASH KANWAR 70 ALIDAS NAGAR NAKHTU DEVI 71 ALIDAS NAGAR DHAPU . -

Mesopotamian Culture

MESOPOTAMIAN CULTURE WORK DONE BY MANUEL D. N. 1ºA MESOPOTAMIAN GODS The Sumerians practiced a polytheistic religion , with anthropomorphic monotheistic and some gods representing forces or presences in the world , as he would later Greek civilization. In their beliefs state that the gods originally created humans so that they serve them servants , but when they were released too , because they thought they could become dominated by their large number . Many stories in Sumerian religion appear homologous to stories in other religions of the Middle East. For example , the biblical account of the creation of man , the culture of The Elamites , and the narrative of the flood and Noah's ark closely resembles the Assyrian stories. The Sumerian gods have distinctly similar representations in Akkadian , Canaanite religions and other cultures . Some of the stories and deities have their Greek parallels , such as the descent of Inanna to the underworld ( Irkalla ) resembles the story of Persephone. COSMOGONY Cosmogony Cosmology sumeria. The universe first appeared when Nammu , formless abyss was opened itself and in an act of self- procreation gave birth to An ( Anu ) ( sky god ) and Ki ( goddess of the Earth ), commonly referred to as Ninhursag . Binding of Anu (An) and Ki produced Enlil , Mr. Wind , who eventually became the leader of the gods. Then Enlil was banished from Dilmun (the home of the gods) because of the violation of Ninlil , of which he had a son , Sin ( moon god ) , also known as Nanna . No Ningal and gave birth to Inanna ( goddess of love and war ) and Utu or Shamash ( the sun god ) . -

Sibel Özbudun

Sibel Özbudun SİYASAL İKTİDARIN KURULMA VE KURUMSALLAŞMA SURECİNDE TÖRENLERİN İŞLEVLERİ 7H17IRC7IR K O P L 7 IR ARAŞTIRMA - İNCELEME DİZİSİ ANAHTAR KİTAPLAR YAYINEVİ Kloüfarer Cad. İletişim Han No:7 Kat:2 34400 Cağaloğlu-İstanbul Tel.: (0.212) 518 54 42 Fax: (0.212)638 11 12 SİBEL ÖZBUDUN AYİNDEN TÖRENE SİYASAL İKTİDARIN KURULMA VE KURUMSALLAŞMA SÜRECİNDE TÖRENLERİN İŞLEVLERİ AYİNDEN TÖRENE SİBEL ÖZBUDUN Kitabın Özgün Adı: Ayinden Törene Yayın Hakları: © Sibel Özbudun / Anahtar Kitaplar - 1997 Kapak Grafik: İrfan Ertel Kapak Resmi Tasarımlı Mustafa Deniz Arun Kapak Filmi: Ebru Grafik Baskı: Ceylan Matbaacılık Birinci Basım: Mart 1997 ISBN 975-7787-52-3 SİBEL ÖZBUDUN AYİNDEN • • TÖRENE SİYASAL İKTİDARIN KURULMA VE KURUMSALLAŞMA SÜRECİNDE TÖRENLERİN İŞLEVLERİ Geleceğin ‘töremiz’ toplumu için... S.Ö. İÇİNDEKİLER Önsöz........................................... .............................. 9 1. Bölüm: Kuramsal Çerçeve, Yöntem, Tanımlar, Yaklaşımlar........................................................ 11 1.1. Kuramsal Çerçeve.............................................................. 11 1.2. Yöntem................................................ *........ .................. 13 1.3. Tanımlar........................................................................... 16 1.4. Yaklaşımlar....................................................................... 21 1.4.1. Antropolojide Başlıca Yaklaşımlar............................. 21 1.4.2. Mitos ve Ayin Hareketi............................................. 24 1.4.3. Son Dönem Yaklaşımları......................................... -

The Mesopotamians Hungered for What? Literature, Material Culture, and Other Histories

Recebido: December 28, 2017│ Accepted: January 12, 2018 THE MESOPOTAMIANS HUNGERED FOR WHAT? LITERATURE, MATERIAL CULTURE, AND OTHER HISTORIES Kátia Maria Paim Pozzer1 Abstract The analyzes of the symbolic meaning of food, the culinary habits and the behavior at the table were stimulated by the New Cultural History and favored the studies on the relations between food, culture and social structure. Thus, in this article we intend to discuss the Mesopotamian banquet, its sacred roots, the myths of food creation, the material culture and the rich iconography on the subject. Keywords Mesopotamia; food; material culture; literature. Resumo As análises sobre a significação simbólica dos alimentos, os hábitos culinários e o comportamento à mesa foram impulsionadas pela Nova História Cultural e favoreceram os estudos sobre as relações entre alimentação, cultura e estrutura social. Assim, neste artigo pretendemos discutir o banquete mesopotâmico, suas raízes sagradas, os mitos de criação dos alimentos, a cultura material e a rica iconografia existente sobre o tema. Palavras-chave Mesopotâmia; alimentação; cultura material; literatura. 1 Assistant Professor, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil. E- mail: [email protected] Heródoto, Unifesp, Guarulhos, v. 2, n. 2, Dezembro, 2017. p. 153-167 - 153 - Participate in an academic homage to Prof. Pedro Paulo de Abreu Funari is a privilege because it means that at some point in my professional life I met Pedro Paulo (as he is affectionately called) and I was able to share his wisdom and generosity. Undoubtedly, Prof. Funari is one of the Brazilian exponents of History and Archeology, with greater insertion and international recognition. -

Part 6: Old Testament Chronology, Continued

1177 Part 6: Old Testament Chronology, continued. Part 6C: EXTRA-BIBLICAL PRE-FLOOD & POST-FLOOD CHRONOLOGIES. Chapter 1: The Chronology of the Sumerian & Babylonian King Lists. a] The Post-Flood King Lists 1, 2, 3, & 4. b] The Pre-Flood King Lists 1, 2, & 3. Chapter 2: The Egyptian Chronology of Manetho. a] General Introduction. b] Manetho’s pre-flood times before Dynasty 1. c] Manetho’s post-flood times in Dynasties 1-3. d] Post-flood times in Manetho’s Dynasties 4-26. Chapter 3: Issues with some other Egyptian chronologies. a] The Appollodorus or Pseudo-Appollodorus King List. b] Inscriptions on Egyptian Monuments. c] Summary of issues with Egyptian Chronologies & its ramifications for the SCREWY Chronology’s understanding of the Sothic Cycle. d] A Story of Two Rival Sothic Cycles: The PRECISE Chronology & the SCREWY Chronology, both laying claim to the Sothic Cycle’s anchor points. e] Tutimaeus - The Pharaoh of the Exodus on the PRECISE Chronology. Chapter 4: The PRECISE Chronology verses the SCREWY Chronology: Hazor. Chapter 5: Conclusion. 1178 (Part 6C) CHAPTER 1 The Chronology of the Sumerian & Babylonian King Lists. a] The Post-Flood King Lists 1, 2, 3, & 4. b] The Pre-Flood King Lists 1, 2, & 3. (Part 6C, Chapter 1) The Chronology of the Sumerian & Babylonian King List: a] The Post-Flood King Lists 1, 2, 3, & 4. An antecedent question: Are we on the same page: When do the first men appear in the fossil record? The three rival dating forms of the Sumerian King List. (Part 6C, Chapter 1) section a], subsection i]: An antecedent question: Are we on the same page: When do the first men appear in the fossil record? An antecedent question is, Why do I regard the flood dates for Sumerian and Babylonian King Lists (and later in Part 6C, Chapter 2, the Egyptian King List) as credible, or potentially credible? The answer relates to my understanding of when man first appears in the fossil record vis-à-vis the dates found in a critical usage of these records for a Noah’s Flood date of c. -

Sumero-Babylonian King Lists and Date Lists A

XI Sumero-Babylonian King Lists and Date Lists A. R. GEORGE The Antediluvian King List The antediluvian king list is an Old Babylonian (b) a tablet from Nippur, now in Istanbul text, composed in Sumerian, that purports to (Kraus 1952: 31) document the reigns of successive kings of (c) another reportedly from Khafaje (Tutub), remote antiquity, from the time when the gods now in Berkeley, California (Finkelstein first transmitted to mankind the institution of 1963: 40) kingship until the interruption of human histo- (d) a further tablet now in the Karpeles Manu- ry by the great Flood. The list exists in several script Library, Santa Barbara, California, versions. Sometimes it appears as the opening given below in a preliminary transliteration section of the Sumerian King List, as in text (No. 97) No. 98 below. More often it occurs as an inde- (e) a small fragment from Nippur now in Phil- pendent list, of which one example is held by adelphia that bears lines from the list fol- the Schøyen collection, published here as text lowed by other text (Peterson 2008). No. 96. Other examples of the Old Babylonian A more extensive treatment of the lists of ante- list of antediluvian kings copied independently diluvian kings, including No. 96 and the tablet of the Sumerian King List are: in the Karpeles Manuscript Library, is promised (a) the tablet W-B 62, of uncertain prove- by Gianni Marchesi as part of his forthcoming nance and now in the Ashmolean Museum larger study of the Sumerian king lists. (Langdon 1923 pl. 6) No. -

ANE Deities Compared Genesis 1-11 the Babylonians and Akkadians Adopted the Sumerian Pantheon with Little Changes

ANE Deities Compared Genesis 1-11 The Babylonians and Akkadians adopted the Sumerian pantheon with little changes. Gods were often renamed but their role and status in the pantheon generally remained the same. The dominance of Babylon, however, also led to the ascendancy of the god of Babylon: Marduk assumed power over An, Enlil, and Enki. Sumerian Aspect of Deity Babylonian/Akkadian An God of the heavens Anu Enlil God of the earth and air Enlil / Ellil Enki God of water; Ea god of wisdom and magic Ninhursag (Nimmah, Nintu, Ki) Mother-goddess Aruru Nanna-Sin Moon god Sin Utu Sun God; Shamash god of justice Ereshkigal Goddess of the underworld Nergal Ishkur Storm god Marduk (Adad, Ashur, Bel) Abzu Primordial sweet-water ocean Apsu (Enki’s abode) Nanshe The salt-water ocean Tiamat1 Dumuzi God of vegetation; god of the Tammuz underworld; shepherd god Inanna Fertility goddess; Ishtar goddess of love and war Ashnan God of grain Dagan Nidaba, Nisaba God of scribes, literacy, Nabu and wisdom Anunnaki2 Lesser gods, workers Anunnaki, Igigi2 Blue = the supreme gods (highest of the seven primary gods) Red = additional members of the seven primary gods Green = other important gods 1 Enuma Elish tells the story of Marduk’s victory over the sea monster Tiamat. 2 Anunnaki and Igigi are both collective terms for a group of otherwise nameless gods. It is uncertain whether or not they stand for the same group of gods. The Anunnaki seem to hold a higher position. Chart inspired by G. Herbert Livingston, The Pentateuch and Its Cultural Environment (pp. -

In Search of the Historical Adam: Part 2

In Search of the Historical Adam: Part 2 Dick Fischer P. O. Box 50111, Arlington, VA 22205 From PSCF 46 (March 1994): 47. In this article, the second in a series of two, the culture that surrounded the early Adamites in Southern Mesopotamia starting about 5000 to 4000 BC is examined. Early cuneiform writings and inscriptions speak about an historical figure that could have been Adam of Genesis. The Sumerian king lists of early pre-flood rulers begin with "Alulim," the probable equivalent of Adam. Eridu, the oldest city in Southern Mesopotamia, dating to about 4800 BC, is the most likely place to have been Eden, the original home for Adam and his kin. Even the word "Eden" apparently was derived from the Sumerian "edin," meaning "plain," "prairie," or "desert." "Enoch," the city Cain built in the pre-flood period corresponds with "Eanna(k)," a Sumerian and Semite post-flood site. Thus the early passages of Genesis are seen as factually relevant, and an integral part of secular pre-history. Cuneiform inscribed clay tablets discovered in Mesopotamian excavations have given archaeologists a picture of a civilization almost totally unknown only one hundred years ago .1 These have given us valuable insights into the history, religion, and racial diversity in the region. And some of these tablets contain references that may appear to pertain to Adam of the Bible. The Legend of Adapa Related to Adam Several fragments of the "Legend of Adapa" were taken from the Library of Ashurbanipal (668-626 BC) at Ninevah. One was also found in the Egyptian archives of Amenophis III and IV of the fourteenth century BC.